See the Last Pictures From the Cassini Mission to Saturn

As the beloved spacecraft hurtled toward its fiery doom, it beamed home a final collection of eerily beautiful images.

Before its fatal rendezvous with Saturn’s flaxen clouds early Friday morning, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft delivered one last set of postcards from the planet’s edge.

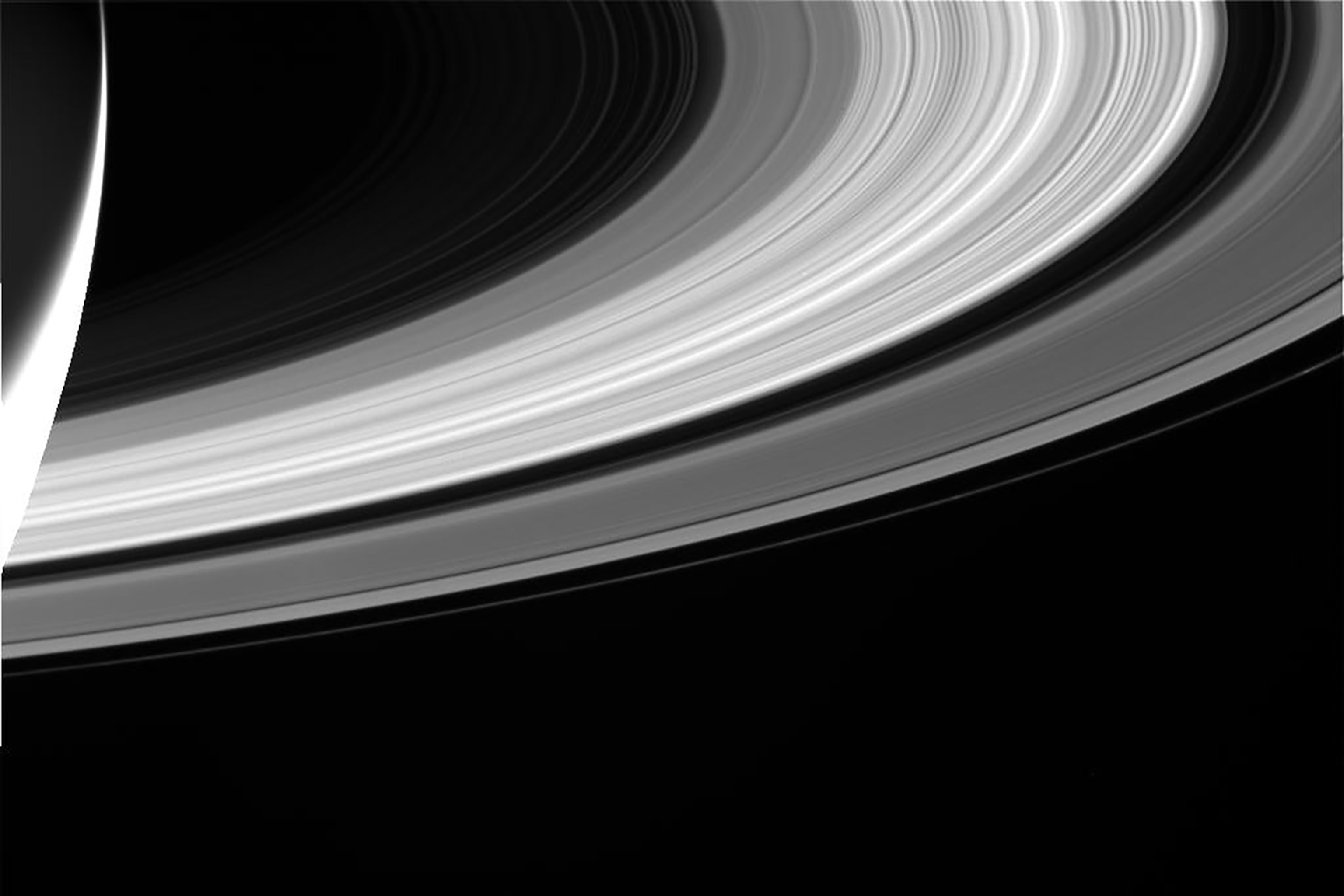

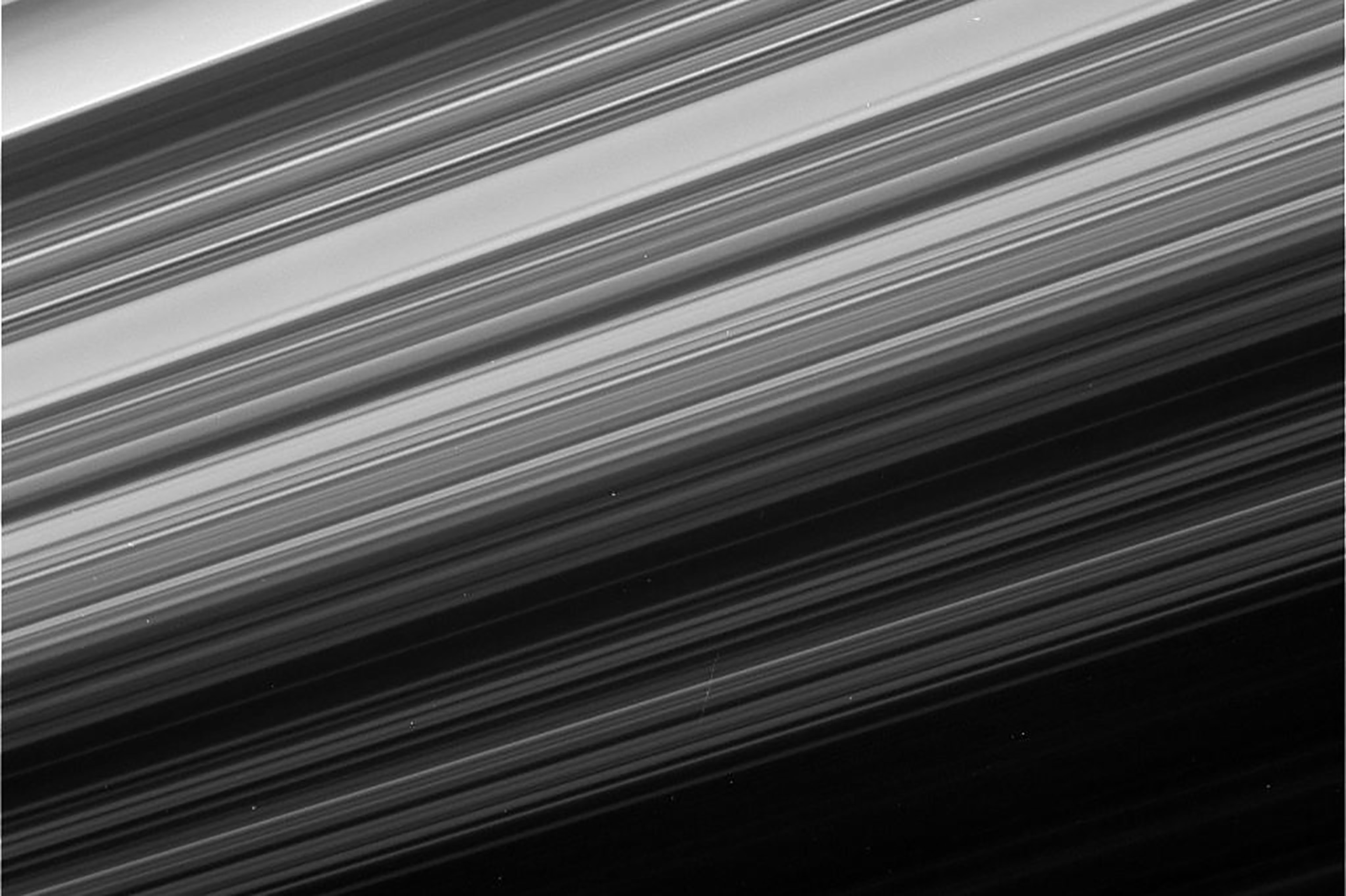

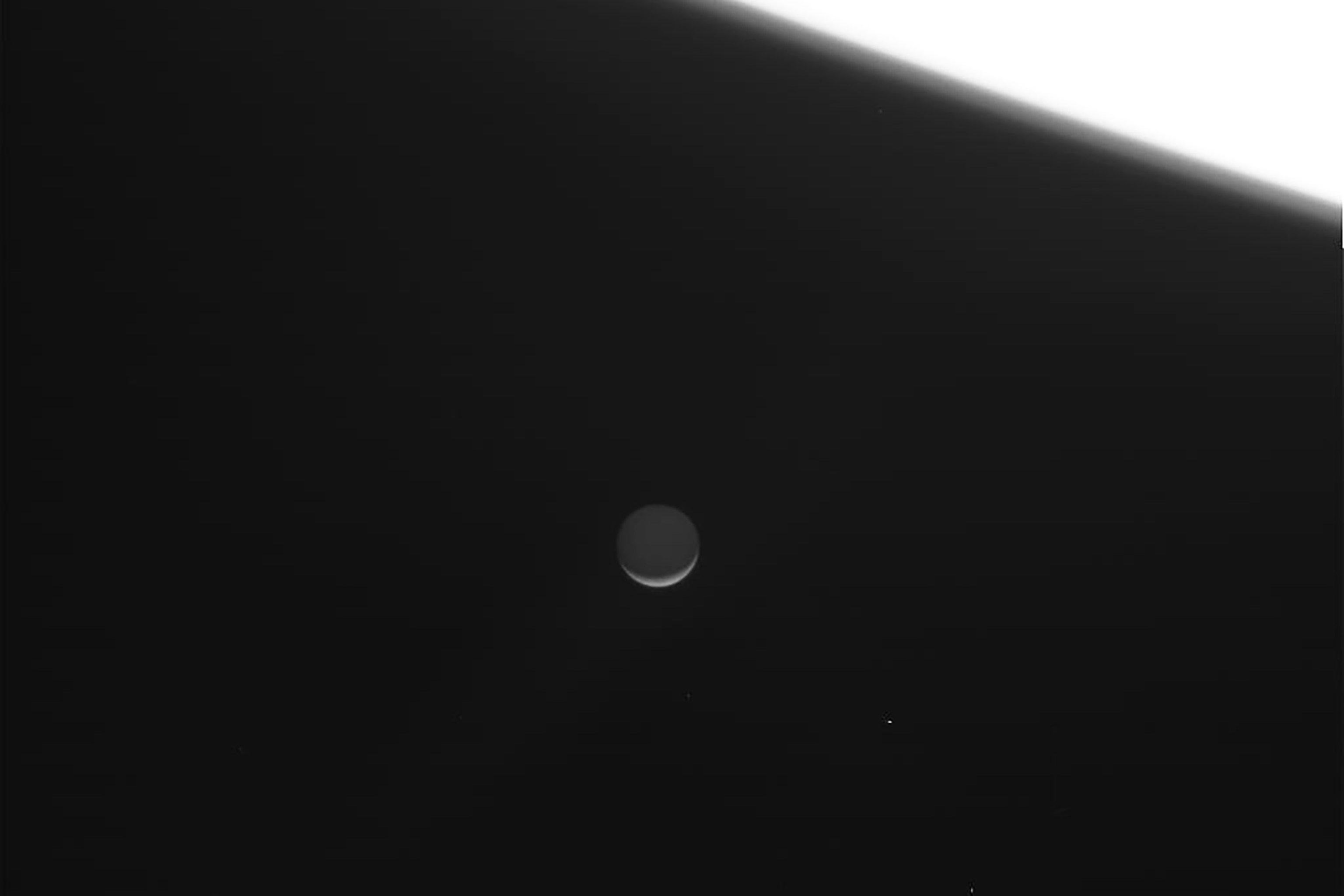

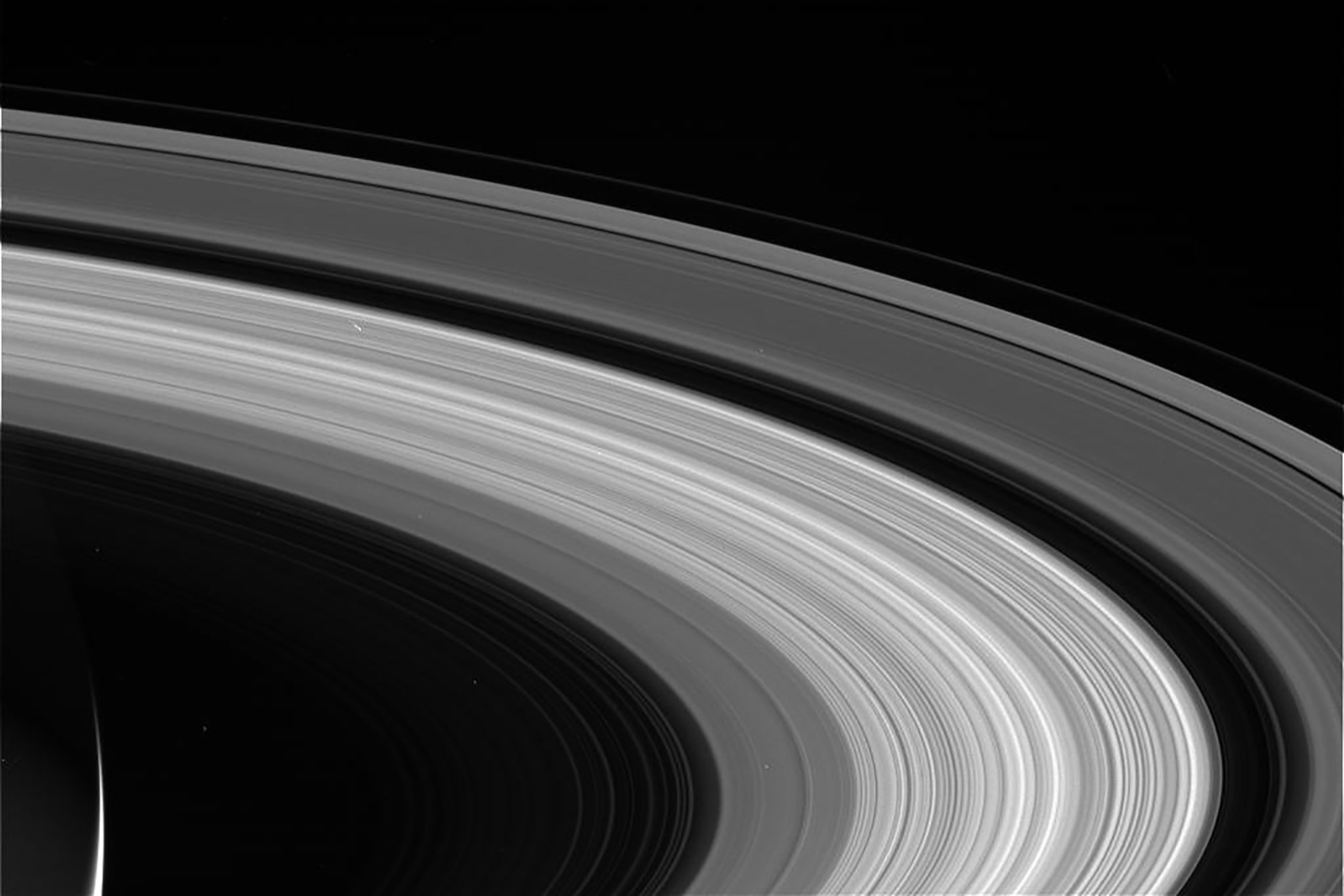

