Inside NASA’s plan to defeat moon dust. (And why it matters more than you think.)

Moon dust is sharp, corrosive, and potentially fatal. NASA’s new electric force field shield is designed to blast it away.

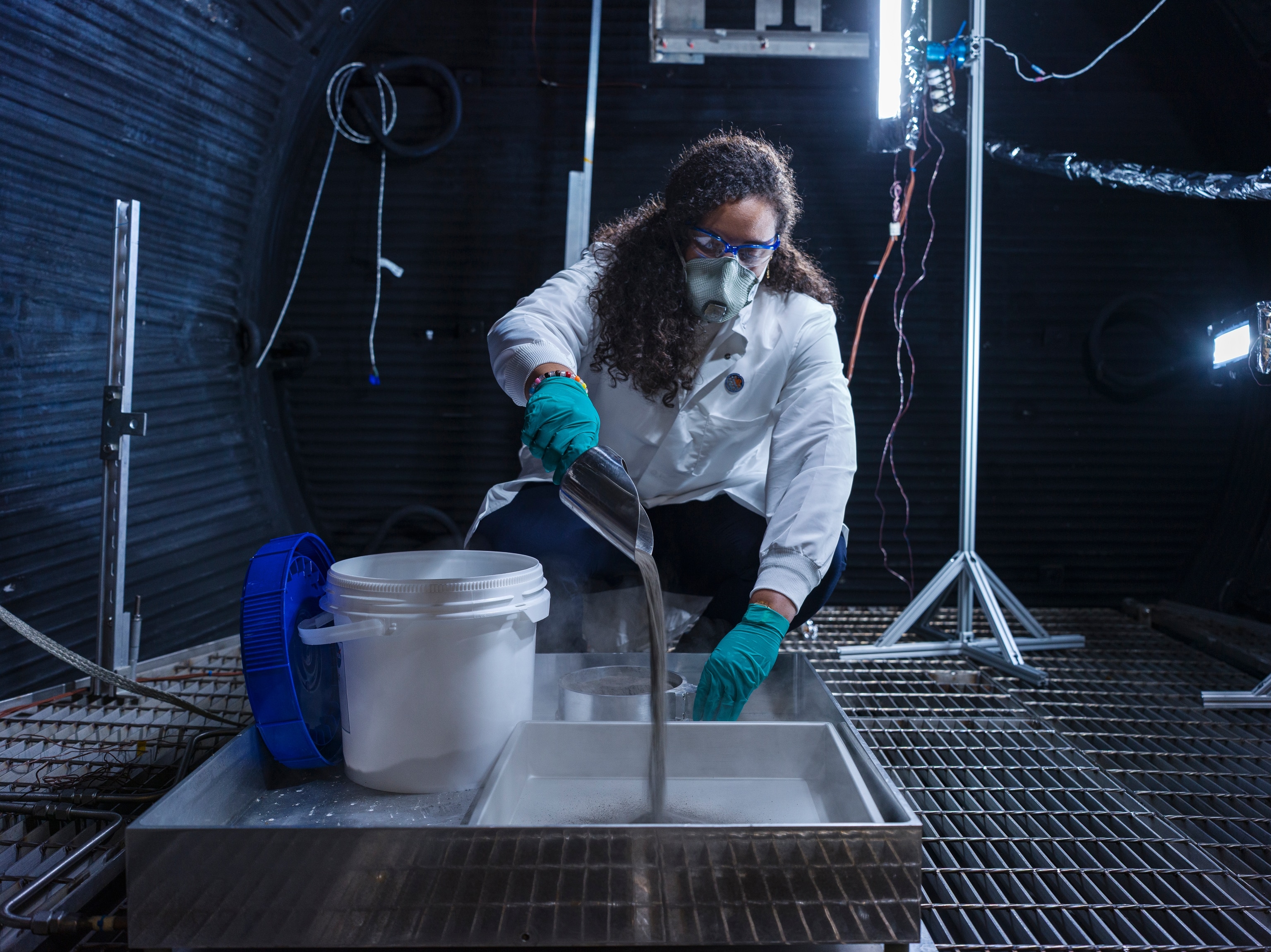

Within NASA’s sprawling Johnson Space Center in Houston are a series of workshops affectionately known as the dirty labs. Inside, through a maze of corridors, cavernous hangars, and claustrophobic rooms, there is dust everywhere: in petri dishes, tubes, boxes, vats, atriums, and crates. In one windowless room filled with storage containers, a large translucent box is pried open, revealing a gray-black miniature desert of remarkably fine powder, and I’m invited to plunge my ungloved hand into it.

