Secret Crime-Fighter Revealed to Be 1930s Physicist

Nine recently unearthed notebooks record the true scope of work done by the mysterious forensics pioneer called "Detective X."

For Kristen Frederick-Frost, it all began in the basement of a government science building.

In 2014, the curator was searching the archives of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) for a few things to put in an exhibit. In a box, she stumbled upon nine notebooks that belonged to a scientist who'd worked at the agency in the early 20th century.

This fellow was by all accounts a straight-laced figure, a devout farm boy from southern Indiana who'd gone to college and eventually become a physicist. After earning his Ph.D. in 1916, he went to work at the National Bureau of Standards (NIST's forerunner), where his specialty was measuring things very precisely.

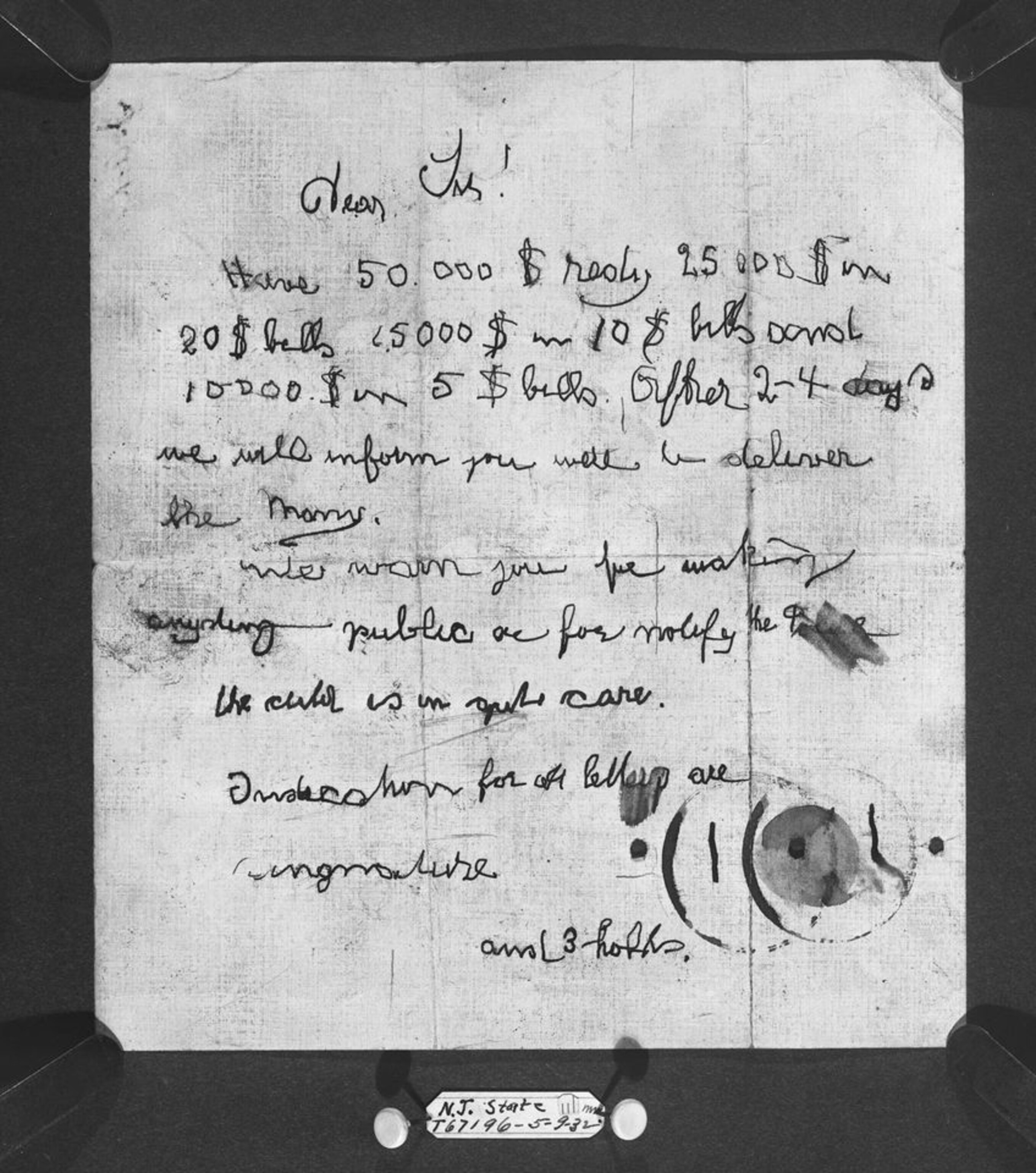

Until now, most of the man's fame was tied to his work on the materials used for dental fillings. When he's mentioned in agency histories, he’s described as the founder of the dental materials research program. The write-up will add, in an offhand way, that he was involved in investigating the murder and kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby, the son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, which happened 85 years ago this month.

“Why in the world would someone like him be involved in the Lindbergh case?” Frederick-Frost says. “That didn't make sense ... you don't do anything, and then all of a sudden you're involved in one of the biggest cases of the century?”

Now, with the newly resurfaced notebooks, Frederick-Frost has uncovered this scientist’s double life as a pioneer in government crime-fighting. (Read “How Science Is Putting a New Face on Crime Solving.”)

The books contain records of cases in which the man performed forensic science analyses—page after page of never-before-noticed evidence that he was a sought-after expert in handwriting analysis, typewriting analysis, and ballistics. All told, Frederick-Frost says he was involved in more than 800 cases.

