World's Oldest Cave Art Found—And Neanderthals Made It

The findings suggest that Neanderthals and modern humans had the same cognitive abilities.

Long before Picasso, ancient artists in what is now Spain were making creative works of their own, mixing pigments, crafting beads out of seashells, and painting murals on cave walls. The twist? These artistic innovators were probably Neanderthals.

Dated to 65,000 years ago, the cave paintings and shell beads are the first works of art dated to the time of Neanderthals, and they include the oldest cave art ever found. In two new studies, published Thursday in Science and Science Advances, researchers lay out the case that these works of art predate the arrival of modern Homo sapiens to Europe, which means someone else must have created them.

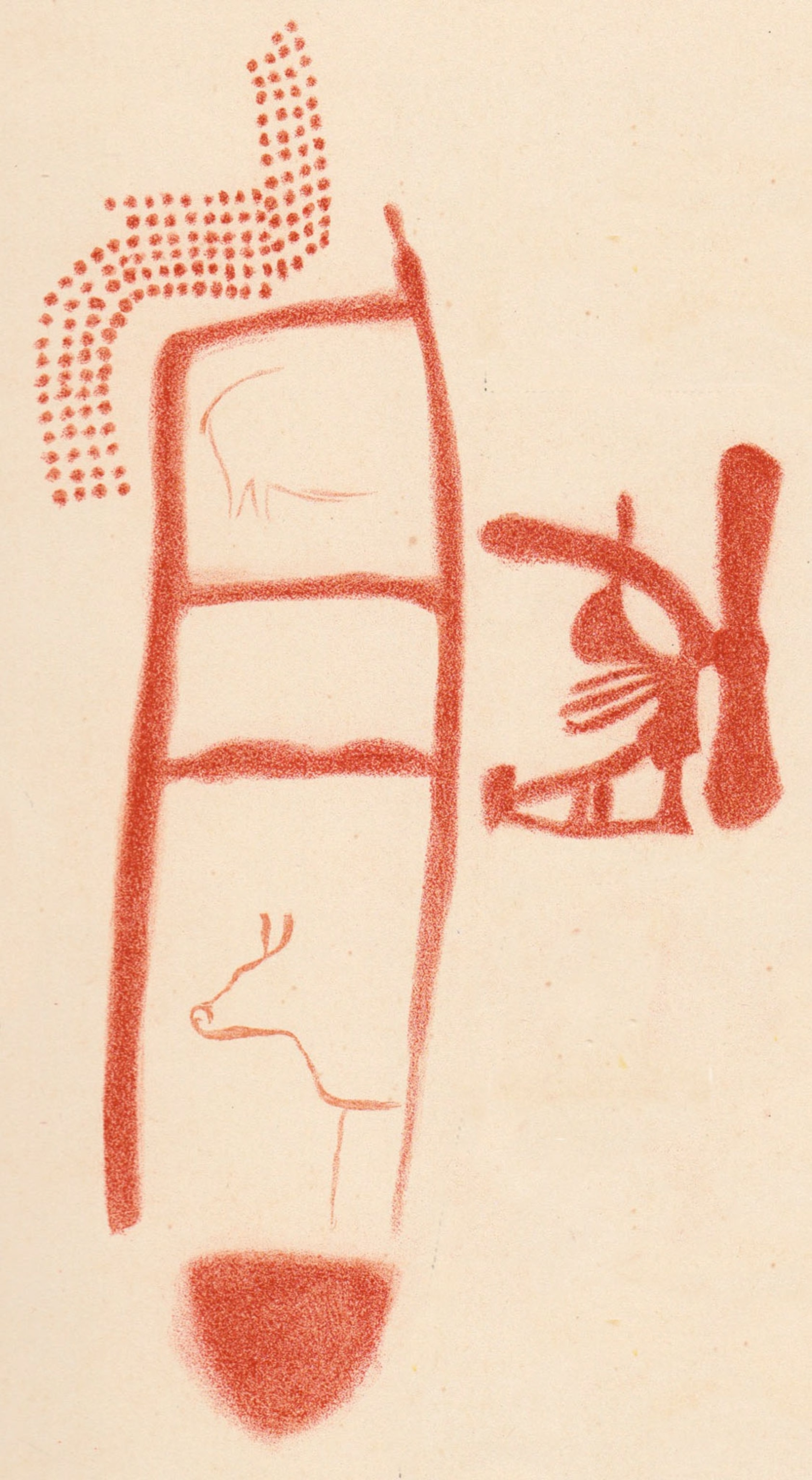

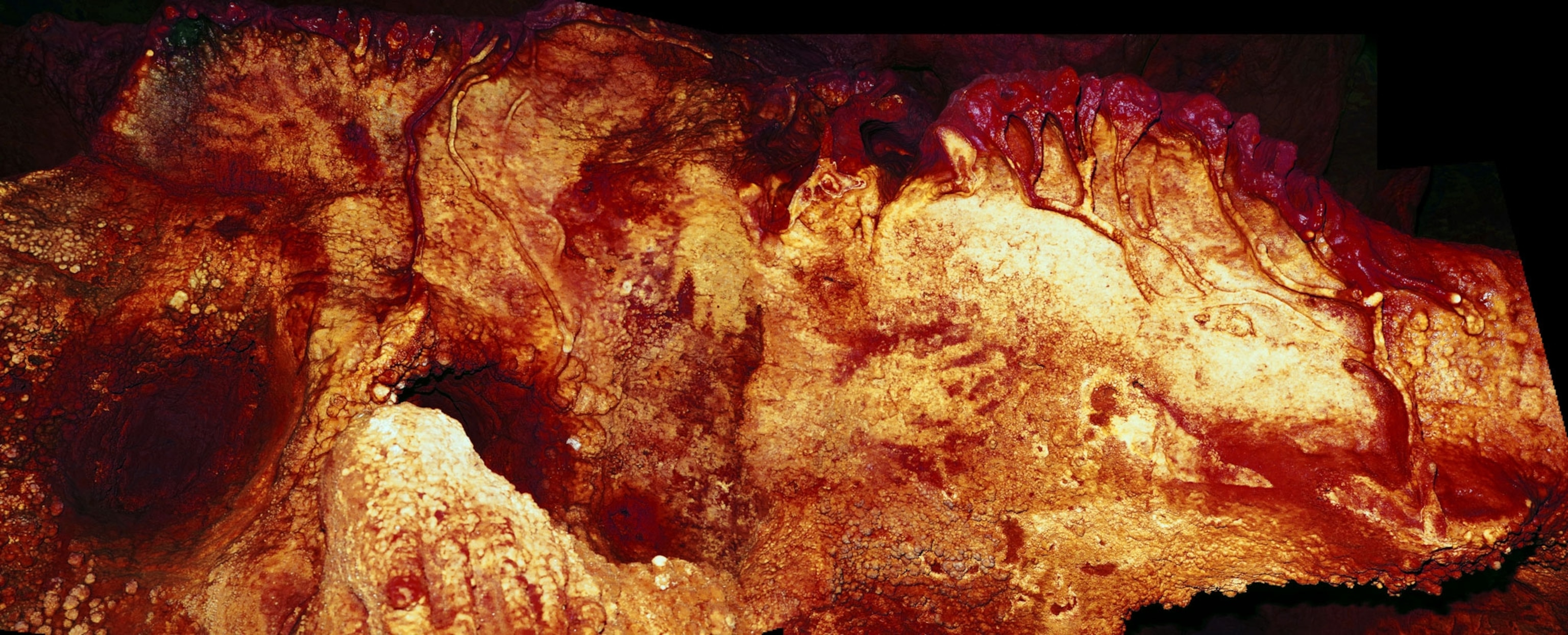

In three caves scattered across Spain, researchers found more than a dozen examples of wall paintings that are more than 65,000 years old. At Cueva de los Aviones, a cave in southeastern Spain, researchers also found perforated seashell beads and pigments that are at least 115,000 years old.

“The Aviones finds are the oldest such objects of personal ornamentation known to this day anywhere in the world,” says study coauthor João Zilhão, a University of Barcelona archaeologist. “They predate by 20 to 40 thousand years anything remotely similar known from the African continent. And they were made by Neanderthals. Do I need to say more?”

The authors argue that, despite their oafish reputations in pop culture, Neanderthals were the cognitive equals of Homo sapiens. If their results hold, the finds imply that the smarts underpinning symbolic art may date back to the common ancestor of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, some 500,000 years ago.

