Digital cadavers are replacing real ones. But should they?

Dissecting a virtual body has pluses, but some experts say the real thing teaches medical students empathy and respect.

It was the red toenail polish that left one first-year medical student at the University of Colorado breathless—the ineffable reminder that the cadaver he dissected in anatomy lab was once a living person with family, friends, and a tender touch of vanity.

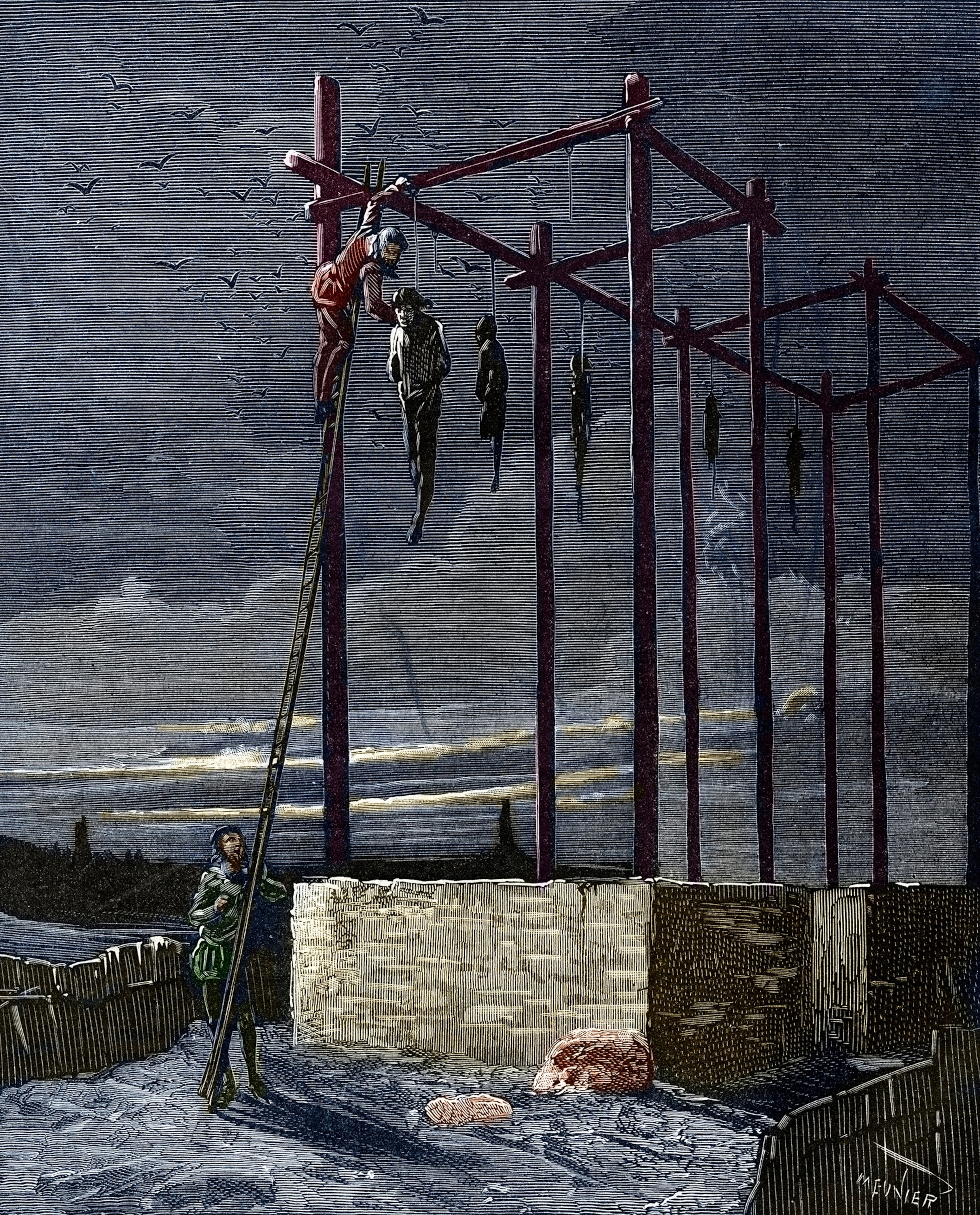

Anatomy, the study of the architecture of the human body, is by tradition the defining course of a doctor’s training. The rite of passage—accompanied by anxiety, fear, and, sometimes, nausea—is “for many, the first encounter with a dead body,” Frank Herlong, a former associate dean for student affairs at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, once said.

