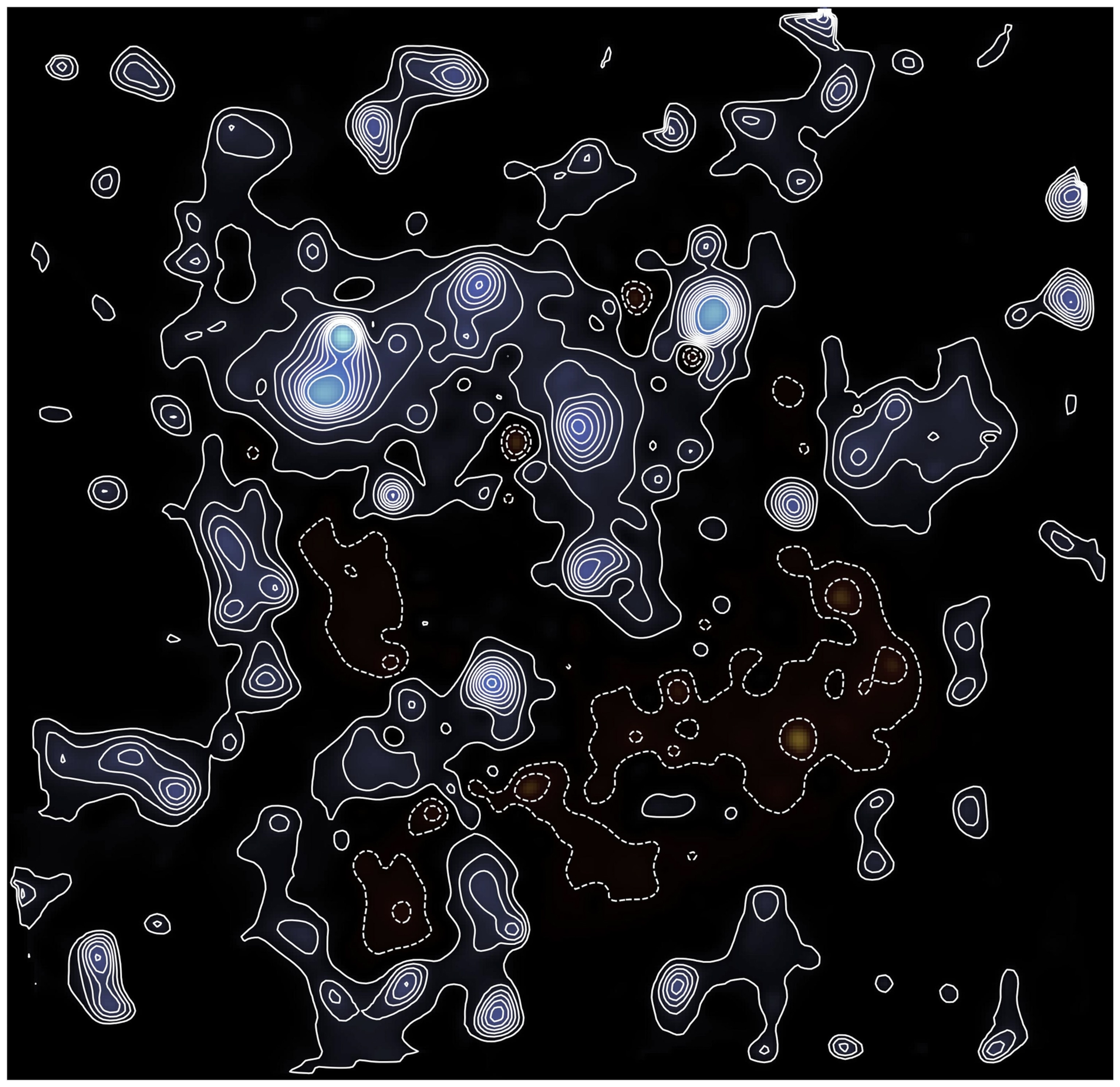

Scientists assemble the most detailed map of dark matter ever

Dark matter is a mysterious substance that glues galaxies together. This map from the James Webb Space Telescope could help scientists finally figure out what it is.

One of the most persistent and important puzzles in all of physics is: What is dark matter?

The invisible and mysterious material is about five times more prevalent in the universe than the ordinary matter that makes up people, animals, planets, stars, and everything humans have ever been able to see. While scientists can’t directly detect dark matter with telescopes, they can detect the influence of its gravity on large scales, like that of galaxies and galaxy clusters.

