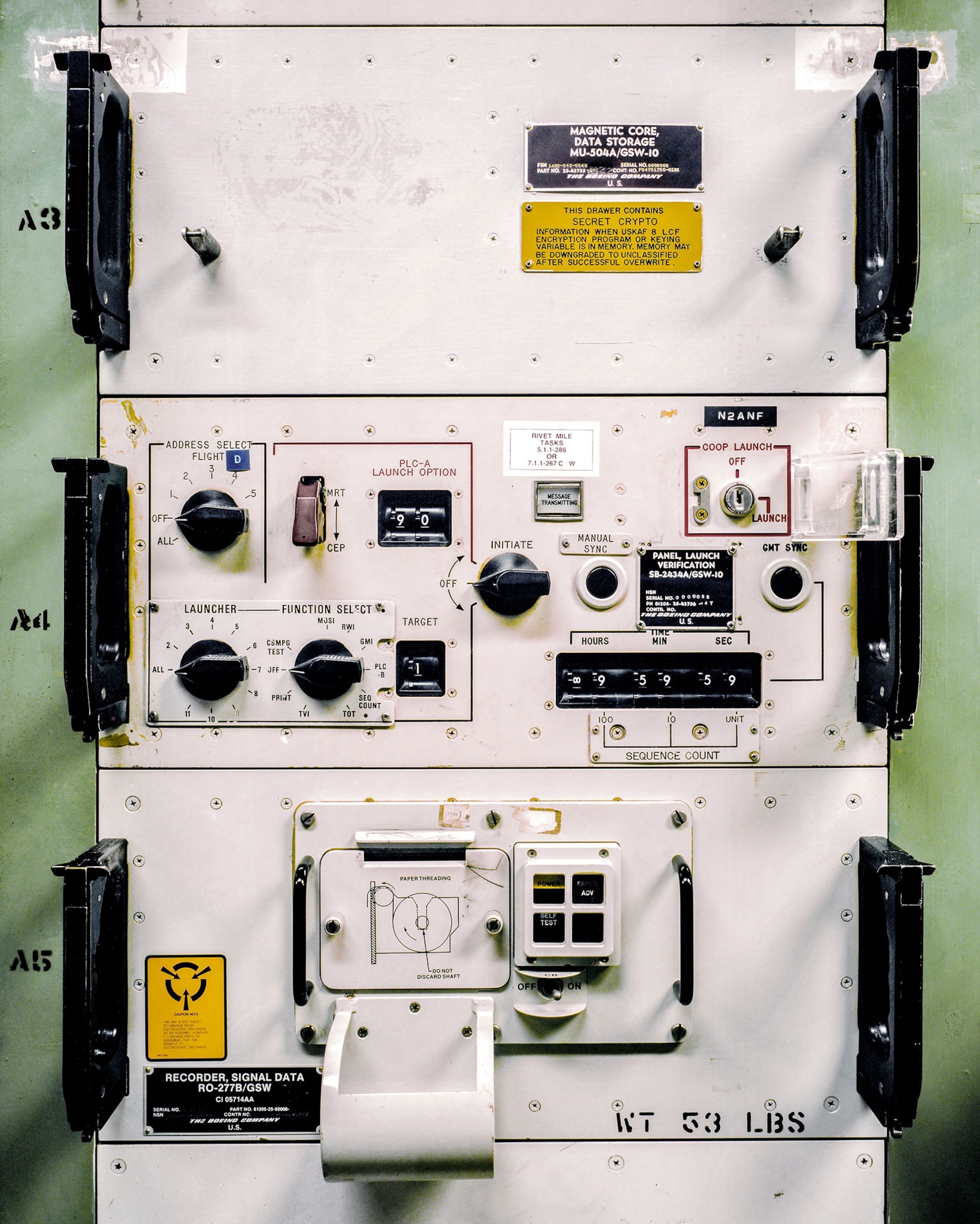

Grey, cushioned, comfortable, the chair doesn’t seem meant for a combat position on the front line of nuclear war. Yvonne Morris sat there on alert in the early eighties. Now, when she leads tours, she steers visitors through simulations of the steps she never had to take: Authenticate the controller's flat, dire command; retrieve the launch codes from the war safe; turn the keys in unison with the deputy crew commander to send a seven-story-tall Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile and its massive nuclear payload hurtling off into the world.

That’s when Morris—a former missile combat crew commander and current director of the Titan Missile Museum—tells the tourist they’ve failed. If the mission to maintain peace through deterrence had been successful, the bomb would never have launched.

