'An interest in science is now forced on us.' Ian McEwan on navigating the territory where fiction meets reality

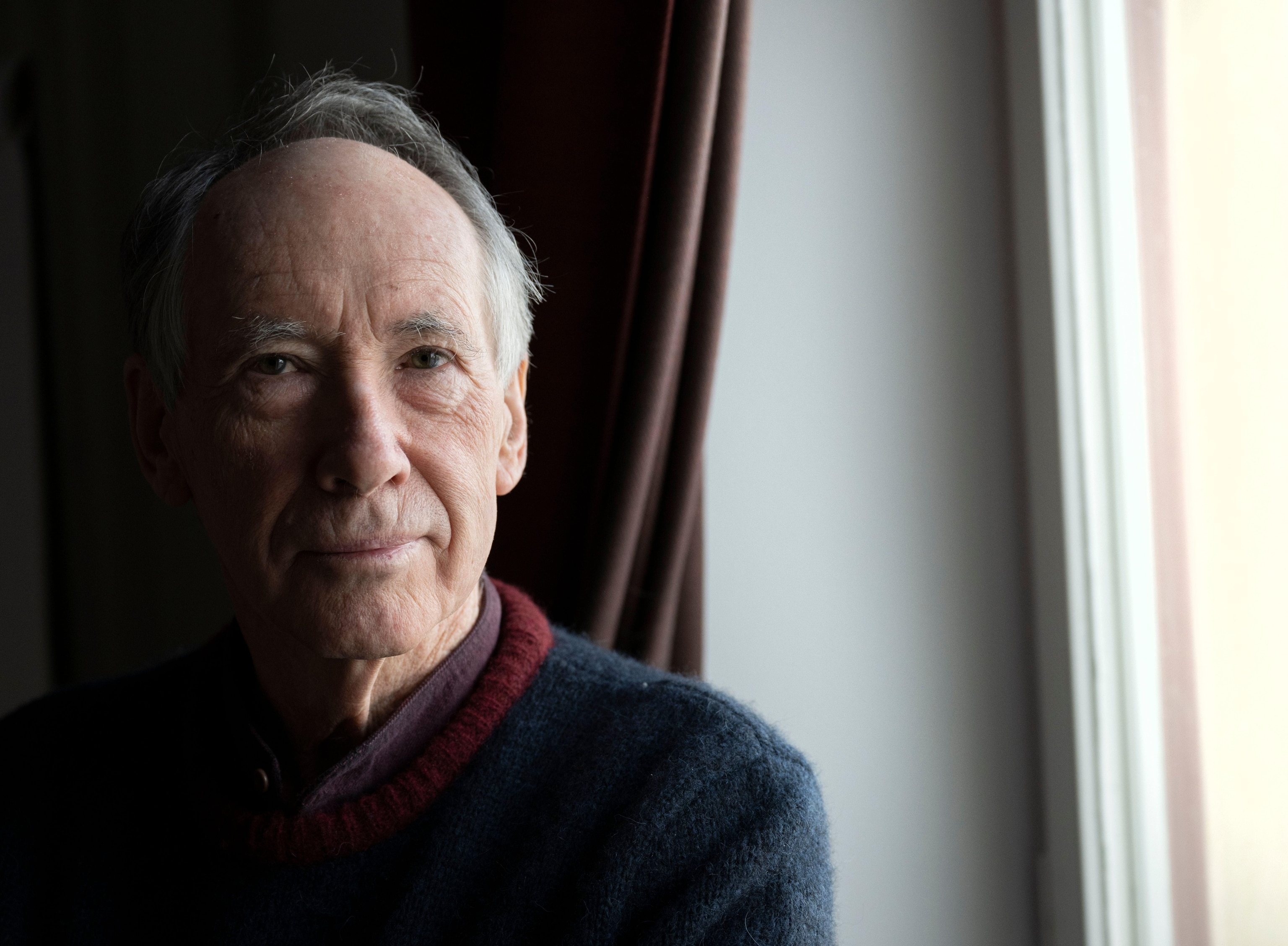

The British novelist was once described as a 'chronicler of the physics of everyday life.’ With a body of work suffused with scientific fascination, what does he see as the novel's role in humanity's reckoning with its darkest threats?

