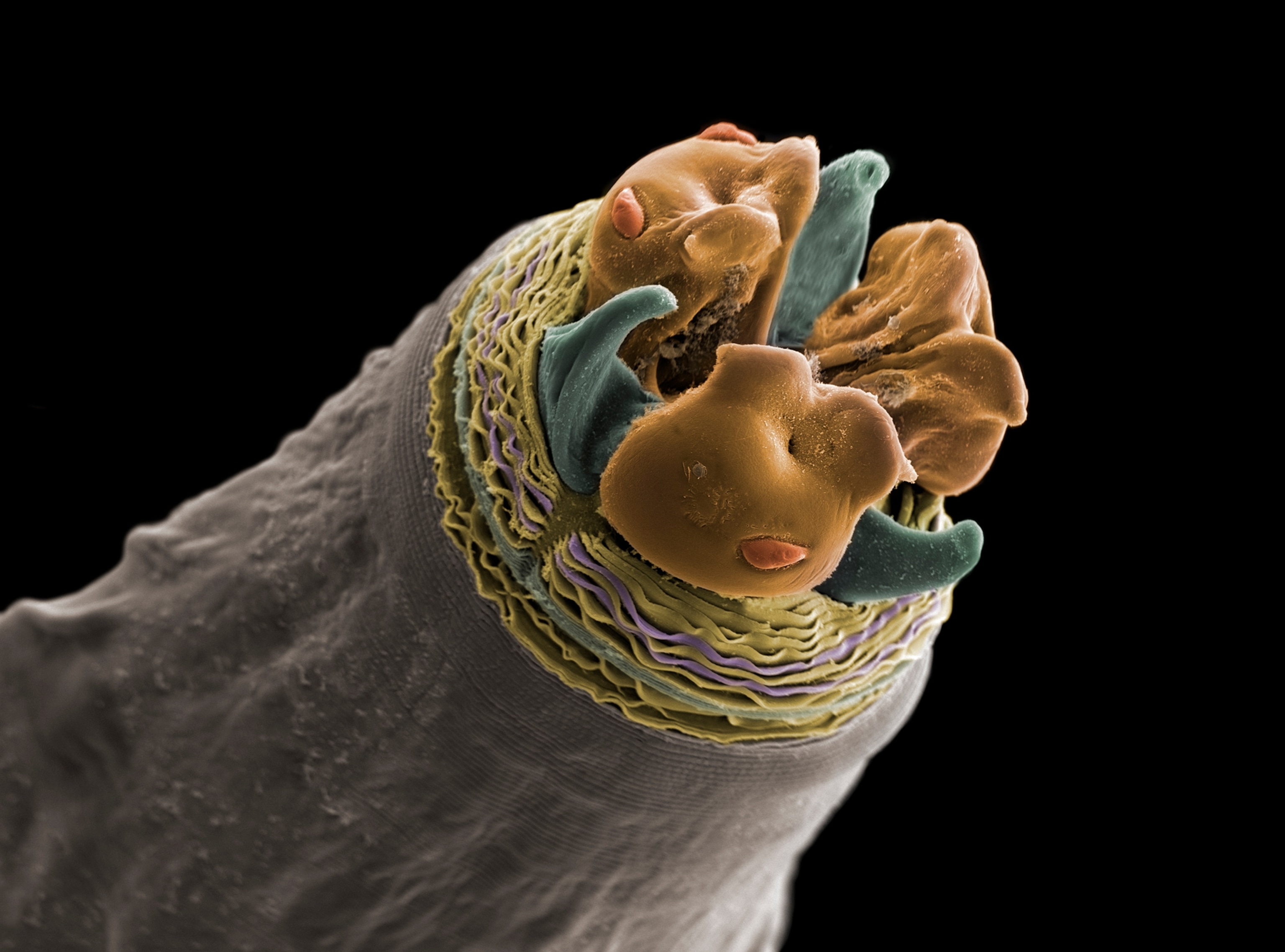

Squirming around in the dirt, a mealworm may seem unremarkable. But if your eyes could magnify the beetle larva by a hundred times, its exquisite face would come into focus. You’d see miniature features that appear so expressive, you might be tempted to anthropomorphize the little rascal.

