An Astronaut's Final Mission: Fight Climate Change and Cancer

Climate scientist Piers Sellers, featured in Leonardo DiCaprio’s new documentary, Before the Flood, discusses his life and time in space.

The new documentary Before the Flood, from National Geographic and Leonardo DiCaprio, takes viewers on a revelatory global tour, showing the real-world impact of climate change from the islands of Palau to the melting glaciers of the Arctic.

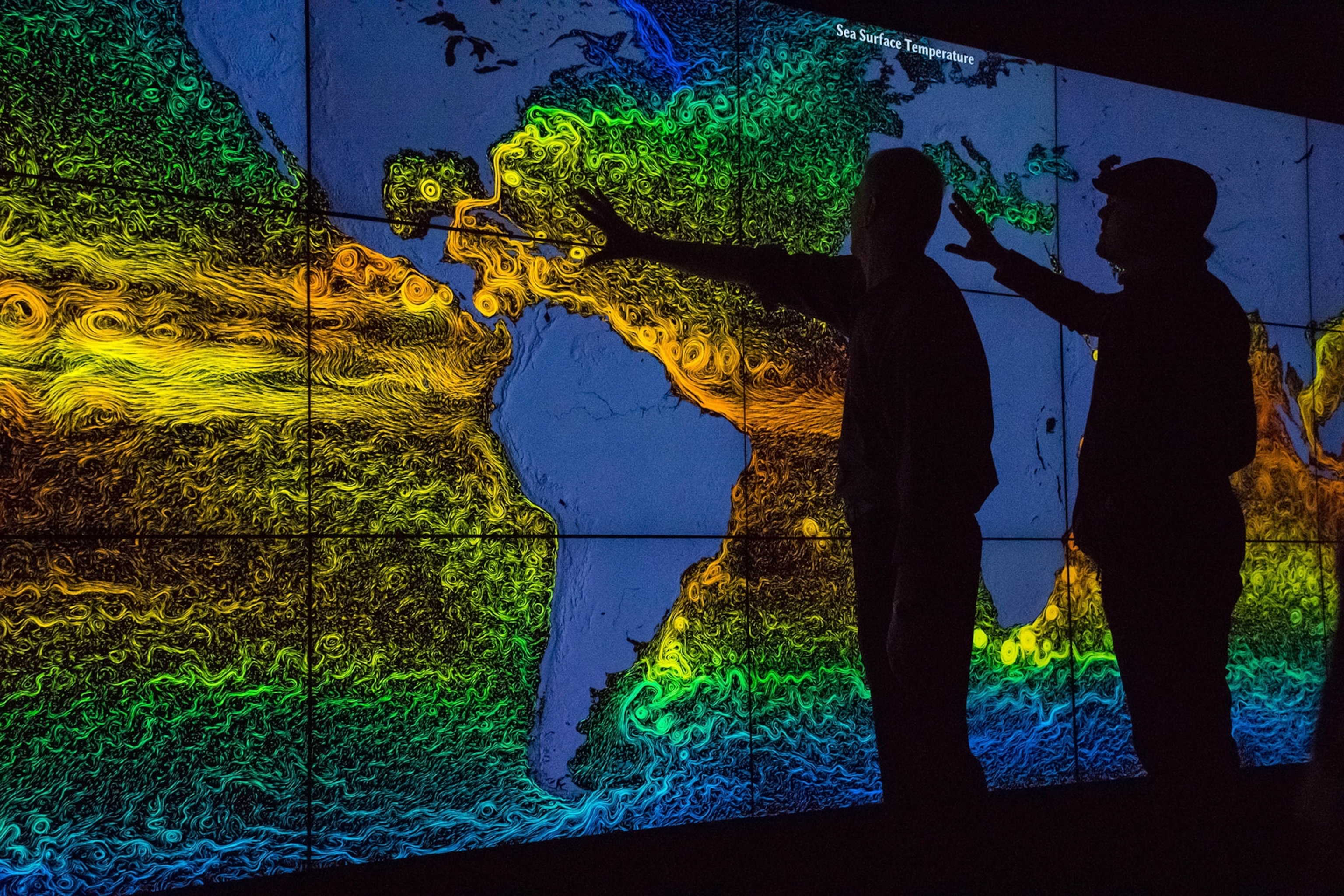

But perhaps the film’s most stirring moments come from an office building in Greenbelt, Maryland, where DiCaprio discusses climate change with Piers Sellers, the acting director of the earth sciences division at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Sellers, a longtime climate scientist, has a unique perspective on the Earth he has long tried to understand: He joined the astronaut corps in 1996, flying on three space shuttle missions to the International Space Station from 2002 to 2010. Now his work has taken on new urgency, as he grapples with stage 4 pancreatic cancer, a diagnosis he announced in January.

We spoke with Sellers one-on-one about his growth as a scientist, the future of humans in space, and how his illness has hardened his resolve to study and fight climate change.

You’re a high-ranking NASA official, a longtime climate scientist, and an astronaut with three missions under your belt. When you were really young, did you ever imagine that your career would take the twists and turns that it has?

Not at all. When I was a little kid, I was fascinated by the manned space program, because they were landing on the moon at the time. I used to cut out all the magazines and collect all the pictures; I thought the whole thing was wonderful. So I thought, Wow, I’d love to be an astronaut. And somehow, I never closed the door on that option.

I talked to my teachers about my desire to be an astronaut, and they said, "Well, you should do science." So off I went into science, and I found out I thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s the fun of finding things out and how things work—all the hidden wheels and cogs in the universe. And when you actually get to do science yourself, that’s a tremendous feeling.

How did you get interested in climate science—and when did you realize the magnitude of the problem posed by climate change?

I started out in ecology and then migrated into climate science. I was really interested in how the biosphere interacts with the atmosphere, so I started modeling that on a computer.