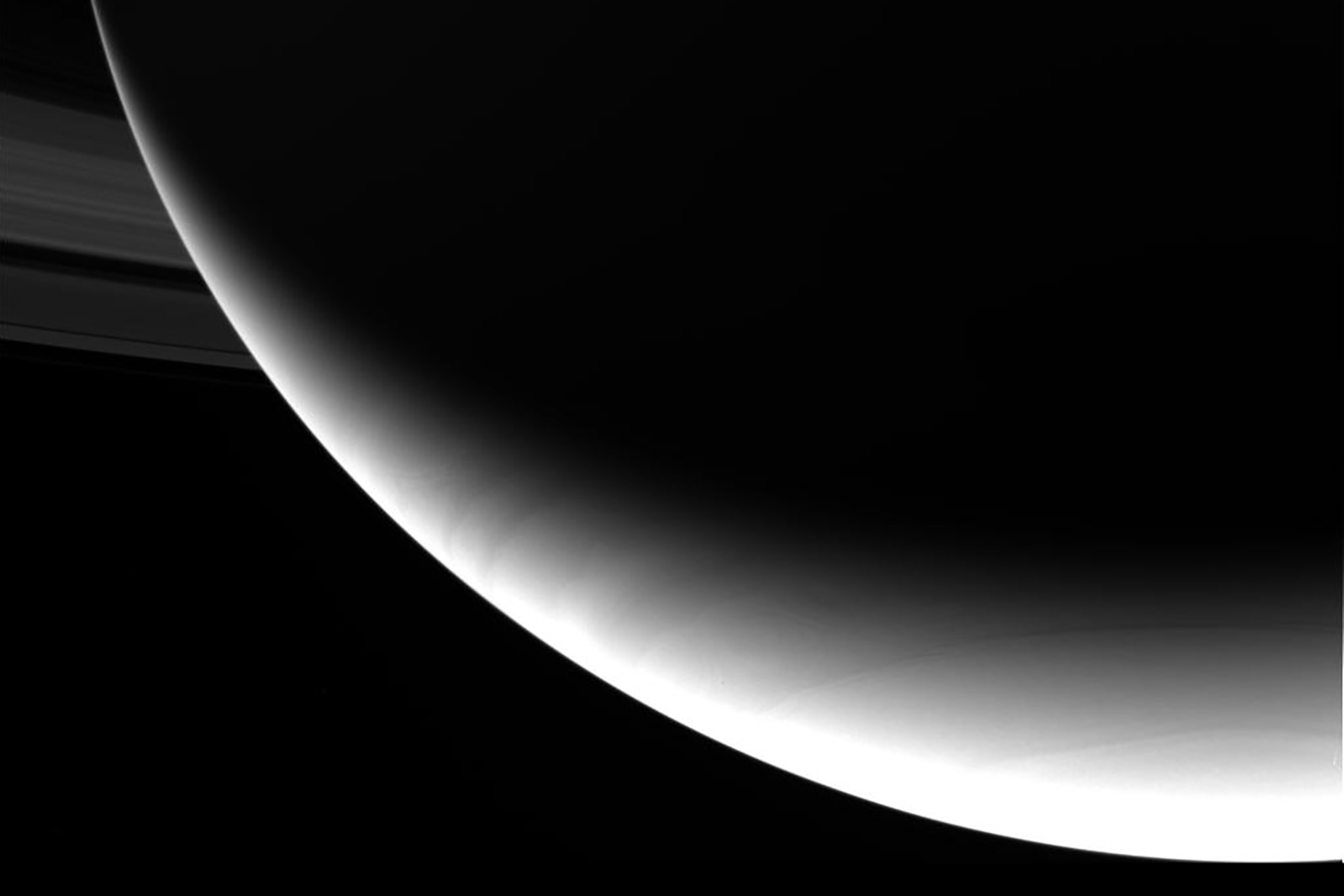

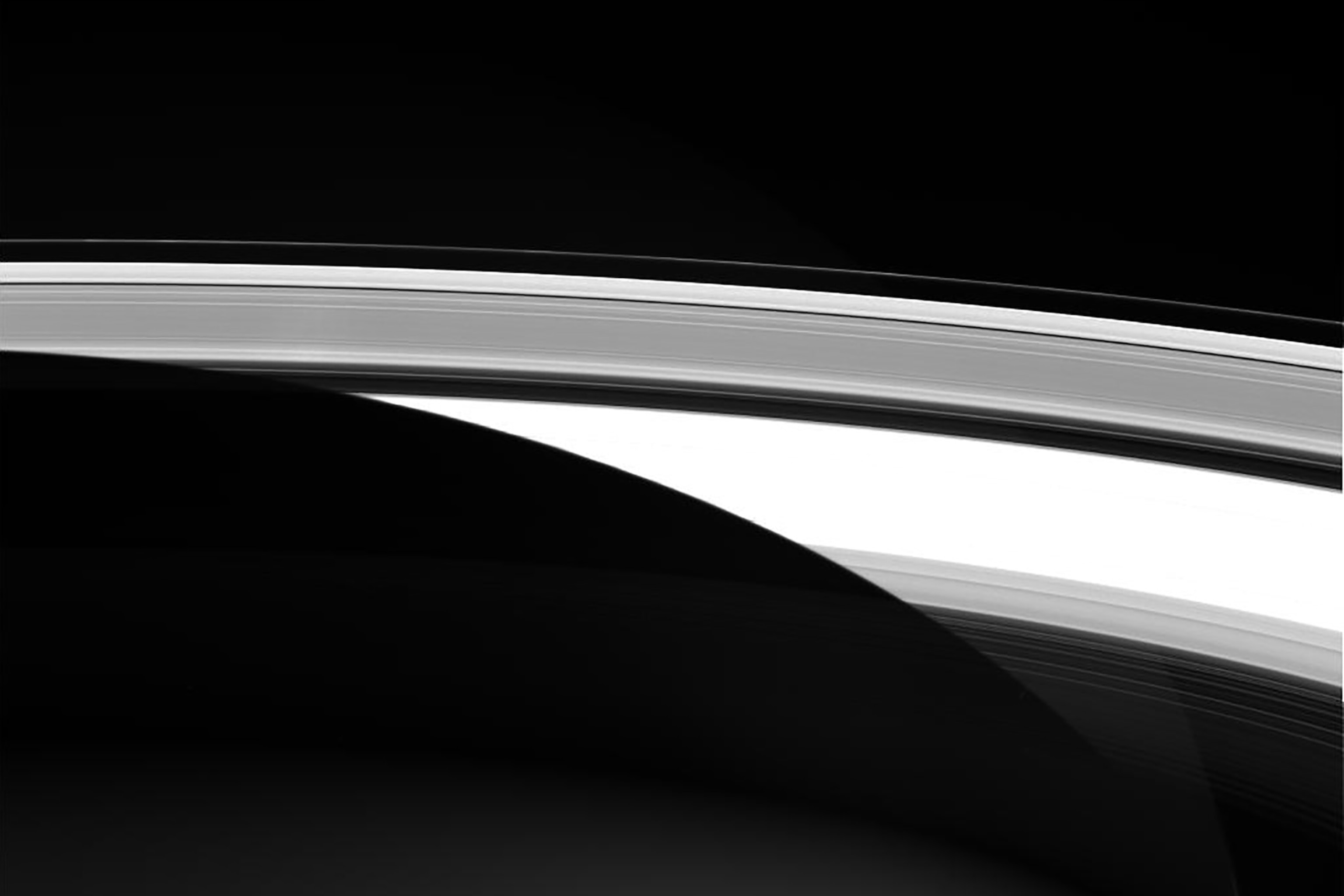

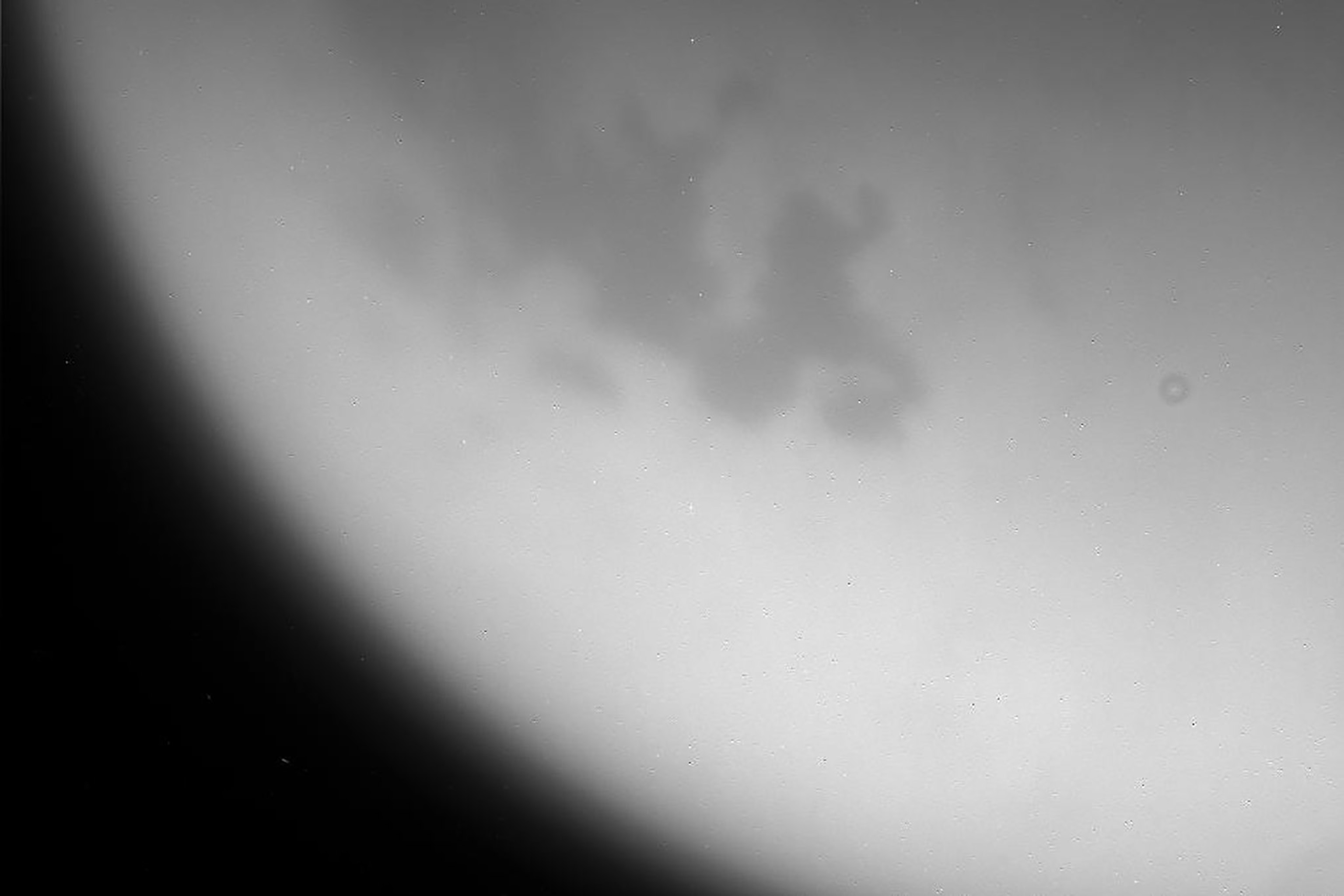

It’s a little bit like a farewell collage: In these raw, unprocessed images, the hazy moon Titan gleams, the ice moon Enceladus creates a cosmic grin, the giant planet shines, and its iconic rings fill the spacecraft's field of view.

As new images stream back to Earth over the next few hours, mission managers expect to also see a small moonlet nicknamed Peggy gliding among the planet's enormous A ring.