In 2018, it’s an effective simulation. But at several points in the last seven decades, most people wouldn’t have needed any help imagining the start of a nuclear war. There were some years where nobody forgot that absolute, omnipresent threat. And though it's gone largely unnoticed for years, current events—and increasing nuclear tourism—are bringing it back into the spotlight.

Old wars

Anxiety and inattention form a repeated pattern when it comes to nukes, suggests Paul Boyer in his book By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age.

In the years immediately following World War II, the United States had an “obsessive post-Hiroshima awareness of the horror of the atomic bomb,” Boyer writes. By 1950, it had faded. But in the mid-fifties, fallout from American and Russian atmospheric bomb tests—miles of ash, dead fishermen, radioactive rain, radioactive milk—renewed public terror. [See photos taken on illegal visits to Chernobyl’s dead zone.]

The national preoccupation with nuclear war nearly disappeared again after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, thanks to a test-ban treaty and the growing impenetrability of nuclear technology and strategy. And though fears of nuclear war resurged during the global proxy conflicts of the eighties, another wave of disinterest followed after the Cold War’s end in 1991: The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) saw the U.S. and the U.S.S.R agree to reduce their deployed nukes, and people were eager to think the threat had passed.

All the while, thousands of warheads remained buried on high alert beneath ranches, homes, and highways.

