These Monks Saved Their Abbey by Protecting the Earth

Catholic monks in Virginia have reinvigorated their order by vowing to be sustainable.

BERRYVILLE, VA – A tiny community of cloistered monks in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley had two big problems: one theological and the other ecological.

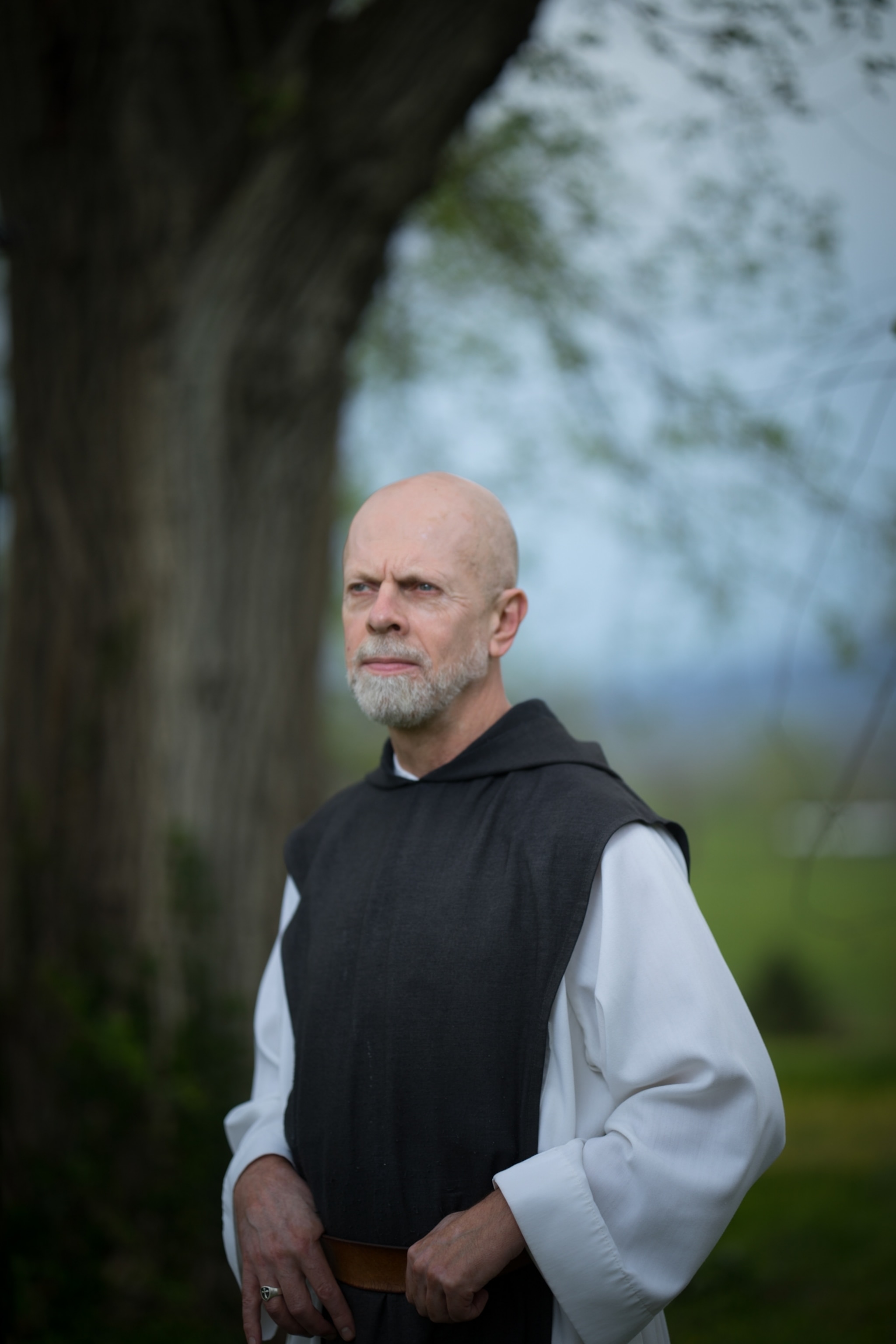

First, the order of Trappist monks had dwindled to ten, from a peak of 68, as members died off and few others joined. It has been an increasingly hard sell to convince men to commit to a life of celibacy, poverty, and obedience—and, in the case of the group more precisely known as the Catholic Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance—silence as well.

The other problem was that Holy Cross Abbey’s 1,200 acres—where monks produce fruitcake and creamed honey and rent land to tenant farmers—were also hurting. The beef cattle being raised in this idyllic spot in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains were trampling the streams feeding into the Shenandoah River and the riverbank itself, sending sediment into the water. The crops raised on the land were treated with harsh pesticides. The community’s buildings were old and leaky. Trash, including inner tubes, was often burned instead of recycled.

Father James Orthmann, 66, who has lived at the monastery since 1977, says that in 2007 the monks started to reassess. “We had to do something,” he says. “If we didn’t we couldn’t be sure we’d be here in another 15 years.”

So Lewis White, at the time a novice at the abbey, reached out to his sister, Annie White, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment. He wanted to learn more about what the monastery could do. “It felt divinely inspired,” she says.

