Recent Hurricanes Pushed Rare Island Species Closer to the Brink

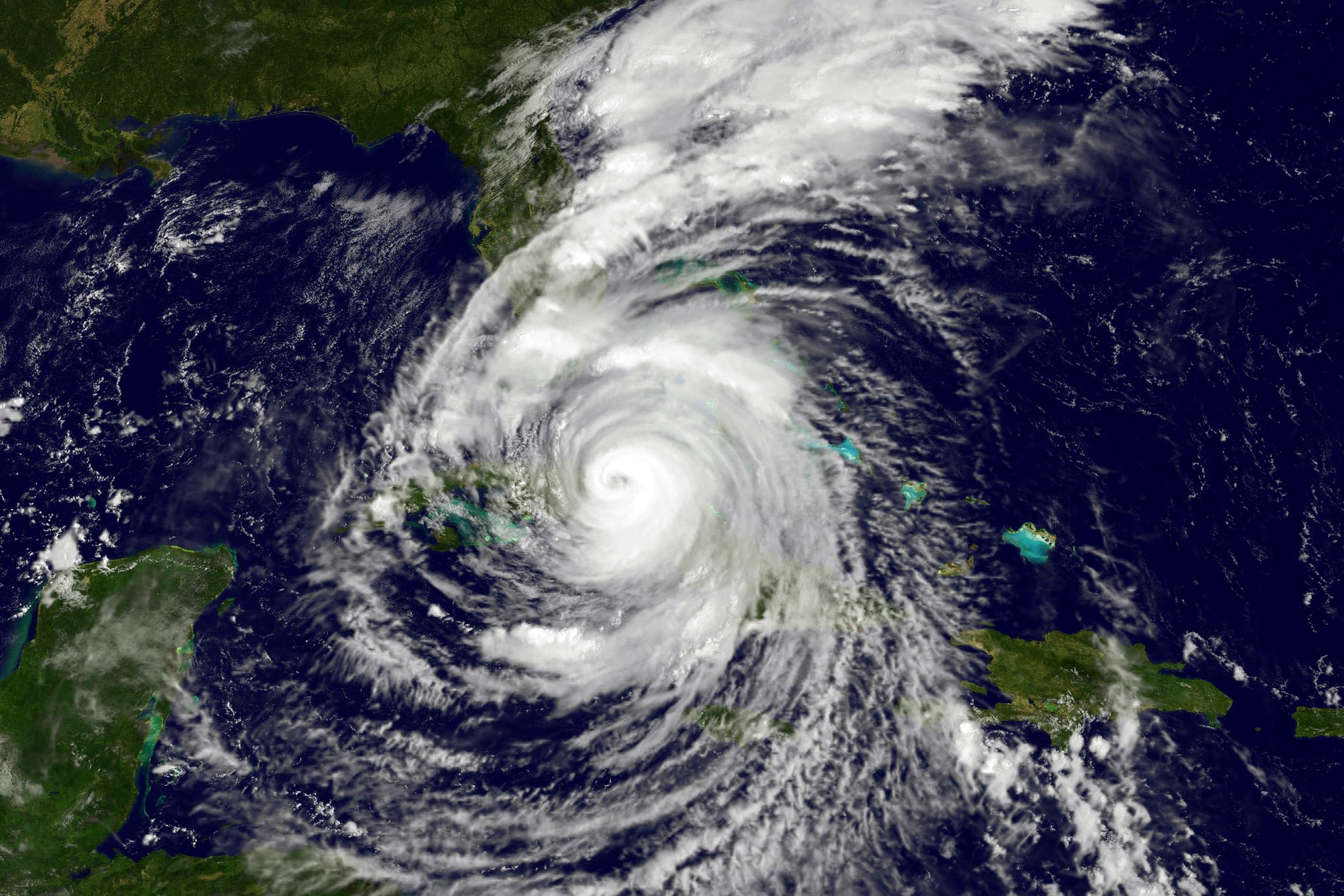

From the iconic Key deer to rare birds, insects, and plants, the wildlife of the Florida Keys took a beating during Hurricane Irma. Can it recover?

As Hurricane Irma slammed into south Florida in September, Dan Clark, manager of a complex of four national wildlife refuges in the Florida Keys, had evacuated and was at his mother’s house near Tampa. His eye was on the weather and his mind was on the multitude of plants and animals that inhabit the unique refuge system he oversees, which includes the well-known Key Deer National Wildlife Refuge.

There are about 20 federally endangered species in the Keys, and many of them exist nowhere else on Earth. “The dang eye of the hurricane tore right through the prime habitat for many of our most at-risk species,” said Clark.

One animal of particular concern was the Key deer, a charismatic, small subspecies of the white-tailed deer. Key deer were nearly eradicated by poaching during the 1950s, when the population dropped to 25. North America’s smallest deer, the animals rarely weigh more than 95 pounds and stand about three-feet tall at the shoulder. They live only in the Florida Keys.

“The deer can swim well, even in a storm surge situation, but not in 130 miles-per-hour winds,” said Clark.

According to Clark, there is no typical hurricane response for the deer. “With Irma,” he said, “I imagine they did everything from hiding behind garages to hunkering down in bunches of vegetation to running wildly through the street—it worked out well for some, it worked out poorly for others.”

