Why Prague is the best place for astronomy buffs

The Czech capital was once a magnet for scientists who studied the stars.

Prague comes by its starry reputation honestly—its history with astronomy and astrology goes back to the 17th century, a time when the two disciplines often blurred together. Under Emperor Rudolf II, a patron of the arts and sciences, Prague became a beacon for astronomers, alchemists, and philosophers.

One of them, Johannes Kepler, was a talented math teacher who was banished in 1600 from Austria for his non-Catholic beliefs. Kepler came to Prague as an apprentice to fellow stargazer Tycho Brahe (the two are immortalized in a bronze sculpture less than a mile from the observatory), and lived in a small apartment at 4 Karlova Street, just off Charles Bridge. As a side gig, Kepler wrote horoscopes for the mystically inclined emperor.

Kepler’s seminal text, Harmonices Mundi, was published exactly 400 years ago. It’s an expansion of Kepler’s studies on planetary motion, in which he proved the planets move in an ellipse—not a circle—around the sun. (If you like to look skyward, here are some of the world’s best stargazing spots.)

As a sound therapist, the text holds a deeper meaning for me: It develops the idea of the “music of the spheres,” or the harmonic theory of planetary motion. (“The Earth sings mi, fa, mi,” Kepler wrote.) It is the basis of my work, where I apply a tool known as a planetary tuning fork to acupuncture points on the body. When I learned that Kepler spent the bulk of his time in Prague refining the theories that went into Harmonices Mundi, I knew I had to go.

Prague is in the center of Europe, and there is an extreme amount of energy here. People who are sensitive, they feel it.

At first, I had a hard time squaring the raucous halls of today’s Prague with its radical beginnings. My guide, Lenka, who leads custom city tours through a company called JayWay, explained: “Prague is in the center of Europe, and there is an extreme amount of energy here. People who are sensitive, they feel it.” In other words, the same force that inspired all those philosophers back then is what lures travelers today, even if they don’t know it.

Take Charles Bridge, Prague’s most visited site: Back in 1357, Charles IV (another metaphysical monarch) commanded the first stone to be laid at precisely 5:31 a.m. on July 9, thus creating the auspicious palindrome 135797531.

Clues to Prague’s cosmic side are scattered throughout the city. Some are hiding in plain sight, such as Old Town Square’s giant astronomical clock, which draws a crowd of photo-snapping tourists every hour when it strikes. Gazing up at its cryptic overlay of rotating disks, medieval numerals, and heavenly symbols, I struggle to read the actual time. But that’s because its function is more astrolabe than clock. The front-facing hands trace the movements of the sun and moon across the zodiac—useful for townspeople who wanted to learn the correct day to receive medical treatment or buy a new house.

On one clear night I head to the eastern dome of the Štefánik Observatory, in the hills above Prague’s Malá Strana neighborhood. Unlike unruly Old Town, things are quiet here. The observatory sits atop the Lobkowicz Gardens, and to reach it, I had taken a funicular. Exiting the station, I had passed through a rosarium, where bushes of pink, white, and red blooms caught the last of the evening light. (Where do the locals go in Prague? Read on.)

Inside the observatory, I find myself staring down the end of a Zamboni-size reflector telescope. Overhead, the entire hemisphere of the roof swivels. I can hear the groan of cogs turning like spokes on a giant bicycle wheel. “Aha! Jupiter!” exclaims the Czech woman who’s in charge, pointing to a bright twinkle fixed between two pine trees in the distance. We look up in excitement, until we realize it’s not fixed after all. “No, it’s an airplane,” she admits. “But Jupiter looks very similar.”

Fifteen minutes later, in the facility’s western and even larger dome, we finally catch Jupiter, rising between the same two trees. Climbing to the top of the ladder, I peer through the lens, and witness, to my shock, the sharpest rendering of the planet I’ve ever seen. It looks like a pastel orange gumball floating in the pure black of space. The image is so crisp that I can even discern two bands of cloud on its smooth surface. Three moons—Callisto, Io, and Europa—punctuate the scene. Looking around me at the four or five other figures gathered in the dark, I am perplexed: How are there not more people up here, seeing this? Then I remember: It’s Saturday night, and pilsner, not planets, is what’s on most visitors’ minds. (Did you know that the world is full of archaeological sites for stargazing?)

