Exploring the Arctic can be life-changing. Here’s how to do it responsibly.

Follow these tips to help preserve the fragile tundra and the people who call it home.

Cheryl Rosa will never forget the light and the cold that greeted her on her first trip to Arctic Alaska. “It was extremely windy and extremely flat and extremely white,” she says of landing in Utqiaġvik (then called Barrow), which sits at the edge of the Beaufort Sea. Now the deputy director of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, Rosa first visited the region in 2000 to do fieldwork for her thesis.

The landscape grabbed the Massachusetts native whole. “Travel to the Arctic leaves an indelible impression on the visitor. Its sheer immensity and the fragility of its environment are two things that really blow people away,” Rosa says.

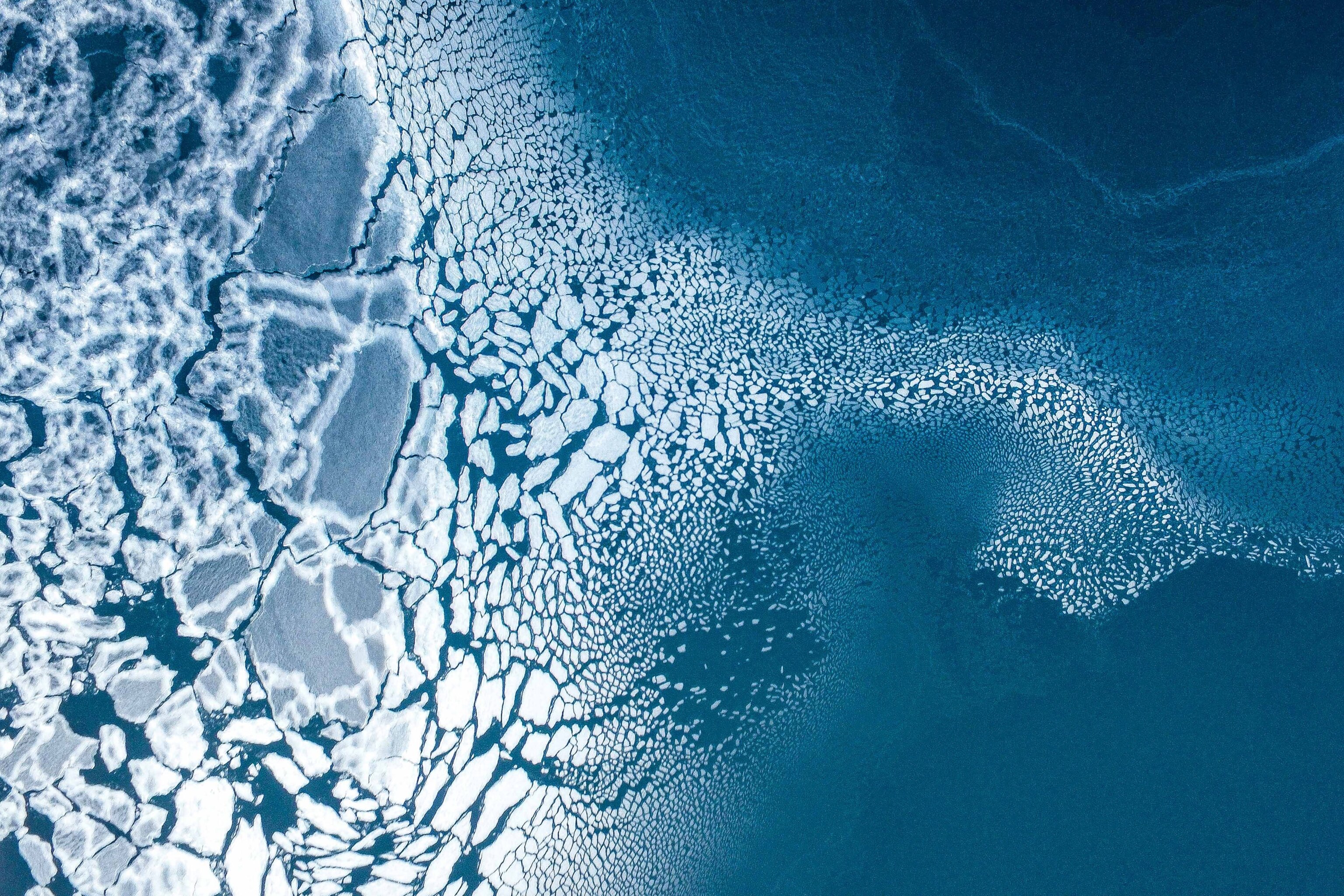

The Arctic is ground zero for climate change, and what happens in the Arctic has an astonishing trickle-down (or perhaps flood-down) effect on the rest of the planet. The region’s surface air temperatures have warmed at two times the rate of the rest of the globe; sea ice is disappearing rapidly; permafrost is melting; and the number of caribou that graze the land has declined by almost half, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Arctic Program. (Here’s what life looks like inside the Arctic.)