“We’ve been watching since 2012 to see if Peggy might break free of the rings and become a moon in her own right,” says Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker. “So we’re going to take a last look, see what Peggy is up to.”

It’s easy to understand why the team chose these final targets. They are among the most evocative and puzzling members of the Saturn system, which Cassini has spent the last 13 years exploring. Over that time, it has snapped nearly half a million pictures.

And now, with just a few short hours remaining before heat and pressure tear Cassini apart at approximately 4:55 a.m. PT, it makes sense to visit some of its old friends for the last time.

“We’re taking our final picture postcards of the Saturn system, looking at our favorite targets, to put these images in our Cassini scrap book,” Spilker says. NASA is expected to release more refined, processed versions of these pictures on Friday morning.

Titan, shrouded in a thick tangerine haze, is bigger than the planet Mercury. Its surface is covered with oily lakes and seas that had only been hypotheticals until Cassini arrived and peeled back the cloudy shroud concealing the moon’s eerily Earth-like surface.

Now, thanks to the spacecraft’s close examinations, we know that Titan is among the best places to look for life in the solar system.

“I suspect this parting image, seared permanently into our memories, will carry many of us through long meetings and sleepless nights until our next robotic explorer is safely on its way back to Titan,” Johns Hopkins University’s Sarah Hörst says of Cassini’s farewell glance at the enticing moon.

The same is true of Saturn’s smaller, icy moon Enceladus. When Cassini zipped by that moon in 2005, it spotted geysers of saltwater erupting from the south pole. Though there had been long-ago predictions of such activity, no one was prepared for just how spectacular the frosty fountains can be.

In the intervening years, Cassini revealed that a global sea sloshes beneath Enceladus’s icy rind, and it contains all the ingredients necessary for life as we know it.

Or, perhaps, as we don’t know it.

It’s because of these two moons that Cassini cannot be left at large in the Saturn system. Its fuel reserves are low, and scientists don’t want to risk contaminating one of these two potentially life-bearing worlds.

“An uncontrolled spacecraft either had to be well outside of Saturn—way, way outside—or inside,” says Cassini program manager Earl Maize.

So, as Cassini bids farewell to scientists on Earth, it will do so with a final bit of poignancy.

Among its last images will be a view of the site at which it will dip its toes into Saturn’s atmosphere, diving deeper as it gazes toward Earth and delivers data until it streaks into nothingness.