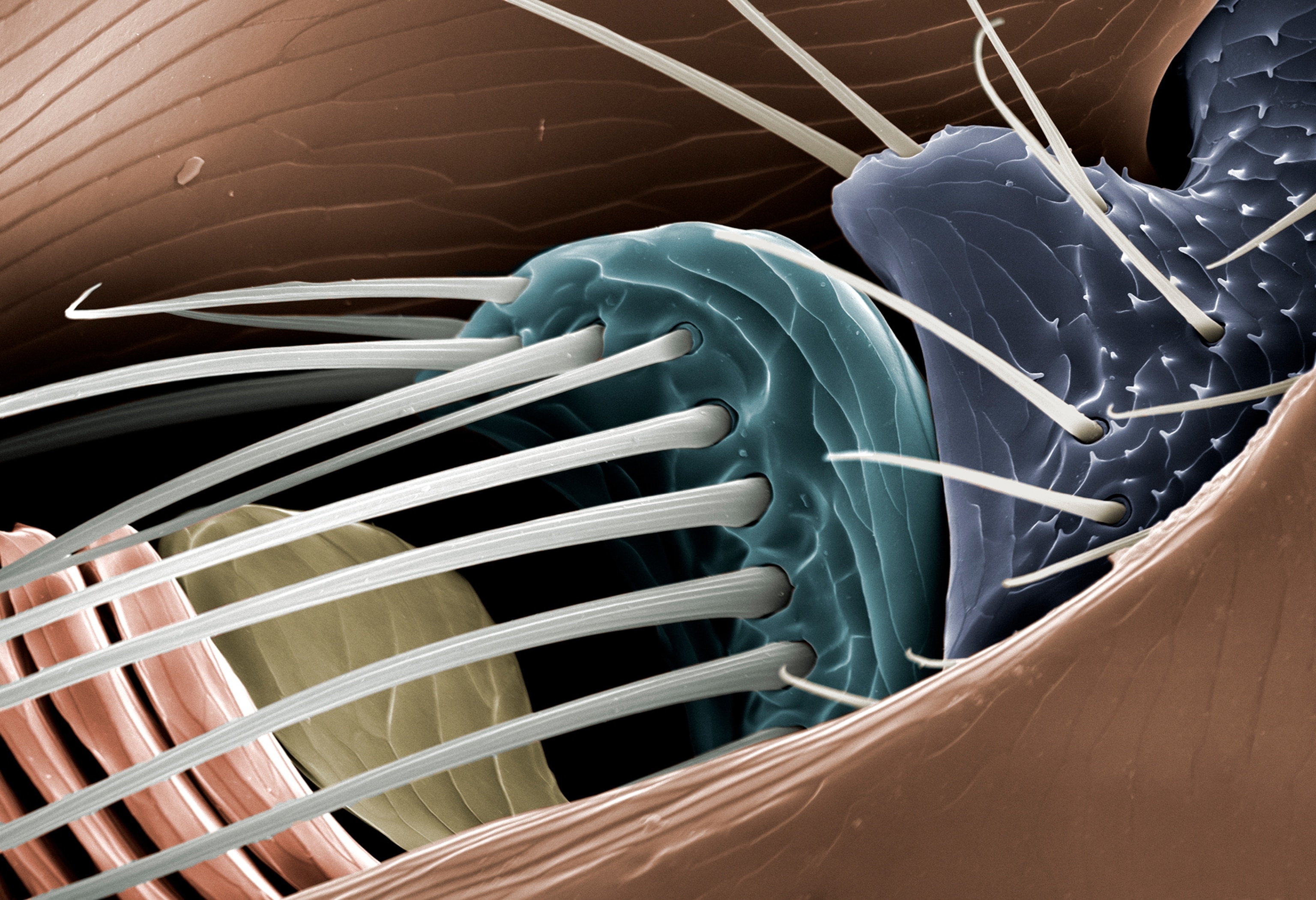

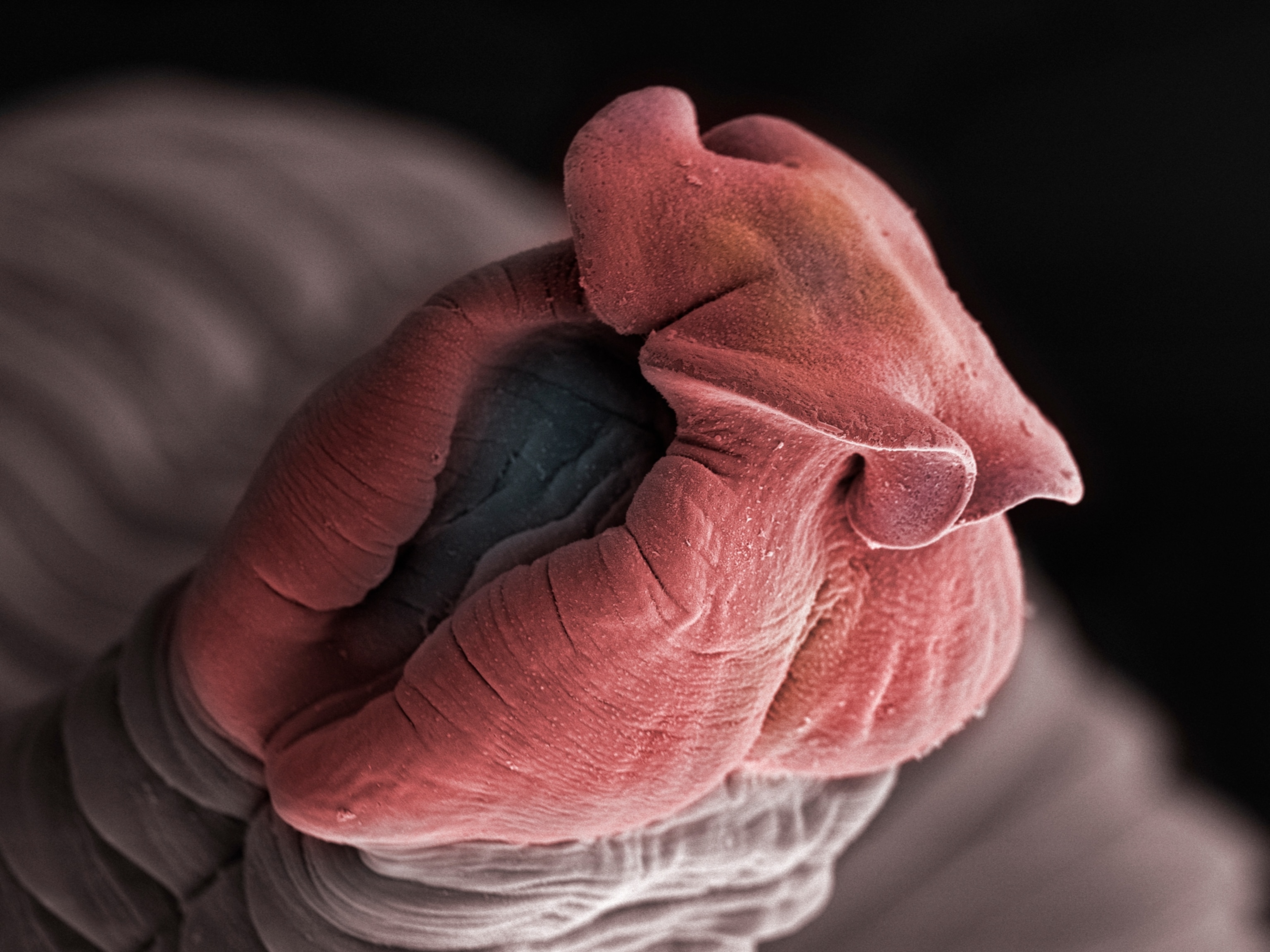

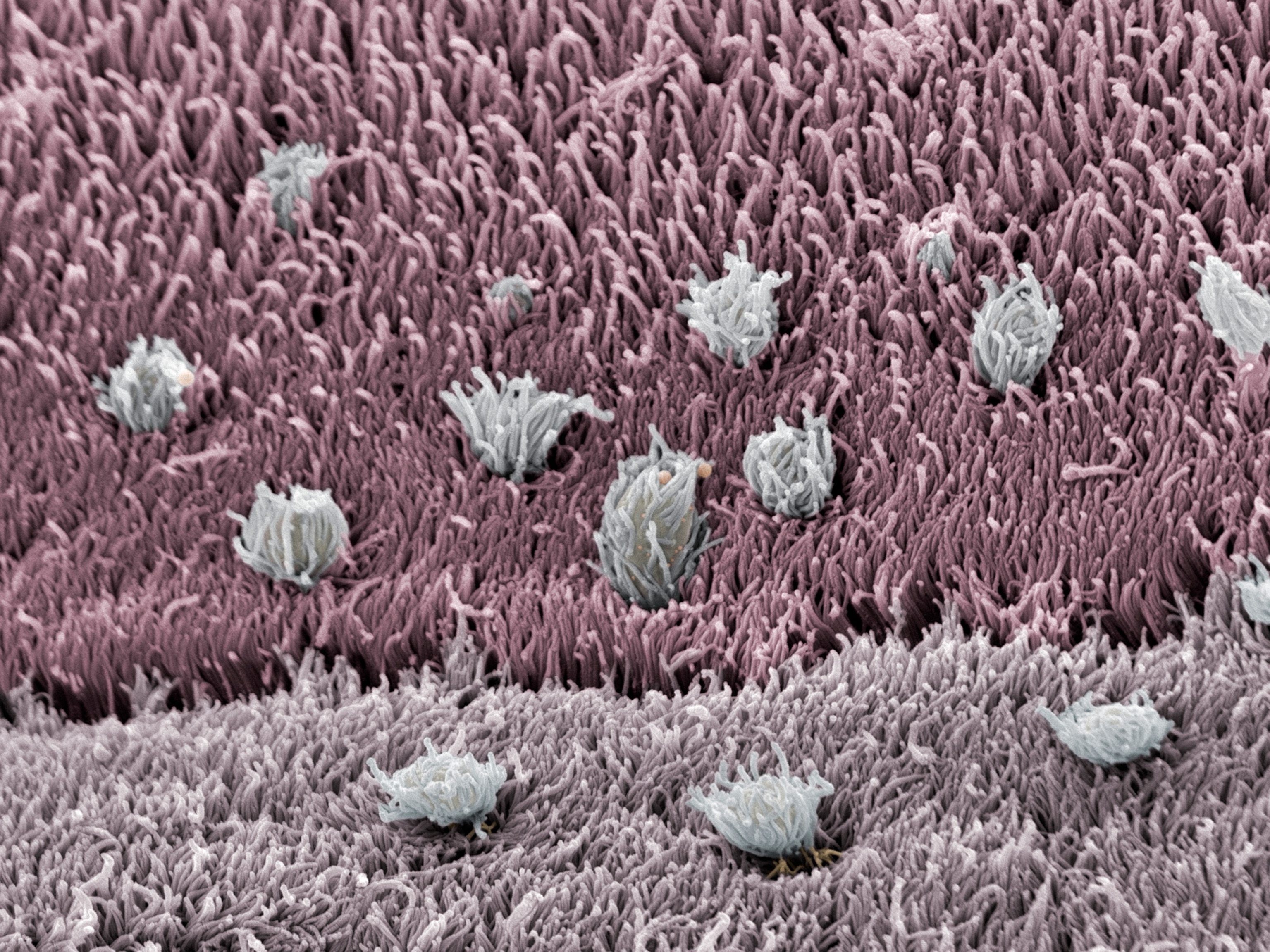

This is familiar territory for photographer Jannicke Wiik-Nielsen. Her portraits of insects, parasites, bacteria, and other exceptionally small life—part of a collection dubbed Hidden World—showcase these creatures in ways that make them look less like “creepy crawlies,” as she calls them, and more like characters. She achieves the effect through scanning electron microscopy, a technique that yields high-resolution images through the use of electrons instead of photons.

“Electrons have much shorter wavelengths than light waves,” she says, “which [enables] much better resolution than an ordinary light microscope.”

In scanning electron microscopy, a focused electron beam captures a high-resolution, grayscale image of a specimen by scanning its surface. Because the beam is sensitive to dust and water, this scanning is done inside a high-vacuum chamber. After Wiik-Nielsen collects a specimen, she places it in a solution that helps maintain its structure. Then she dries the sample thoroughly