In a London operating theatre, a bone flap was cut from an anaesthetised patient’s skull, and Ian McEwan was permitted to place his gloved finger on the brain of a living human being. The novelist was shadowing neurosurgeon Neil Kitchen, of the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, as research for his novel Saturday (2005), which chronicled a tumultuous day in the life of a neurosurgeon. But this simple touch symbolised the profound fusion of McEwan’s parallel interests in science and human emotion. As a scientifically-literate cultural titan, whose interests range from biology to cognitive psychology, he relished the empirical research. But as a novelist of the human condition, whose books probe the chaos, beauty and violence of our emotional lives, McEwan realized that he would rather touch the brain of his fellow homo sapiens than journey to Mars.

“I felt a sort of awe,” reflects McEwan. “People say the human brain is the most complex thing in the known universe, with the possible exception of the universe itself… How could a physical object give rise to dreams, hopes, loves, hates, ideas and memories? So putting my finger on it was really a symbolic act. I asked Neil if I could, and he said: ‘Yes, but not too hard.’ The surface was quite robust… And it [the moment] was very moving. I don’t know whose brain it was… But I was well aware that it was rather intrusive.”

(Related: The audacious science pushing the boundaries of human touch.)

British novelist McEwan, 74, has dedicated his life to illuminating the complexities of human nature. His body of work—full of astute character studies and nuanced morality tales—has explored love, war, murder, stalking, climate change and artificial intelligence. His best-known novel, Atonement (2001) was translated into 42 languages and adapted into an Oscar-winning film. He won the Booker Prize for his euthanasia-themed novel Amsterdam in 1998. His latest novel Lessons (2022) examines the interplay between global events and private lives, through the scarred life of McEwan’s regretful alter ego Roland Baines.

However, it is McEwan’s deep respect for science which distinguishes him from many other literary novelists. He wants to know what neuroscience, biology and psychology can teach us about ourselves. A polymath and humanist, he reads scientific journals, converses with scientists, and pens scientific articles. His “intellectual hero” was the late American biologist E.O. Wilson—a rationalist who celebrated the empirical beauty of life on earth, and who pleaded for a glorious ‘consilience’ of diverse fields of knowledge.

But McEwan’s scientific interests have, at times, made him an outlier in the cultural sphere, inviting quizzical frowns and head tilts. Amitav Ghosh, another science-savvy literary novelist, has noted that to write about scientific themes like climate change is “to court eviction from the mansion in which serious fiction has long been in residence.”

“I don’t know why my interest in science is so strange to people,” says McEwan. “When my inquisitors ask about it at literary festivals, it is as if I have spent my life thinking about numismatics [the study of coins]. Once, if we wanted to know about the solar system, we asked a priest. But they turned out to be wrong on just about everything to do with the material world. So if you are interested in the world, science is a part of that. And an interest in science is now forced on us because we carry around extensions of our prefrontal cortex in the form of smart phones, so we have moved en masse into a world of technology, whether we like it or not.”

Progress and regression

In 1959, C.P. Snow—a British scientist and novelist—gave his “Two Cultures” lecture, which mourned the “mutual incomprehension” of science and the humanities. “People still go off to do English, French and history on one side, or maths, chemistry and physics on the other, so we have gotten nowhere on the very things that C.P. Snow complained about,” says McEwan. “And we have [British government] cabinets that are packed with people mostly from Oxford who did philosophy, politics and economics, or Classics, [who] then have to negotiate the pandemic—often from a basis of not only ignorance but even hostility to rational thinking.”

It's true that suspicion of science seems on the rise. Research monitoring public opinion across 17 countries, including the U.K. and the U.S., found that respect for scientists remains high, but science skepticism rose from 27% in 2021 to 29% in 2022—though remains lower than in the three years before the pandemic. Skepticism of principally human-caused climate change has also grown to 37% worldwide. A study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that these “anti-science attitudes” are partly due to science’s perceived conflict with people’s identities, beliefs, morals and knowledge, and the “toxic ecosystem” of modern politics: “Many individuals would sooner reject the evidence than accept information that suggests they might have been wrong.”