Thanks to a survey conducted after Hurricane Irma by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Texas A&M University, and released in mid-October, we know just how well: About 14 to 22 percent of the Key deer population, which is estimated to be about 1,000 deer, was killed by the storm. Deer were found crushed by debris and impaled by wind-blown objects.

“If you are in the eye of a hurricane and you are wildlife,” says Clark, “it’s like Dorothy’s house: you are going to get thrown around.”

Kiddie Pools to the Rescue

But deer that survived the storm faced new threats. To live on these low-lying islands, where the height across much of the deer’s habitat is a mere three feet above sea level, the animals need freshwater. Normally, they get that from freshwater marshes and holes in the coral rock. But Irma’s storm surge washed over much of the core habitat for Key deer, inundating critical watering holes with salty ocean water. About five days after the storm, the first refuge biologists returned to Key Deer National Wildlife Refuge. Seeing the lack of freshwater for animals, they improvised a unique solution: kiddie pools.

A fleet of fire trucks and police and refuge vehicles delivered about a dozen of the store-bought blue plastic pools, roughly the size of a small trampoline, to key locations between Sugarloaf Key and Big Pine and No Name keys. The pools also provided freshwater for other species, such as butterflies, dragonflies, and the endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbit.

“We don’t take the decision to do something like this lightly,” said Clark. “The refuge is not a zoo, and we would prefer not to habituate wildlife to people. But based on the data we collected, the amount of overwash was significant enough that freshwater resources were limited.”

Rare Plants and Animals

But not all Keys endangered species could be helped as easily. Among those at risk are the Key tree-cactus, whose only wild population grows on Big Pine Key. That plant species got “obliterated” by Irma, said Clark. The population of the highly endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbit remains unknown since the storm. That animal’s scientific name, Sylvilagus palustris hefneri, honors contributions to research on the species made by late Playboy icon Hugh Hefner. Also unknown are the post-Irma populations of Bartram’s hairstreak, a butterfly found only on Big Pine Key that depends on a plant also found only on that one island.

Then there are species like the magnificent frigate bird, whose only nesting population in the continental U.S. is nearby, on the Dry Tortugas. That bird, which has a seven-foot wingspan, used to nest on some of the more remote mangrove islands in the Keys. But human disturbance appears to have driven them off.

“The real question,” said Clark, “is with sea level rising and more intense and frequent storms hammering these islands: What is going to happen in the future for these species?”

The Florida Keys dangle from mainland Florida like a bracelet slipping off a wrist, an archipelago of 1,700 tiny islands formed largely from old coral deposits. The islands separated from mainland Florida around 15,000 years ago, as the last ice age receded and sea levels rose, stranding animals like rabbits and deer on the Keys and enabling them to form subspecies that developed to fit the unique island habitats. Yet the islands are special for humans too, and lately more and more people have been drawn to the nearly tropical paradise.

“Development on the Florida Keys really exploded in the 1980s,” said Bonnie Gross, who has been writing about Florida for 40 years, first as a reporter with the Sun Sentinel, and now as co-host of the outdoor travel website Florida Rambler. One problem, said University of Florida wildlife ecologist Bob McCleery, is that high ground is prized by developers. As seas rise and species move inland, they run into humans. There is “an ongoing squeeze of coastal ecosystems between rising seas and development,” stated a 2012 research paper co-authored by McCleery and published in the journal Global Change Biology. Research cited in the paper shows sea levels in the region have risen at a rate of about an inch a decade in the past century, and the rate has increased since 1990.

More Threats to Rare Species

Introduced species pose an additional threat to the Keys endangered native species. Clark’s colleagues recently pulled a 167-pound Burmese python out of Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge, in the Upper Keys. Green and spiny-tailed iguanas, both introduced from the pet trade, are also now present throughout the Keys. And the spiny-tailed iguanas eat eggs and small birds. Ornamental plants that invade into native habitats are a problem, too, such as latherleaf and Brazilian pepper.

“Non-native plants really love disturbance,” said Clark, such as right after a hurricane moves through. “Things here are so disturbed now that any number of plants could easily come in and become established.”

One of the most critical resources for endangered Keys species is freshwater, which exists in relatively deep lenses on several of the larger lower islands. But as seas rise the outer edges of these lenses become increasingly brackish, reducing the amount of available freshwater for species like the Lower Keys marsh rabbit and Key deer.

“At a certain level of sea level rise there won’t be any freshwater there,” said Danielle Ogurcak, a postdoctoral researcher at Florida International University’s Institute for Water and Environment. “It is just a question of how quickly that happens.”

For Gross, the longtime Florida reporter and rambler, that will be sad news indeed. “I love the deer,” said Gross.

She first spotted them on a trip to Big Pine Key with her husband and two young daughters more than 20 years ago. “We were sitting on our patio and suddenly they just emerged,” said Gross. “We actually were whispering, because we didn’t want to disturb them.”

But Gross, who presently lives on the water in Fort Lauderdale, knows all too well the perils facing the Keys. “I have seen sea level rise in my lifetime,” said Gross. “I know the Keys are special, but they may just be one of those places that people have to see before they are gone.”

“What will happen in the future is the big moral and ethical question that folks will have to decide,” said Clark. “Not only for Key deer, but a whole bunch of island species. As islands become more and more threatened by cataclysmic events, we are going to have to make difficult decisions as a society on how we are going to keep these species.”