and gives it a thin coat of metal. This helps the specimen stay intact throughout the imaging process, which takes just a few minutes. Once an image is made, Wiik-Nielsen uses Photoshop to colorize it. (See what mites look like under a scanning electron microscope.)

“Depending on the purpose of the photo,” she says, the colors are manipulated to replicate what she's able to see with her own eyes, or, in other cases, “the colors may be manipulated in an artistic form," or left as black and white.

Wiik-Nielsen’s passion for electron microscopy took hold six years ago. As a research scientist at the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, she was studying fish eggs that had been infected with a fungus, as well as an amoeba that creates gill disease in farmed salmon. Her photos of the amoeba caught the attention of the institute’s aquaculture biologists and breeders, she says, “who at long last could actually see the parasite that they were trying to fight.” Wiik-Nielsen was fascinated by the microscope’s capacity to magnify the organisms up to 200,000 times, and it soon became a research tool of choice.

Her favorite subjects are parasites. Though they may seem gross to many people, Wiik-Nielsen says, things like tapeworms and roundworms become incredible when amplified by an electron microscope. The images reveal the creatures’ physical characteristics—mouthparts, for example, or the tiny protrusions called microvilli—in wild detail. (Meet 5 "zombie" parasites that mind-control their host.)

Even blood-sucking (and Lyme disease-spreading) deer ticks captivate Wiik-Nielsen. In an ode to a tick she encountered and then photographed, she wrote, “I was disgusted when you landed on my shoulder. You thought I was a deer who could save your life. Instead I was a human who could end your life. Now, looking at your face, I feel anything but disgust.”

In addition to using the electron microscope to image specimens for research, Wiik-Nielsen uses it—with the institution’s permission and support—to image things she finds in her garden, or when exploring outside with her two young daughters.

“We find crustaceans in the tidal waters, pollen from plants and trees,” she says. “Only our fantasy can limit us!”