Mystery of 'Alien Megastructure' Star Has Been Cracked

Twinkle, twinkle, Tabby’s Star: Dips in brightness so bizarre. Could it be we’ve found ET? No, not yet! It’s dust we see.

In what will almost certainly be disappointing news for alien aficionados — or at least those hoping for signs of E.T. — scientists have concluded that the deeply erratic twinkling of the most perplexing star in the sky is not the work of aliens, but dust.

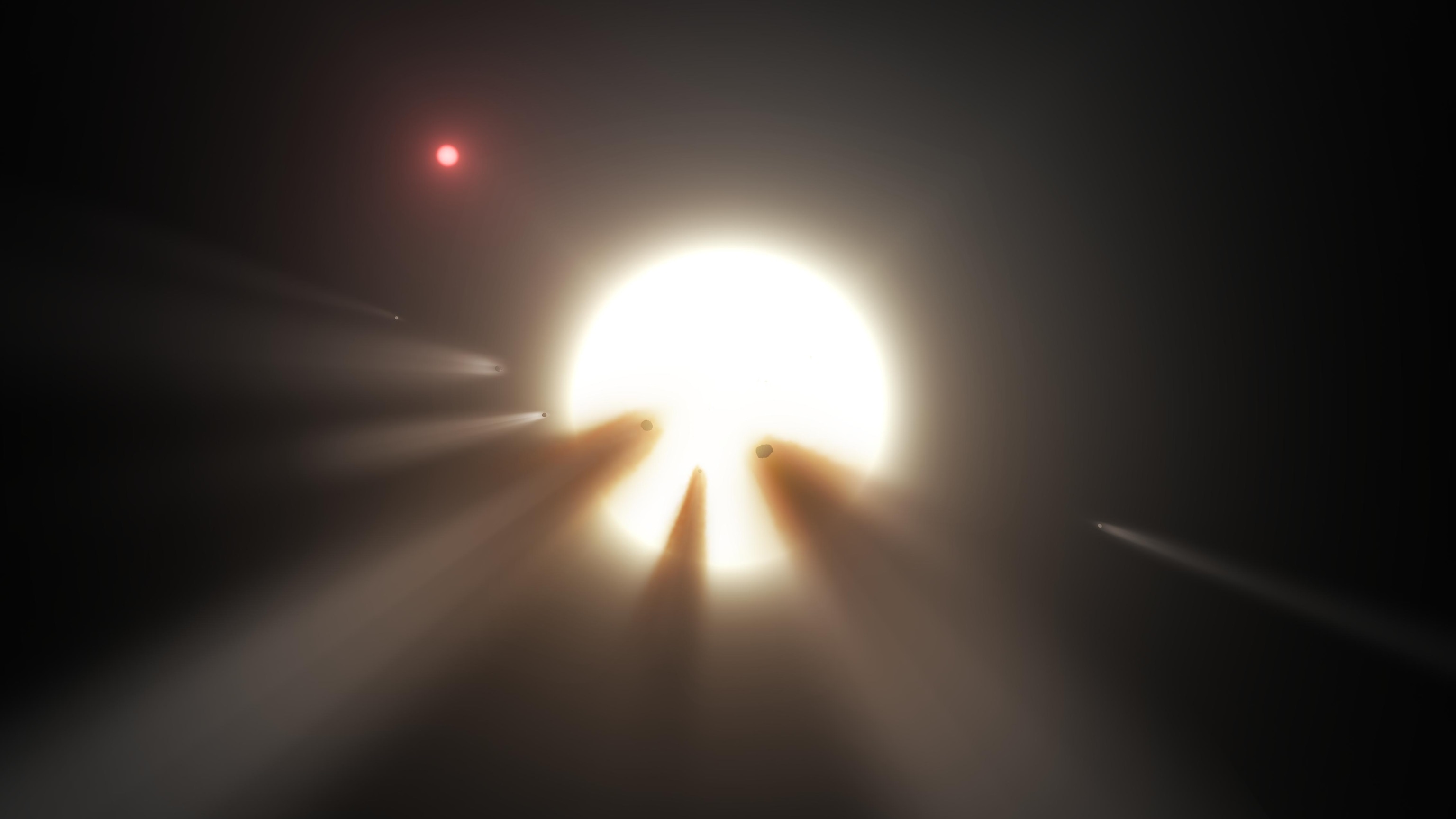

For years, this enigmatic star in the constellation Cygnus baffled astronomers with its seemingly random dips in brightness. Larger and brighter than the sun and nicknamed Tabby’s Star, the stellar weirdo stepped into the spotlight when scientists proposed that alien-built megastructures could be sporadically causing it to darken as they crossed its face.

But new observations suggest the real culprit is dust — perhaps the remains of a planet or moon the star recently destroyed. So, even though plain old dust is considerably less exciting than crafty aliens, there’s still some cosmic sleuthing to be done.

“I love a really good mystery, and I especially love it when all our best ideas just go out the window. It means we get to have more fun,” says Jason Wright of Pennsylvania State University. “The fact that it turned out to be boring old dust, as some would put it, is what everyone expected. But I’m gratified that we still have a nice healthy mystery to crunch on.”