Underground on the front lines

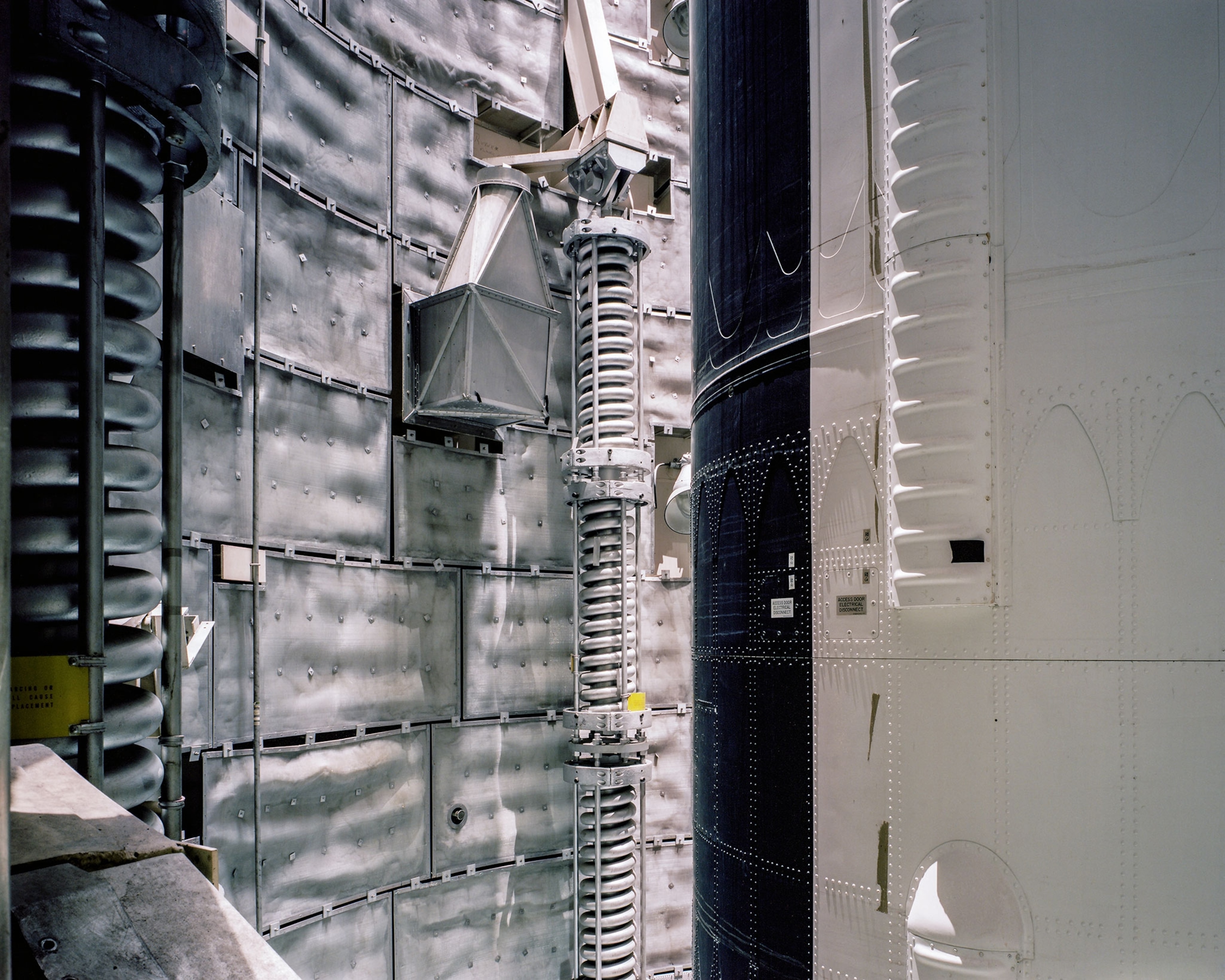

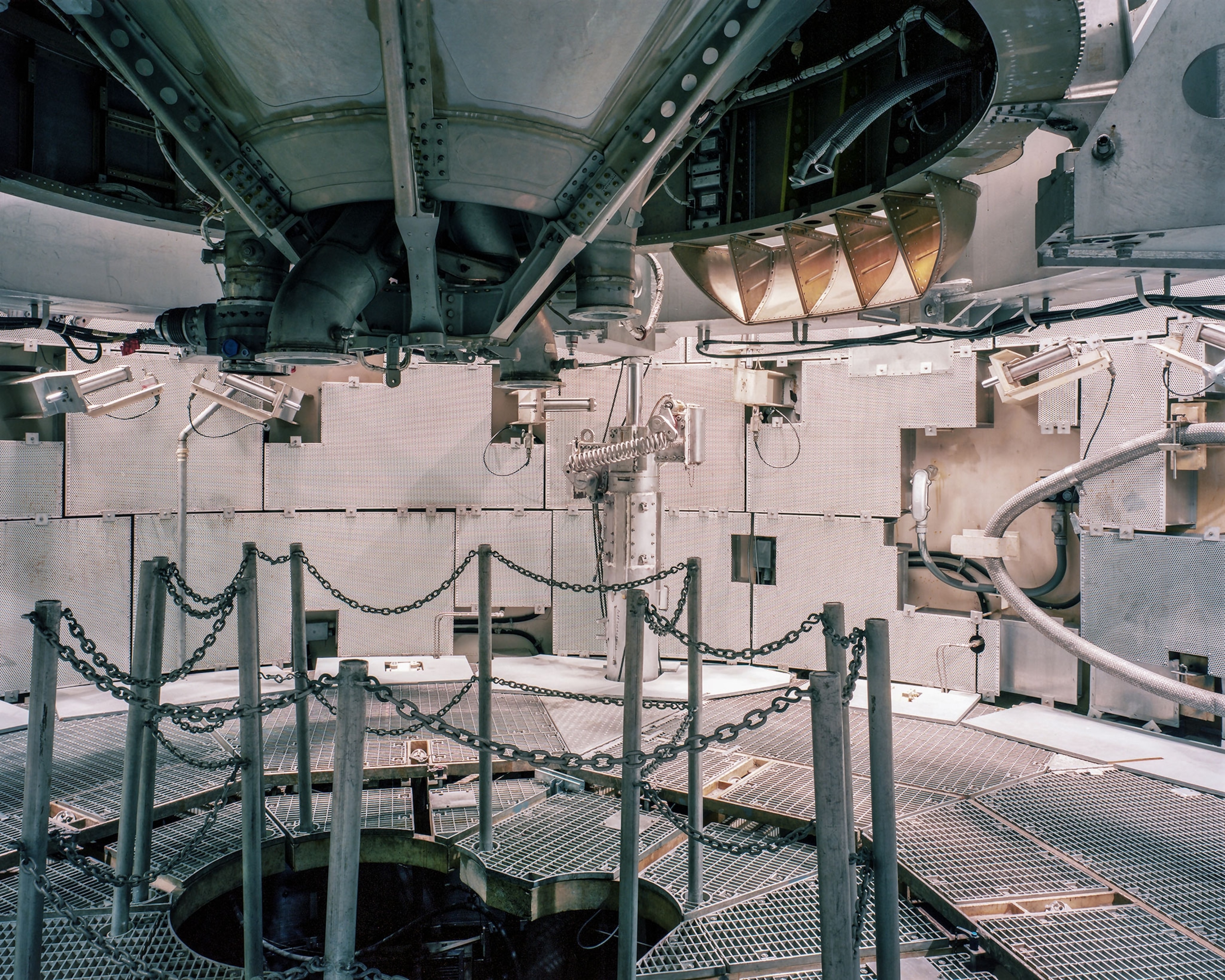

At ground level, the missiles were nearly invisible, their presence marked by antennae, barbed wire fences, and the launch duct door like a small basketball court.

