DNA in London Grave May Help Solve Mysteries of the Great Plague

Scientists can use samples from skeletons’ teeth to answer lingering questions about the Black Death.

The strain of bacteria that caused the Great Plague of London in 1665 has been identified for the first time. Scientists recovered DNA of Yersinia pestis—known to have been responsible for the Black Death in the 14th century—from skeletons discovered last year during the construction of the new Crossrail underground rail link beneath London.

The Liverpool Street excavation cut through the remains of the old Bedlam Burial Ground, which was used between 1569 and the early 18th century. In all more than 3,300 skeletons were recovered, including a mass grave of 42 individuals who archaeologists suspected may have been plague victims.

The discovery of Yersinia pestis DNA in the teeth in five of these individuals confirms they did indeed die of the bubonic plague and the discovery will likely shed new light on the Great Plague of 1665, perhaps even solving some mysteries about the swiftness and ferocity with which it spread. This was the last round of bubonic plague outbreaks in Britain, and wiped out 100,000 Londoners, nearly a quarter of the city’s population, in 18 months.

“It does not behave that way today. It’s much slower and spreads less dramatically. Could it be that there was some form of mutation?” says Don Walker, senior osteologist at Museum of London Archaeology, who was involved in the sampling. “Or was it to do with host susceptibility and response? Were humans carrying greater disease loads in those days (e.g., tuberculosis) and had poor nutrition, making them more vulnerable?”

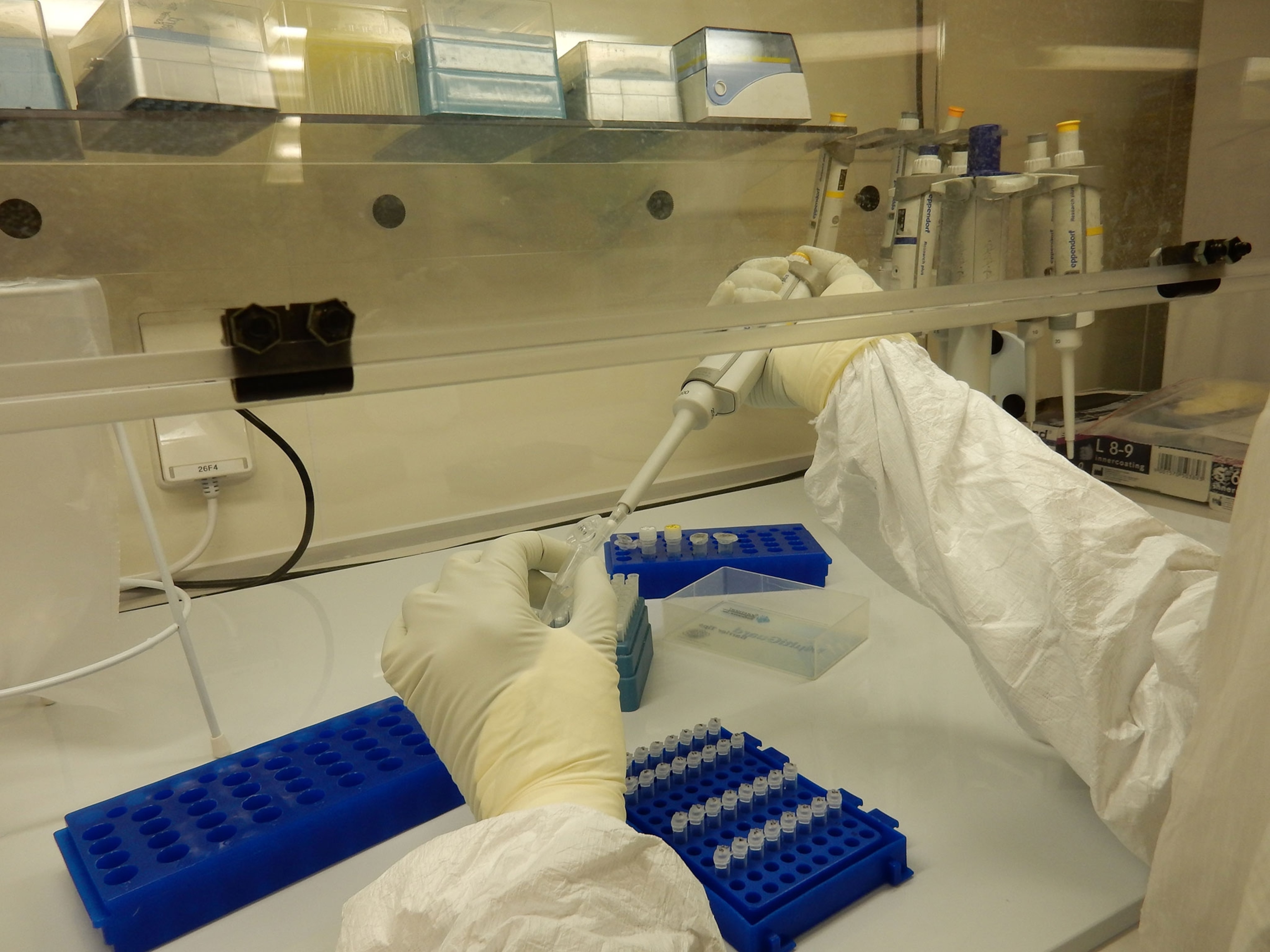

The DNA was identified by teams of scientists from Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and the Max Planck Institute in Germany. They studied the skeletons’ teeth, because enamel acts as a kind of time capsule in preserving the genetic information of any bacteria that was circulating in the individual’s bloodstream at the time of death. The bacteria itself perished shortly after its host did, 351 years ago, so the remains pose no risk today.

Scientists hope to be able to sequence the DNA from the 1665 outbreak and compare it with Yersinia pestis DNA recovered from a 14th century plague pit elsewhere in London.

“We want to know if there was a local/European plague focus—a reservoir of the disease within a rodent population—or were there separate waves of plague coming from Asia,” says MOLA’s Don Walker. “Current evidence suggests the former.”

They also hope to learn more about the five individual victims themselves. So far what is known is that they all were young—one aged between six and 11 years old, the other four young adults under 25. Of those whose sexes can be determined, two were male, one was female.

Stable isotope analysis of strontium and oxygen in the individuals’ teeth will enable scientists to learn if they were native Londoners or if they moved to the city from elsewhere. Carbon and nitrogen isotopes can reveal how much meat, vegetables, and seafood they ate. And microbiome DNA from their teeth can further determine which airborne particles and pollutants they ingested in life.

The discovery comes as London marks the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London, whose cleansing flames have long been popularly credited with stamping out the plague, though the evidence is still open to questioning. “Current thinking is that the plague was starting to slow down by the time of the fire,” Walker says. “The majority of deaths by then were occurring in the suburbs outside the area of the fire, so the fire itself may not have had that much impact.”

One thing is certain, however: After the fire, the plague disappeared and never returned, except as ghostly traces of DNA.

Roff Smith has been a frequent contributor to National Geographic magazine for over 20 years. His most recent story was the February cover, "Under London," on the archaeology beneath the city.