At a global level, McEwan is troubled by the competing waves of scientific progress and seemingly regressive human behavior. “Even as we are having discussions about the ethics of gene splicing, possible interference in developing human embryos, or splicing DNA in agricultural products, we're also facing matters that are so ancient they almost override it,” says McEwan. “We have sewage pumped into rivers. We have an all-out war in Ukraine, which looks like a curled-up old black and white photo: the ruins of cities look like… 1945. We also get that sense of the cutting-edge new mixed with the medieval old when you're tracking conspiracy theories on the internet: [some seem] as superstitious and immune to critical thinking as they were well before the scientific revolutions.“

Science cannot solve all the world’s problems. Nor can it satisfy humanity’s deepest needs, as McEwan’s own emotionally tangled novels illustrate. Although rational thought is “one of our saving graces,” he insists, it requires “the enrichment” of human emotional forethought. The late physicist Steven Weinberg acknowledged: “Nothing in science can ever tell us what we ought to value.” But in addressing key contemporary issues such as climate change skepticism, pervasive disinformation and potentially corrosive academic divisions, McEwan hopes humanity can at least strive collectively towards a more ‘scientific’ mode of thought. “For vast numbers of the world population, science is simply a matter of technology and convenient devices,” he says. “What really would lie at the root of a real [human] transformation would be for people en masse to be able to think scientifically... and by that I only mean rationally: to look at evidence, and to sift it, and to be skeptical about it.”

But where might literature enter this thorny contemporary conversation? McEwan says this juxtaposition of scientific progress and regressive human behavior is an interesting field for writers to examine. “There's a ‘savagery’ [around] that has this ancient quality that might have a far greater impact than any of the great and wonderful [scientific] toys we come up with,” says McEwan. “We seem to be running backwards even as we're thinking of the most extraordinary things.”

Crossing the divide

McEwan would like to see more novelists explore the complex dance between science and human nature—but some would say novelists have been part of the problem. Many believe the Romantic rejection of science still pervades the arts and the humanities, where cultural endeavors are valued as warmly human and emotionally expansive—and science as coldly objectifying and stifling.

David J. Morris, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Nevada, wrote in the Virginia Quarterly Review: “English professors today talk about technology and science fiction the way Victorians talked about sex — only when they are forced to and with a deep sense of [skepticism] about its actual existence.”

In contrast, McEwan treasures science as intellectually enriching and creatively liberating. Scientific themes have often percolated into his novels. Enduring Love (1997)—about a science writer trailed by an irrational stalker—skewered the Romantic literary assumption that intuition is superior to reason. Saturday (2005) riffed on the competing allures of rationalism and emotion, science and literature, violence and virtue. And Nutshell (2016)—narrated from the perspective of an unborn fetus—blended Shakespearean musings with genetics and evolutionary theory. As Daniel Zalewski wrote in The New Yorker: “McEwan's interest in science isn't antiseptic; it sets his mind at play.”

We seem to be running backwards even as we're thinking of the most extraordinary things.Ian McEwan

This interest blossomed when, aged 11, McEwan was sent to Woolverstone Hall, a state boarding school in Suffolk. He was soon reading Iris Murdoch, Graham Greene and T.S. Eliot, but also biochemist Isaac Asimov and Penguin Specials about the brain. He considered studying physics, but a charismatic English teacher ensured he chose English Literature at Sussex University instead. “Discovering poets and novelists for me was blissful, so I didn’t feel any regret. But I don’t think I would have felt any regret the other way either. Maybe. Although I would have been a very indifferent physicist.”

However, McEwan’s lifelong immersion in scientific thought is evident in the scalpel-sharp precision of his language, in the forensic realism of his scenes, and in his unblinking analysis of the human animal. The late Christopher Hitchens called him a “chronicler of the physics of everyday life.” Zadie Smith noted that he is always “refining, improving, engaged by and interested in every set in the process, like a scientist setting up a lab experiment.”

Insights from neuroscience and cognitive psychology have also nourished McEwan’s sense of perception. “I was impressed by Daniel Kahneman’s work on all our cognitive defects, Thinking Fast and Slow,and the list is wonderful, like confirmation bias [how we interpret information in ways that confirm our preconceptions]. Being aware of one's own tendencies—and we're all prone to those biases—is helpful when you are writing a scene between two people who see the world differently.”

(Read: Why do we always get annoyed? Science has irritatingly few answers.)

McEwan has learned more about human nature from William Shakespeare, George Eliot and Jane Austen, and from a lifetime of observation; he just doesn’t comprehend why one wouldn’t welcome lessons from the lab too: “Nearly everything that I end up with in a novel has not got there by conscious research. It is just the flow of my interests that suddenly coalesce.”