“From a distance, it looks like something unremarkable,” says Eric Leonard, superintendent at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site (MMNHS) in South Dakota. Then you get close enough to read the signs: Use of deadly force authorized. “The distance between mundane and extraordinary is pretty fast.”

In the 1960s, the Air Force planted 1,000 Minuteman missiles across the Great Plains, each with a payload of a little over one megaton. Only 54 Titans were deployed, mostly in the Southwest—but each of these carried a payload of 9 megatons, enough to decimate an area larger than Maui. [Learn how shockwaves from WWII bombing raids rippled the edges of space.]

“What it’s designed to do is erase a city from Earth,” says Leonard. “That’s what it does. But the other perverse part of nuclear weapons is, when you’re building weapons that powerful … the very fact that you have them and they’re ready to go is intended to serve as a deterrent against America’s enemies so that they don’t attack.”

That strategy of mutually assured destruction has been the prevailing rhetoric of the nuclearized world. “[It] enabled us to stand toe to toe, to look each other straight in the eye, and not go to war with each other,” says Morris, who pulled alerts at all 18 Titan silos around Tucson, Arizona, from 1980 to 1984.

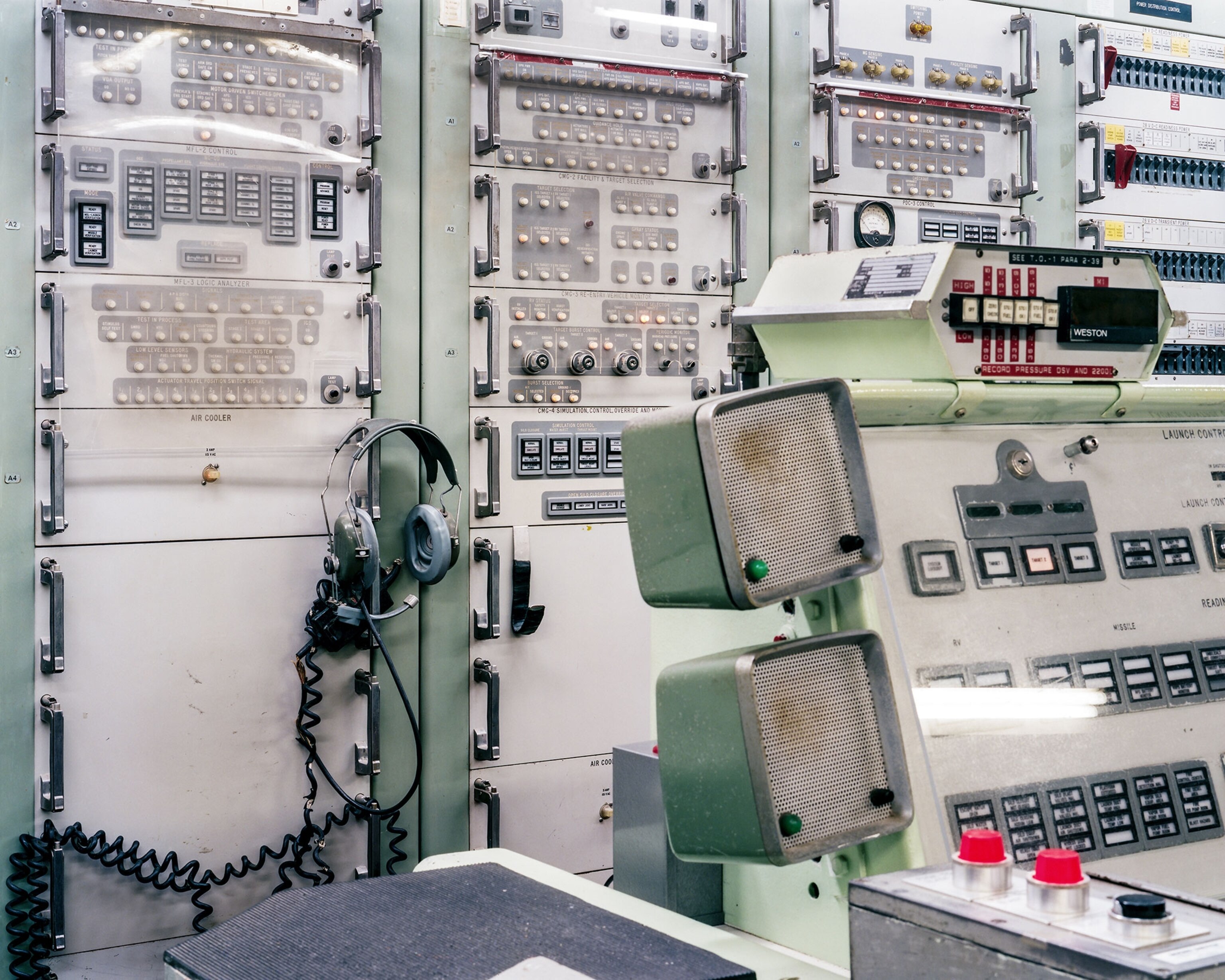

To ensure a missile was always ready to launch within minutes of receiving an order, crews pulled alerts—24-hour shifts that were a dissonant balance of ritualized routine, constant adrenaline, and eerie domesticity.

After a top-secret security briefing on the day’s threats, officers had to prove and re-prove their identity before even getting into the bunker, where they secured the launch codes in the war safe with their own personal padlocks. Crews filled the hours with gruelingly thorough, top-to-bottom inspections of the missile’s every gauge, light, pump, fan, and belt, Morris says.

At both Titan and Minuteman sites, it was absolutely impermissible for a single person to be in the launch room alone. The weapons’ sheer destructive power was too great a risk and too heavy a responsibility to entrust to only one officer; the crew commander and their deputy always acted together. [You and almost everyone you know owe your life to this Russian nuclear officer.]

Yet the presence of immense violence lived alongside the trappings of daily human life. More advanced versions of the weapons that once killed 120,000 people in seconds formed part of the same sites that housed beds, kitchenettes, kitschy morale art, and comfortable chairs.

The accidental doomsday tourist

Today, Leonard and Morris oversee the world’s only two intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) preserved for the benefit of the public.

“The American nuclear arsenal hasn’t grown, but it hasn’t particularly gone anywhere,” says Leonard. “And if national parks are a place for dialogue about what America is and how America works, this is a pretty important subject.”

