After six years’ work and an epic 204-day 480-million kilometre odyssey it all came down to a single 27-minute burn to insert the UAE Hope probe safely into Mars’ orbit – and vindicate the Arab world’s faith in the mission.

At stake was whether the probe was to skip off the thin Martian atmosphere and into deep space (to be lost forever among the stars), or be smashed into cosmic dust on the distant soil of the Red Planet.

The track record for the nations of Earth exploring Mars is littered with failure, and Mars itself is something of a cosmic graveyard with over 50 per cent of spaceships from Earth failing to safely make planetfall.

Spacecraft propulsion subsystem lead, Ayesha Sharafi says the crew at Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre had to incorporate in their calculations knowledge of the spacecraft’s thrust performance gleaned from minuscule course corrections made on the long flight between planets.

“We performed four manoeuvres in flight using the thrusters, but these were very, very small manoeuvres,” she says. “The longest of them was just 21 seconds, the smallest manoeuvre was less than half a second.”

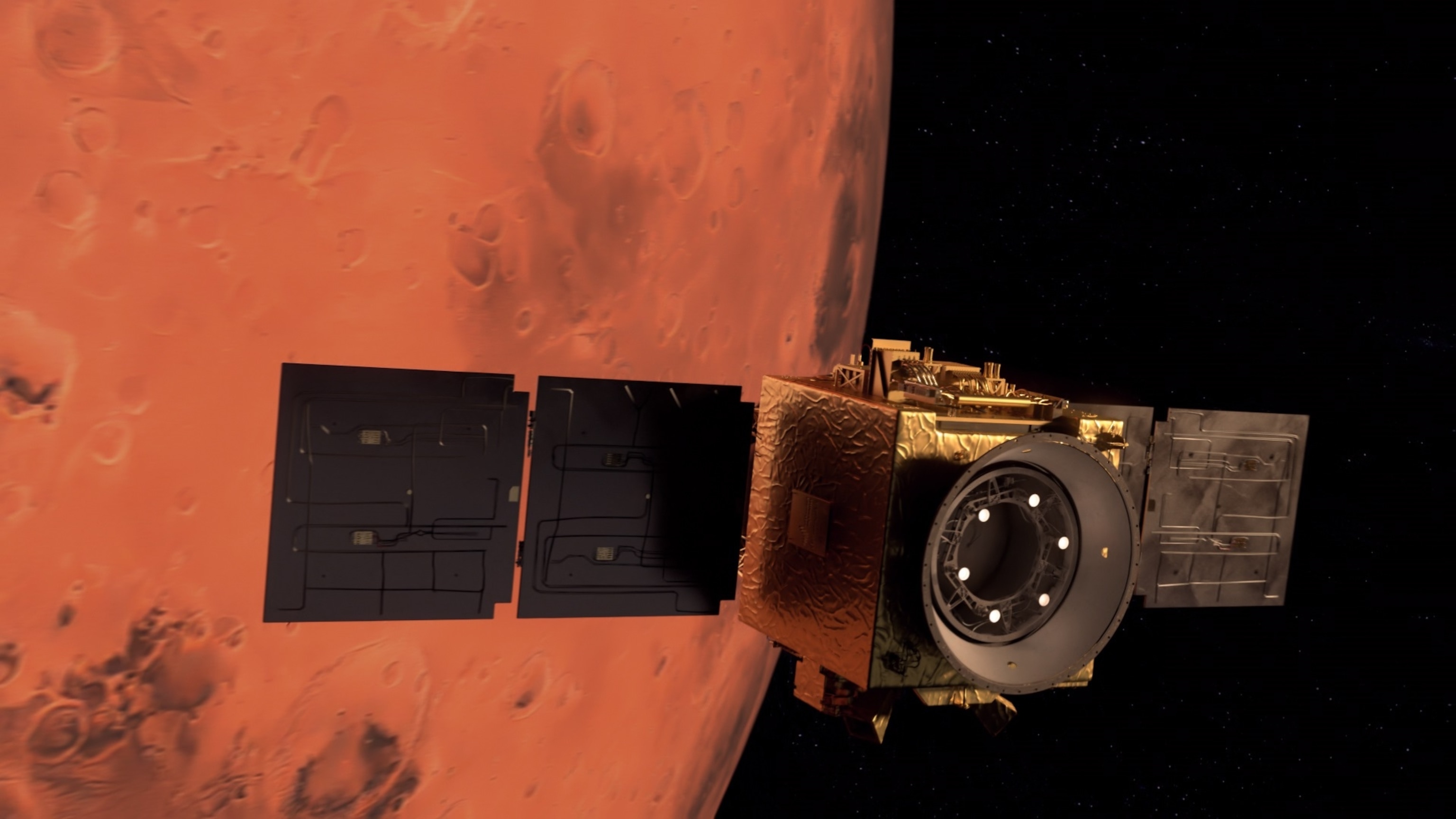

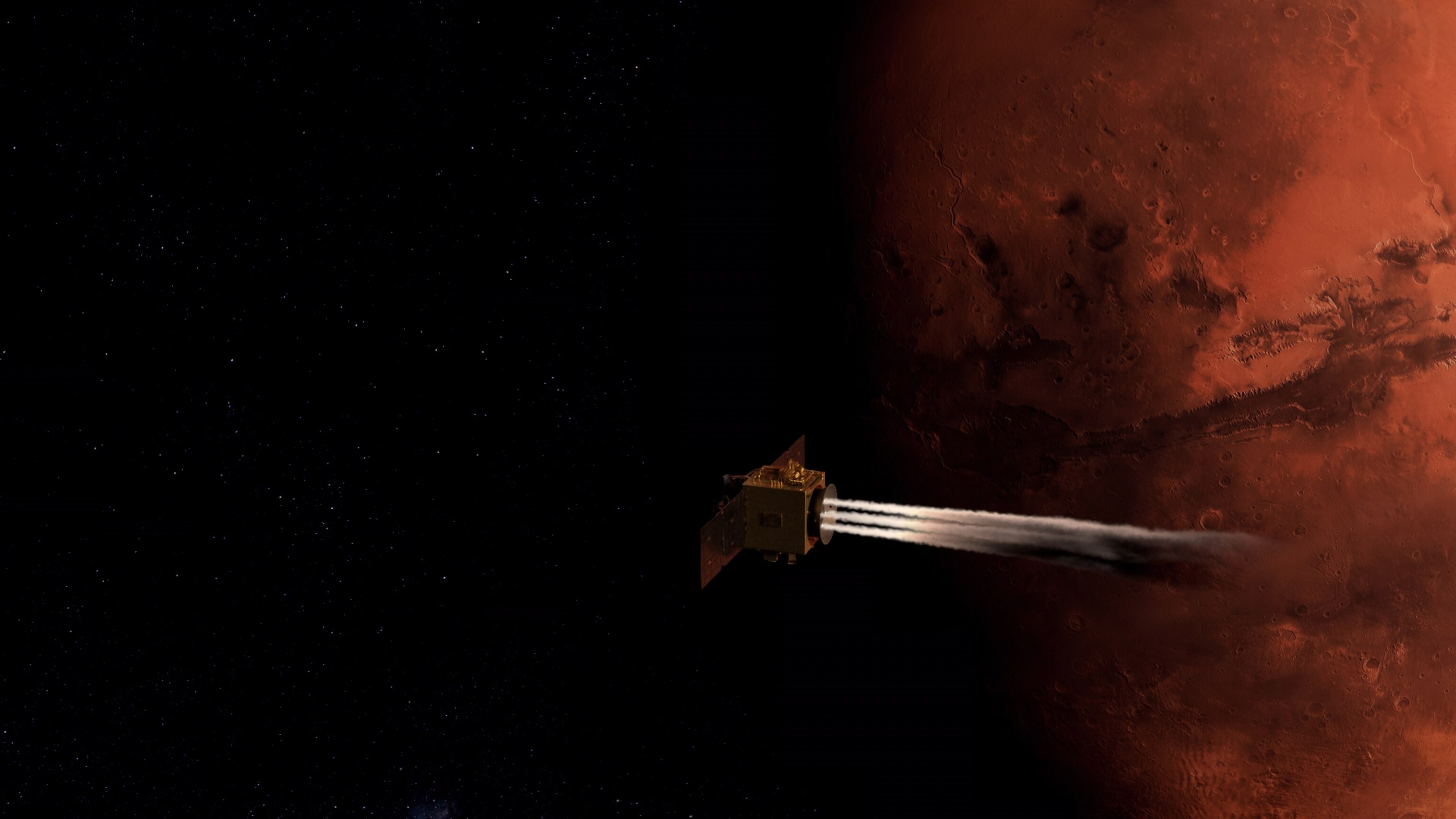

Now the craft had to make a whopping 21-minute burn with its six hydrazine thrusters, slowing its 121,000km/h dead run, to a sedate 18,000km/h and gently place the vehicle in a parking orbit around the red planet where it will spend the next Martian year – the equivalent of two years down here on Earth.

Because of the 11-minute speed-of-light time lag between Dubai and Mars, the burn was preprogramed from orders mission control had beamed to the craft in the days before arrival - but there were early tell-tale signs all was going smoothly on board the 530kg, 2.9 metre probe.

“Five to 10 minutes before burn termination, I knew that we were captured (by Mars’ gravity) because the burn had been going very, very smoothly - more smoothly than I would have ever hoped for.