But anatomical dissection, like much else, is shifting to digital. (See “The Immortal Corpse,” in the January 2019 issue of National Geographic.) Many medical schools already display virtual cadavers on a screen as reference while students dissect the real thing. Some schools are planning to abandon human cadavers for virtual ones—or already have.

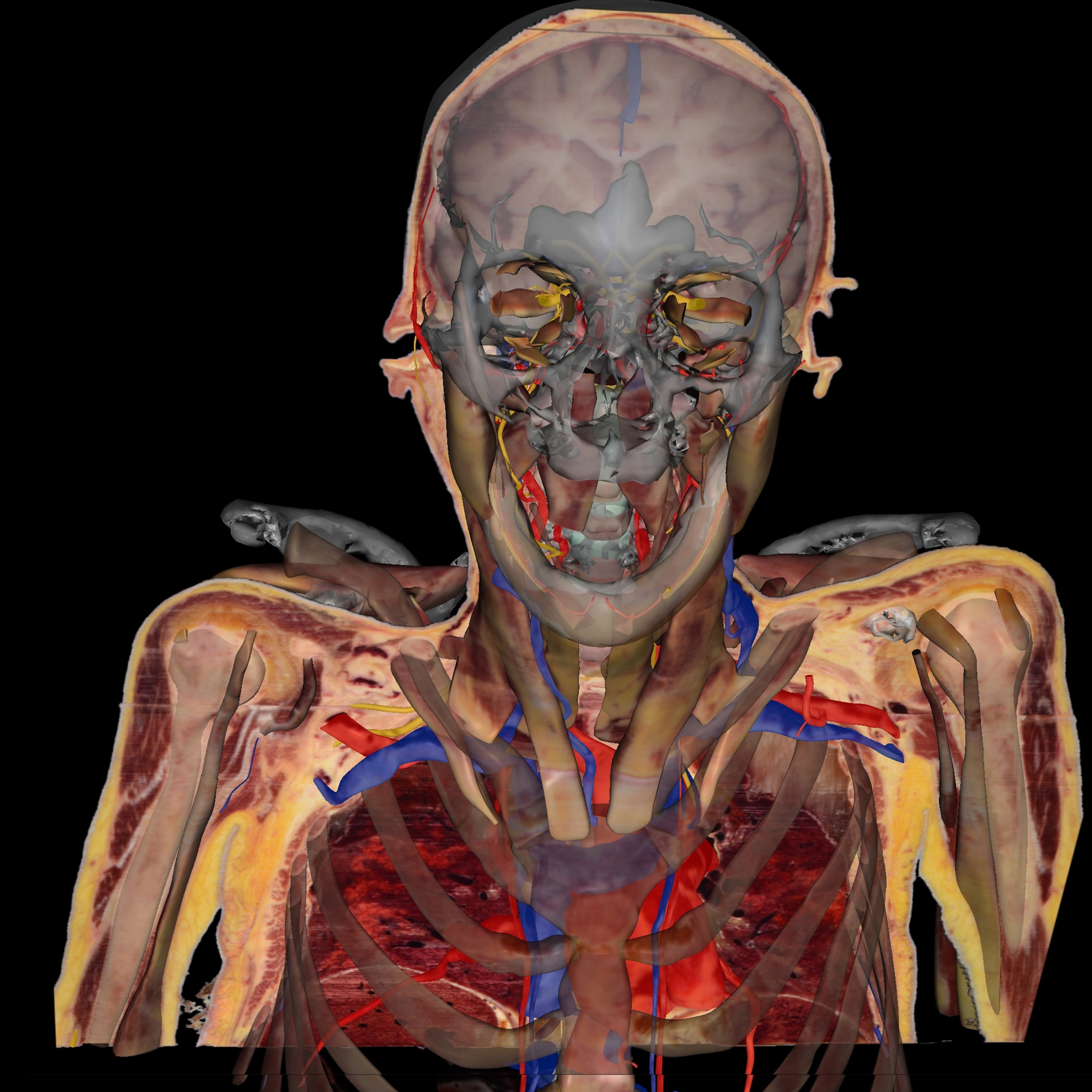

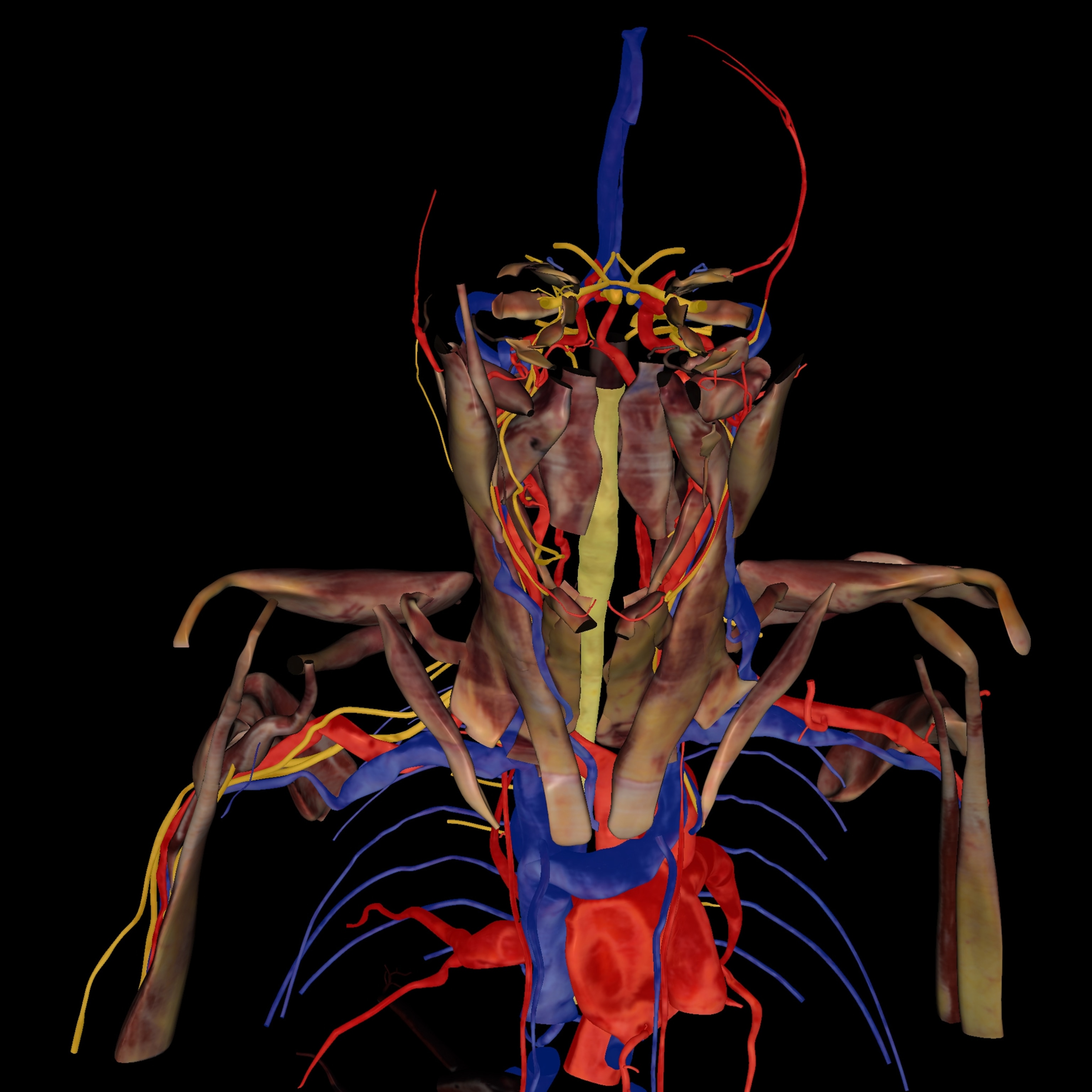

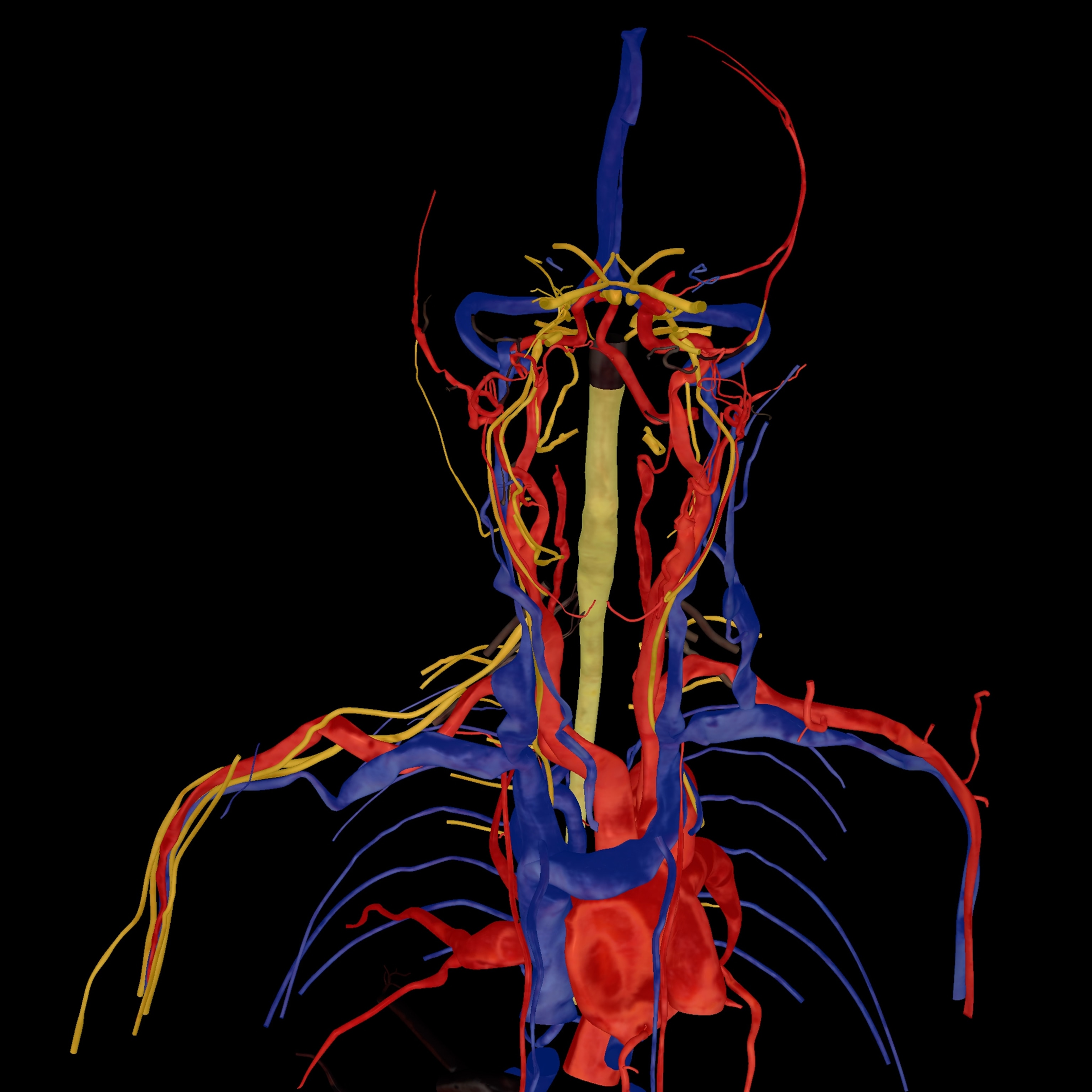

At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Medicine, students dissect a virtual cadaver on six Sectra “tables” (think oversize iPads). The tables feature a 55-inch touch screen with the capacity to rotate, zoom in and out, and navigate inside the 3D images, as well as to virtually dissect tissue.

The medical school opened in 2017, and economics was a significant factor in the decision, says director of anatomy Jeffrey Fahl. “To build a cadaver lab that met government safety and health regulations would have cost about $10 million.” The Sectra tables cost $70,000 each, he says.

Other arguments for virtual anatomical learning include the expense of the cadavers themselves. Although they’re the generous gift of body donors, medical schools pay for transportation, embalming, and storage. The 24 bodies used each year in the anatomy lab at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, for example, cost $1,900 each.

Other factors: The formaldehyde-suffused environment is noxious. And virtual cadavers are more forgiving of mistakes. “It can take hours and hours to pick the overlying tissue off a structure in a human cadaver,” Fahl says. “Sometimes the student inadvertently destroys it. With virtual reality, you simply press ‘reset.’”

Next summer, the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), in partnership with Cleveland Clinic, will open a new cadaver-less health sciences building that will use several digital systems. The CWRU School of Medicine is already using mixed reality with the Microsoft HoloLens, a headset that’s been likened to having x-ray vision, for its HoloAnatomy digital curriculum. And Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine is using virtual reality anatomy developed with a company called Zygote Medical Education.