It feels like talcum powder but way more adhesive and curiously dense. After swimming through it for a few seconds, I withdraw my hand and find that it’s completely covered. Shaking my hand, and brushing it, doesn’t seem to dislodge any of the powder. The feeling is distinctly alien. And that’s the point: It’s a near-perfect simulation of real-life lunar dust, made from pulverized basalt, a volcanic rock.

The lunar surface is a desert, forged billions of years ago by endless eruptions of lava. Since the moon cooled, its volcanic rocks and glass have been almost constantly smashed to pieces by micrometeorite impacts, producing a haze of free-floating, ultrafine particles of dust.

“It’s very, very sharp. It’s very aggravating and agitating. It gets everywhere,” says Amy Fritz, a dust-mitigation researcher at Johnson Space Center. When lightly agitated or showered by radiation, it becomes electrically charged, meaning that not only can it levitate above the lunar surface; it loves to glue itself onto astronauts. “That’s extremely inconvenient.”

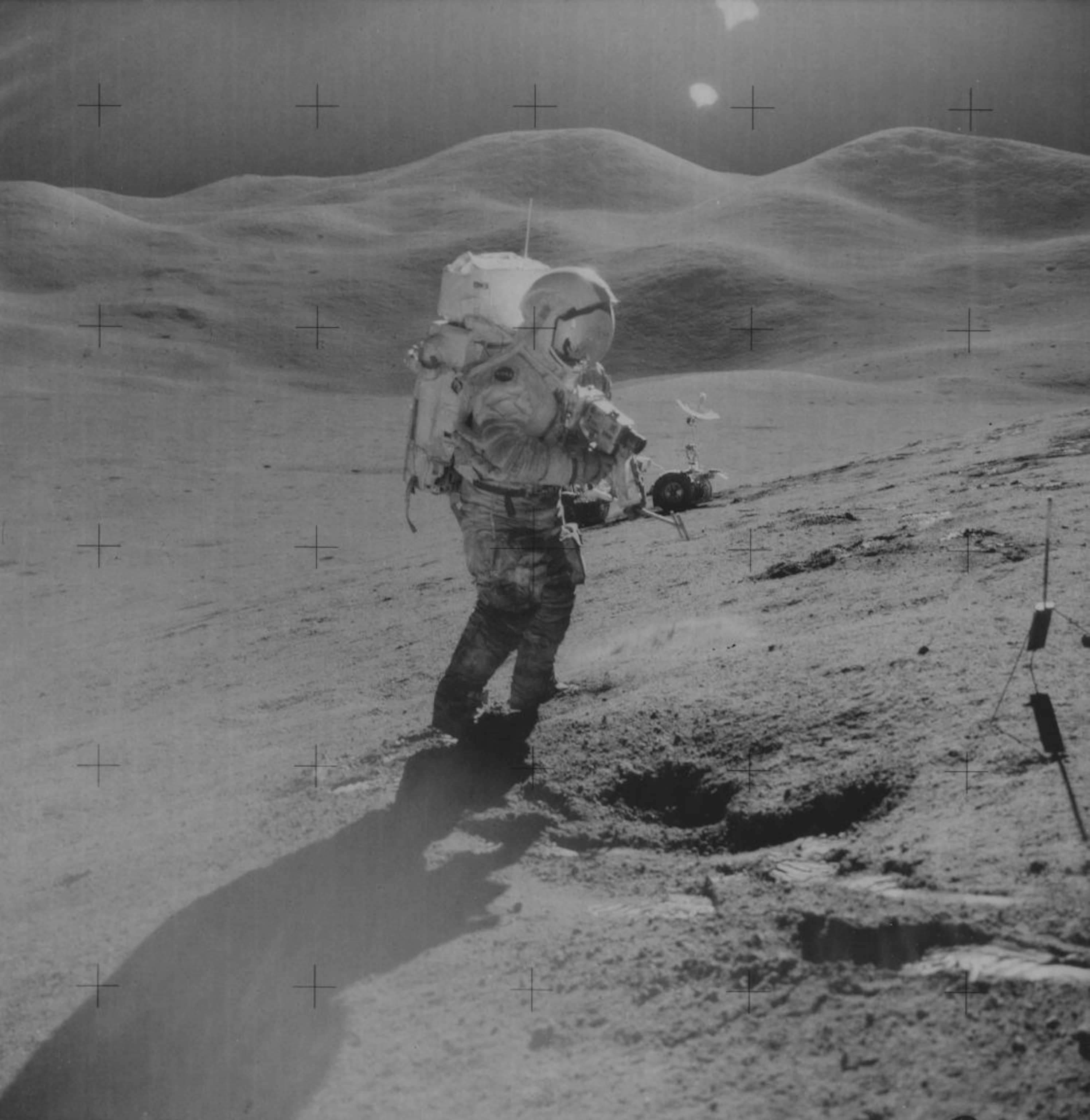

Inconvenient is an understatement. During the Apollo era, lunar dust was inhaled into the astronauts’ lungs, giving them a respiratory condition dubbed lunar hay fever. Everything smelled like burned gunpowder, and they had sneezing fits and persistent nasal congestion. Gene Cernan, the commander of Apollo 17, in particular detested the lunar detritus. “It just sort of inhabits every nook and cranny in the spacecraft and every pore in your skin,” he once remarked.

The dust corroded lifesaving equipment, from vacuum seals to space suit boots. “Their space suits were falling apart after three days,” says Anastasia Ford, a spaceflight technology researcher at Johnson Space Center. The astronauts were given brushes to sweep the dust away, but this proved more problematic than helpful. Not only did the brushes get clogged up, but the act of brushing electrically charged the dust, amplifying its adhesive nature. “How could you clean your cleaning tool?” says Fritz.

In more recent years, those working in the multitude of “dirty labs” at Johnson Space Center—including the experimental Lunar Development and Test Facility—have revealed, in frightening detail, the full extent of the risk lunar dust poses to future missions and astronauts. Scientists have put spaceflight equipment in specialized chambers designed to reproduce the conditions on the moon’s surface—an extremely harsh vacuum with temperatures ranging from 250 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as minus 320 degrees. When the simulated dust I put my hand into is pumped into that environment, equipment gets comprehensively eaten away, whether it’s a camera system or an astronaut’s glove. It’s as if they’re being attacked by microscopic space piranhas.

