National Parks Were America’s Best Idea. Let’s Bring Them Underwater

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument is now the world’s largest marine protected area. We can do more.

One hundred years ago, President Woodrow Wilson and Congress created the National Park Service to conserve areas of natural, cultural and historic importance and leave them “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

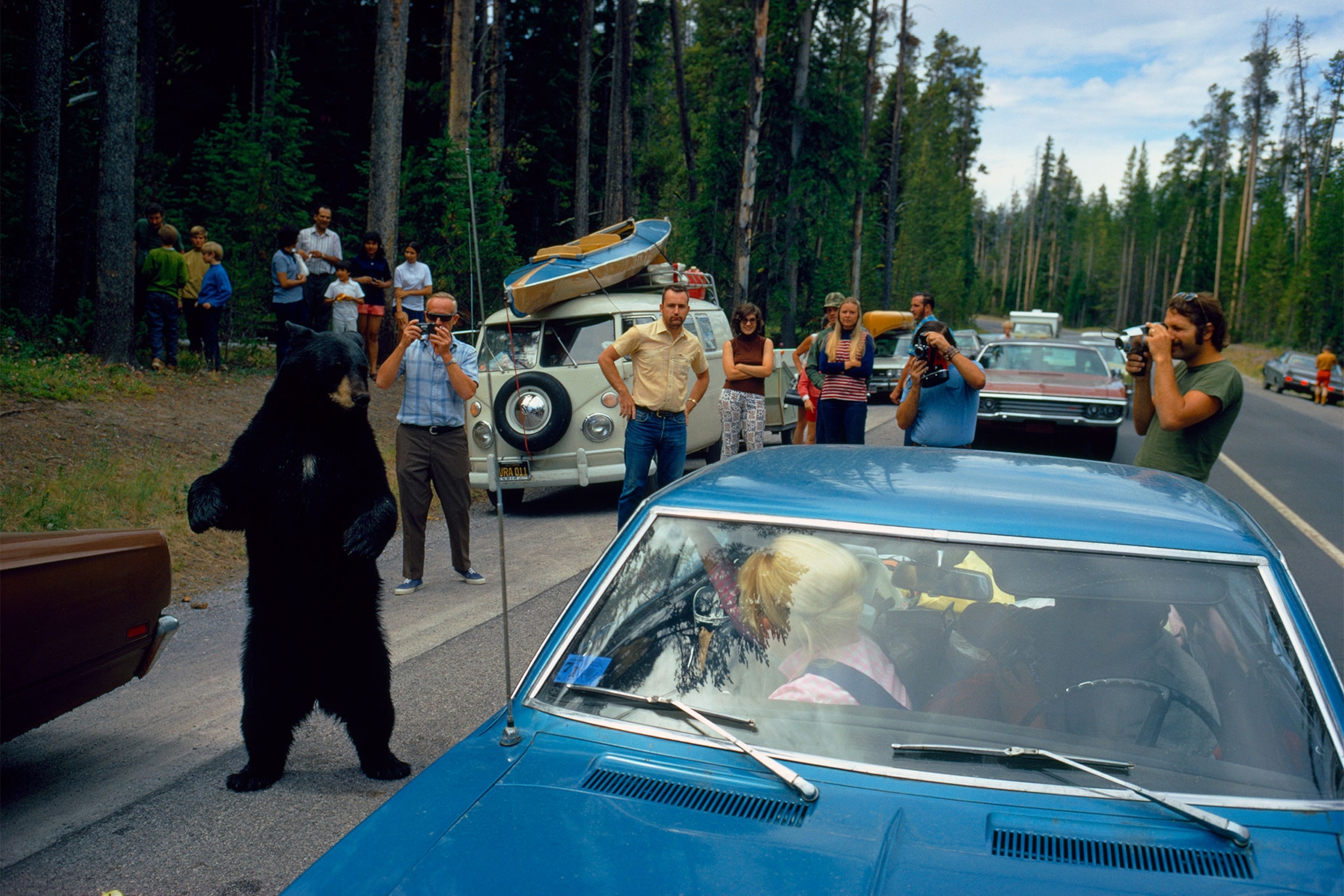

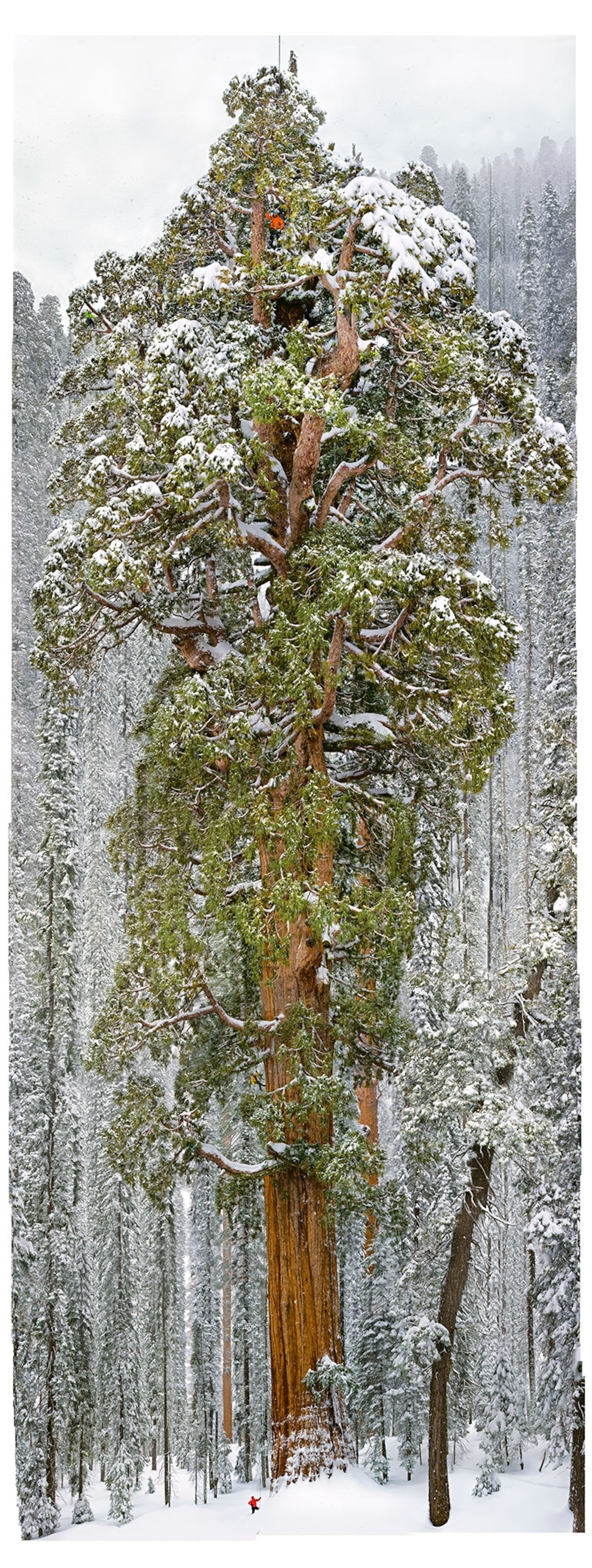

Places like Yellowstone and Yosemite were already in federal protection, but in the next 100 years, America’s “best idea” would include 413 areas and more than 84 million acres of vast wilderness, scenic rivers, military battlefields, presidential homes and more. It was a radical idea to put large tracts of land into federal custody on the heels of the Industrial Age when almost nothing was untouched by development and our manifest destiny.

Americans on this centennial anniversary are encouraged to “find your park” and enjoy these wonders that are the collective conscious of our nation. But with President Obama’s expansion of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument from 50 to 200 miles out from the Northern Hawaiian Islands, now the world’s largest marine protected area, history will remember this anniversary and next century as the “blue centennial”—the time when the national park idea was brought to the ocean. It couldn’t come too soon.

A century ago, we knew very little about the ocean, but today we know how important it is to planetary chemistry, regulating temperature, governing climate and weather, generating most of the oxygen in the sea and atmosphere, powering the carbon, nitrogen and water cycles, holding 97 percent of both the Earth’s water and biosphere, and harboring millions of species. Without a healthy ocean, we will not have a habitable planet.

The challenge ahead is daunting. Since the 1950s, human beings have been so efficient with their extraction technologies that 90 percent of many fish—tunas, swordfish, marlin, sharks, cod, and halibut—and other ocean wildlife have been plucked as commodities. Half of the coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows and much of the phytoplankton have disappeared or are in serious decline.

On ocean expeditions, we now run into fishermen who plead for permanent safe havens where fish and the ecosystems that support them can recover. Oceans also are the repositories of our wastes, creating dead zones that have approximately doubled in size every ten years since the 1960s. Ocean acidification, driven by excess atmospheric carbon dioxide, is altering ocean chemistry. The ocean is certainly not too big to fail.

There is still time to act if we make the next decade and century count for the ocean and wildlife within it. Scientists tell us at least 30 to 50 percent of the ocean must be fully protected to restore its health. Today, only about 2 percent of the ocean is protected from destructive activities including industrial-scale fishing and mining, while the land has received seven times that amount of protection.

