Follow Kerala's water from source to sea for a glimpse into southern India's soul

Rivers and lakes form a sacred geography in the South Indian state of Kerala, where travellers can trace waterways that have been shaping myths, legends and religious practices for millennia.

At the foot of Brahmagiri Hill in Kerala’s tea-wreathed highlands, the Papanasini stream rises from a fern-collared hollow. It’s almost clumsy at first, an amber cordial that fumbles over rock and rosewood. Then, dashing towards Thirunelli Temple, it suddenly splits in two, flowing around a bather getting dressed on a jumble of grey-blue rock, the gnarled banks around him peppered with clay urns and piles of fragrant ash.

“It’s said that if you make an offering to your ancestors here, it’s as if you journeyed to the holy city of Varanasi,” says my guide, Pradeep Murthy, removing his glasses to wipe away a layer of condensation as we stand at the edge of one of South India’s most sacred streams. “That’s why people come here — to make sure their relatives’ souls find peace. ‘Papanasini’ literally means ‘destroyer of sin’.”

Water trickles through the spiritual bedrock of India. It’s there in the Upanishads, the ancient Hindu scriptures that first outline the concept of karma. In those sacred texts, written nearly 3,000 years ago, it’s said that our spirits ascend to the heavens, land on the moon and are then either freed from the cycle of rebirth or rained back onto Earth to nourish plants. By my reckoning, that makes Kerala less a state and more a well of souls. It’s a place where abundant monsoon rains feed no fewer than 44 rivers. It’s a land so amphibious — so lush with lagoons, pools and paddies — that in India’s foundational Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, it’s raised from the ocean by an axe-wielding warrior sage called Parashurama, one of the 10 avatars of Vishnu.

Of Kerala’s many rivers, all but three have their source here in the mountains of the Western Ghats. Thirunelli Temple, close to where the Papanasini originates, is my first stop on a new tour with InsideAsia that traces those waterways as they slide towards the Arabian Sea, passing through remote rural communities where water remains a central, sacred element. On their journey west, they breathe life onto everything they touch. Moss-green paddies rise from the clay. Temple pools swell. Assam shrubs release a fragrant mist over the hills. But just as Kerala’s rivers give life, so too do they absorb it, soaking up the stories and souls of the people who live along their banks.

Pradeep’s own story is clear just by looking at his wrists. On the left, he wears a faded silver bangle that gives him the air of a holy man; on the right, a GPS-enabled watch. Half philosopher, half adventurer, the guide’s spent as much time exploring Kerala’s wild places as he has meditating on the divine. “There’s this great quote,” he says, as we amble towards the main temple. “It goes: ‘religion is sitting in church thinking about kayaks; spirituality is sitting in a kayak thinking about god’. I think that captures my philosophy.”

Pradeep explains that it was here, where Thirunelli Temple now stands, that the great god Brahma found his missing brother Vishnu resting beneath an amla tree. It’s said the Papanasini absorbed the divine energies of the surrounding woods, earning it the purifying powers of the Ganges. The flow of pilgrims to the stream is just one example of how water sustains the cultural practices of Kerala — a place where man, nature and spirituality remain fundamentally entangled.

