Is this the most spiritual destination in the Himalayas?

Ladakh is a land of jagged peaks and sprawling desert, where ancient monasteries are draped in prayer flags and Buddhist monks share words of wisdom with travellers passing through.

In the morning light the mountains glow brighter than gold, softer than silk. Row upon row, they weave through the region like gilded threads, embroidering the landscape as far as the eye can see.

I’m standing on a stupa (domed monument) at Ensa Monastery, hanging off its conical crown and staring in stunned silence at my surroundings. Below, a herd of wild horses wanders the valley floor, two foals frolicking carefree beside their mothers. In this stark moonscape of silver rock and dusty plains, with the Himalayas rising in serried ranks beyond, life feels both precarious and immeasurably precious.

Precarious for me, too, it seems, as a worried wave from below summons me down from my perch. Ensa is nearly a thousand years old and while monasteries elsewhere in Ladakh have edged cautiously into the modern age, almost nothing here has changed. It clings to the edge of the mountainside, a haphazard clutch of buildings, home to just five monks and a scruffy mongrel with a flea-bitten tail.

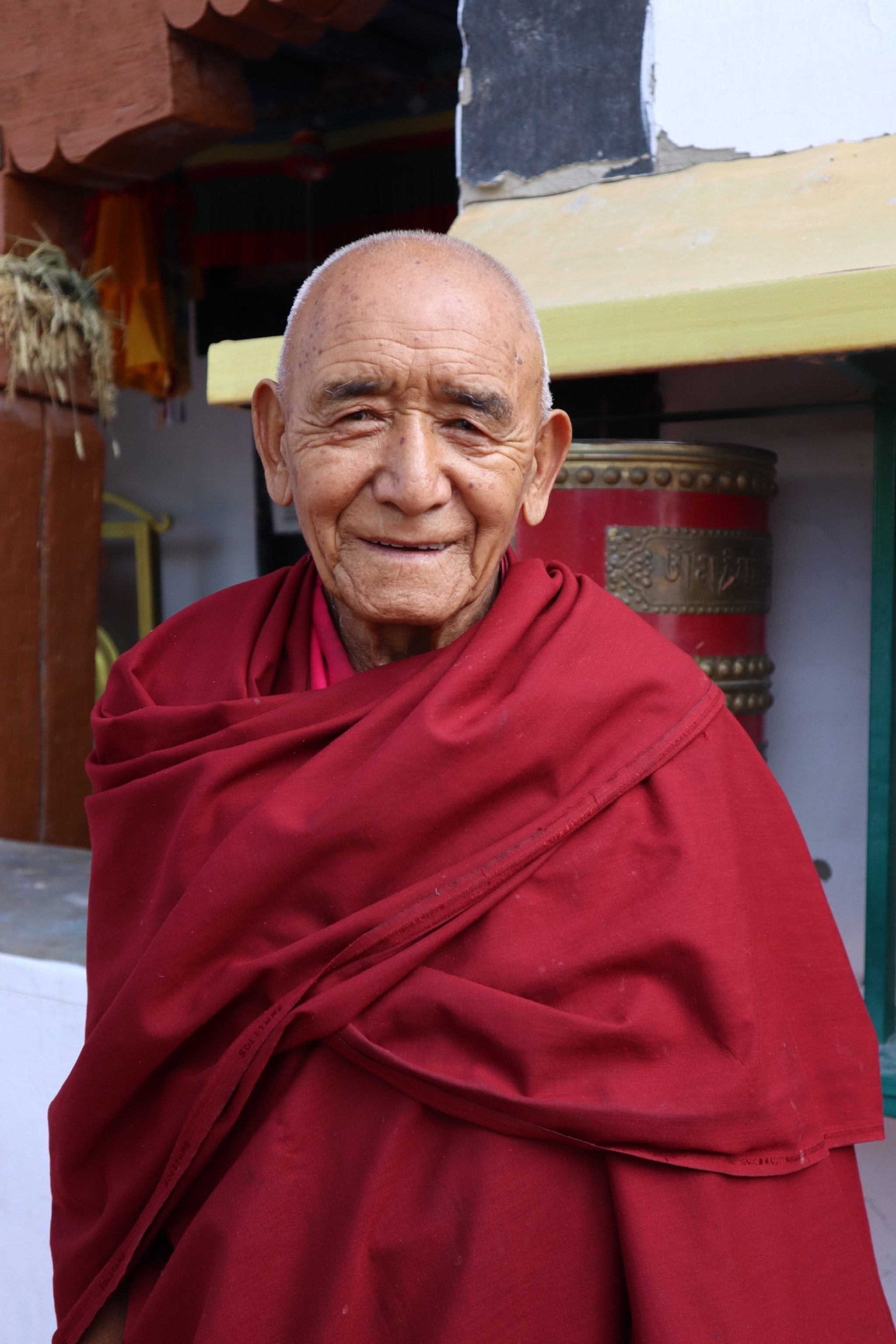

Tenzin, who called me in moments before, now sits serenely in a corner, a scripture so ancient resting on his lap that as he turns its pages, tiny fragments crumble away, joining the dust that hangs halo-like in the air around his head. I kneel at his feet for a lesson in Buddhist philosophy, but he seems more curious about what has drawn me to this far-flung corner of Ladakh.

The Nubra Valley lies in the far north of the region and using the boutique Kyagar Hotel as a base, I’ve spent the past few days monastery-hopping. There are hundreds scattered across Ladakh, from sprawling complexes like Diskit — where I’d sat the day before in a haze of incense among seventy monks chanting their daily sutras — to tiny Ensa, where I kneel now.

“Our postings may last anywhere between six months and a year,” Tenzin explains. “Do I get lonely here at the edge of the world? Perhaps, but it gives your soul room to grow and just look at my surroundings. They’re a constant source of inspiration.”

His words only become more profound the more I see of Ladakh, and the following morning I set off to drive one of the world’s highest mountain roads: the Khardung La Pass. “This region might be considered a desert,” my guide, Paldan, muses, “but just look at the colours. To me, these landscapes seem like something from another planet.”

He points out peaks streaked in shades of purple and blue, while the orange berries of squat sea buckthorn bushes flare like tiny fires burning for the heavens. Fat-bottomed marmots scurry for their burrows as we pass and a shepherd herding a flock of sheep 500-strong cuts a lonely figure on the mountainside.

