The Black Death was one of history’s deadliest plagues. Here’s why.

Plague, and the infamous Black Death, spread quickly for centuries, killing millions. Plague still occurs but can be treated with antibiotics.

The Black Death was one of the most infamous pandemic events in history. It spread across Asia and Europe, decimating a third of the continent’s population during the Middle Ages.

The cause was plague, one of the deadliest diseases in human history, second only to smallpox. Plague outbreaks like the Black Death are the most notorious epidemics in history, even inciting fears of the disease’s use as a biological weapon.

Today, cases still pop up sporadically around the world, including in the United States. But it’s no longer as deadly, thanks to antibiotics.

Here’s what you need to know about the disease, including how it spreads, the difference between bubonic and pneumonic plague, the most infamous pandemics in history, and why it’s not all that unusual to see cases today.

(Fast and lethal, the Black Death spread more than a mile per day)

The Black Death and other infamous plagues

Three particularly well-known plague epidemics occurred before the cause was discovered. The first well-documented crisis was the Plague of Justinian, which began in 542 A.D.

Named after the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, the pandemic killed up to 10,000 people a day in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey), according to ancient historians. Modern estimates indicate half of Europe’s population—almost 100 million deaths—was wiped out before it subsided in the 700s.

But arguably the most infamous outbreak was the so-called Black Death, a multi-century pandemic that swept through Asia and Europe. Historians believe it started in China in 1334 and quickly spread along trade routes. By the late 1340s, it had reached Europe via Sicilian ports and ultimately killed an estimated 25 million people.

The Black Death lingered for centuries, particularly in cities. Outbreaks included the Great Plague of London (1665-66), in which 70,000 people died.

(Two of history’s deadliest plagues were linked, with implications for another outbreak)

The cause wasn’t discovered until the most recent global outbreak, which started in China in 1860 and didn’t officially end until 1959. That pandemic caused roughly 10 million deaths. It was brought to North America in the early 1900s by ships and spread to small mammals throughout the U.S.

The high rate of fatality during these pandemics meant that the dead were often buried in quickly dug mass graves. From teeth of these victims, scientists have determined that the strain from the Justinian Plague was related to, but distinct from, other strains.

(Read how modern plague strains descended from a strain that arose during the Black Death pandemic.)

Types of plague

The Black Death was a bubonic plague, the disease’s most common form. The name refers to telltale buboes—painfully swollen lymph nodes—that appear around the groin, armpit, or neck. Skin sores become black, hence its foreboding nickname during the 14th-century pandemic. Initial symptoms of this early stage include vomiting, nausea, and fever.

(Black Death discovery offers rare new look at plague catastrophe)

Pneumonic plague, the most infectious type, is an advanced stage of plague that moves into the lungs. During this stage, the disease is passed directly, person to person, through airborne particles coughed from an infected person’s lungs.

If untreated, bubonic and pneumonic plague can progress to septicemic plague, infecting the bloodstream. If left untreated, pneumonic and septicemic plague kills almost 100 percent of those it infects.

Transmission and symptoms

For hundreds of years, what caused outbreaks remained mysterious, and shrouded in superstitions. But keen observations and advances in microscopes eventually helped unveil the true culprit. In 1894, Alexandre Yersin discovered the cause of the disease, the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

Y. pestis is an extraordinarily virulent, rod-shaped bacterium. Y. pestis disables the immune system of its host by injecting toxins into defense cells, such as macrophages, that are tasked with detecting bacterial infections. Once these cells are knocked out, the bacteria can multiply unhindered.