“Neanderthals appear to have had a cultural competence that was shared by modern humans,” says John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who wasn't involved with the study. “They were not dumb brutes, they were recognizably human.”

Knuckle-Draggers No More

In 1856, limestone quarry workers in Germany's Neander Valley found bones that at first seemed to belong to a deformed human. Scientists of the time soon concluded that the large-browed, barrel-chested figure belonged to a distinct hominin species: Homo neanderthalensis.

At the time, Neanderthals were considered more brawn than brains, with one scientist even suggesting that they be classified as Homo stupidus. But since the 1950s, researchers have jettisoned the knuckle-dragging stereotypes. Neanderthals buried their dead with care, crafted stone tools, and used medicinal plants.

Genetic evidence also shows that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred: About two percent of modern European and Asian DNA traces back to Neanderthals. (Find out how much Neanderthal DNA you have by joining our Genographic Project.)

Some researchers had been reluctant, though, to say that Neanderthals could make symbolic art. Based on the evidence at the time, it seemed that early European art didn't flourish until a major wave of modern Homo sapiens arrived on the continent about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Other studies did complicate the narrative. In France, scientists found jewelry made by Neanderthals around 43,000 years ago. In one Spanish cave, similarly ancient charcoal lies alongside cave paintings. But none of these sites substantially predated H. sapiens's arrival, leaving the door open to the idea that Neanderthals merely copied their new, more cultured neighbors.

“If you were to get a hundred representative archaeologists and ask them whether Neanderthals painted caves, 90 percent of them would say no,” says study coauthor Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton. (Learn more about the last Neanderthals in National Geographic magazine.)

It's Elemental

To show that Neanderthals were artists, researchers would need to find art in Europe made well before 50,000 years ago. Pike and Zilhão started brainstorming how to do this in 2003, when they serendipitously met Dirk Hoffmann, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who specializes in dating minerals.

Hoffmann's work relies on the fact that the radioactive element uranium dissolves in water, but the element thorium doesn't. When water percolates through soils into a cave, the waterborne uranium gets trapped in mineral crusts and radioactively decays at a predictable pace into thorium. Since scientists can be confident that no other thorium entered the crusts, measuring the relative amounts of uranium and thorium in minerals can reveal their ages, and thus the ages of any paintings underlying the rock.

To make this measurement, all Hoffmann needs is a bit of rock no bigger than a grain of rice. But getting those samples is no small feat, requiring the use of scalpels mere millimeters away from priceless art.

“One wrong move, and you might remove some pigments from the wall that were there for thousands and thousands of years,” says Hoffmann, the lead author of both studies. “There's this overwhelming feeling you get when you first get in.”

In the three caves with paintings, researchers found that some mineral crusts overlying the paintings were at least 64,800 years old, making the art itself at least that old, if not older. The crusts above the seashells and pigments found in Cueva de los Aviones, however, were at least 115,000 years old—more than doubling the age estimate Zilhão got when he examined the same artifacts in a 2010 study.

Taken together, the cave discovery “shows that this behavior among Neanderthals is not confined to a single period ... it's not just this super-bright group that develops this and just disappears,” says Pike. “It's also completely comparable to what humans were doing in Africa.”

Close Cousins

In light of the two lineages' identical knack for art, the researchers even call into question whether Neanderthals were truly a distinct species, or instead an isolated European subgroup of modern humans.

“The conclusion has to be that Neanderthals were cognitively indistinguishable [from Homo sapiens], and the Neanderthal versus sapiens dichotomy is therefore invalid,” argues Zilhão. “Neanderthals were Homo sapiens, too.”

Other experts, however, recommend caution. Defining ancient art is challenging—and weighing an ancient artist's sophistication is even more fraught, says Margaret Conkey, an emerita professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and an authority on prehistoric cave art. To be even more convincing, she says, future work should focus on explicitly connecting the dating and images with the presence of Neanderthals, whose remains have been found in other Spanish cave systems.

“Does a date alone equal a Neanderthal presence?” she asks. “I have no problem at all that Neanderthals could have been capable of the use of materials like ochre or charcoal to create markings or even images, but it is the usual archaeological challenge: confirming with multiple lines of converging evidence.”

Pike, for one, marvels at the sheer number of avenues future research could explore: “We’ve only just scratched the tip of the iceberg. We could be doing this all our lives.”