But to solve the mystery of dark matter, scientists first need to know: Where is it?

While previous efforts have attempted to chart dark matter in various ways across the cosmos, a new study published January 26 in the journal Nature Astronomy provides the highest-resolution map of dark matter to date. The new findings rely on data from the James Webb Space Telescope and reinforce scientists’ current theory that dark matter’s gravity pulled ordinary matter into clumps that grew into the first structures in the universe.

“It's the gravitational scaffolding into which everything else falls and is built into galaxies. And we can actually see that process happening in this map,” says Richard Massey, study co-author and physicist at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

Without dark matter, there wouldn’t be enough matter to gravitationally bind galaxies together, and our Milky Way galaxy, housing billions of planets including Earth, would not exist in its current form.

(Learn more about the scientist who discovered dark matter.)

Mining the COSMOS field

The map represents part of a region of the sky is known as the COSMOS field, which has been well studied by the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories. While the new Webb map contains almost 800,000 galaxies, many of which were previously unknown, its area covers a tiny sliver of sky—about 2.5 times larger than the full moon.

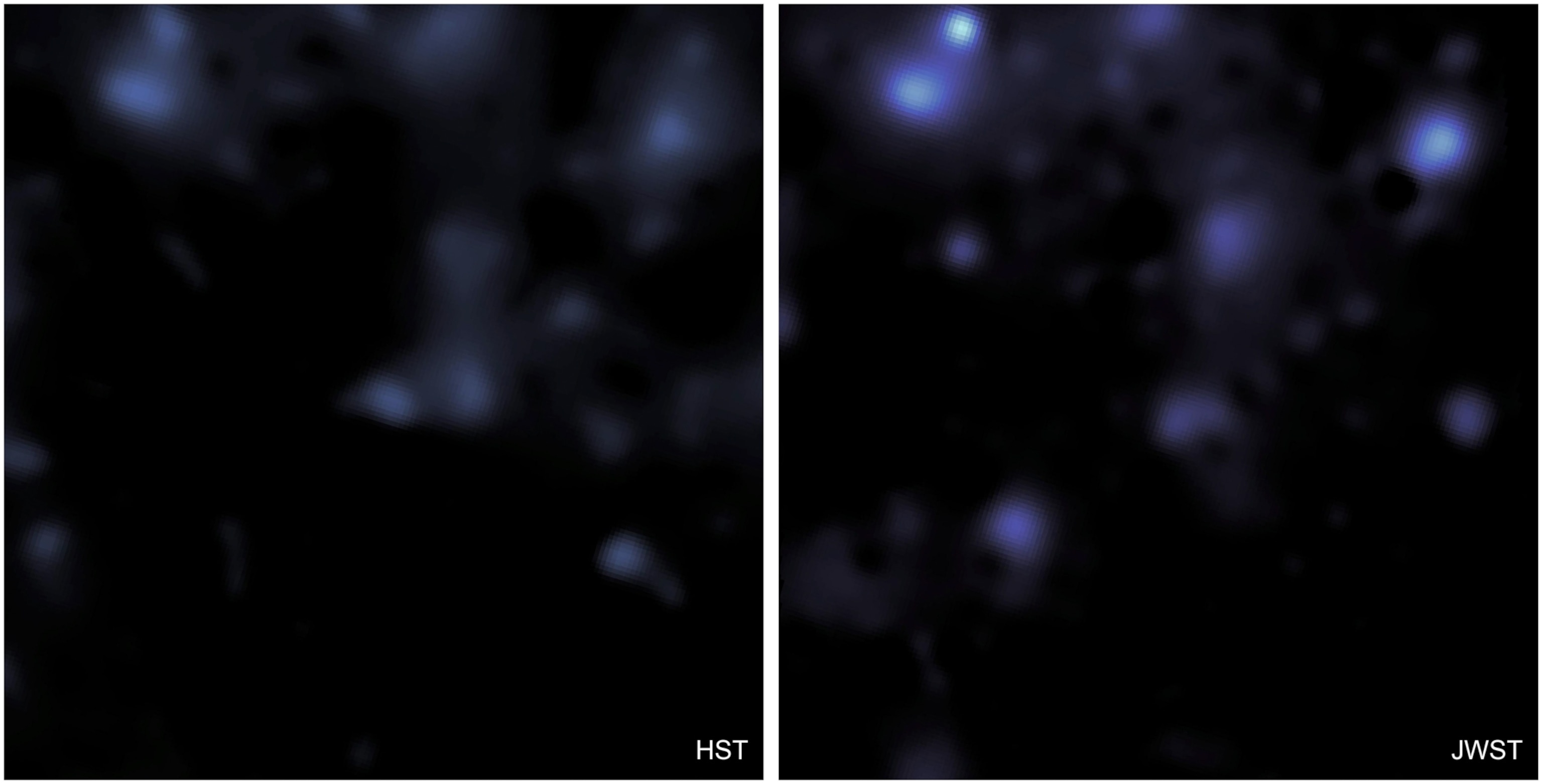

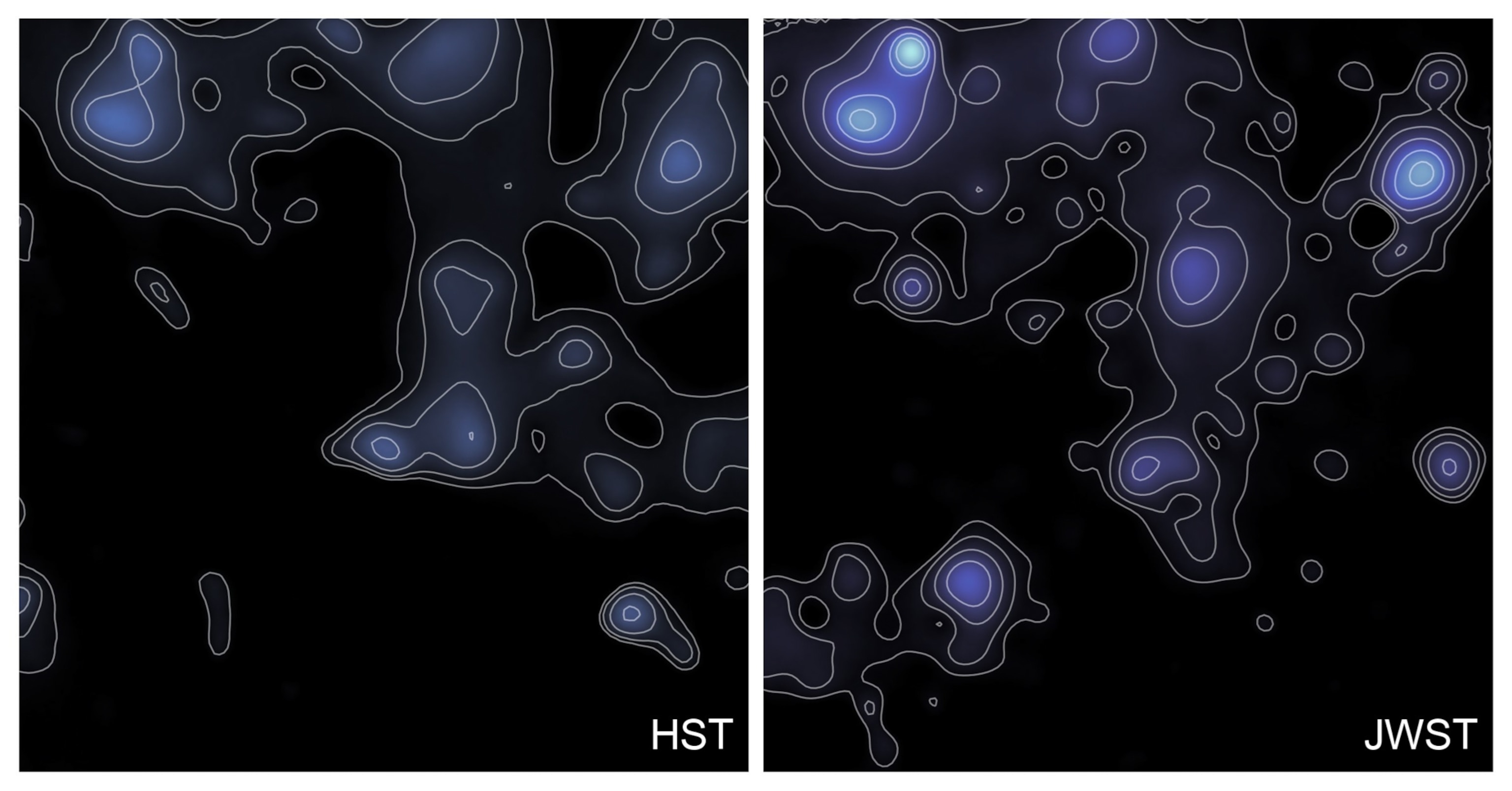

Notably, about 20 years ago, Hubble delivered detailed imaging of the COSMOS field, enabling a look at the universe’s structure that was groundbreaking at that time. Armed with higher resolution data from Webb, scientists can now overlay the new data on top of the old to verify previous analyses and discover new features of the universe’s underpinnings.

“We can see that the structures match each other, but now we can see with much better details and with finer details. So this is stunning,” says Diana Scognamiglio, a cosmology researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led the new study.

