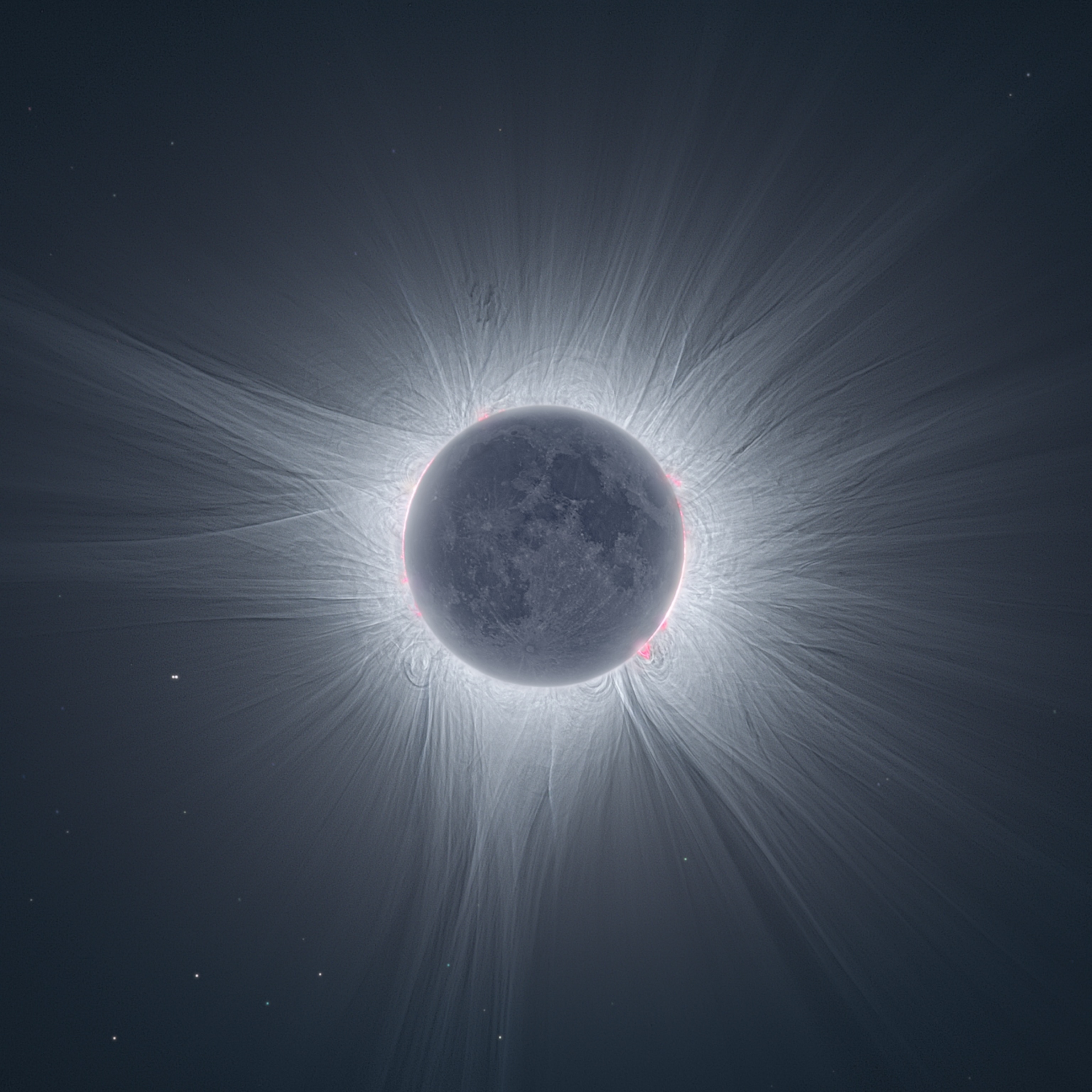

How to See a Space Station Fall From the Sky

A Chinese space station could crash to Earth anytime between now and April 2018. Here’s how to see it with your own eyes.

