The complex debate over how to equitably distribute the different vaccines

One authorized vaccine was less effective in clinical trials, but it has qualities that suit it to being used in vulnerable communities who are likely to be skeptical.

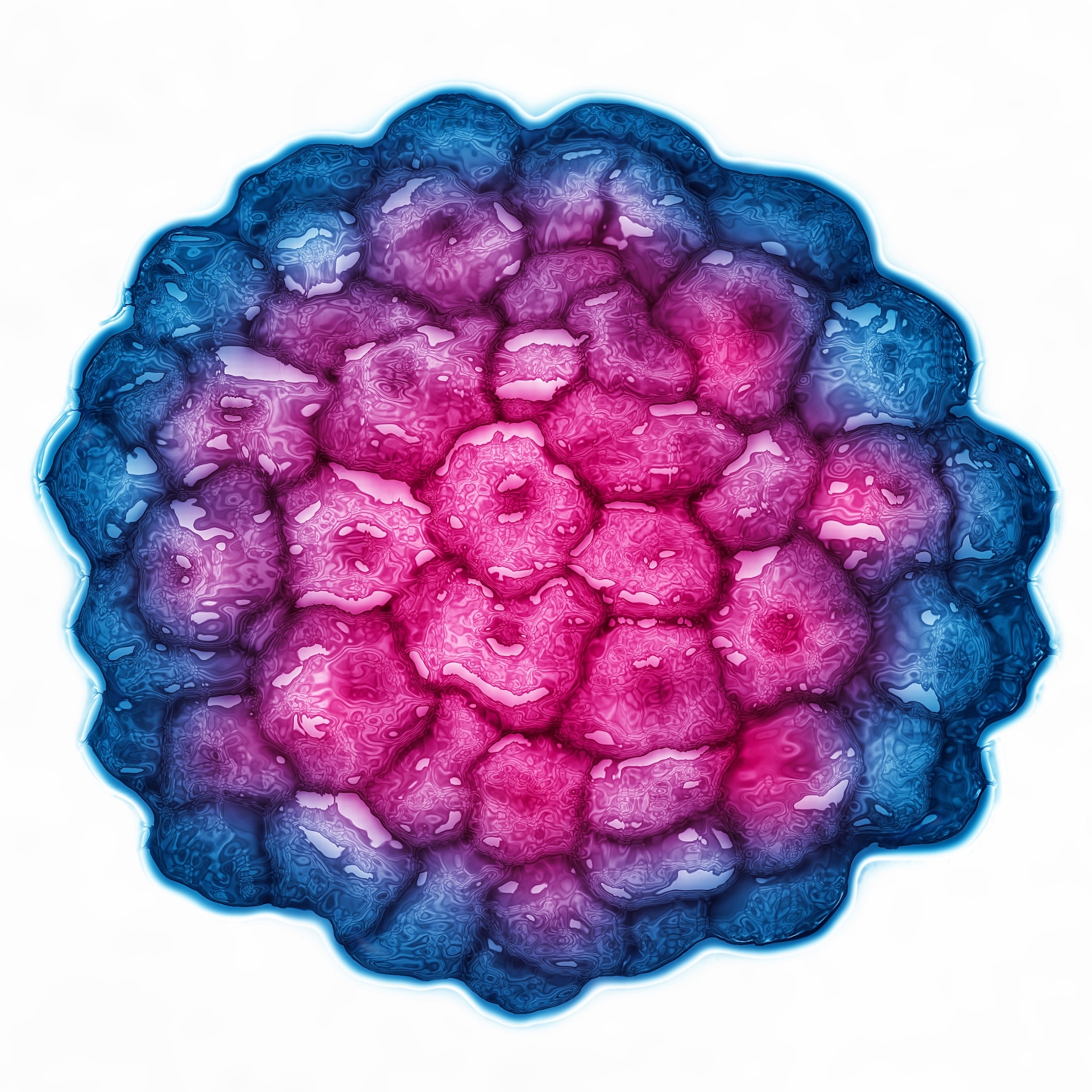

As the first four million doses of Johnson & Johnson’s coronavirus vaccine shipped in March throughout the United States, experts lauded qualities that make it more practical: Unlike its mRNA predecessors, this vaccine doesn’t require ultra-cold storage and needs only a single dose to protect people against serious COVID-19 outcomes—including, most importantly, death.

