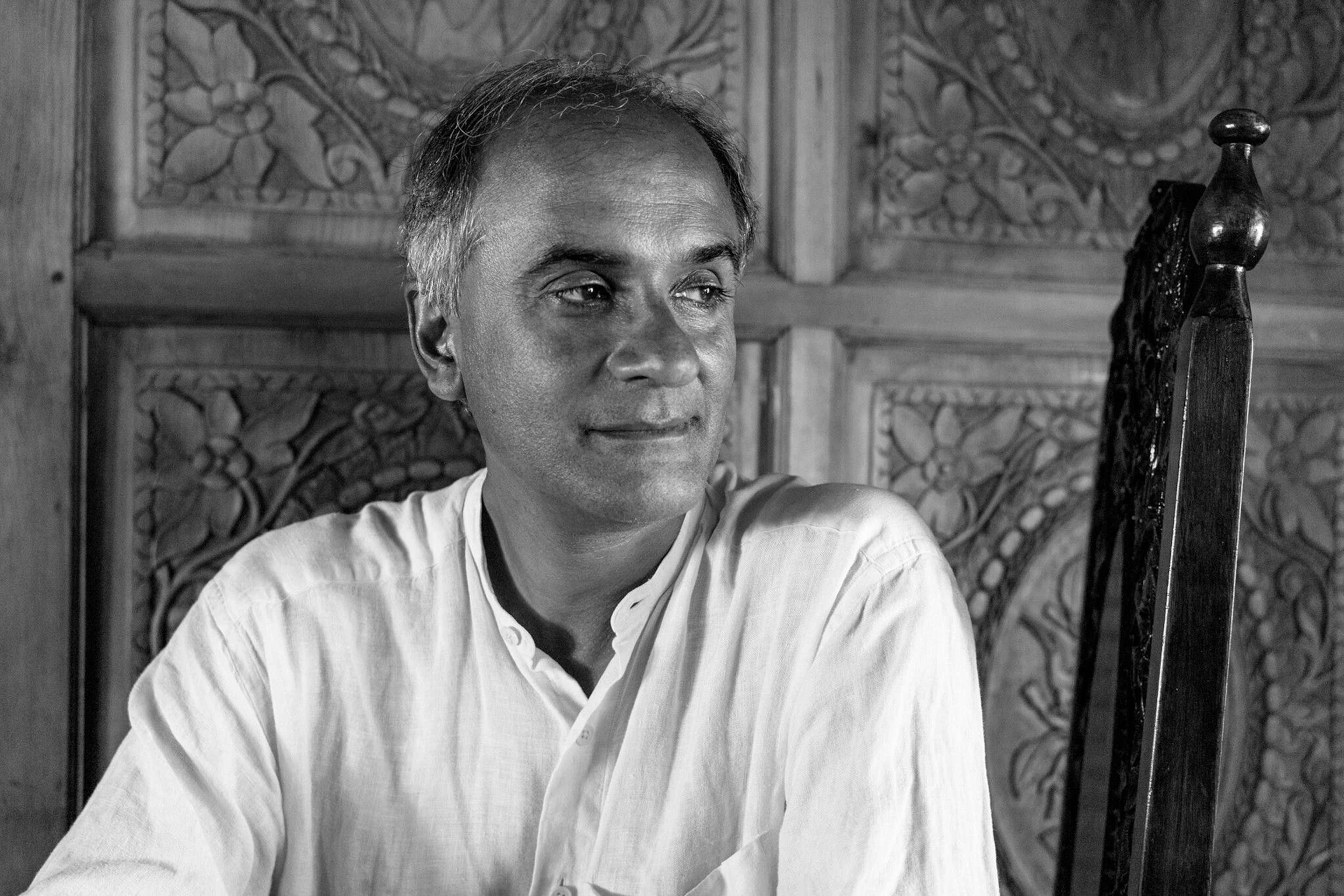

Notes from an author: Pico Iyer on finding the ancient spirits of Koyasan, Japan

After half a century of travel writing, Pico Iyer reflects on the power of Koyasan, the temple-filled town at the spiritual heart of his adopted home, Japan.

