Antarctica Was Once Covered in Forests. We Just Found One That Fossilized.

The ancient trees were able to withstand alternating months of pure sunlight and darkness, before falling in history's greatest mass extinction.

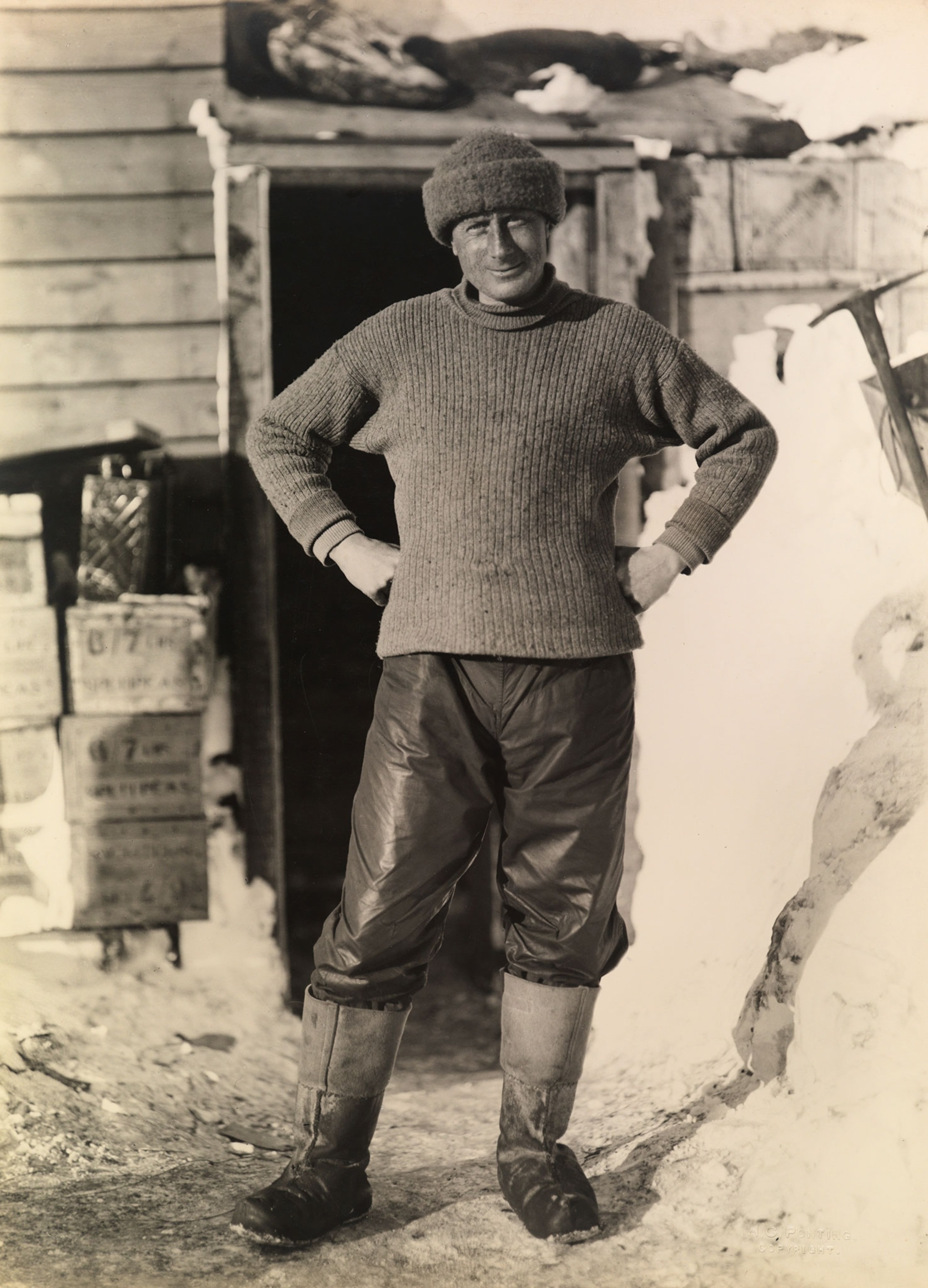

It was summer in Antarctica, and Erik Gulbranson and John Isbell were on the hunt.