Mystery Blips

The mystery began in 2011, when citizen scientists with the Planet Hunters project were sorting through data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which spotted the signatures of more than 2,300 planets during its four years of primary observations. As planets pass between their stars and Earth, they cause brief and predictable blips in their stars’ light.

But the dips Kepler recorded from Tabby’s star didn’t correspond to anything remotely like a planet’s shadowy fingerprint. Instead, they appeared to be more intense and almost entirely random. Once alerted to the star, formally called KIC 8462852, astronomers couldn’t come up with a reasonable explanation for what they saw.

It just wasn’t behaving like any other star in the sky — and the strange dimming events were only part of the puzzle.

Hypotheses ranged from a swarm of comets orbiting the star, to a dusty debris disk surrounding a black hole between the star and Earth, to material within our own solar system, stellar fluctuations in Tabby’s Star, and finally, alien megastructures.

That idea, published by Wright in 2015, blasted the star into public consciousness, with news story after news story addressing the idea and each new clue fueling yet more coverage.

“I think the connection with SETI is absolutely the reason why the public interest in Tabby’s Star is so great,” says Andrew Siemion, director of the Berkeley SETI Research Center. “We all wonder the same thing when we look up at the night sky: Is there anybody out there?”

Stellar Sleuthing

Motivated by the burgeoning mystery, teams of scientists combed through data spanning more than a century, looking for patterns that could reveal the source of the star’s enigmatic dimming. At first, it seemed as though the dips in starlight happened in roughly 800-day and 1,500-day increments, which might point to orbiting debris (now, scientists are not so sure about that). Other data suggested that independently of the individual blips, the star is consistently getting dimmer (now, scientists are not so sure about that, either).

Astronomers even pointed one of the planet’s most sensitive radio telescopes at the star, hoping to hear murmurs from a civilization intelligent enough to craft structures so large they sometimes block a substantial portion of the star’s light. They heard nothing.

In short, no explanation fit the available observations.

So astronomer Tabetha Boyajian, for whom the star is now informally named, launched a Kickstarter campaign that pulled in more than $100,000 and harnessed the power of a variety of ground-based instruments. Her goal? The catch the star in the act of dimming and get a better look at what might be blocking its light — in real time.

Observations began in March 2016 and continued through December 2017. And in May of last year, Boyajian got lucky: Her star began to dim. Almost immediately, nearly a dozen telescopes on Earth swiveled to stare at it, with scientists furiously collecting data in nearly every wavelength of light. After many months and four distinct dips (named Elsie, Celeste, Scara Brae and Angkor), the star was no longer visible to telescopes in the northern hemisphere.

“It was kind of surreal in a way to watch it happen in real time and be able to do what we have been saying we wanted to do for years: observe it in a dip,” she says.

Now, Boyajian and more than 200 collaborators have analyzed data from the last 22 months and report in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that dust is responsible for the dip — and that alien megastructures definitely are not.

The team knows this because whatever’s causing the dips is not a solid structure.

“If a solid, opaque object like a megastructure was passing in front of the star, it would block out light equally at all colors,” says Boyajian, at Louisiana State University. “This is contrary to what we observe.”

Instead, the dust filters different colors of light differently; put simply, it’s more like looking at starlight through a gossamer fabric than a rigid framework of Quadanium steel.

“Megastructures were always a long shot, but the history of how that came into the picture is valid. It had to be floated out there,” says Pennsylvania State University’s Steinn Sigurdsson, who proposed the idea of a debris-shrouded black hole.

Death Star?

The source of the dust shrouding Tabby’s Star is still a mystery. Its behavior — producing dips of varying intensity and timing — is not what scientists would expect for clumps of material regularly circling the star, which should darken the star at predictable intervals as they swing around in orbit. As well, there are no indications that the dust is warm, which means it must be very far from the star. And the dust grains are incredibly small, much smaller than those in cigarette smoke, and so fine they should be blown outward by the star’s light.

That last observation means there must be some reservoir from which the dust is continually replenished — a hint that perhaps something catastrophic happened, or is still taking place, around Tabby’s Star. That is, if the dust is circumstellar, or surrounding the star.

“If it is circumstellar, we have to understand why a boring F star is doing this and how common it is,” Sigurdsson says. “Could be more than 10 percent of stars to account for us catching one in the act, which is also curious.”

In 2016, Columbia University’s Brian Metzger proposed that perhaps Tabby’s Star had recently pulverized a rocky planet or woebegotten moon that came too close, leaving a dusty, disconnected corpse in orbit. Or perhaps it shredded a swarm of icy objects like those that live beyond Neptune and were pushed in by the next star over, a small red dwarf.

The truth is that, even though scientists now know that Tabby’s Star’s mysterious behavior is not the work of aliens, they’re only marginally closer to explaining the interstellar puzzle.

“A lot of these things are tantalizing hints, and we’re not sure if they’re red herrings or the key to the puzzle,” Wright says. “It kind of feels like a Sherlock Holmes mystery. You’re not sure which clues are going to end up mattering in the end and which are a big waste of time.”