Scientists have made it clear that humans are driving climate change—but if we act quickly and globally, we might be able to reverse some of the damage.

The Arctic is not just an idea we read about in the newspaper. It’s land. It’s sea. It has been home to humans for thousands of years. And for those who can make the trip, there’s no better way to connect with the region than to meet some of its people, stand on the vast tundra, or look out on the Arctic Ocean.

I started visiting Alaska from my then home, New York City, 18 years ago. The trips grew longer and longer, and I finally moved to Anchorage in 2013.

The Arctic began to feel less remote, less an idea than a real place. I’d meet Arctic scientists while out at breweries, and at my local yarn store I’d make friends with people who had grown up there. Talk of the region swirled around me. The Arctic stopped being lines on a globe and photos in books, and became a place I wanted to explore, to write about, to protect. It is both part of the state I now call home and a region that connects the U.S. to other nations, a place we all should safeguard together. Ice doesn’t obey borders when it melts into the sea, causing ocean levels to rise.

My first trip to the Arctic—a mid-July day trip with a group up to Coldfoot in the Brooks Range—only fed my growing fascination with the region. How could one ever spend enough time there, an area that crosses eight countries and 5.5 million square miles—about the size of 631 New Jerseys or 34 Californias? How could I return home ever thinking, well, I’ve seen enough, or I’ve met enough local people, or I just can’t look at another walrus? Ridiculous thoughts, all.