So it will come as no surprise that working out how to defend space voyagers against lunar dust is one of NASA’s top priorities. With the Artemis program, the space agency is hoping to establish a permanent presence on the lunar south pole. Sending explorers there without any dust protection would prove to be a potentially fatal error: Their solar panels and wires would get chewed up, their next-generation moon rovers would malfunction, and their space suits would break down. At worst, astronauts could die.

Lunar dust really is that precarious. “Pretend to get a whole case of glass bottles. And a sledgehammer. And you smash ’em into bits in a closet. And then you get a leaf blower,” says Charles Buhler, lead scientist of NASA’s Electrostatics and Surface Physics Laboratory. That’s what lunar dust is like. “You have to protect yourself from that.”

Fortunately, NASA is hard at work on a very sci-fi sounding solution to eject the dust from almost any surface.

Fighting dust with electricity

While preparing for the Artemis missions, NASA’s researchers have been conjuring up ways in which lunar dust can be quickly removed from astronauts and their gear. A space-age lint roller “that mimics a gecko’s skin” is currently being tested, says Fritz, as are tools that use gas jets to blast dust off surfaces.

But for now, nothing shows more promise than a protype at the Kennedy Space Center. It’s known as the electrodynamic dust shield, or the EDS. It can be layered on top of, or woven into, pretty much anything. Its electrodes are effectively transparent. And with the flick of a switch, any lunar dust sticking to it is blasted off into space.

The EDS, a transparent dust-defying shield, “has a very long history,” says Buhler. Back in 1967, scientists developed the concept for the electrostatic curtain —an electrically charged veil that used the electrostatic nature of lunar dust against itself. As the curtain passed over positively charged dust particles, its negatively charged surface would attract them, like a fibrous magnet sweeping up iron filings. This concept evolved over the years through collaborations between researchers in the United States and Japan, and eventually found its way into the Kennedy Space Center’s Electrostatics and Surface Physics Laboratory, which was inaugurated in May 2000.

Testing on what would officially become the EDS began back in 2002. A fancy particle-attracting duster was helpful. But what they really needed was a moon dust repeller—a way to make equipment sent to the moon self-cleaning.