The result was a 14-month project involving six Michigan graduate students that produced a 472-page report measuring just about every aspect of monastery life. The report, “Holy Cross Abbey: Reinhabiting Place,” offered a host of suggestions, from installing low-flow toilets to implementing a compost system. The students looked at economic factors, land use, water systems, waste systems, buildings, industry, and energy use—in short, almost everything affecting daily life at the monastery except the Gregorian chants.

“Trust was a big part of this,” says Andrew Hoffman, professor of sustainable enterprise at Michigan, who directed the project. “To allow strangers to come inside was a big deal, and so we had to present it in a way that was sensitive to who they are.”

That whole journey to sustainability is told movingly in a new one-hour documentary, Saving Place, Saving Grace, aired on PBS stations. Filmmaker Deidra Dain says that when she and co-producer George Patterson started making the film in 2009, Holy Cross had 21 members. “They’re trying to sustain their community as well as the land they live on. It’s the intersection of ecology and theology,” she says.

Opening Up

The cloistered community of monks, who function mostly in silence and rarely venture into the outside community, had a built-in dilemma: keep totally separate from the outside world and risk demise, or open up and seek help outside its borders to sustain its mission.

“After the 1960s and 70s, we’ve been trying to get a more balanced sense of a cloister and privacy in a monastery to preserve an environment of prayer and quiet,” says Father James. “But that does not mean we just cut people out of our lives. Keeping a balance does not mean keeping the door closed.”

The students say they were surprised at how welcoming the monks were, leaving them treats from the bakery and explaining that hospitality has been part of the mission of Cistercians since the group’s beginning.

Former student Kathryn Buckner remembers one of the monks who worked closely with the students: Father Robert Barnes, who died of cancer just after the film was finished. She says, “For somebody who has been in the monastery since he was 19, he was funny and witty and warm and down to earth. Who knew the monks would be so wonderful?”

Since the Michigan report concluded, the monks have started to enact some changes. The most popular and lucrative is the introduction of 80 acres set aside for a natural cemetery. Those buried there—who do not have to be Catholic—can choose to be buried simply in a shroud, in the same way the monks are buried, or in a biodegradable coffin. They can also choose cremation and be scattered in a separate section of the cemetery.

Natural burial there ranges from $4,000 to $8,000, depending on the spot, and cremation burial from $2,000 to $4,000. Since the cemetery opened in 2012, there have been 97 interments and 12 people who have had ashes scattered.

There’s also a new nondenominational, open-air chapel adjacent to the cemetery, topped with a blue heron weathervane, a tribute to the 27 blue heron nests that can be found on the property.

Going Green

But that’s not the only change. The monastery now has a conservation easement, which will protect the land from encroaching developers in this spot about an hour’s drive from Washington, D.C.

In the last five years, Holy Cross has introduced “monastic immersion weekends” in addition to regular silent retreats, so that men and women can get a fuller taste of monastic life. Those weekends always sell out, says Kurt Aschermann, a companion to the abbey. Even the guests for the regular silent retreats are leaving larger donations than in years past, says Father James, which means that the retreats have become more profitable.

A new tenant farmer, Great Country Farms, has introduced organic farming on 200 acres, eschewing pesticides and plowing refuse like corn stalks back into the ground as fertilizer. He’s brought in bees to help pollinate the crops.

The streams where cows once freely roamed are fenced off, as is the Shenandoah riverbed. The grazing area for the cattle is more restricted. Newly planted hardwood trees cover land that was once open grass.

“Even in six months, you could see the difference,” says Father James. “My sense is that the land is healing.”

The monastery’s main chapel, which is expected to open in the next few weeks, has been renovated to become more energy-efficient. And the monk’s fruitcake-producing venture now uses a natural gas-fired convection oven, instead of the leaky old oven that once baked bread for the monastery.

Next up is a plan to rid the property of invasive plant species, like the Ailanthus trees (also commonly called the Tree of Heaven), which is native to China.

All of these changes are fitting for this order, founded in 1098, which counts stewardship of the land as one of its most sacred vows. Earlier vows, Father James says, called Cistercians “lovers of the brethren and of the place.”

Cistercians (more commonly known as Trappists) are best known as being the order that Thomas Merton, author of The Seven Storey Mountain, joined in 1941.

Monks have lived on this spot for 60 years, moving to Virginia after their last home in Rhode Island burned in a 1950 fire. In the 18th century, a young George Washington had surveyed the site, and the original monastery is built around the remains of a farmhouse built around 1784. In 1864, the Civil War Battle of Cool Spring raged here. Some 1,000 men lost their lives.

In many ways, the grounds look as pastoral as they did in those earlier years. There is no sound but chirping birds. Here, the days are measured by four prayer sessions, with the first one starting at 3:30 a.m.

With the youngest monk at 59 (60 on May 1) and the oldest at 90, the monks realize that unless they find new members, time is running out. “I think it’s not too subtle a subtext in the documentary and in conversation that they would love to attract new and younger vocations,” says Michigan’s Hoffman.

Meanwhile, Holy Cross continues with what it’s done for many years: baking fruitcake, tending the land, welcoming guests, and—perhaps most important to the monks—praying.

Says Kathryn Buckner: “They view their purpose in the universe to pray for humanity, to pray for peace and God’s presence and good works in the world. It throws positive energy into the universe for all of us.”

Debra Bruno has written for the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Washingtonian magazine, and many other publications.