Six years after it launched, a truck-sized space station is flying out of control on a collision course with Earth—and it could come crashing down almost anytime between now and next April.

The 8.5-ton spacecraft is China’s first space station, named Tiangong-1, which translates to “Heavenly Palace.” Placed in orbit in September 2011, the station was designed to be a test-bed for robotic technologies, and it has seen multiple vehicle rendezvous, dockings, and taikonaut visits during its operational lifetime. The activity lays the groundwork for a more permanent space station the Chinese plan to launch in the near future.

On May 4, 2017, Chinese officials released a report to the United Nations that Tiangong-1 had ceased operating back on March 16, 2016. While it’s no longer in use, the station has maintained its structural integrity.

However, now circling Earth at an average altitude of 200 miles, the station has begun to experience drag as it brushes against the planet’s denser outer atmosphere. Without onboard thrusters to lift it higher, it is losing altitude at about 525 feet a day. At that rate, the station will make a fiery reentry into the atmosphere anytime between October 2017 and April 2018. (Find out about more objects in space that fell to Earth unexpectedly.)

Just this past week, there was a scare in the Middle East when something from space blazed a trail across a city skyline in the United Arab Emirates. But reports indicate that the object was most likely a Russian cargo ship filled with trash that recently left the International Space Station and was intentionally burned up in re-entry.

The precise re-entry date for Tiangong-1 remains unknown at this point, because the density of the upper atmosphere changes depending on solar activity, says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

“We can, at this point, only predict the data to a month or two—January, plus or minus,” he explains. “When it gets to about 24 hours out, we may be able to predict re-entry time to about three hours or so.”

It’s also hard to know where on the planet it will fall. The space station loops around Earth twice every three hours, and its orbit takes it between 42 degrees North latitude and 42 degrees South.

If we don't start cleaning up our act, space could become unusable because of all the shrapnel flying around up there.Jonathan McDowell, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

“So, all we can say is that it will come down somewhere between that latitude limit, and that answer won't change until it actually has come down,” McDowell says.

When it does re-enter the atmosphere, the space station is expected to break apart and there is the small possibility that a few fragments as hefty as 220 pounds will come crashing to Earth. But in their report to the UN, Chinese officials say that the risk of any fragment surviving the fiery trip is quite small.

“The probability of endangering and causing damage to aviation and ground activities is very low,” the Chinese report states.

McDowell agrees. He expects a few small parts will reach the surface, but says that the chances of damage to people or property are very small. He also points out that Tiangong-1 is only a tenth as massive as NASA’s Skylab space station and Russia’s Mir space station. When those stations came down, some debris did make it to the surface, but only in remote unpopulated regions.

With over 50,000 pieces of space junk now being tracked in orbit around the Earth, the real concern for space agencies and satellite companies are in-orbit collisions, McDowell says.

“Space junk is a big and increasing problem, but more for the risk of satellites hitting each other than for things falling out of the sky,” he says. “If we don't start cleaning up our act, space could become unusable because of all the shrapnel flying around up there.”

Instead of being worried, sky-watchers will be able to easily keep tabs on Tinagong-1 as it spirals down into its death dive. The station is visible to the naked eye, and it’s easy to tell the difference between it and a passing airplane: Like many satellites and the ISS, Tiangong-1 looks like an unblinking white light gliding swiftly across the sky.

People living in mid-latitude areas in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere have the best chance of seeing the station, depending on the date. During the second half of October, Southern Hemisphere observers will have clear views of the star-like station in their skies, while Northern Hemisphere sky-watchers will get their chance starting in November. Viewers above 60 degrees latitude will be out of luck, as the station will never rise above your local horizon.

You can find the specific times to look by entering your location into various satellite tracking websites, such as Heavens Above. Click on a specific date and it will even give you a sky chart to help show you where to look.

Will you be able to hunt down Tiangong-1 before its final voyage? The only way to know for sure is to go outside and look up.

Clear skies!

Andrew Fazekas, the Night Sky Guy, is the author of Star Trek: The Official Guide to Our Universe. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, and his website.