A new robotic grabber wants to be the very best, like no sampler ever was. To catch deep-sea creatures is its real test; to release them safely is its cause.

This real-life Poké Ball, unveiled in Science Robotics on Wednesday, is a twelve-sided enclosure slightly smaller than a bowling ball that opens and shuts with a single actuator, keeping it as mechanically simple as possible. The five-armed cage can snap into place in less than a second, safely catching swimming jellyfish and shape-shifting octopuses in water more than 2,000 feet deep.

Called RAD (“Rotary Actuated Dodecahedron”), the device could help scientists catch elusive creatures at the bottom of the ocean, collect data while they’re contained inside, and then let them go unharmed. Its creators hope the apparatus could help make deep-sea biology gentler on the life it studies.

“Life in the deep ocean is slow-moving and old,” said study coauthor and National Geographic explorer Robert Wood, a Harvard University roboticist, in an email. “We want to understand them without destroying them.”

Gotta Catch (and Release) 'em All

Despite more than a century of research, the lower reaches of the sea remain mysterious and starkly understudied. Barely any of Earth's “deep pelagic zone”—the 240 million cubic miles of water more than 660 feet below the surface—has been explored for life. As many as a million unknown species may live within these depths. (Though the massive extinct shark Megalodon isn't one of them.)

Uncovering the secrets of the deep can get messy, however. Scientists have long relied on specialized trawling nets to sample deep-sea life, which not only kill specimens but often shred soft-bodied creatures to tatters. Submersible-mounted samplers can help, but some require extraordinary finesse to operate; others rely on sucking sea creatures into an onboard storage tank and whisking them to the surface, potentially injuring them.

“How do we study an animal at the bottom of the ocean without hurting it, while getting more information than we've ever gotten before?” asks study coauthor David Gruber, a marine biologist at the City University of New York and a National Geographic explorer. “We're trying to use technology to connect with nature, and as scientists, we have to set an example.”

In 2014, Gruber and Wood collaborated to make robotic “squishy fingers” that could collect and handle delicate organisms. But their long-term plan wasn’t to harvest the deep-sea creatures. Instead, they wanted to simply capture them, collect their data, and then release them back into the wild. To do this effectively, though, they'd need some sort of robotic enclosure.

Zhi Ern Teoh, then a postdoctoral researcher in Wood's lab, figured out how to construct such a contraption. At the time, Teoh's focus was on building robots the size of insects, which he accomplished by creating flat components and then folding them into shape with tweezers. It was a painstakingly slow manual process. The key, he thought, would be to automate it.

Soon after, Teoh attended a lecture on the mathematics of origami, which he realized could allow him to make a robot that folds itself into shape. He sketched out a paper mock-up of what became RAD, and to his delight, it folded itself up like a flower blooming in reverse. “That was the 'Eureka moment,'” says Teoh, the study's lead author.