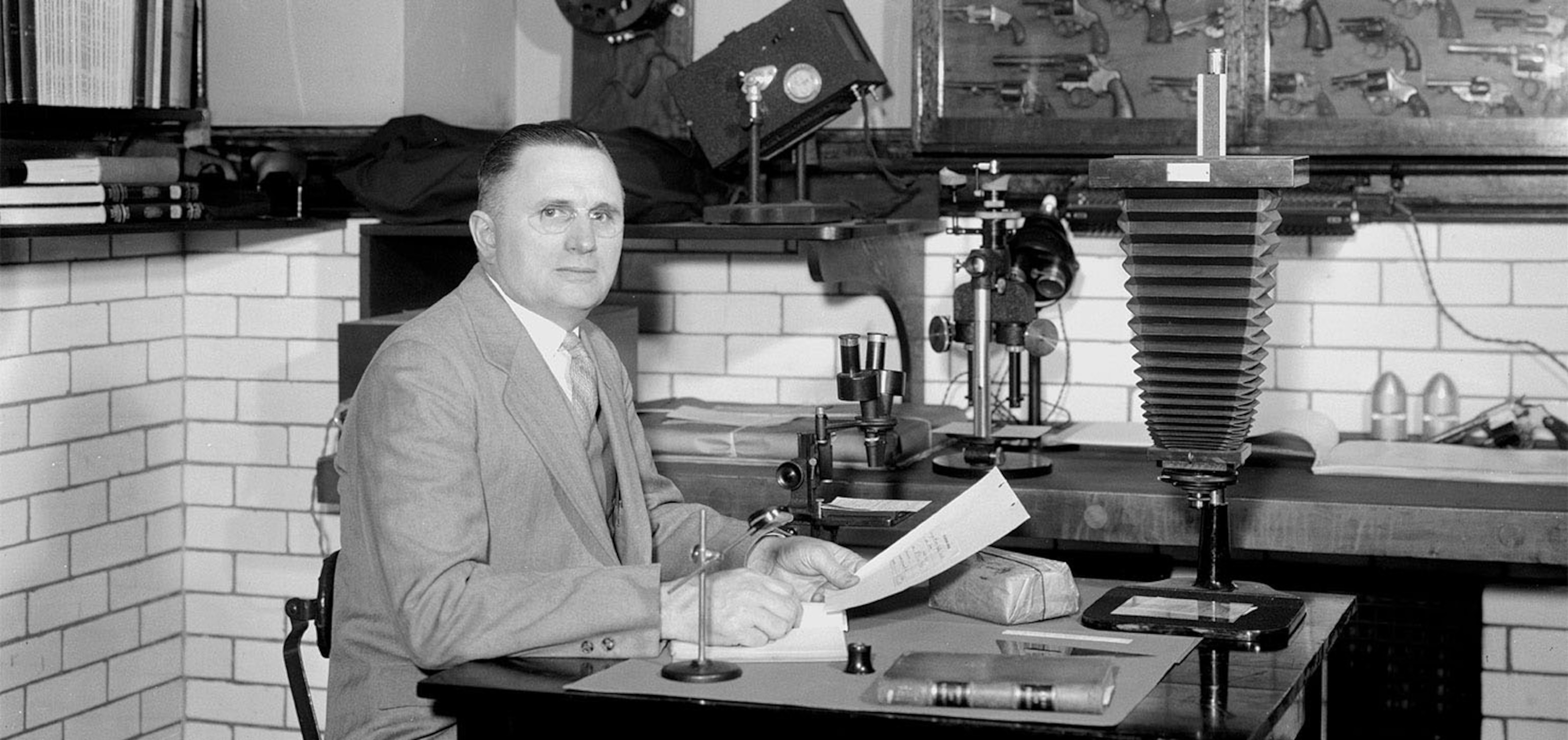

They called him “Detective X” in a 1951 profile in Reader's Digest, but his true name was Wilmer Souder.

Outstanding Expert

NIST is not the first organization you might think of in connection with forensic science. These are the people who maintain the atomic clocks that keep all our phones on the right time. They are also the guardians of the platinum-iridium cylinder that officially defines the kilogram in the U.S.

In a way, though, Souder's involvement makes a lot of sense, says John Butler, a forensic DNA specialist at NIST who worked with Frederick-Frost to uncover Souder's work. The National Bureau of Standards was established to figure out what standards should be set for all manner of things, and to provide expert help on those subjects for anyone who needed it.

Regardless of whether the goal is to decide on the right way to make copper wire or to analyze fingerprints, “you have to measure something well, and then you have to understand the meaning of that measurement,” Butler says.

Indeed, it seems that sometime early in Souder's career, someone called on the bureau to come up with a systematic way to do handwriting and typewriter analysis, probably to detect fraud. Souder, whose specialty was taking exacting measurements and making precise comparisons, was a perfect fit.