Because Webb sees infrared light, it provides views of galaxies that formed billions of years ago in the early universe. This allows scientists to infer the presence of structures of dark matter called filaments, forming “cosmic web” in which galaxies are strung along the invisible threads. “There's galaxies strung out like beads wherever we see dark matter, at all sorts of different distances away from us at different times since the big bang,” Massey says.

Scientists think that after the birth of the universe, dark matter clumped together to form this scaffolding, where ordinary matter then glommed on. The Webb map bolsters this idea. “Wherever there's dark matter, it pulls in the ordinary material and starts to accumulate enough ordinary material in any one place to form stars and planets,” Massey adds.

(Dark matter is a huge mystery. This device is trying to detect it.)

How scientists constructed this dark matter map

To indirectly detect large sources of dark matter across this particular patch of sky, scientists used a technique called gravitational lensing.

A massive cosmic object like a galaxy or galaxy cluster can cause light from a more distant source to bend and appear distorted. In a phenomenon called “strong lensing,” light from the distant source is brightened, such that it appears magnified or even warped around it like a ring. But in this case, researchers were looking for more subtle “weak lensing,” in which galaxy shapes are ever so slightly distorted or displaced because dark matter disrupts the trajectory of light. A large number of galaxies is necessary to calculate the amount of dark matter responsible for the weak lensing effect.

“The galaxies, or whatever we're looking at, get bent into these characteristic shapes, like a funhouse mirror, or like looking through a kitchen a bathroom window,” Massey says. “And we work out how much dark matter there is by figuring out how it distorted the shapes of these background galaxies.”

Measuring dark matter indirectly in this way is akin to observing the trees and inferring that wind causes the movement of leaves and branches, Massey says. That’s no small feat when it comes to calculating subtle changes in hundreds of thousands of galaxies. Researchers looked at the same patch of sky with Webb for 255 hours, representing the biggest survey from the first year of the telescope’s scientific operations, which began in 2022.

