Watch a black hole fall into a star and then blow it up

NASA has visualized the cataclysm, which is thought to have caused a mysterious eruption of gamma rays captured by telescopes earlier this year.

It’s the greatest cosmic murder mystery of the year: How did a black hole destroy a star—and what kind of black hole is the culprit?

Astronomers around the world have been on the case since July 2, when they received text messages alerting them that NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope had detected signals in gamma rays, the highest-energy form of light known. Gamma rays are a well-known signature of black holes destroying cosmic objects like stars. That’s because such events release a tremendous amount of energy.

Normally, so-called “gamma ray bursts,” sudden flashes of extremely energetic radiation from the cosmos, last somewhere between a second and half an hour on average. This burst persisted for seven hours, making it the longest gamma ray burst ever recorded.

Another strange clue came from the Einstein Probe, a Chinese and European satellite, which saw x-ray light brightening from the same location in the sky a day earlier. Normally cosmic explosions begin with the highest-energy light and then diminish in brightness, not the other way around. Nothing like this has been observed since the discovery of gamma rays in 1973.

“That made it a very unusual, exotic explosion that we probably had never seen before,” says Eleonora Troja, astrophysicist at the University of Rome, Tor Vergata.

The leading theories about how the stellar murder unfolded describe scenarios that have never been observed. “For me personally, all the different things that it could have been are different versions of exciting,” says Jonathan Carney, doctoral student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who led a study on the event published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

(The brightest blast ever seen in space continues to surprise scientists.)

What we know about this gamma ray burst

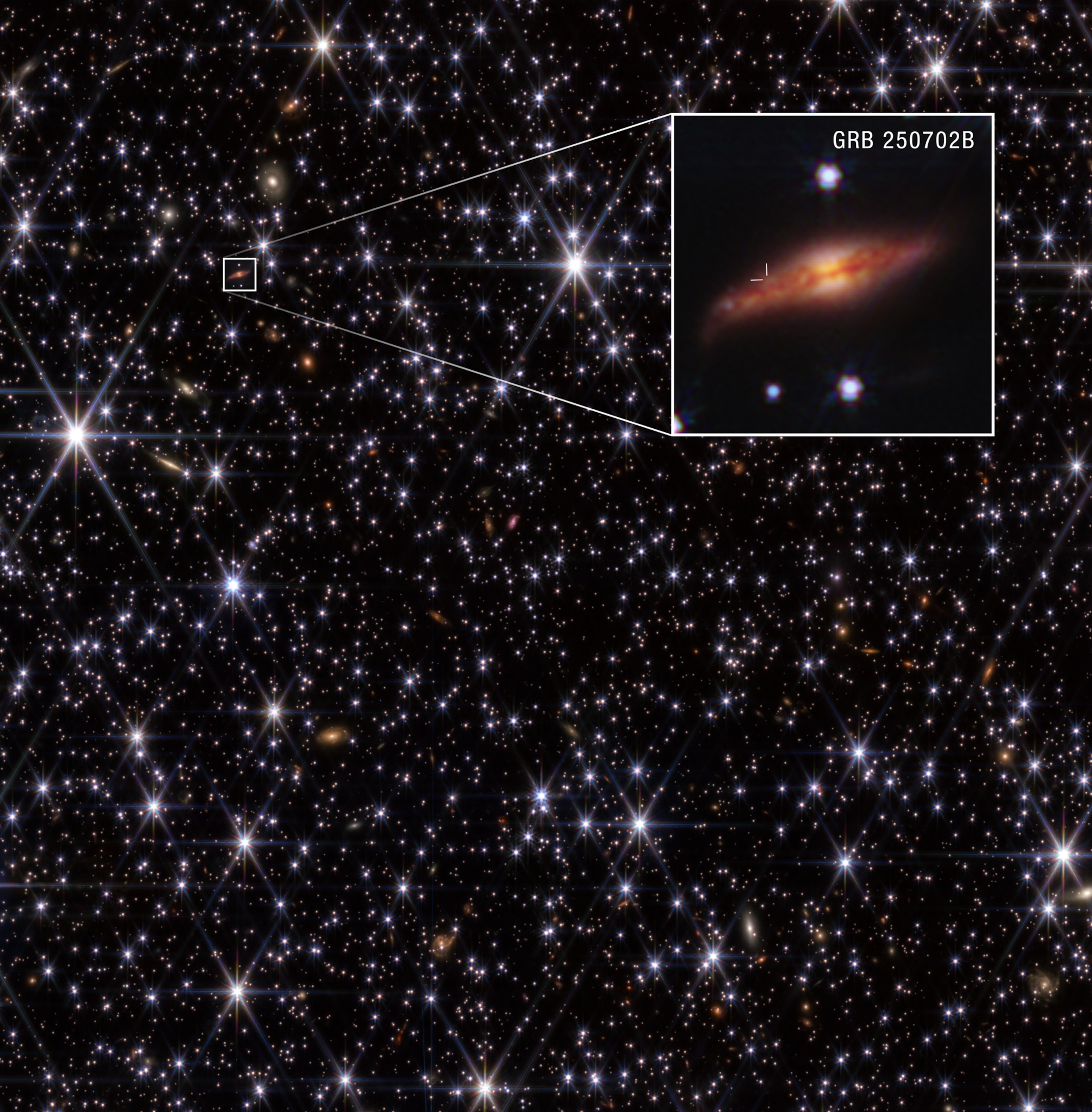

The mysterious cosmic event, called GRB 250702B, has so far generated 10 different papers on the preprint website arXiv.org, some of which are also now published in peer-reviewed journals. Scientists have been using all the tools at their disposal, both in space and on the ground, to investigate.

