Inside the world's biggest pilgrimage for the Virgin Mary

Millions of faithful descend on Mexico City each year, at first by bike or by foot and then often crawling on their knees in honor, to behold Our Virgin of Guadalupe.

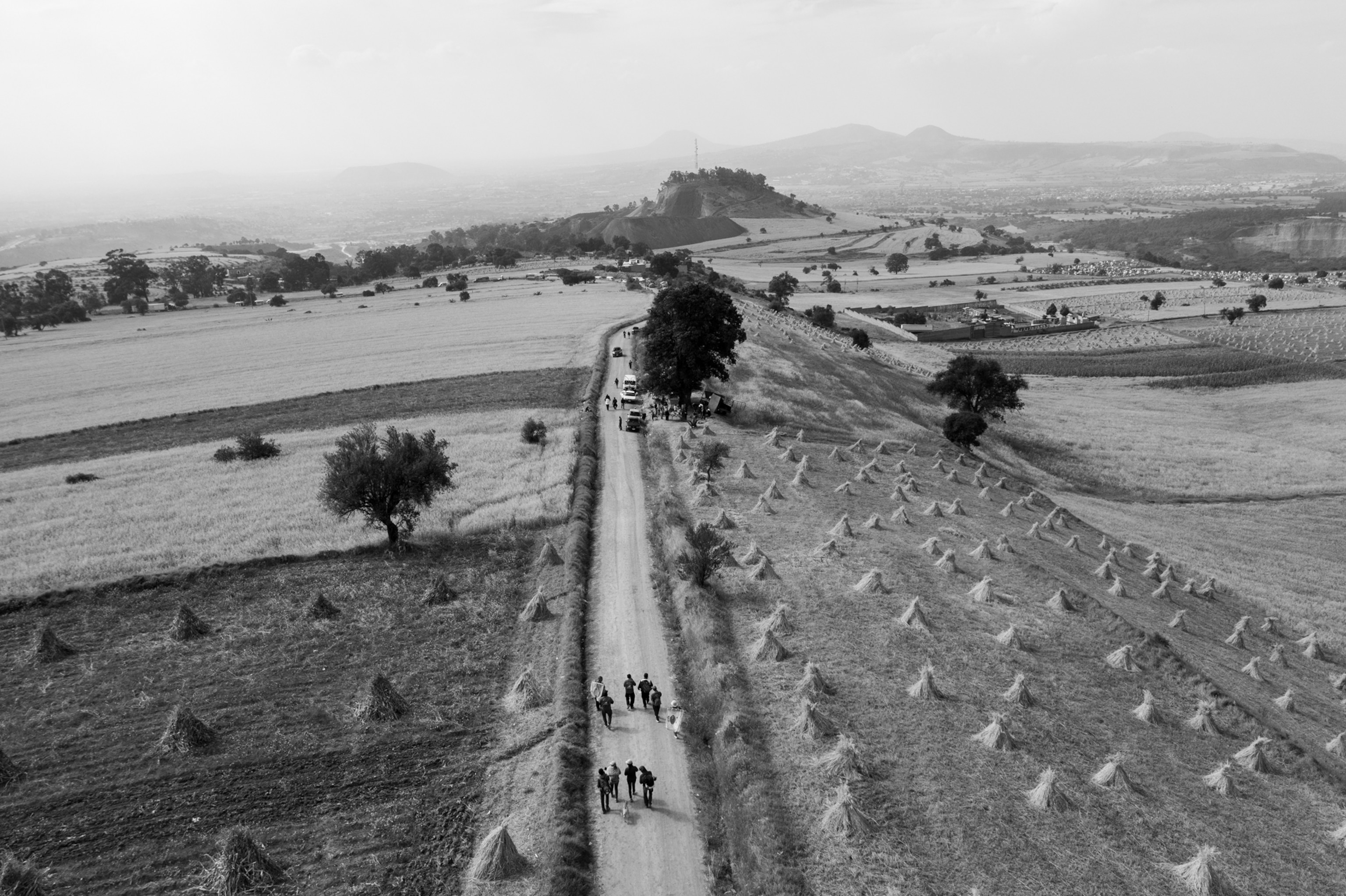

The annual pilgrimage to the world’s most visited shrine to the Virgin Mary stretches from the rural reaches of Mexico to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on a small hill in the capital, ending in a tunnel with a floor that glides slowly along a conveyer belt towards an image of the Madonna. Thirteen million people were expected to make the journey this year for the December 12 feast day, government officials said, many by anachronistic means: on foot through the mountain passes outside of the city, on bikes along backwoods highways, crowded onto the beds of festooned tractor trailers, and on their knees for the final distance.

At the basilica, in a space behind the altar of the circular modern building, the pilgrims funnel onto the moving walkway and tilt their heads up. Hanging on the wall, in a glittering silver and gold frame, is a nearly 500-year-old impression of the Virgin Mary that has become a singular emblem of this deeply Catholic country. That is photographer Kike Arnal’s favorite moment to capture.

“I'm very interested in photographing emotional faces,” Arnal says. “This whole project for me started because of that, because I was deeply moved when I went to the Basilica and saw people looking at the painting of the Virgin, and how they were so touched, how they cried—it was very powerful.”

In a photo series for National Geographic, the Venezuela-born photographer distills the epic-scale movement into intimate scenes that speak to the powerful motivation of faith. Over dozens of miles from the state of Puebla in the east, pilgrims—as young as a few months and well into late life—wear their shoes down until they split and sleep in the open on frosty earth. They carry heavy statues of the dark-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe on their backs and run barefoot on the pavement with torches in hand. But in his documentation, the pilgrimage is also revealed as the social event of the year, the result of extensive planning and coordination among friends, families, and whole communities.