“This peak is considered a source of good luck,” Paldan explains as we pause beside a boulder draped in thousands of fluttering prayer flags. “Monks make pilgrimages up here in May — the month the Buddha was born — often walking for weeks to reach its summit.”

We drive higher. The air feels thinner up here, the temperature has plummeted and an icy wind buffets the car worryingly close to the cliff edge, but the scenery is nothing short of mesmerising. An endless sea of mountains rolls away in every direction, ridge after ridge dissolving into pale distance beneath a sky of piercing cerulean blue. “You really do feel closer to paradise up here,” Paldan murmurs, almost to himself.

Time takes on a strange quality among the peaks, as though the laws that govern its passing have no power here, but eventually — inevitably — the road crests. At 17,500ft, we've reached the highest point and an altitude on par with Everest Base Camp. Prayer flags whip wildly above us and we linger briefly, breath shallow, before gravity reasserts itself and the descent begins, the landscape slowly folding back in on itself as we drop toward the Indus Valley and Ladakh’s capital beyond.

Shel Cottage may be the world’s most luxurious homestay and that afternoon, I sit down on the rooftop terrace to a late lunch of steaming chicken thukpa (Tibetan noodle soup). Views stretch out towards Matho Monastery and my host, Saumya, explains that two Tibetan monks have been meditating in an isolated trance there for the past year. “Their bodies are said to be possessed by ancient spirits,” he says. “In February, a ceremony will see them emerge to predict the future of the village.”

But it is not Matho that draws me from bed at 5am the following morning. In the half-light, we drive toward Thiksey, its silhouette slowly resolving as though an unseen hand is adding brushstrokes to a canvas. Cascading down a rocky outcrop, the monastery earns its nickname — Mini Potala — its tiered white walls recalling Tibet’s iconic Potala Palace, once home to the Dalai Lama before he fled Chinese occupation in 1959.

We reach the rooftop just as light spills over the mountains. Two monks lift Tibetan horns twice their height and sound them into the cold air, their low, mournful notes carrying across the valley. Overnight, the first snow of the season has fallen, dusting the world white and lending the scene a hushed, ceremonial calm.

Still lost in reverie, I sit among a sea of red-robed monks in the main prayer hall, a steaming cup of butter tea pressed into my hands. “I can see you’ve been touched by this place,” an elderly monk beside me says with a knowing smile. “But nothing is permanent and this moment will pass just as life does. What’s important is how you choose to live it.”

His words resonate: ancient wisdom from a place that feels frozen in time, to take back to a modern world.