Perhaps this is the kind of open-minded interdisciplinary approach which could also help to challenge assumptions and drive collective progress in the wider world? Getting cultural figures to reach a hand across the divide would be a positive start, says McEwan, which is why he often recommends Edward Slingerland’s “wonderful” book What Science Offers The Humanities to friends.

Science / fiction

But it could be argued that novelists who dare to grapple with the broader themes of scientific progress also perform the vital cultural task of helping us to make sense of our changing world. While many writers dismiss science, McEwan regards its progress as a theatre for age-old human dilemmas. His novel Solar (2010), about a boorish physicist, offered a darkly comic dissection of how climate change, however mortally urgent, will have to be solved by flawed human beings. And Machines Like Me (2019) introduced a synthetic human called ‘Adam’ to provoke profound questions about how AI could shatter our assumptions about love, morality and consciousness.

We have moved en masse into a world of technology, whether we like it or not.Ian McEwan

Novels are in many ways an ideal medium for sifting, testing and exploring such grand scientific themes. So if the enduring value of the novel is to provide an imaginative space in which to examine complex questions about humanity and social change, will novelists need to become more scientifically literate?

“I am always hesitant to say what other novelists should be doing, but if you have a commitment to the social realist novel there's no way of avoiding it,” says McEwan. “On the one hand, you could spin great fictions out of fantasy and fabulous tales and other worlds, or go in close and examine intimately the breakup of a marriage. But if you want to get some kind of grip of where we are, how we are, how we got here, where we might go next, and what choices lie before us, you cannot avoid the impact of technology on civilization… The rate of change, the speed with which ideas spread, has become so extraordinary that we would need to have some interest in it. But a lot of my colleagues in the humanities are somehow repelled by it.”

Increasingly it seems, science cannot be ignored. Even in McEwan’s sweeping novel Lessons, which is primarily a whole-life character study, science hums in the background, with Roland Baines’ life affected by events such as Chernobyl and COVID-19. It is at this delicate juncture where science intersects with human lives that McEwan believes science finds its natural place in a contemporary novel. “The novel [in general] is a very personal form and talking in numbers or in machines can often seem to militate against that consideration of what our condition is, so it's an awkward mix,” he admits. “But the real interest for a novel, whether it's science fiction or mainstream fiction, is looking at how technology impacts on civilization first of all—but I also mean [on] private lives.”

Science-fiction writers have, of course, been creatively analysing the possible effects of scientific change on human lives for years— and McEwan is a great admirer of Philip K. Dick, Brian Aldiss, Ursula K. Le Guin and others. Science-leaning novelists, like Cormac McCarthy, Barbara Kingsolver, Margaret Atwood and Amitav Ghosh, have also penned nuanced stories about climate change, pandemics and genomics. But in traditional literary fiction, tussles with science are still rare. McEwan hopes that a new generation will feel more liberated to fearlessly blend the traditional apparatus of the literary novel with an easy mastery of science, as a means of exploring “the kind of ethical dilemmas and social change that new technology will bring.”

The novel and the climate

For contemporary novelists, perhaps the most urgent example of science impacting on human lives is climate change. Bookshops are full of intelligent “cli-fi” novels, themed around climate change or environmental degradation. McEwan has read, and enjoyed, lots of climate fiction. But will this genre trigger real-world change? “The problem is that many quite reasonably illustrate what it would be like to live in a dystopia, a post-civilization breakdown, and I think that just adds to the general numbing,” says McEwan. “At the same time, if you write a novel—and there are quite a few around—in which we come through by some [implausibly] brilliant coming together of minds or political purpose or technological intervention… that too seems somewhat unbelievable.”

The most persuasive model he has identified is the scientifically credible but darkly optimistic work of American novelist Kim Stanley Robinson, who writes about damaged future worlds where a chastened humanity charts a way forward. “Especially in the States, there's a vast amount of scientifically informed [climate fiction] literature. I read a whole swath of them last year.”

And hope—rendered through plausible visions of the future, however dark—may be something which novelists can provide. In his climate change book The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh warned his peers that future generations “may well hold artists and writers to be equally culpable—for the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrats.”