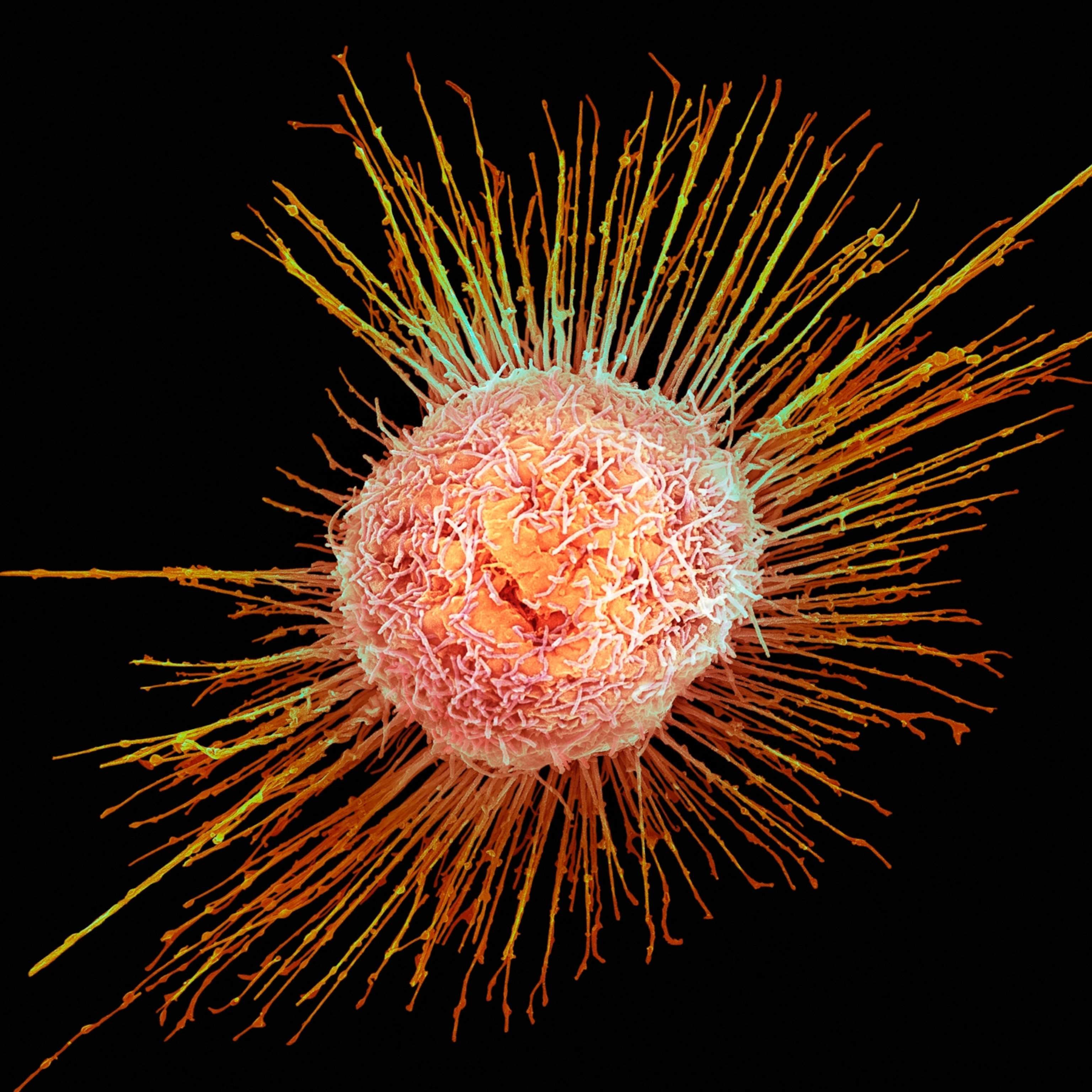

These attributes mean it could be more easily deployed to reach communities that have been left behind as an inequitable vaccine rollout has overly favored white people. But there’s a catch. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine has an overall efficacy lower than the other two vaccines that have been authorized for emergency use in the country. And that fact has raised concerns that marginalized communities—including Black, Latino, and Indigenous people with the highest risk of serious COVID-19 outcomes and a history of medical mistreatment—would be steered toward the vaccine with the lowest level of protection against severe and mild disease.