Recognition of a public need to preserve Cold War missile sites came swiftly: The Titan Missile Museum actually opened before the Cold War ended, and MMNHS is one of the only national historic sites to be listed while less than 50 years old. Visitation to the latter has more than doubled since 2011, and last year, 144,000 park visitors brought about $10 million to the local economy. Though plenty plan ahead—summer tours book months in advance—many visitors are accidental, stopping by on their way from Badlands National Park less than 10 minutes away.

“The most asked question is some variation of ‘Hey, we still have nuclear missiles?’” says Leonard of people’s disbelief. (We do still have a lot: Of the U.S.’s roughly 6,800-missile stockpile, roughly 1,800 are deployed, roughly 400 of those are ICBMs, and almost all of those can fire within five minutes of the president’s order, though nobody agrees on those numbers.)

Not all visitors are nuclear neophytes. Former Cold War missile crews come to show their families the missiles they used to work on, and current missile officers use the retro sites as analogs to the top-secret job they can’t take their families to see today. Both Titan and Minuteman have strong volunteer programs filled with retired Air Force. [See photos of dark tourism sites around the world.]

Interest isn’t limited to America’s Cold War survivors, either: International visitation is growing.

“If you’re not from the United States, your Cold War experience is often much more personal,” Leonard says. “Soviet nuclear weapons wouldn’t take you out in 30 minutes, they’d take you out in four.”

And the barbed nuclear rhetoric between the U.S. and Korea may be renewing both foreign and domestic interest in these unique sites. [Powerful photos show what nuclear "fire and fury" really looks like.]

Documentary photographer Adam Reynolds, who spent two years taking these photos, links that interest to a Cold War nostalgia. “Now, with nuclear proliferation becoming more and more of an issue, we’re looking back almost like, ‘Wow. It was a lot simpler. There were just two sides.’”

Reynolds acknowledges the missile sites’ importance, but also the “strange feeling” they elicit: “What are we actually celebrating? Are we celebrating how strong we are, that we can destroy the world? Or is it sort of a morality lesson or a cautionary tale that we’re trying to preserve?”

For Morris, the goal is a little clearer.

“[We want] people to leave here understanding, at least vaguely, what a nuclear weapon is, what its capability is, how expensive it is to maintain and operate, and what’s required,” she says. “And to help [people] make a decision about what they want the future of nuclear weapons in the United States to be.”

“You can read about nuclear weapons all day long,” she adds, “but it is unlikely to have the same impact on you as standing ten feet away from an intercontinental ballistic missile.”