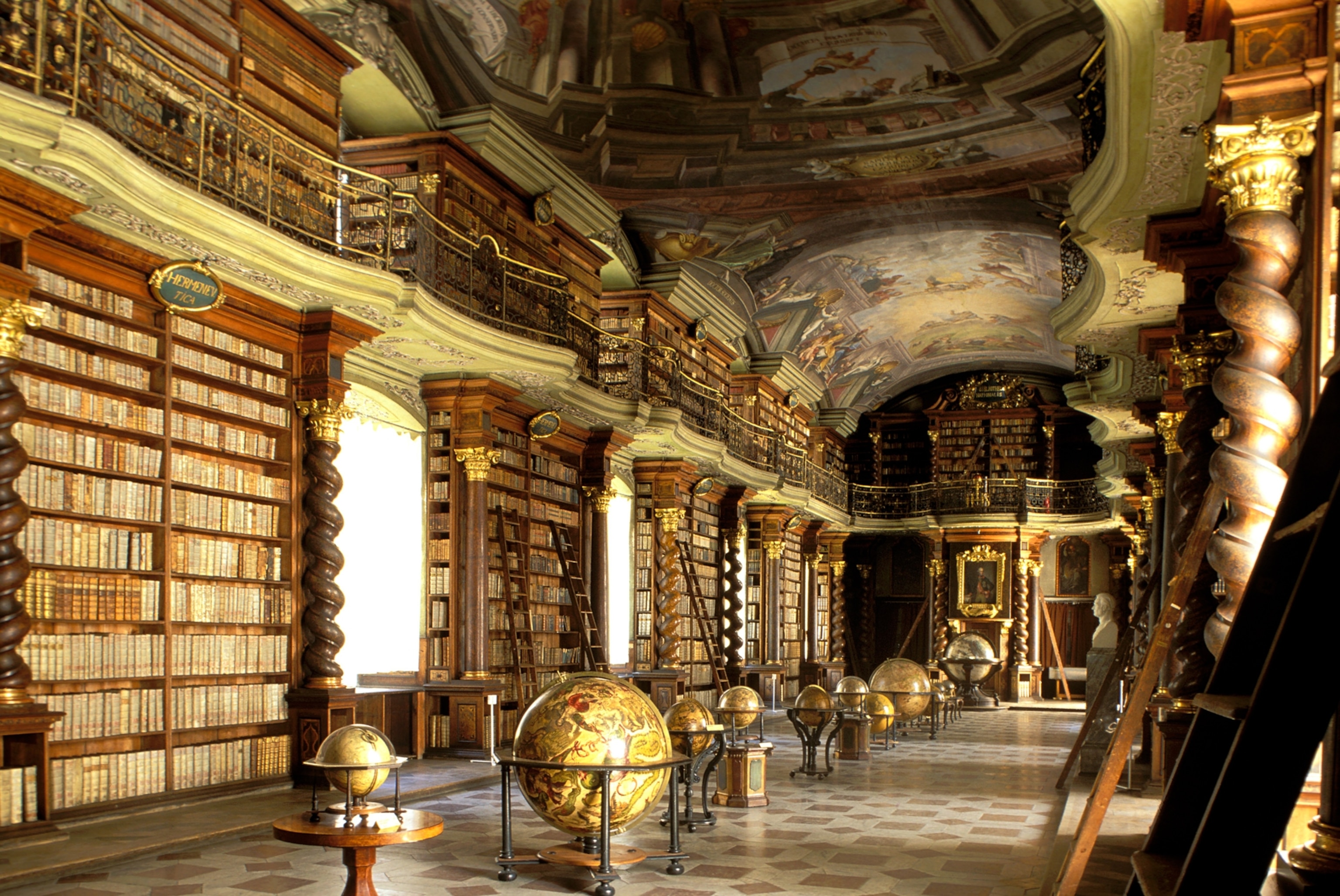

I spend an afternoon at the Astronomical Tower inside the Klementinum, an old, sprawling Jesuit university in the center of the city. Filled with astronomy tools from the 17th and 18th centuries, it is in many ways the last intact monument to starry Prague. Jumping onto the last tour of the day, I join a group of 25 visitors and we ascend single file up a tightly wound metal staircase. The tower’s first floor opens into the National Library of the Czech Republic, with its spiraling wood columns and collection of celestial globes, a hall little changed since 1722. If Dumbledore himself had looked up from perusing a giant tome of spells, I wouldn’t have been surprised. (We love a majestic library. Here are a few of our favorites.)

On the floor above, in the boxlike Meridian Hall—an active meteorological station—we stand where Kepler’s contemporaries once measured the positions of planets with sextants the size of hockey goal posts. Another 50-some nearly vertical steps, and we find ourselves at the top of the tower. On four sides, all of Prague, with its red pointed roofs and saint-bedecked spires, is bathed in golden light.

It is an unforgettable panorama, and one I never would have found had I not let my inner astronomy nerd lead the way. Lesser known than Prague Castle and St. Nicholas Church, this watchtower is a more gratifying visit, as it affords unbroken views of all those other sites, minus the long queues.

Walking back to my hotel, I spot a sign that reads “Kepler Museum.” Excited, I follow a narrow alley down past some buildings but come to a dead end. The museum had since closed, and all that was left in the empty courtyard was a metal sphere, engraved with a Latin quote from Kepler: “Ubi materia ibi geometria.” Where there’s matter, there’s form.

Esoteric Prague is still here, a quiet contrast to the city’s “beer bike” tours. If you hunt for it, a sharper image of choreographed skies and thrilling stellar discoveries comes into view, harking back to a time when humans were just waking up to the mysteries of our solar system.