More than just this map

The map itself is just the beginning, however. Rachel Mandelbaum, a physicist at Carnegie Mellon University who was not involved in this study, looks forward to future science that comes from the map, which may include analyses of how particular types of galaxies relate to the amount of dark matter in those galaxies, how galaxies are distributed, and better understanding galactic “voids,” regions where there are fewer-than-average galaxies.

Such analyses will “help us answer our basic questions about the universe and how matter is distributed and how galaxies have evolved,” she says.

The Webb dark matter map also comes just as a golden age of exploring the dark universe begins. The European Space Agency’s Euclid telescope, which launched in 2023 and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, expected to launch this fall, will provide complementary observations of dark matter across a much wider swath of sky. Both of these telescopes were designed for large surveys, while Webb homes in on much smaller slices of the sky in greater detail. The new Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which released its first images in June 2025, will additionally provide maps of galaxies and dark matter that will enhance our scientific understanding of this mystery.

The map is “a key first step for all the next future knowledge that we will get on dark matter,” says Gavin Leroy, a researcher at Durham University who co-led the study.

Scientists are now working on a three-dimensional version of the new Webb dark matter map. Combined with the large surveys from other observatories, this will enable scientists to finally home in on the properties of dark matter itself. For example, does dark matter consist of massive, slow-moving particles—what scientists call “cold”—or lighter, faster-moving “warm” particles?

“I hope that the people can see this as a foundation for other study,” Scognamiglio says. “And that we will be able to extend the data with other telescopes and combine them to do cosmology and to really understand what the dark matter is.”