McEwan recently toyed with this genre of darkly optimistic climate fiction in a soon-to-be-published short story, in which he depicts a world shaken by 2-3 limited nuclear exchanges. “It put up so much dust into the upper atmosphere that we had another 25 years to think about climate change because there was an immediate cooling,” he explains. “So I struggled to come up with a sort of ‘nuanced optimism’. But the general drift was that we so horrified ourselves by what we'd done, that there would be massive popular pressure at last to do things.”

Science and the humanities

So if cultural figures have much to gain from embracing scientific insights, or from daring to explore scientific themes, can scientists gain anything from the humanities? “Many scientists think they can gain very little indeed, which is a pity,” says McEwan. “I know many literate scientists who read lots of books and love music and art, but does it help them with their study of the ocean or the upper atmosphere or soil depletion? And their answer is no.”

He suggests that a grounding in literature could help scientists to communicate with the public in a more persuasive manner. Kristin Sainani, a professor of epidemiology at Stanford University, now runs a popular writing course, teaching scientists how to “create strong prose that grabs readers.” And Oxford University mathematician Professor Marcus du Sautoy champions the power of ‘storytelling.’ As Harvard English professor James Engell has written: “Transforming scientific knowledge into solutions requires articulate public engagement, persuasion, and dead serious entertainment—mind and heart fused, a strength of the arts and humanities.”

The humanities are also encouraging complex ethical discussion. Research in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews found that AI researchers welcome the nuanced ethical lessons explored in sci-fi and literary novels, like William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and McEwan’s Machines Like Me. The paper concluded: “Literature provides a site of imaginative thinking through which AI researchers can consider the social and ethical consequences of their work.“ One AI researcher admitted: “Where to push and which direction we should push, and all these things are probably, one way or the other, influenced by literature.”

(Meet the robot that looks almost human.)

The public response

So science and the humanities may have much to learn from each other. But are we ready for a more rationally scientific and intellectually diverse culture? “The matter is a triangle,” insists McEwan. Alongside the artists and the scientists, he says, we must consider “the reader or the consumer of public statements about science or the works of art that might be informed by science.”

But developing a more open-minded and scientifically-literate citizenry—one which can champion rational debate, defend free speech, and imagine alternative futures—may depend on healing any science/humanities rifts in academia. “Our education system [in the UK] has children divided at the age of 16,” says McEwan. “There is no requirement for all citizens, as it were—school children—to do at least an A-Level in something like, let's not call it science, let's just call it critical thinking, or rational debate… So it's the third point of that triangle. The culture has to come around. I don’t think novelists can force it. Or even articulate scientists.”

Oxford University’s vice-chancellor Professor Irene Tracey—a neuroscientist— recently spoke about the importance of encouraging an interdisciplinary approach: “While too many of our humanities students can be bewildered by a simple graph, too many of our scientists are bewildered by clever rhetoric, or simply unaware of the historical context of decisions.” But in progressive schools and universities, a more dynamic culture is emerging. Many institutions now promote an integrated STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) approach. For example, the Egenis Centre for the Study of Life Sciences at the University of Exeter brings together philosophers and genetic scientists for complex interdisciplinary debate.

“This is all dependent on the culture at large becoming more educated in science, and I think that is happening,” adds McEwan. “We're forced into it, to understand even how vaccinations work or how your software works.” He thanks popular science writers, such as cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, and physicist David Deutsch for sharing the great stories of science. Just as we can enjoy music without being musicians, we can enjoy science even if we don’t wear a lab coat. “We have lived through a golden age of science writing,” says McEwan. “There is a popular hunger to read books by well-informed journalists, writers that explore science, or scientists themselves. It started with Jim Watson's The Double Helix (1968) and it's slowly picked up from there.”

Writing the Future

McEwan’s literary career has been shaped by a desire to explore diverse fields of knowledge as a way to illuminate more clearly the wider canvas of life. In the same spirit, he hopes that a triumph of interdisciplinary conversation and rational progress could—still—change the human story for the better.

“It's about understanding what you don't know,” concludes McEwan. “I have always thought that part of the project of education is to make you understand just how ignorant you are and to inculcate some humility in the face of it. The extent of one's own ignorance is quite a discovery. That's true of the humanities too—all the things we haven't read and don’t know. I think people who subscribe to conspiracy theories and simple ideas that explain everything have not yet seen the outer limits of their own knowledge.”