Infectious disease experts say it’s not that simple: There’s nuance to efficacy rates that must be considered when comparing the available vaccines, and positioning one as inferior could hinder efforts to stamp out a pandemic that has already cost more than 546,000 American lives.

When people draw conclusions from incomplete information, “that’s where things can really go awry,” says Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, chief of the Division of Ethics at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, “particularly in this context, where time is not on our side.”

It’s important to note, experts say, that all three vaccines offer significant protection against COVID-19. Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine may also offer some advantages to marginalized communities. Every expert interviewed for this article agreed on one thing: The best vaccine, they say, is the vaccine people can get today.

But widely distributing a vaccine people are wary of accepting could also have negative impacts, experts acknowledge: It could amplify existing vaccine hesitancy and lower vaccination rates.

“It shouldn’t be surprising that groups who have felt there have been some injustices—in both research and access to care—would feel distrustful of the government or other institutions, in terms of the vaccine delivery,” Lee says. “I understand why there might be some concerns.”

What is efficacy?

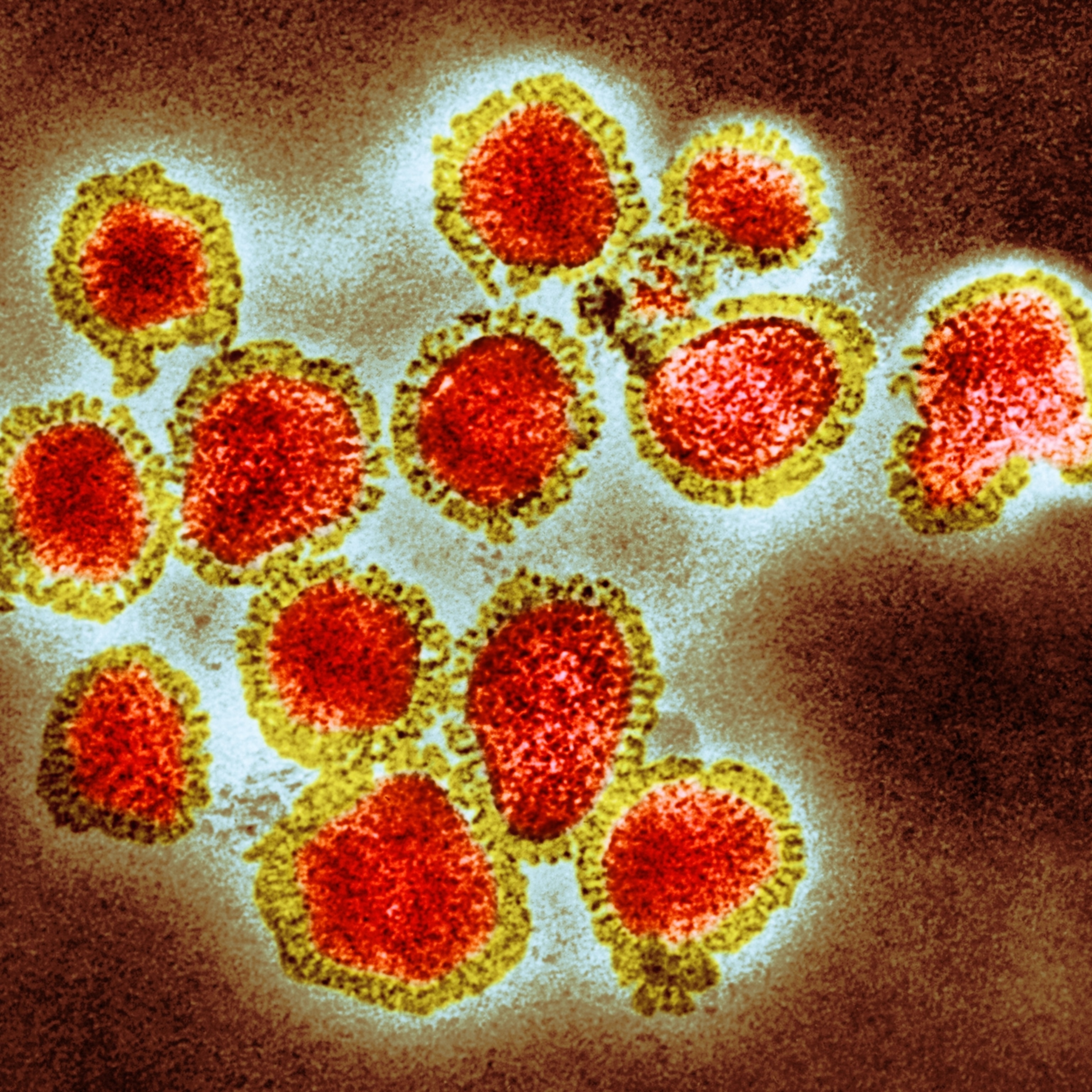

Efficacy is often presented in a single number. For example, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced the emergency use authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, it said the two-shot regimen was 95 percent efficacious in preventing COVID-19.

But zeroing in on a single number misrepresents the data, says Kathleen Neuzil, a physician and director of the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and can fuel incorrect assumptions about what a vaccine can and cannot do.

“Anytime I see a single percentage in a headline, I get anxiety,” she says, “because it’s wrong.”

The vaccines developed to protect against the novel coronavirus were measured in clinical trials against several endpoints, including their ability to protect against mild disease, severe disease, and death. When it comes to protecting against death, all three vaccines are 100 percent efficacious. In other words, not a single clinical trial participant died of COVID-19 after receiving full doses of the vaccines.

Both the Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna vaccines maintained their impressive efficacy of 100 percent in protecting against severe disease, but Johnson & Johnson’s dropped to 85 percent—and it dropped further when including mild COVID-19 disease, reaching 72 percent efficacy in U.S. trial participants.