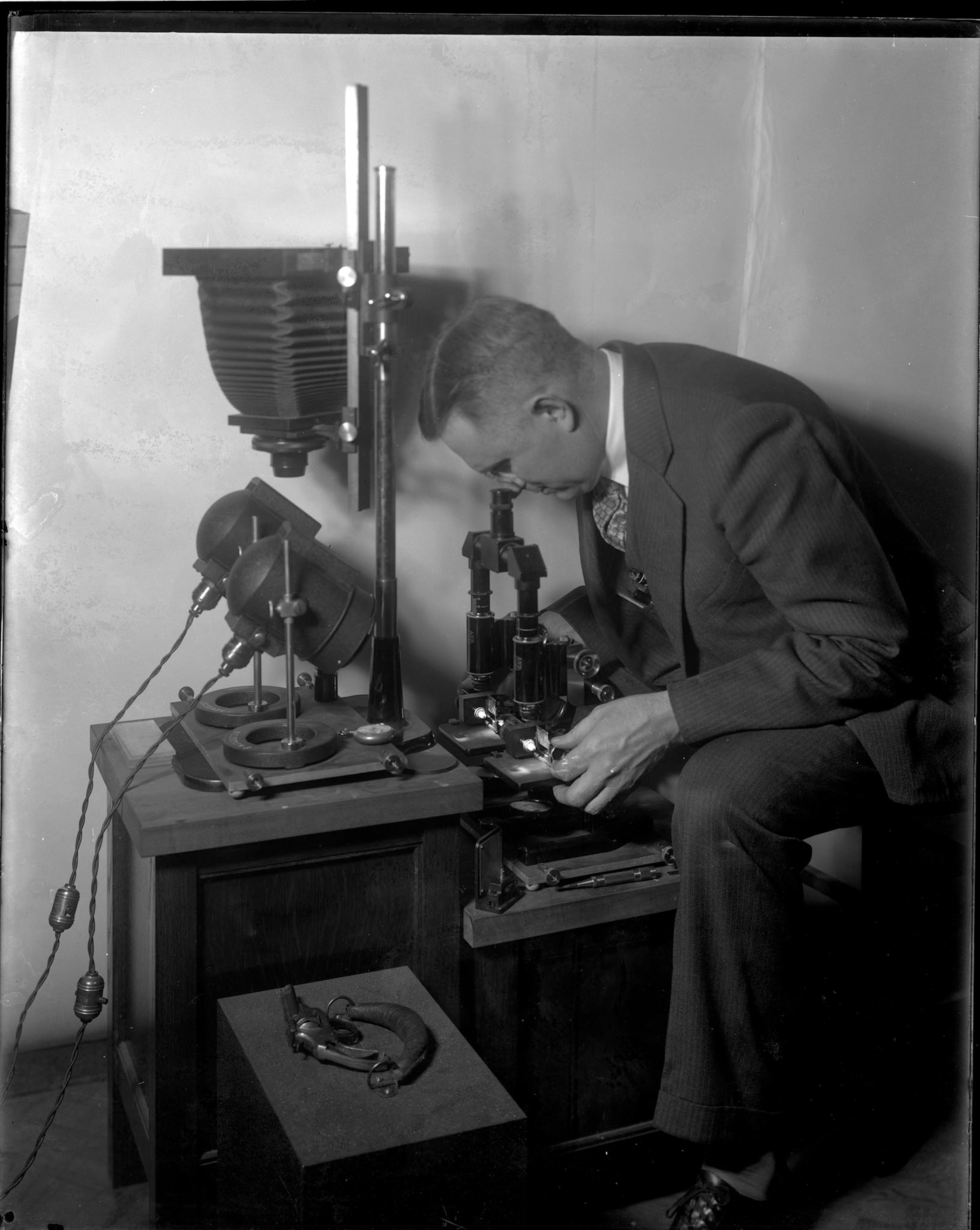

The notebooks show that over the years, Souder worked on all kinds of cases brought to the bureau by the Post Office, the Department of the Treasury, and various other government bodies. In addition to appearing in court as an expert witness, he helped pioneer some of the techniques used in modern forensics in America.

He used a recently invented microscope for comparing bullets to see if they might have come from the same gun. He advised the founder of the FBI's forensic lab. For the Lindbergh case, he analyzed the handwriting on the ransom notes and compared them to suspects' writing, finding a match with Bruno Hauptmann, who was eventually convicted and executed.

Throughout, Souder seems have applied a physicist's sense of statistics and rigor to a field that was not always as scientific as one might hope. The archives of the Secret Service reveal that he spoke at one of their conferences in 1941. Butler, who has seen the transcript of the talk, says that the head of the New York Police Department stood up and called Souder “the most outstanding expert on the continent in the last one hundred years.”

Safety First

Why has Souder's work largely been forgotten, then?

Butler says that part of the issue may be that while Souder published his dental work widely, he worried about criminals learning too much about his methods if he made them public. He wrote articles for trade newsletters and other publications with limited circulation, but not in scientific journals.

It's also possible that he was concerned about the repercussions for his wife and daughter if his involvement in solving crimes became obvious. Souder got a gun permit at about the same time that a pair of men he'd helped put behind bars escaped from prison.

When Souder retired, no one at NIST continued his forensic casework. But today, the agency is part of an effort to come up with standards for forensic science techniques, which have long been lacking.

People have been unjustly imprisoned and even executed after being convicted with evidence from techniques now known to be far less specific, and less scientific, than experts claimed.

Still, it’s inherently difficult to revise the expectations for how a technique should be done and interpreted when the old standards have already been applied in court, says Butler, who is vice-chair of the National Commission on Forensic Science of the Department of Justice.

“One of the biggest things that's impeding progress,” he says, “is that people are fearful of going back and revisiting old cases.” But he sees Souder, who called for just this kind of rigor many years ago, as an inspiration.