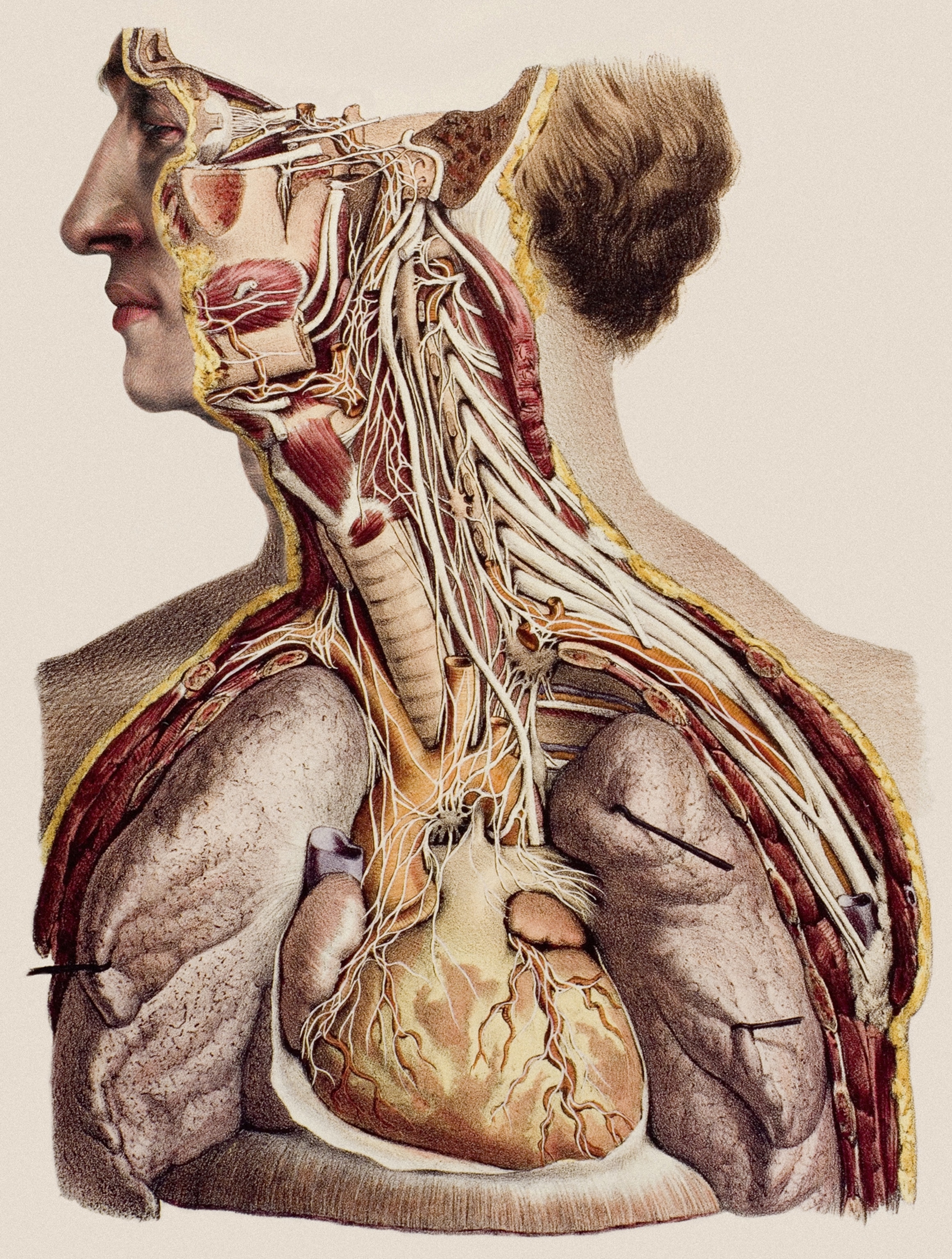

“The heart doesn’t beat in a cadaver,” says Neil Mehta, associate dean for curricular affairs. “You can’t understand how valves work. You can’t observe joint movements.” Virtual reality allows students to experience these things and see features difficult to tease out in cadavers, like structures of the deep inner ear and neural pathways. That said, Lerner will keep its conventional anatomy lab. Human cadavers are still needed for surgery residents mastering their skills.