Pfizer-BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccine was 95 percent efficacious against mild disease; Moderna’s vaccine reached 94 percent efficacy, but dropped to 86 percent for participants 65 and older.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, which had an efficacy of 76 percent of preventing mild illness in U.S. trials, has not yet been authorized for emergency use in this country.

But William Schaffner, a physician and professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, cautions against putting too much weight on the difference between efficacy rates because the vaccines “weren't trialed exactly cheek-to-cheek.”

The trials of the currently authorized vaccines took place at different times, with Pfizer-BioNtech’s and Moderna’s ending before they could include the more easily transmissible COVID-19 variants that were first detected in the U.K. and Brazil. Johnson & Johnson’s trial included those variants. Experts don’t yet know how well the Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna vaccines will fight the variants, though trials are underway.

“When you’re considering the benefits of the vaccine, you’re not just looking at efficacy—you’re looking at the practical application of the vaccine, the delivery of the vaccines,” Chizoba Wonodi, an associate scientist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says. “Vaccines don’t save lives,” she explains. “Vaccinations save lives.”

An uneven vaccine rollout

In an uneven vaccine rollout that has greatly benefited affluent and white people, many have been left behind. That includes people without transportation or childcare, those who work in essential jobs, and Black, brown, and Indigenous people. When it comes to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, some say its “delivery” makes it a logical choice to send to these harder-to-reach marginalized and vulnerable communities.

“Right now, Black people, Latinx people, and Indigenous people are the people who are dying the most from COVID-19, but they have less access to the vaccine,” says Keisha Ray, an assistant professor and bioethicist at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth.

As of March 21, race and ethnicity were known for just 53 percent of people who had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. But the data indicates marginalized groups are underrepresented in the distribution so far. For example, while Latino Americans represent more than 18 percent of the U.S. population, they’ve received just about 9 percent of the doses.