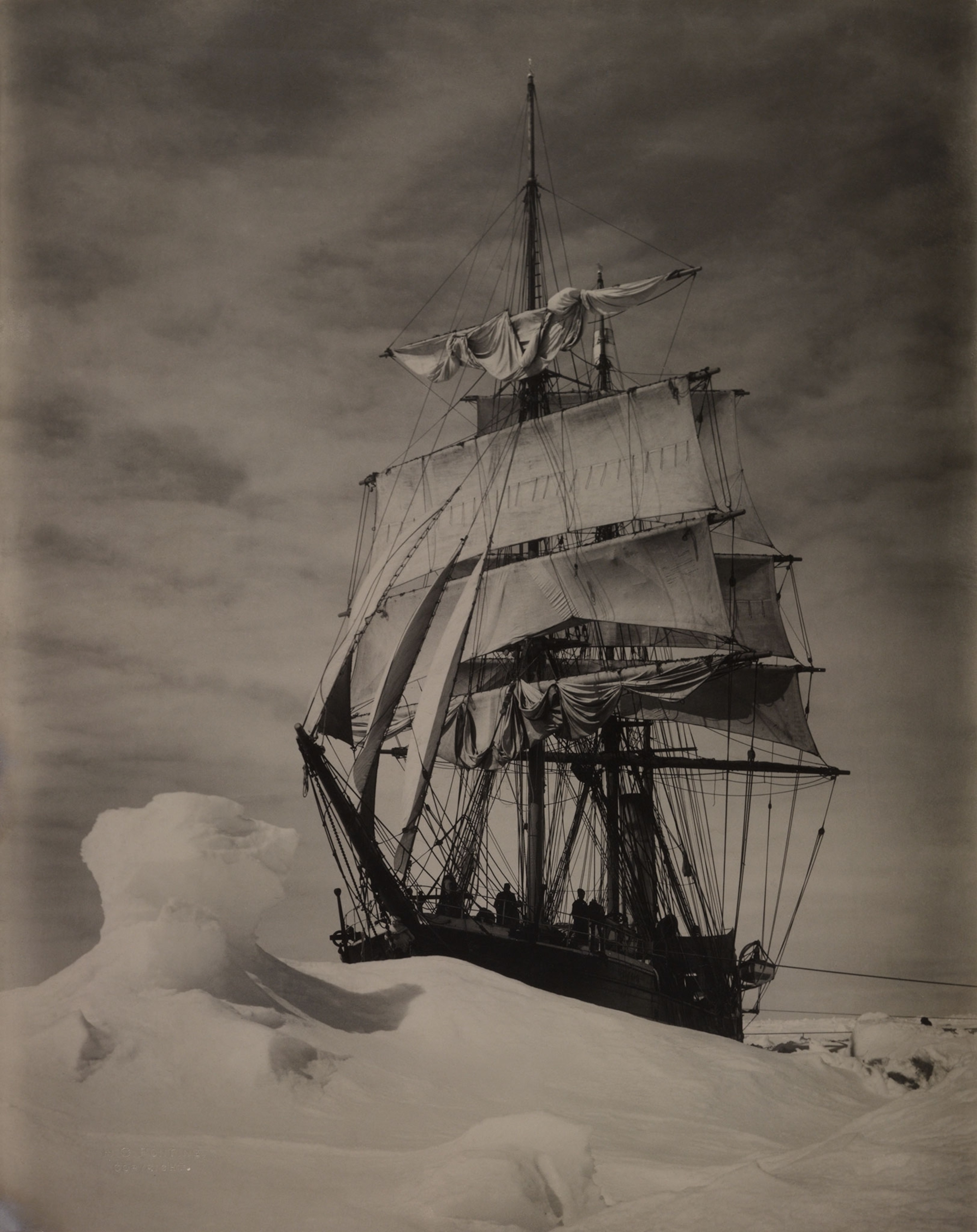

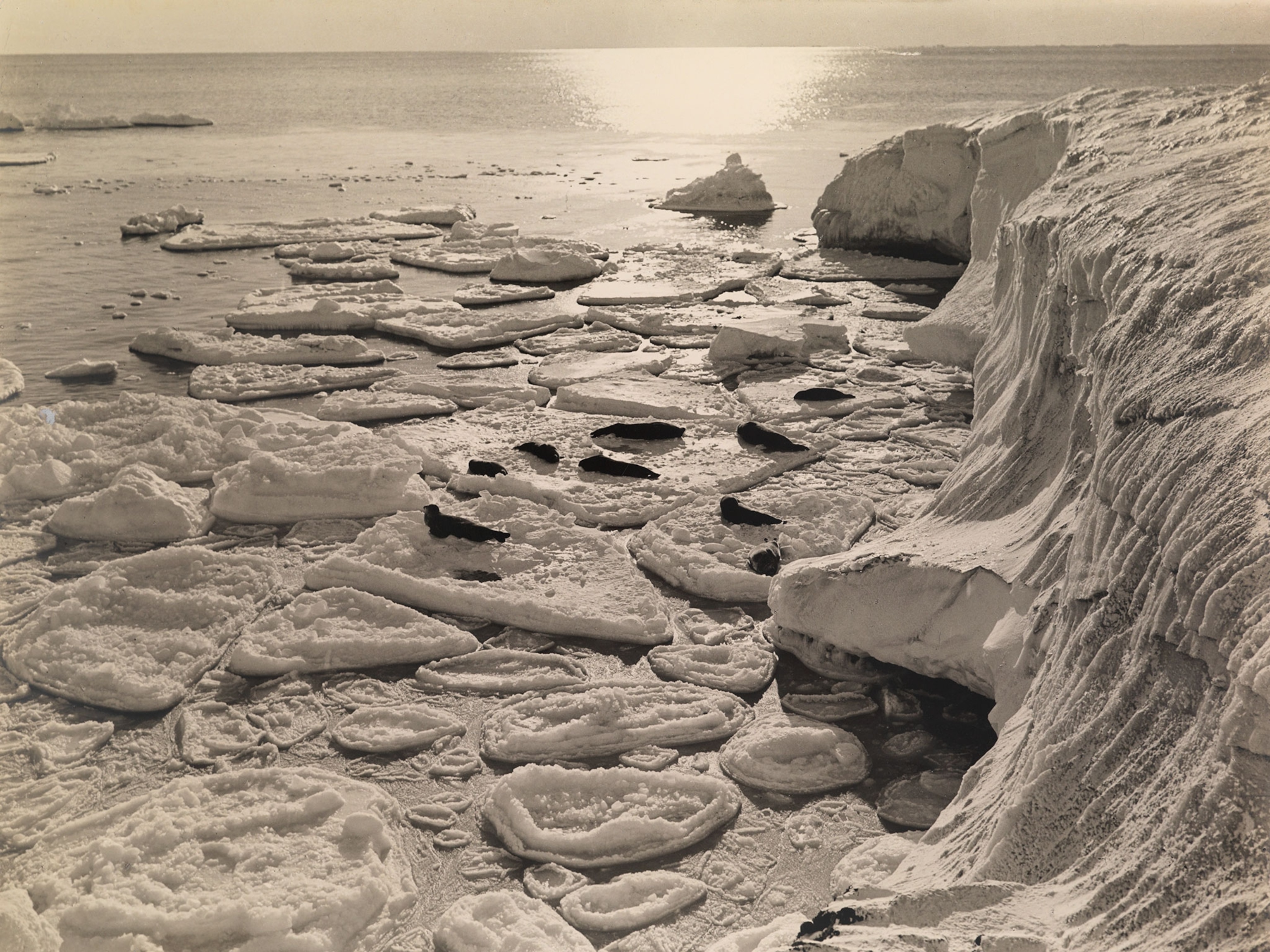

Bundled up in parkas to brave negative temperatures, fierce winds, and blinding days of 24-hour sunlight, Gulbranson, Isbell, and an international team of researchers searched for fossil fragments. Between November 2016 and January 2017, they scaled the snow-capped slopes of the McIntyre Promontory high above the ice fields and glaciers, sifting through the Transantarctic Mountain's gray sedimentary rocks for clues. By the end of the expedition, they had uncovered 13 fossil fragments from trees dating back more than 260 million years, around the time of the world's greatest mass extinction event.

The fossil discovery hints at the coldest, driest continent's green and forested past. (Read more about a green snap in Antarctica's history.)