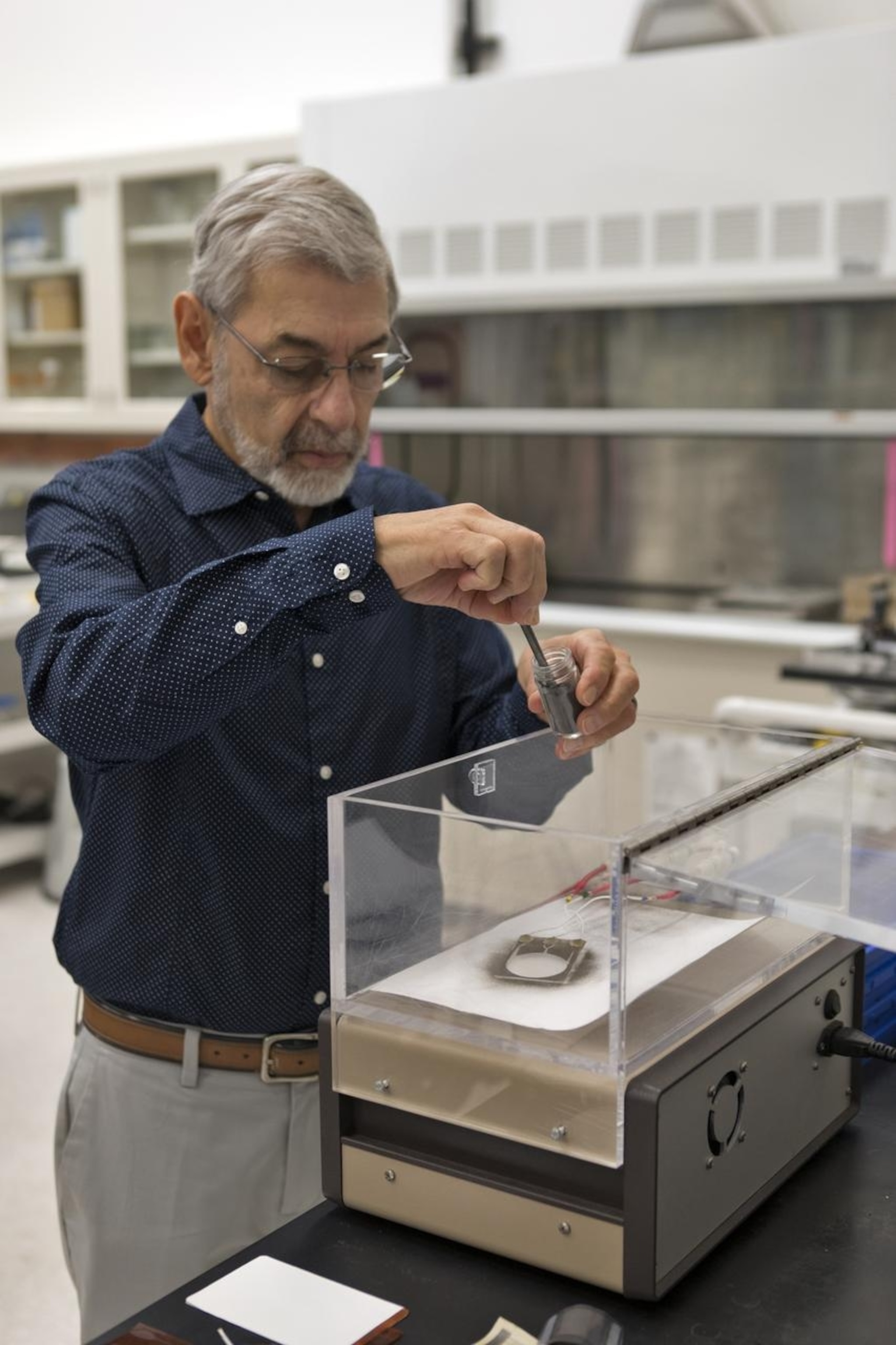

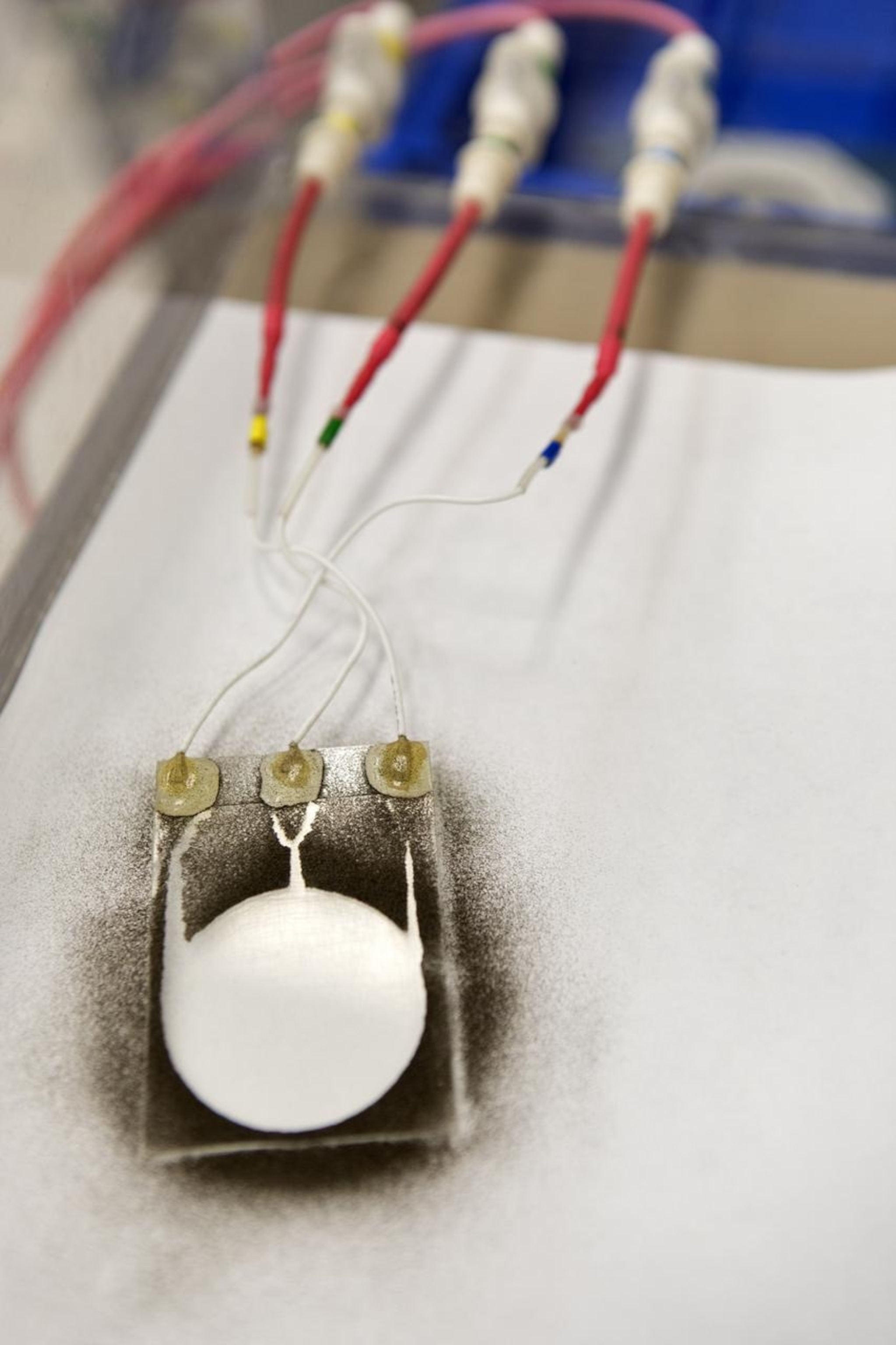

It looks deceptively simple: It’s a two-dimensional array of transparent electrodes connected to a very small power source (like a battery pack or solar-powered plug), and those electrodes are layered onto, or thread into, whatever object or surface you need to remain free of lunar dust. But, as Buhler explains, the science behind it leverages two peculiar forces of nature.

The first is shared with the electrostatic curtain: the Coulomb force. This is a measure of the attraction or repulsion between two electrically charged particles. For the EDS to work, the dust particles need to have the same type of charge as the EDS electrodes: In other words, a positively charged dust particle will be repelled by a positively charged electrode. If so, then the resulting Coulomb force acts to repel the dust from the EDS.

Of course, some dust particles will be negatively charged, and a negative charge is attracted to a positive charge. To overcome this, the EDS’s electrical fields very rapidly switch from positive to negative to ensure both types of dust particles are propelled away from the EDS at essentially the same time.