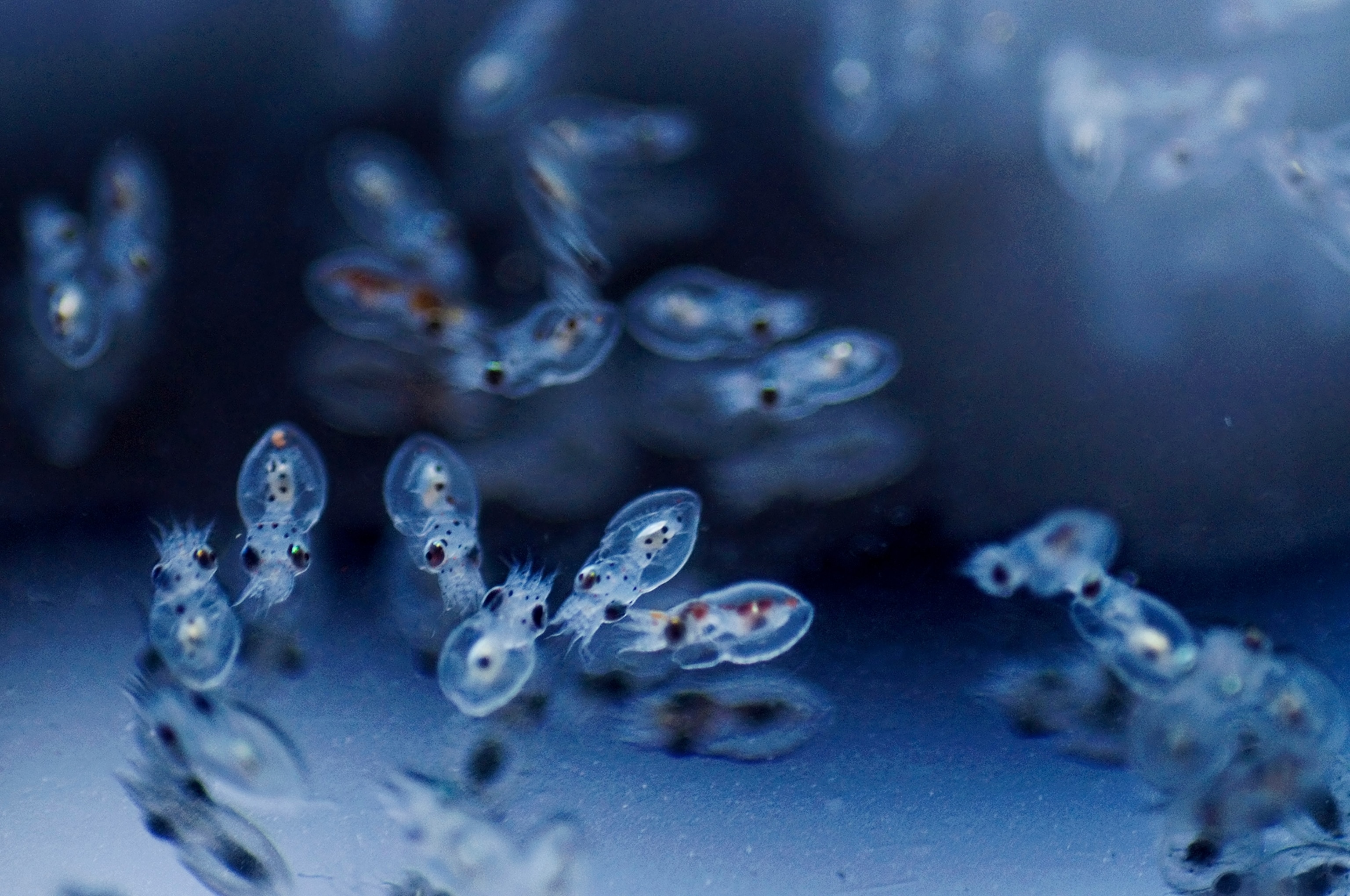

Teoh and his colleagues then built a bigger version designed to capture deep-sea organisms. To ensure that it didn't accidentally lop off any critters' limbs, the team added soft silicone edges to RAD's five arms. They first tested the prototype at Connecticut's Mystic Aquarium, successfully catching and releasing captive jellyfish in a tank.

Researchers then climbed aboard the R/V Rachel Carson, a research ship run by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and put RAD through its paces on a remote-controlled submarine off the coast of California. “It was incredibly satisfying and amazing to see something that you imagine in your head work well,” Teoh says.

A Friendly 'Alien Abduction'

Teoh, now an engineer at Cooper Perkins, says that his invention could have applications beyond the deep blue sea.

“Imagine you want to build 3-dimensional structures at the micro scale; having mechanisms that can fold from 2D to 3D using just one actuator is a pretty attractive option,” he says. “I'm curious to see if there's any applications in space, [such as] portable solar panels or deployable spacecraft.”

Even in its current form, RAD could see some major upgrades. The team wants to install swabs on the sampler's inner walls that would “feel” a confined creature's surface texture and collect its DNA. Cameras within RAD would film a captive animal from multiple angles, enabling scientists to reconstruct its shape in digital form.

Gruber jokingly likens this data collection to a benign alien abduction. “Imagine this jellyfish is down there, and suddenly it's enclosed in this dodecahedron, tickled and DNA-swabbed, and let go,” he says. “Imagine the conversation it has with another jellyfish. It's like a Roswell scene.”