“We were all still working on Independence Day and writing proposals and trying to point all the telescopes we could at this part of the sky to really understand what was going on,” says Brendan O’Connor, astronomer at Carnegie Mellon University, who led another study on the event also in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Initially, scientists thought the gamma ray signals could have come from inside the Milky Way, which would be simpler to explain. “If it's within our own galaxy, it doesn't have to be anywhere near as powerful as if it's in a very distant galaxy” because the brightness could be explained by a more run-of-the-mill cosmic event that’s relatively close by, says Andrew Levan, an astrophysicist at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

Follow-up observations quickly debunked that theory. Once NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinpointed where on the sky the event had taken place, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile found the fading afterglow next to a smudge the sky, and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope showed that smudge to be a previously unknown galaxy. Then the James Webb Space Telescope, which penetrates through thick cosmic dust using its infrared vision, helped the scientist-detective team figure out that light from the crime scene has been traveling toward us for 8 billion years.

“This was even brighter and more brilliant than you’d have thought, because it was hidden behind so much dust in the galaxy,” Levan says.

Scientists tracking this saga agree that the destruction of the star must have created a jet of particles shooting out of the crime scene at nearly the speed of light, which generated the gamma rays. The big mystery, says Levan, becomes: “What is it that makes that jet happen in the first place? What's sitting in the middle there and actually powering that jet?”

That’s where scientists disagree.

Black hole merges with star before eating it

Some scientists say the gamma ray signal looks like others that have been seen from black holes with about 5 to 30 times the mass of our sun—the smallest black holes we’ve observed. If this fun-size black hole merged with a “helium star,” a star that has largely lost its outer hydrogen layer, something pretty gnarly would happen.

Scientists say that the black hole would begin eating the star from the inside out, creating a jet of high-energy particles and light. When the feeding ends, only the black hole remains.

“That idea alone, I think, is pretty awesome,” says Eric Burns, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University who along with his colleagues present evidence for this hypothesis in a recent study in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. “This should occur in the universe, even given how ridiculous it is, but it's just not something that we've conclusively seen before.”

The smoking gun supporting this narrative would have been observations of a supernova—that is, pieces of the star that were blown out into space instead of eaten. But the thick dust in the galaxy where this occurred, and the alignment with the Milky Way, could have obscured it, even from the view of the Webb telescope.

(Are we living in a black hole?)

Intermediate-mass black hole rips star apart

Other scientists argue the forensic evidence could alternatively point to an intermediate mass black hole as the culprit. That would be scientifically exciting because most black holes in the universe are either stellar-mass or supermassive—weighing more than 100,000 suns. The ones in between, with masses of between 100 and 100,000 suns, are much harder to come by. In fact, there is still controversy about which, if any, known black holes really have an “intermediate mass.”

In this scenario, the intense gravitational pull of a wandering intermediate mass black hole would have ripped apart a white dwarf, a formerly sunlike star that has reached the end of its life. This is a less dramatic way to destroy a star than exploding it from the inside.

The problem with this explanation is that the variability—the ups and downs of the brightening of gamma rays—seen by the Fermi Telescope has only ever been associated with stellar-mass black holes, Burns says.

Specifically, “bigger things just take longer for an event to affect the whole thing,” Burns explains. In practical terms, this means a telescope cannot see brightening and dimming of light more quickly than the time it takes for light to cross the entire black hole. Given that Fermi saw variability on a one-second timescale, this indicates that the black hole has to be relatively small.

While some scientists say the intermediate-mass black hole scenario cannot be ruled out, “to me, this is more like horses versus unicorns,” Burns says.

Another option is that a stellar-mass black hole could have torn apart its companion star, a scenario called a “micro-tidal disruption event” that normally happens with supermassive black holes. This is more plausible than the culprit being an intermediate black hole, says Eliza Neights, a researcher at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center who led the work on the “black hole eating a star” paper with Burns. Still, she and Burns and their co-authors argue the rapid variability of the signal supports the idea that a black hole merged with a star, and then blew it up.

(Here’s how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space.)

The case remains unsolved

For now, quibbles around the black hole’s size and star-killing methods remain unresolved, and some say the jury’s still out on one explanation versus another. Astronomers are currently looking for more clues about what happened by observing the aftermath of the star’s destruction in x-rays and radio waves.

“Every time we open a new window on our universe, we understand that we were not understanding,” Troja says. “It's maybe a reminder of the awe, the awesomeness of our universe.”