Once a stable orbit had been confirmed, Sharafi says: “My heart was smiling. It was such a joyous moment,” she said of the February tryst with the red planet.

Project manager of the Emirates Mars Mission, Omran Sharaf says that now Hope is safely in orbit, its real work begins – ground-breaking scientific studies including a look at the Martian atmosphere and how it has changed over time and Mars’ potential for human settlement.

“It is a science mission. But also, it's the first weather satellite on Mars, that's why it's so unique.

“We designed the spacecraft to last for a minimum of four years, and we hope it lasts longer,” says Sharaf.

Equipped with a science package of three sophisticated sensors, Hope will be the first probe to take a detailed look at the Martian atmosphere including investigating how the lower and upper levels of the Martian atmosphere are connected.

“Once we achieve our main mission objectives, the science objectives, that's when we do our initial assessments of the spacecraft and determine what the extended mission will be, what are the new scientific questions we want to conduct, and whether or not our spacecraft is able to support that,” he says.

“But the story doesn't end there, because the novel science that we will do for this mission, and the new discoveries we will make about Mars will benefit humanity as a whole and future missions will be designed and built based on those discoveries.”

The UAE space program is already planning on building on its spectacular Mars success - and the flight of the nation’s first astronaut to the ISS last year - with a Luna rover scheduled to launch in 2024 and preparing Emiratis for their first deep space journeys with the Earth-based Analog Mission.

Rover project leader Hamad Almarzouqi, says the 10kg, 70cm-tall rover will carry instruments designed to help humans better understand the Moon during its 14-day operational lifespan – with a view to manned exploration of our satellite.