I was a young postdoc when I came here [from the United Kingdom to the United States] in 1982, and I remember reading these early papers, such as [one written by] Manabe and Wetherald in 1975. They were primitive models but a clear warning that we were headed in a dangerous direction. I have to salute them: They had the courage to say that, in spite of the shortcomings, the arrow’s pointing up, and we should pay attention.

What are the key things the public ought to know about climate change?

Here are the facts: The climate is warming. We’ve measured it, from the beginning of the industrial revolution to now. It correlates so well with emissions and with theory, we know within almost an absolute certainty that it’s us who are causing the warming and the CO2 emissions. Because it’s warming, the ice is melting, and because the ice is melting and the oceans are warming, the sea is rising. We observe that, too; it’s on track with the theory.

All these things together convince us that our understanding is correct and give us pretty good confidence to project out into the future. We’re not making this stuff up.

What do you think are the main factors undermining the public’s understanding?

There’s a group of climate deniers who have done a first-class job of spreading disinformation and confusion. We have to deal with a negative propaganda machine that uses many of the same strategies as tobacco [companies]. But scientists should fight the clean fight and explain what uncertainty means. It doesn’t mean that nothing’s going to happen. It just means we’re not sure exactly—exactly—when or how it’s going to happen.

Say you’re standing on a railway track with your friend, and your friend says there’s a train coming. Judging by what you know and see, you say that it’s coming at you between 50 and 70 miles an hour, but you can’t tell exactly how fast it’s coming. Your friend isn’t going to say, “Well, that information’s so uncertain, I can’t act on it, and I’m going to wait until you tell me that it’s going 61 miles per hour before I do anything.”

That’s not the way the world works. The information and predictions aren’t absolutely perfect, but they’re certainly good enough to take action.

As DiCaprio notes in Before the Flood, you seem unflappably optimistic about humankind’s ability to fight climate change. How have you maintained that optimism, despite the scale of the challenge?

It’s a very serious issue and a very serious threat. But if you look through human history, human beings have done a pretty good job of getting off the railway track in time—saving themselves once they realize what’s going on. I’m optimistic that human rationality and common sense will prevail.