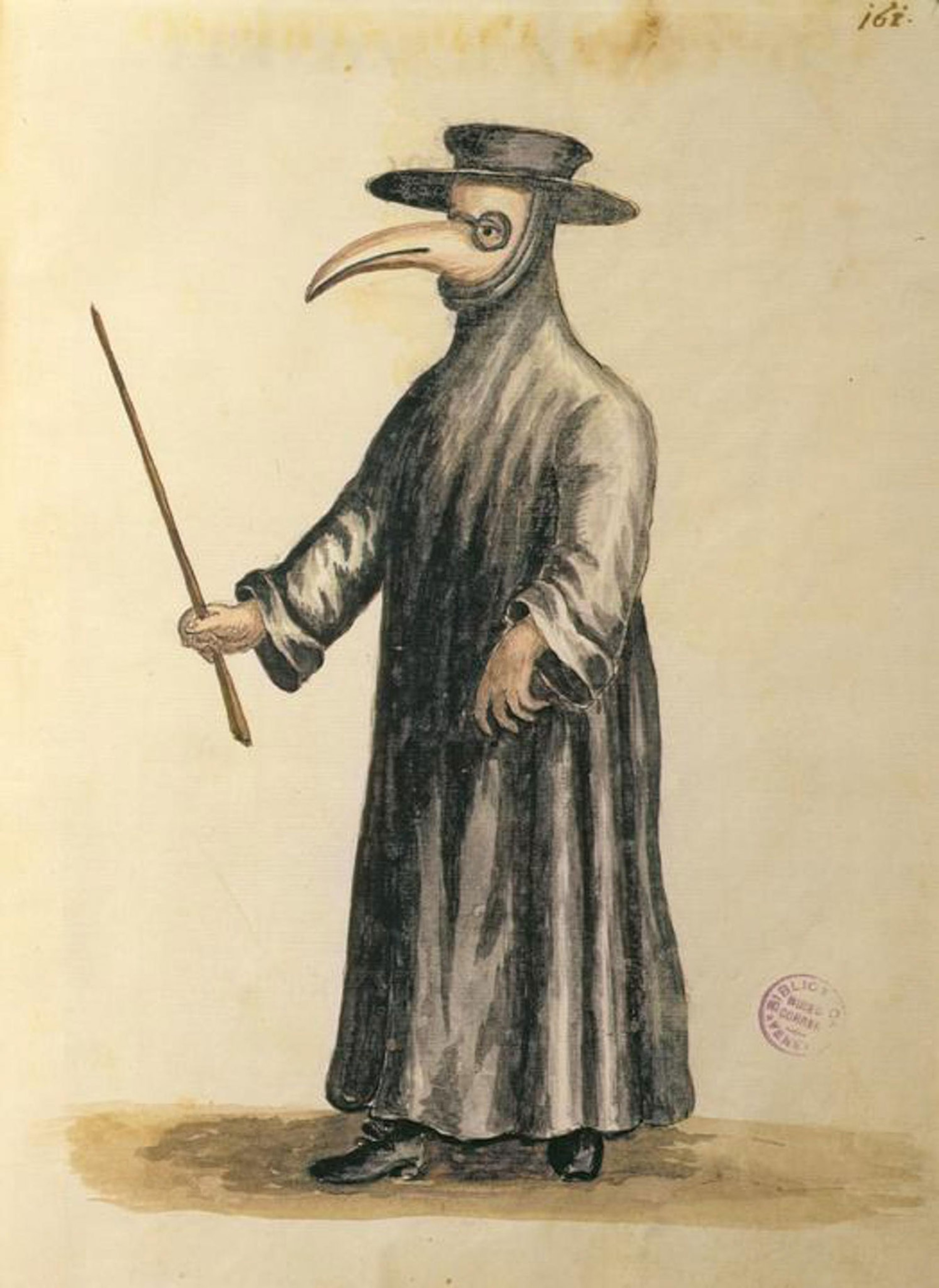

(Why plague doctors wore those strange beaked masks)

Many small mammals act as hosts to the bacteria, including rats, mice, chipmunks, prairie dogs, rabbits, and squirrels. During an enzootic cycle, Y. pestis can circulate at low rates within populations of rodents, mostly undetected because it doesn’t produce an outbreak.

When the bacteria pass to other species, during an epizootic cycle, humans face a greater risk for becoming infected with plague bacteria.

Rats have long been thought to be the main vector of plague outbreaks because of their intimate connection with humans in urban areas. Scientists have more recently discovered that a flea that lives on rats, Xenopsylla cheopis, primarily causes human cases of plague.

When rodents die from the infection, fleas jump to a new host. The inevitable flea bite transmits Y. pestis. Transmission also occurs by handling tissue or blood from a plague-infected animal, or inhalation of infected droplets.

Plague cases today

Plague is still a public health issue today, popping up in various parts of the world. The World Health Organization closely follows cases, most of which have appeared in Africa since the 1990s.

(When bubonic plague first struck America, officials tried to cover it up)

Between 2004 to 2014, the Democratic Republic of the Congo reported the majority of plague cases worldwide, with 4,630 human cases and 349 deaths. Scientists link the disease’s prevalence in the Democratic Republic of Congo to the ecosystem—primarily mountain tropical climate.

The U.S., China, India, Vietnam, and Mongolia are among the other countries that have had confirmed human plague cases in recent years. Within the U.S., on average seven human cases appear each year, emerging primarily in California and the Southwest.

Treatments and prevention

Plague is classified as a Category A pathogen because it readily passes between people and could result in high mortality rates, if untreated.

This classification has helped stoke fears that Y. pestis could be used as a biological weapon if distributed in aerosol form. As a small airborne particle it would cause pneumonic plague, the most lethal and contagious form of the infectious disease.

(A quiet plague outbreak has been killing Yellowstone’s cougars for years)

Of conservation concern, federally endangered black-footed ferrets contract sylvatic plague from nearby prairie dogs. It can decimate prairie dog populations, which are a critical food source for black-footed ferrets. Scientists have started to administer a vaccine to prevent outbreaks in prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets.

Most people today survive with rapid diagnosis and antibiotic treatment. Good sanitation practices and pest control minimize contact with infected fleas and rodents to help prevent plague pandemics, like the Black Death, from happening again.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Plague

Johns Hopkins: Center for Health Security

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Priority Pathogens

Plague as a Biological Weapon

Plague: from natural disease to bioterrorism

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Black-footed ferret

World Health Organization: Plague

Britannica: Black Death