A Green History

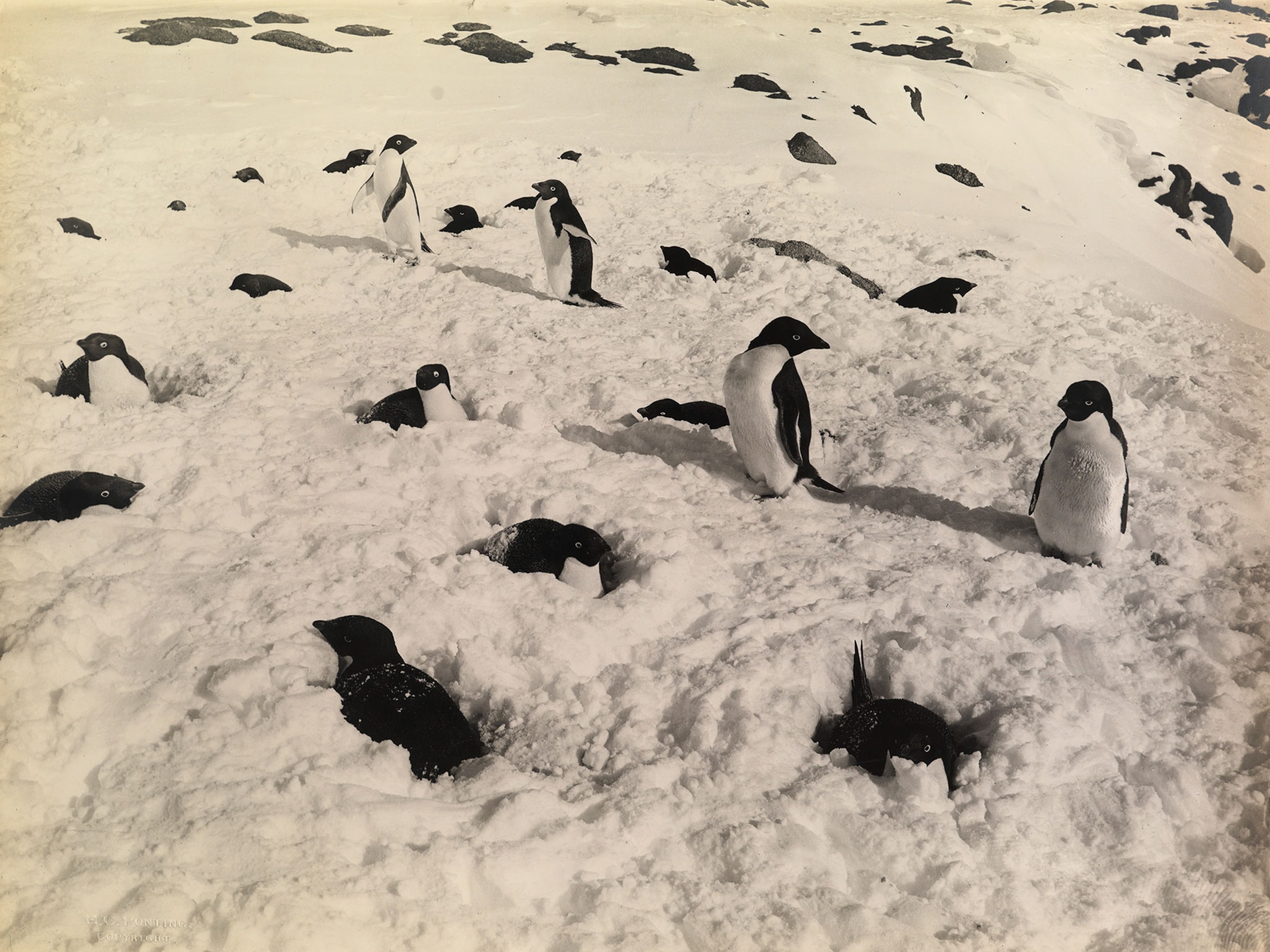

"The continent as a whole was much warmer and more humid than it currently is today," says Gulbranson, a professor at University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. The landscape would have been densely forested with a low-diversity network of resilient plants that could withstand polar extremes, like the boreal forest in present-day Siberia.

"Oddly enough, these field sites would have actually been very close to what their current latitude is," he adds.

The fossils preserved the biology and chemistry of the ancient trees, which will help the researchers investigate more on these high-latitude ecosystems to figure out how some plants survived the extinction event, and why others didn't. What's more, fossil microorganisms and fungi have been preserved inside the wood.

The specimens look similar to the petrified forests in Yellowstone National Park, which were fossilized when volcanic materials buried the living trees.

"They're actually some of the best-preserved fossil plants in the world," Gulbranson says. "The fungi in the wood itself were probably mineralized and turned into stone within a matter of weeks, in some cases probably while the tree was still alive. These things happened incredibly rapidly. You could have witnessed it firsthand if you were there."

The researchers found the prehistoric plants could transition rapidly between seasons, perhaps within the span of a month. Whereas modern plants take months to transition and conserve water differently depending on the time of day, the ancient trees could fluctuate quickly between pitch black winters and perpetually sunny summers.

"Somehow these plants were able to survive not only four to five months of complete darkness, but also four to five months of continuous light," Gulbranson says. "We don't fully understand how they were able to cope with these conditions, just that they did."

Mass Extinction

The Permian period, dating between 299 to 251 million years ago, is marked by the emergence of the supercontinent Gondwana. As a mash of continents, environmental extremes plagued the giant land mass, which included parts of modern-day Antarctica, South America, Africa, India, Australia, and the Arabian Peninsula. Ice caps dominated most of the south and tossed it between ceaselessly sunny summers and pitch-black winters, while the north suffered intense heat and seasonal fluctuations.

Prehistoric creatures learned to adapt to the turbulent climate until the Permian extinction, which Gulbranson says was most likely caused by volcanism in present-day Siberia. The event wiped out more than 90 percent of marine species and 70 percent of land animals, later making the way for dinosaurs.

Looking Forward

The team is planning to continue research in Antarctica by revisiting the continent in the coming weeks. John Isbell and other researchers are already making their way down, and Gulbranson will join them at the polar locale November 23.

"It's certainly still a raw and challenging place to try to be as a human being," Gulbranson says.