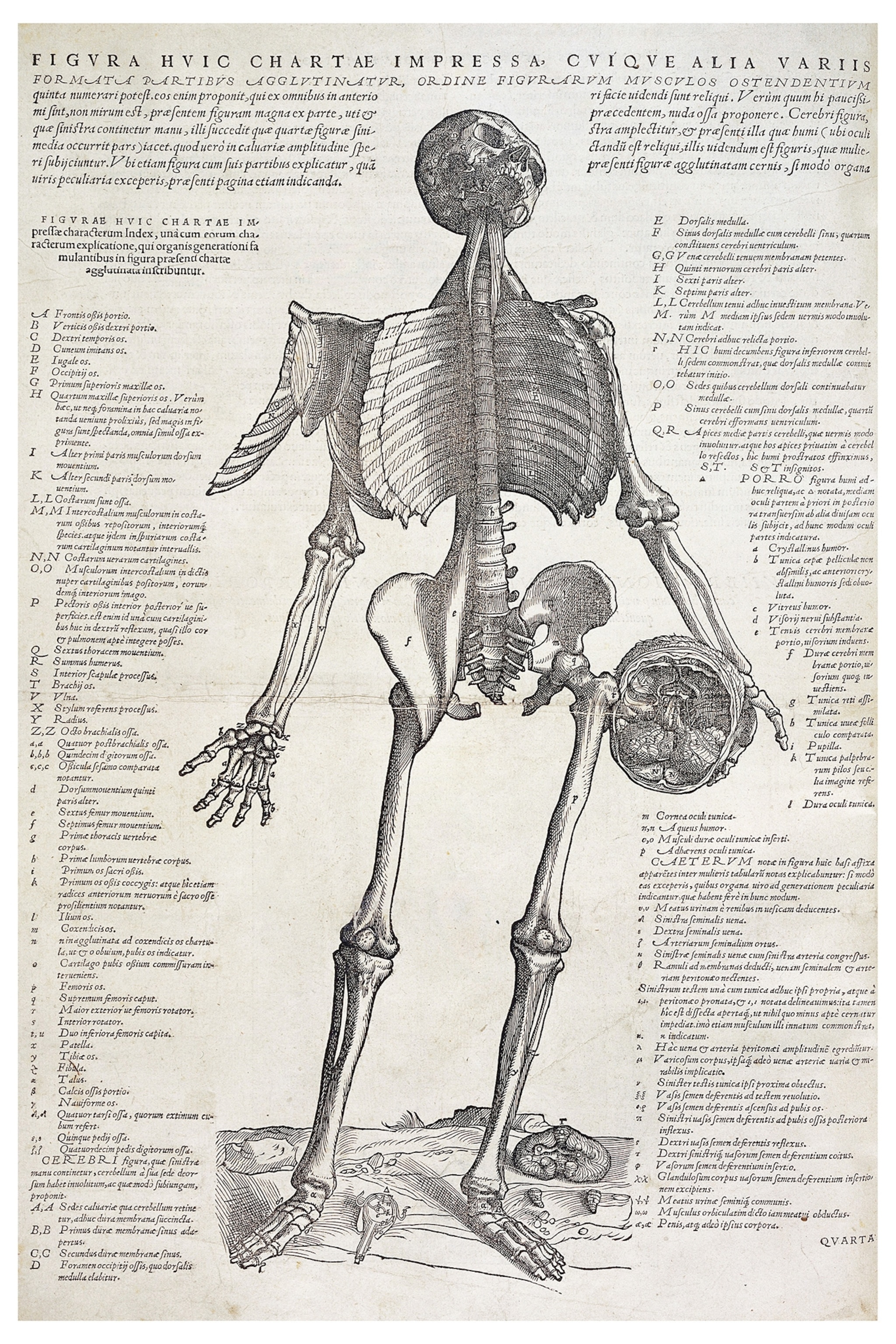

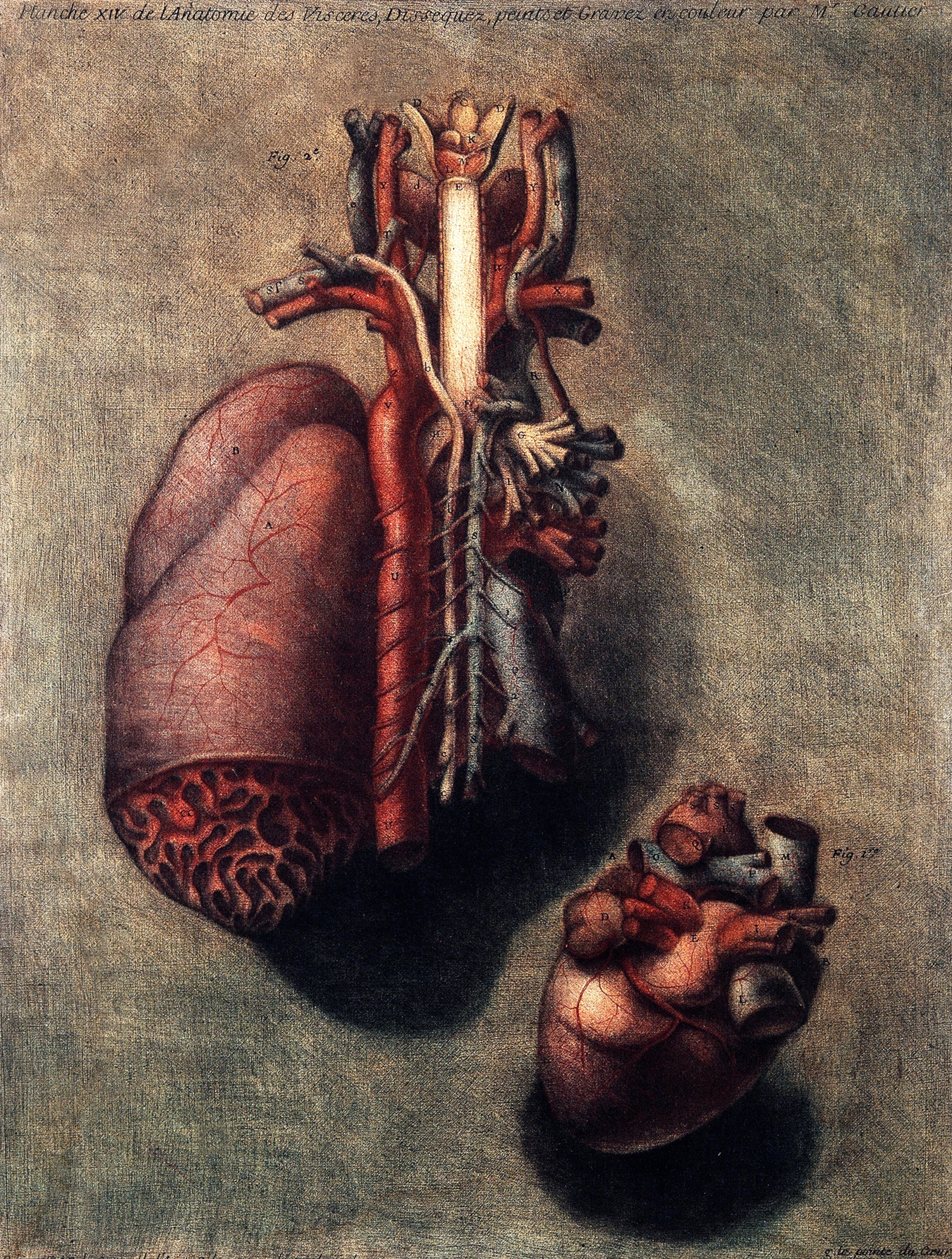

“Isn’t it time we moved on from Vesalius?” asks James Young, Lerner’s chief academic officer. Andreas Vesalius, a professor at the University of Padua, was the first, in the 1500s, to bring medical students to the dissecting table. His landmark reference work on anatomy, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), with its gorgeously detailed drawings of the body, is the analog ancestor of the virtual reality cadaver.

Not everyone is in a rush to abandon Vesalius. At the Stanford School of Medicine, in Palo Alto, California, students use digital dissecting programs, but the human body remains the primary resource. A cadaver teaches more than just anatomy, says Sakti Srivastava, chief of the division of clinical anatomy. It harbors a “hidden curriculum.” As students dissect, they’re reconstructing the story of an individual, he says. “You learn professionalism, team play, respect for death, and empathy—things you will never get from a digital program.”

Srivastava, who trained as an orthopedic surgeon, also values the tactile nature of dissection. “When, for example, a student peels off the tissue and fascia which binds muscle and organs, you will for the rest of your life know what that tissue feels like when you put your hand on a patient.’’ At Stanford, the digital world is a given, he says. “We’re in Silicon Valley and like to keep the best of the old and the best of the new.” But he considers the experience of dissecting a cadaver irrefutably profound. “You can have this wonderful virtual reality tour of Hawaii,” says Srivastava. “Or you can visit the real place.”

Even so, reality has its drawbacks. “An embalmed corpse has challenges,” Lerner’s James Young notes. “The tissues don’t look real, they lose color, and the student is faced with imperfect representatives of anatomy.” Because donor cadavers are generally those of older people, and often diseased, it can be somewhat difficult to learn normal anatomy from them, he says.

As for teaching empathy and respect: “Isn’t it better to learn that on a real human?”