When people come to her with concerns about the vaccines, Ray encourages them to take the vaccine that’s available to them. But while vaccine hesitancy is part of the problem, Ray says, it’s not the entire story. For these populations, “it’s not so much hesitancy as it is access,” she says, or lack thereof. Many Black and Latino Americans often lack necessities for vaccine access: transportation, Internet, paid time-off, and childcare. “All these things are difficult for people of color, who tend to work low-income jobs, who don’t have paid time-off,” Ray says.

Unlike its predecessors, which require ultra-cold storage, Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine needs to be stored only at refrigerator temperatures, making it accessible for hospitals and pharmacies that don’t have ultra-cold freezers and ideal for mobile vaccination efforts. If authorized for emergency use, the AstraZeneca vaccine would share this advantage: It too can be stored in a refrigerator for up to six months. So far, it’s been available outside the U.S., and has been critical to the World Health Organization’s campaign to vaccinate poor and middle-income countries.

While Pfizer-BioNtech’s and Moderna’s vaccines require a two-dose regimen, Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine requires only a single dose. This is a boon for people unable to take time off work, find childcare, or pay to park at a large medical facility, Ray says. And she adds that it also “lowers the risk of missing a second dose” for these groups.

Nir Eyal, founder of the Center for Population-Level Bioethics at Rutgers University, says the Johnson & Johnson vaccine could be especially useful for transient populations, such as some homeless people, who might not be in the same place when it’s time for their second shot.

All three COVID-19 vaccines share similar side effects: People may experience pain, redness, and swelling in their arms after injection, as well as fever, headache, chills, nausea, or tiredness. However, side effects can be more severe after the second dose of Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna’s vaccines—and on rare occasions, both have caused allergic reactions.

Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine did not cause allergic reactions in its clinical trials. Even so, some people still have concerns about this vaccine.

Ray, who is Black, understands why marginalized communities might be reluctant to embrace a vaccine that at first glance appears inferior but at the same time is being promoted by the medical community. “Black people, Latinx people, and Indigenous people have a horrible relationship with medicine and public health,” she says. “We’ve been experimented on. We’ve been tested on. We’ve been lied to. We’ve been misled.”

Those same communities often face the most severe COVID-19 outcomes: Black and Hispanic Americans are about three times more likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19 and about two times more likely to die from the disease than white Americans, according to data from the CDC. These same groups are overrepresented in jobs that put them on the frontlines of COVID-19 risk, including essential jobs such as grocery store employees and healthcare workers.

If Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine is widely available in these communities, “then that does look a little suspicious, as if people of color are sort of an afterthought,” Ray says.

Building trust

It’s unclear if current supplies will allow people or states to pick and choose which vaccines they accept and distribute. However, some policy makers may not accept shipments of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine; Detroit’s mayor recently spoke out against receiving the latest vaccines, saying the other vaccines are the “best” options for the city’s residents. (He later issued a statement saying that he had “full confidence” in Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine.) Only four million doses have been shipped, and it’s unlikely more will be distributed until April.

In the meantime, “we need to start creating spaces where we can promote dialogue and build trust,” says Claudia R. Sotomayor, bioethicist and assistant professor of internal medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center. Without it, “it’s difficult to move forward.”

Policy makers and healthcare providers can build trust with people who “perceive that they might be getting something inferior” by developing “really good public education as to what these various vaccines are able to do, both for them as individuals and their families and communities,” Lee says. “Transparency, and a real investment in public education about how important it is for folks to be vaccinated—regardless of which one they’re getting—is very, very important.”

Ray says that she has concerns about how “perception of the vaccines among people of color and low-income communities” could affect the country’s journey to herd immunity. And Wonodi worries about what could happen to individuals if they shun a vaccine now for one they might get later.

“People should not wait and say, I will come back in a week’s time,” Wonodi says. “You might get exposed to COVID-19 before you come back, and then you miss the chance to be protected.”

She adds, “We have a lot more information about subtleties that really don't matter. Let’s not blow them out of proportion. The most sensible thing is to protect yourself as soon as you can.”

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to correctly reflect the implications of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine trial efficacy rates.