Bipartisan progress has been made in the U.S., but we must aggressively build on it here and around the world. In his second term, President George W. Bush created the world’s largest marine protected area in the Pacific with Papahānaumokuākea, Marianas Trench, Pacific Remote Islands, and Rose Atoll national monuments. Mrs. Laura Bush hoped they would unleash a “new wave of parks” around the world.

Just in the last few years, Britain created Pitcairn Island Marine Reserve, the island nation of Palau protected 80 percent of its waters, and New Zealand and Chile have created large marine parks. President Obama has now raised the ocean stakes by taking protection to the borders of our exclusive economic zone around the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

Now let’s finish the job. In New England, a cape was named after the cod that were so plentiful a century ago and are now absent. Cod are still found in places such as Cashes Ledge, and pristine areas including Seamounts and Canyons 150 miles off the coast that should become permanently protected marine reserves.

In the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and decades of mining and agricultural wastes dumped into the Gulf of Mexico, can’t we at least protect Ewing Bank and other areas to help the Gulf recover? Critically important areas off California and Alaska deserve full protection. Resources for management and enforcement must be provided, and the High Seas, the blue heart of the planet, is a largely unregulated global commons ripe for international protection to safeguard planetary resilience and basic life support.

From 1872 when the first national park called Yellowstone (named after a mighty river) was created to the present day, there have been naysayers to oppose the creation of national parks and monuments. But Americans took the longer view and protected our natural, historic and cultural resources for future generations.

As we listened to Hawaiians in a public hearing on Oahu appeal to their leaders to expand what is now the largest marine protected area in the United States and world, we heard one of the most respected Hawaiians say, “with this expansion, we’ll be bold in conserving our resources and cultural heritage for future generations; let the rest of America and world now be bold.”

He is right. Let’s make this century the Blue Centennial.

Dr. Sylvia Earle is an oceanographer, National Geographic Society explorer in residence, author, and former Chief Scientist of NOAA. She is featured in the Emmy Award winning documentary film, Mission Blue, released on Netflix in 46 countries. John Bridgeland was former Director of the White House Domestic Policy Council, member of the National Park System Advisory Board, and co-leader of the cabinet-level review of climate change in 2001. Both are part of the forthcoming NGS Blue Centennial film produced by Bob and Sarah Nixon.