When we first meet, Arnal has been shooting scenes from Llano Grande, a juncture between the mountains that circle the Valley of Mexico. Pilgrims in matching rust orange sweatsuits assemble on bicycles ready to move out in a pack after a lunch of grilled meat tacos sold from smoke-filled tents. “They organize themselves into groups in the towns and in the communities. They rent buses, they rent trucks to transport the food, they bring cooks. It’s very organized. Those on the outside don’t understand how it can work. It works perfectly, synchronized,” Arnal says.

For the faithful, the days of travel into the city are as important as their arrival at the basilica, the same way that a story’s climax can only be reached after an eventful narrative. Arnal began shooting five days ahead of the feast day and walked with pilgrims along several stretches, from their departure in the small city of San Martín Texmelucan to a point in Ixtapaluca, on the edge of Mexico City, where they merge onto a highway still active with whizzing traffic. “It's extremely dangerous, a guillotine. There's something crazy about it, like blind faith,” he says.

To gain the trust of his subjects, Arnal asks about their travels and shares glimpses of his own life, about his family back in Oakland, California. A central question explored in his interviews and photographs is essentially: why?

After the Spanish conquest brought Catholicism to Mexico in the 16th century, church tradition describes a 1531 apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico City that serves as a founding myth of the national blended mestizaje culture. Appearing before Juan Diego, a devout Aztec convert, on Tepeyac Hill, the site of the modern day Mexico City basilica, the Virgin—as the legend goes—requested a chapel be built in her honor. To help Diego convince the local bishop that his message was authentic, she supposedly imprinted an image of herself onto his cloak—the same depiction the church now says hangs in the basilica.

Today, many make the pilgrimage as part of a manda, or vow, to the Virgin, as they ask her for healing or prosperity, or to thank her for her help in overcoming hardship.

Like Sergio Zamarrepa Perez, who on Thursday afternoon pushed his son in a stroller decorated with garlands on the side of the old Puebla-to-Mexico City highway. The four-year-old had been born with a club foot and Zamarrepa and his family have made the walk throughout his treatment as part of a wish for his healing.

“All of this is out of love for him. We feel more at ease. We hope he grows up well and is happy,” Zamarrepa says.

“And because we like it, because these are our customs,” he adds. “We like spending time as a family and sharing it all, seeing how much other people enjoy it, just like us.”