Fifty-one stations after leaving jampacked Osaka — the landscape growing ever quieter, the platforms ever emptier — you step out of your train at Gokurakubashi, ‘The Bridge of Heaven’. You get into a clanky cable car and, minutes later, you face a silent country road, with little on it but signs warning of bears. A slow country bus takes you into a settlement consisting of 117 temples, their grey roofs like the prows of ships about to sail off into the mist. You’ve entered the single most powerful spot I’ve discovered in 35 years living in Japan.

Koyasan, or Mount Koya as we might call it, is the centre of the esoteric Buddhist order known as Shingon, a practice so mystical that none of its details, it’s said, were written down, even in Japanese, for a thousand years. It’s the terminus of three separate pilgrimage routes. And everyone who stays there — even you or I — sleeps in an old monastery, eats monastic vegetarian fare (no onions, no garlic) and can observe a fire ceremony every morning as the light comes up. There are no convenience stores or pachinko parlours, no karaoke joints around the sacred slopes. At the end of the thin main road is a graveyard that houses 200,000 departed souls, guarded by tall cedars that have stood there for centuries.

I urge every friend who visits my adopted home to spend two nights on the holy mountain. Walk through the cemetery at night and you can feel the spirits of ancient Japan. Once the light comes up, you can watch robed monks carry breakfast and lunch, every day, to the founder of the community, Kobo Daishi, who stopped breathing in the year 835, but is believed to be sitting still in uninterrupted meditation. Twice I’ve come here with the Dalai Lama, whose practice of Buddhism has its closest Japanese cousin in the mantras and mudras, or hand gestures, of Shingon. Once, on a visit with my Japanese wife, I heard myself screaming — and then she did, too — when we bumped into each other in the night, so full of ghosts does the mountain seem to be.

Most of all, you fall into a different rhythm when you stay here, in cathedral-like quiet, recovering parts of yourself you might never otherwise reach. The majority of the visitors around you are white-clad pilgrims, walking from temple to temple wearing conical hats and shaking bells. On their backs is inscribed a pledge to follow their long-ago leader, Kobo Daishi, to the grave and beyond. For foreigners, the place represents a magnetic trip into the past; not just because you’re returning to a stripped-down, primal, ancestral kind of life here, but also because many of the leading figures of Japanese history are buried in this local equivalent of Westminster Abbey. For devotees, however, this is a journey into the future, a way of reflecting on what awaits at the end of the road.

Days on Koyasan are like days nowhere else. Once, I took a walk with a monk who, only two years earlier, had been an office worker in central Osaka; now, having inherited a temple, he was spending all his days on the magic mountain. I enjoyed lunch every day in a funky cafe run by a young Japanese man and his French wife; they’d travelled the world and decided they wanted to raise their children in a simpler, purer environment, close to the elements. One day in their cafe I met a Swiss monk, Kurt. As soon as he’d come here, he’d felt a piercing sense of recognition; by now he’d spent 27 years living in the Temple of Immeasurable Light, around the corner.

Early each morning, I went to the temple called Eko-in, and watched a ritual bonfire that spoke for a purging of illusions. I hurried back for my traditional breakfast, taken on a tatami mat near the monks. I went to the museum at one end of the community, abundant with Buddhas. And every night I returned for another walk among the stone lanterns and towering trees to the end of the path, known as the ‘Bridge of Ignorance’.

Somehow, during the pandemic, Koyasan began to come back to me more and more often. I started writing a book based on half a century of constant travel, trying to see what all my journeying had amounted to. I thought back to the visions of paradise I’d seen in Iran and North Korea, in Indigenous Australia and across the Himalayas. But I couldn’t get out of my head the ‘Buddhist Paradise’ around the graves of Koyasan. If ever we are to find a better world, I thought, it has to be right here, right now. Not just in the midst of real life, but, most of all, in the face of death. Symbolically at least, the mountain at the centre of Japan might almost be the centre of the world.

Pico Iyer is the author of 15 books. His latest title, The Half Known Life: Finding Paradise in a Divided World, is published by Bloomsbury Circus, £16.99.

Published in the March 2023 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK)

Sign up to our newsletter and follow us on social media:

Facebook | Instagram | Twitter