But as the charge state of the EDS will always be (briefly) attractive to dust that’s oppositely charged, the Coulomb force alone can’t remove all that pernicious lunar dust. That’s why the EDS relies on a second, stranger repellent effect: the dielectrophoretic, or DEP, force.

In physics, a material can be “polarizable.” That means that if you apply an electric field to that material, its own positive charges and negative charges separate over a distance. Imagine a globe, and think of all the positive charges going to the north pole and all the negative charges going to the south pole.

Lunar dust grains are also polarizable. So when you subject them to an electrical field, each grain also gets a positively charged pole and a negatively charged pole.

To take advantage of this, the EDS’s electrical field keeps changing shape, ensuring that the positive part of it sweeps across the positively charged pole in the dust grain, and vice versa. This means both of the dust grain’s electrical poles will experience the repellent push they need for the grain to be swept away from the EDS.

It may sound like magic to those without a background in physics. But the salient point is this: The combination of these two forces should work wonders in removing lunar dust. Tests in vacuum chambers, using lunar simulant dust, show the EDS removing up to 99 percent of the dust from a surface.

But the real promise of the EDS is in its remarkable adaptability. It can act as a shield that’s draped over a surface: You can layer its see-through electrodes onto camera lenses, thermal radiators designed to regulate a spacecraft’s temperature, and solar panels. But it can also be sewn into space suits. “The EDS is embedded into clothing material, through the fabrics,” says Buhler. “It’s incredibly flexible technology. We haven’t found a case where we can’t embed it.”

EDS makes it to the moon

The early Apollo astronauts brought back a trove of lunar rocks—and plenty of sticky lunar dust—for researchers to examine. But as these samples are both rare and scientifically priceless, most of the testing of technology like the EDS is done on the simulated moon dust made by NASA. Conveniently, rocks with almost the same chemistry as those all over the lunar surface can be found on Earth: Volcanoes erupt lavas that cool and solidify into lunar-like rocks all the time. If you pulverize those into near oblivion, you get a very good moon dust replica.

But Buhler’s team even got to try the EDS on some genuine moon dust. “The soils, the Apollo samples we have—we’re able to move the dust pretty easily,” he says.

The EDS has also been tested in space. It first made its way to the International Space Station in 2019. While up there, it was embedded into various types of glass, plastic, and prototype space suit fabrics. The EDS passed its dust-deflecting tests with flying colors.

But making sure the future Artemis astronauts will be protected by the EDS at the lunar south pole is harder. Those dust-filled vacuum chambers are technically superb, but they don’t provide a 100 percent accurate re-creation of the lunar environment. “We can’t get to the full vacuum level of the surface of the moon,” says Ford. “I can’t simulate lunar gravity.”

Lunar dust may behave differently on the real moon—as might the EDS. Putting the EDS in these so-called dirty chambers offers highly valuable testing data, but for Buhler, “the real test is on the moon itself,” he says.

Fortunately, the EDS has already beaten the next Artemis astronauts to their destination.

In recent years, various private, uncrewed spaceflight missions have visited the moon, to varying degrees of success. In January 2025, as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, Firefly Aerospace launched a spaceship toward the lunar surface. Its lander, named Blue Ghost Mission 1, safely touched down on the moon in March, making Firefly the first commercial company to do so.

As part of its scientific instrumentation suite, the lander was equipped with the EDS. And, when the EDS was activated, Buhler’s team could clearly see lunar dust being expunged from a number of glass and thermal radiator surfaces. There is no doubt about it: The EDS works on the actual moon. I asked Buhler what making that discovery was like.

“Oh, you have no idea,” he says, laughing. “Working on something for 20 years, and finally seeing it come to fruition … It’s fantastic. It’s a sigh of relief, more than anything.”

Although the next official use of the EDS–for example, on an upcoming Artemis mission–is not yet set in stone, several industry partners are vying to use NASA’s dust deflector shield on their technology, including the new generation of moon rovers. “There’s a tremendous need for EDS in nearly all of the upcoming missions to both the moon and Mars,” says Buhler.

The EDS won’t be the only tool NASA deploys to protect the Artemis astronauts from a dust-based disaster. But it looks set to be their first line of defense. “It took a while for us to get it to work,” says Buhler. “But,” he adds, with a smile, “we got it to work.”