Now, we’ve gone from science to policymaking. And the next thing is to energize industry and entrepreneurs to come up with technical solutions: We can’t all turn out the lights and run our cars on chicken manure; that’s not going to cut it. It’s going to take technical innovation to get us out of trouble.

I think that the two-degree world [2 degrees Celsius warming above preindustrial levels] will have some uncomfortable aspects, but it is manageable. People will be able to lead good, happy lives. But I’m not sure if the three-degree world—which is just if we keep plugging away—is manageable. I think the dislocation of water resources and food will create a lot of distress for probably up to two billion people. And that puts stress on the whole world.

To switch tracks a bit: What was it like seeing Earth from space, and how did your climate science background influence your perspective?

This is an absolutely beautiful planet; it’s shatteringly beautiful. I wish I could take everyone else up with me. The curve of the Earth in both directions, this giant ball flying around the sun. It’s very humbling but also uplifting. Emotionally, I think every [astronaut] feels the same.

I had studied the Earth as a system for 20 years before I got up, so I had a lot of intellectual understanding of what I was looking at. But I also saw things as a scientist that adjusted my subjective view of how the world works. I was surprised that the atmosphere was so thin relative to the size of the Earth. I knew it intellectually, but when you see it, you say, “Good God, it’s an onion skin. There’s hardly anything there.” That was remarkable.

You’ve previously expressed an interest in sending people back to the moon. What do you make of the current buzz to send people to Mars?

It’s a very healthy discussion for the country to be having, because these are expensive enterprises. I think that sending human beings to Mars is a very attractive goal, in terms of grasping the public imagination. Scientifically, it’s not that bad, either. If there’s any evidence of past life on Mars, it may be that human exploration is the only way you’re going to find it.

Some of our readers argue that we should spend human-spaceflight funds on other efforts, such as mitigating climate change. As a climate scientist and astronaut, do you think there’s tension between conservation and space exploration?

It’s a good question. Every country has to balance these things and decide how many eggs to put into each basket. The eggs in the NASA basket are pretty small: It’s way less than one percent of the federal budget, but the benefits are a lot more than that. It’s not money down a plug hole.

It’s clear that we’re never going to disband NASA and the National Science Foundation and spend all the money on mitigating climate change. No sensible country would do that. You have to maintain capability for cutting-edge technology and science, because that’s the future.

In a January 2016 New York Times opinion piece, you announced that you have stage 4 pancreatic cancer—a diagnosis you discuss with DiCaprio in Before the Flood. How has it affected your outlook and priorities?

It’s definitely changed the way I’m doing things. This really concentrates the mind, right? Nothing like a short time left to make you parse out what’s important.

The most important things at work for the earth sciences division are to do the maximum extent possible as quickly as possible. The group basically figures out what’s going on [with the planet] and what’s going to happen. I’m doing anything I can to help.

I used to do science in my spare time, but now I spend more time thinking about how to communicate it. That New York Times thing was effective, and that makes me think about how else we can get the word across to people.

Has cancer changed anything about your work-life balance?

What balance? That’s the NASA joke. Work’s very demanding; it always has been. I’m used to that.

I have a fantastic family and a fantastic bunch of friends and colleagues. I probably ought to be spending more time with my family; I’m trying. But a lot of what we’re doing here doesn’t care about those kinds of things. It has to get done, and it has to get done on time. You’ve got 1,300 people here [at NASA Goddard’s earth sciences division], and you don’t want to waste a minute of their time.

You’ve had such a varied life and career. How do you want to be remembered?

Oh, that’s not very important; I’m not a legacy guy. I’m serious.

Gosh. I would like to be remembered as someone who tried hard and was a good colleague, friend, and father. And spouse, too: I’m divorced, but I tried to do my best.

That’s about it. I won’t be remembered as an Einstein, and that’s fine—but I tried really hard, and I had fun. The things I’ve seen, the things that people have allowed me to do, the experiences I’ve had—I’ve had a very rich, rewarding life. Most of it has turned out wonderfully.