Named Rashid after the late Sheik Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the current sheik's father and one of the founders of the UAE, the four-wheel rover will study the properties of Lunar regolith – soil – which coated the spacesuits of the original Apollo astronauts.

“Rashid will trial different materials proposed to protect astronauts, technologies and future robots from the regolith,” he says.

Meanwhile, the UAE Analog Mission is an eight-month mission conducted in a ground-based analogue facility in Moscow to study the effects of isolation and confinement on human psychology, physiology and team dynamics.

Program Director for the Mars 2117 program, Adnan Al Rais says the mission will provide vital data to be used in long-haul deep space missions to Mars and beyond.

“One crew member from UAE along with another five crew members from different parts of the world will be participating in this simulation and analog mission.”

One experiment is investigating the practicality of converting carbon dioxide into glucose for use on long voyages and on future planetary colonies.

Sharaf says the Hope mission and the UAE space program as a whole is a giant step towards creating a new space-focussed ecosystem for the desert nation.

“Nations usually look at big endeavours and refer to them as moonshots, when they want to disrupt something and they want to put big challenges ahead of their youth.

“We have changed that terminology from it being moonshot to it being Mars-shot, which tells you the extreme, that human beings can go to and not to put boundaries or limits on themselves,” he says.

“You really need to push yourself out of the box, you really need to be out of your comfort zone, not just the leadership of the teams working within the leadership but the whole ecosystem needs to be out of the comfort zone.”

Discover more about the UAE’s Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre and their planned space missions on our Reach for the Stars content hub.