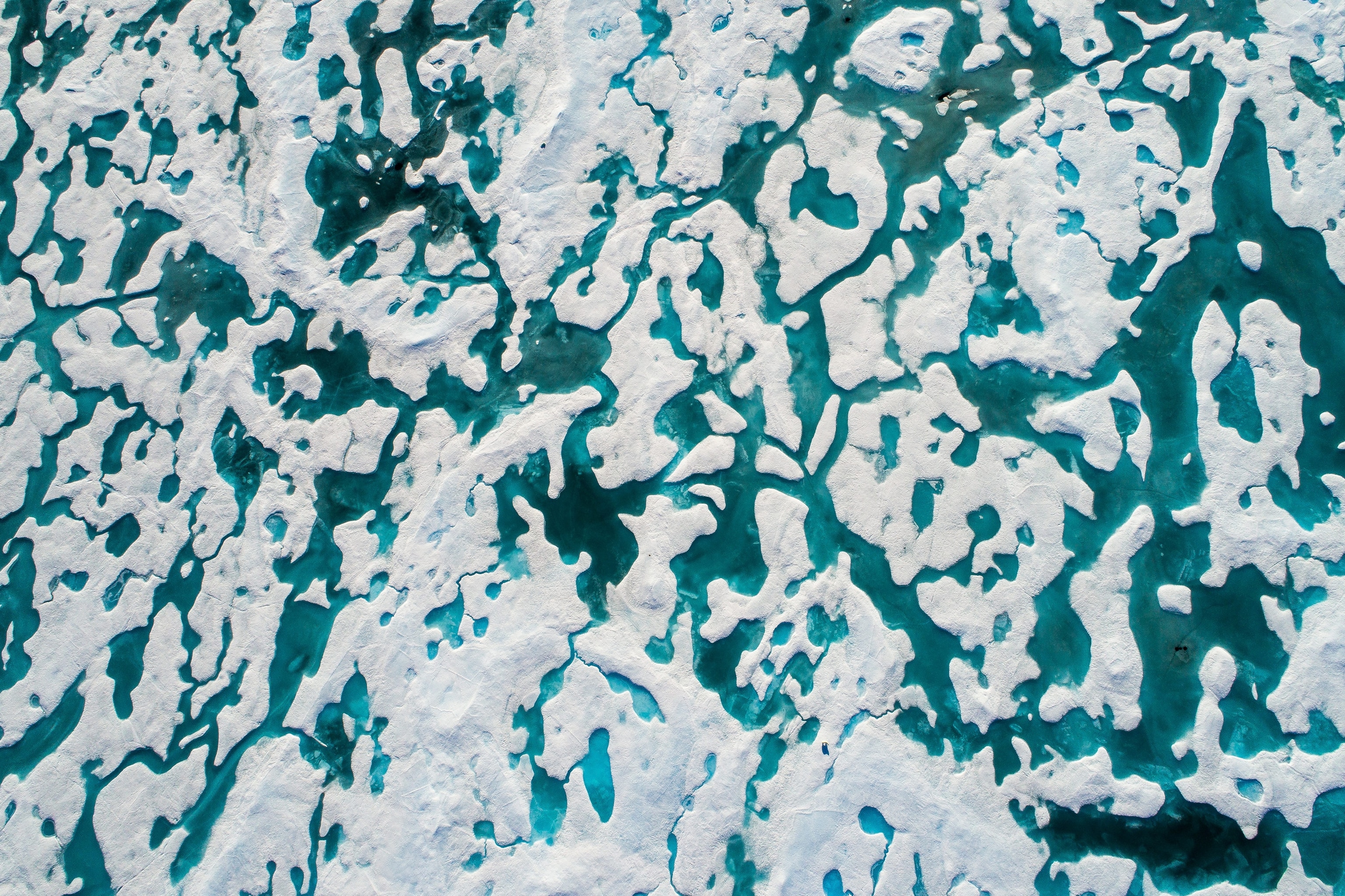

Brooklyn-based artist Zaria Forman, who is the art curator for the new polar ship National Geographic Endurance, is a case study in the ways travel to the Arctic can transform a life. Forman’s mother, a photographer, first took her to Greenland in 2007. Until that trip, Forman “knew of climate change as this distant subject,” she says, but it opened her eyes to issues, including the ways locals had to adapt their lifestyles because of the changes in their environment. Now she travels to Arctic regions for at least a month at a time, photographing and sketching areas that are “intriguing compositionally” and evoke strong emotions, in order to make large-scale pastels “as realistic as possible to give the viewers the same feeling.” (Discover awe-inspiring images of icy adventures in Greenland.)

“There are so many kinds of ice,” she says. “The Arctic is an endless source of inspiration.”

Travel to the Arctic changed John Gaedeke’s life even before it began. I first came across Gaedeke on Instagram, easily the most accessible way to tour the Arctic. Gaedeke is manager of Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge, 225 miles north of Fairbanks and 60 miles above the Arctic Circle, in the Brooks Range. His parents built the lodge in 1974, and it is still his home for half of each year. The nearest neighbors are 50 miles away, in Bettles. Arctic travel grips his guests as soon as they board the plane to get there. “The big transformation is on the two-hour flight in here,” he says. “Within 20 minutes of leaving Fairbanks, they don’t see anything. It’s so remote.” Even the villages that punctuate the landscape disappear from sight within seconds.

The other day, I added a new item to the list of places I want to experience in the Arctic, a list which includes visiting Ellesmere Island in Canada, watching polar bears in Greenland, and talking to the people of Nunavut about what it takes to collect qiviut wool from musk ox. The new place on my list is called Anaktuvuk Pass, in the central Brooks Range. I had called the Simon Paneak Memorial Museum in this Nunamiut Inupiat village to interview Louisa Riley, president of the museum, and Vicky Monahan, the curator. When travelers come through the village, Monahan provides a quick immersion tour into the life and history of her people, of how the U.S. government forced them to give up their nomadic ways. She sees the impact of climate change on the land and on the Inupiat lifestyle. The summers are shorter and the winters warmer, making it harder to harvest the meat, berries, and other plants they depend on for their subsistence.

“I paint a picture where they get an understanding of what we’ve been through and what we’re doing today,” Monahan told me.

“We don’t have much choice,” Riley said. “You adapt. We’re real resilient.”

Here are the ways to be a good steward

—Go with tour groups that are “respectful of Arctic residents and their culture,” says the U.S. Arctic Research Commission’s Cheryl Rosa. “Too many people can overwhelm small villages. Finding tour groups that work with local communities is important.” (Learn six ways to be a better traveler.)

—Take nothing but photos, unless you buy art or other souvenirs from the local people.

—Learn whose land you’re touring, and ask permission before taking photos of people or their homes.

—When you get home, tell your friends and family about your trip and help them understand what issues are in the balance.

Says Rosa: “I do believe most visitors leave with a better understanding of why the Arctic is important—and how high the stakes are.”

- National Geographic Expeditions