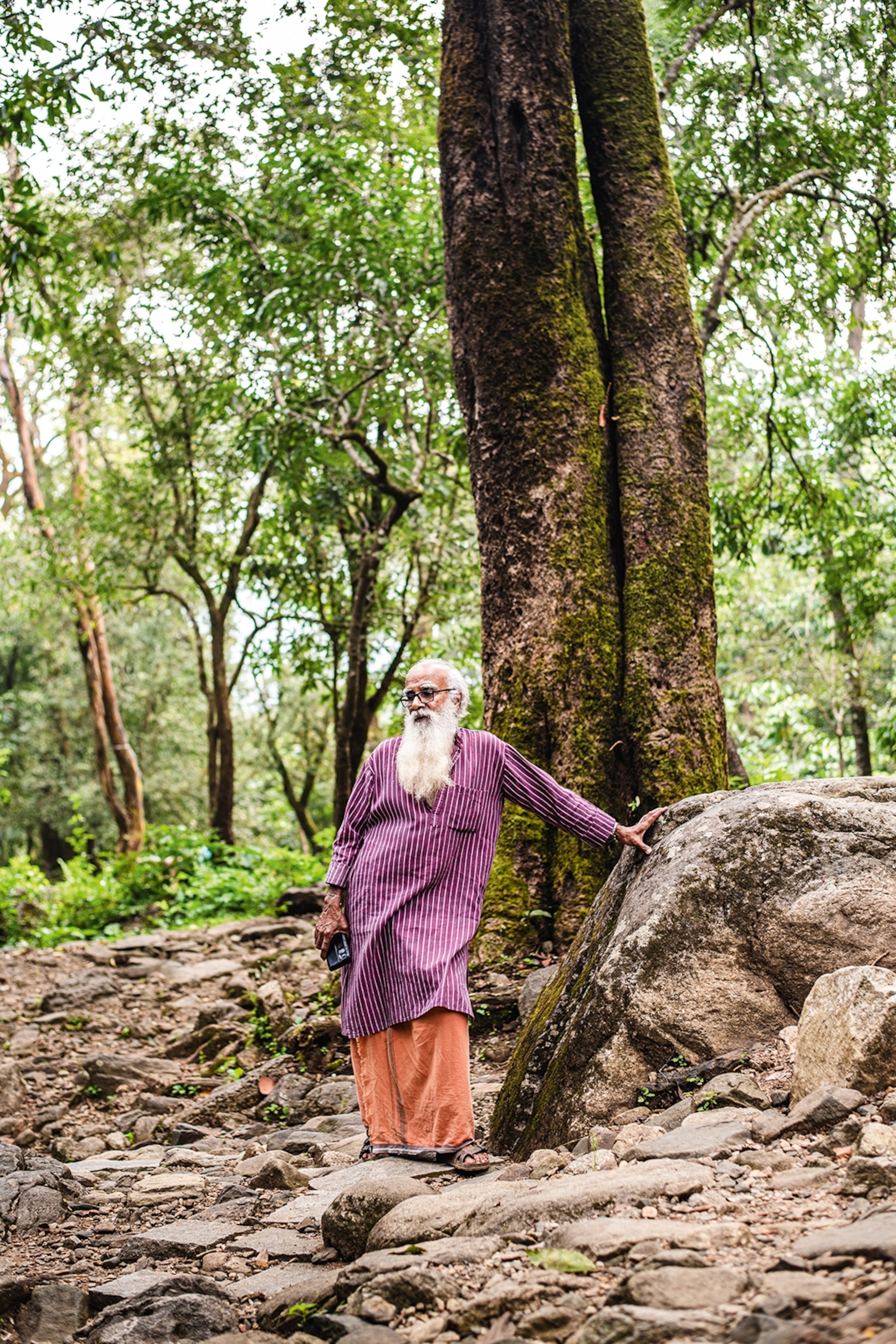

Few people embody that entanglement more than local farmer Sukumaran Unni, who, while joining us on our walk, pauses to gaze over the temple’s lily-gilded pond, his beard a grey mist around the crescent moon of his smile. Sukumaran’s family have worked a small farm in the valley below since 1921, when his grandmother first planted her turmeric on the wild banks of the Kalindi. He’s now in his seventies, and a lifetime spent alongside the water has left him more river than man. His eyes are tea-coloured pools. His stride is slow and meandering. And as he points out the stone symbols of Vishnu standing in the temple pond — the conch, the wheel, the mace and the lotus — wisdom flows from him in a long, unbroken murmur. “Rivers run through us all,” he says, rolling up his shirt sleeves to show me the blue tributaries running along his forearms. “Our hair is forest, our bone is rock and our blood is water.”

Searching for Sita

The next morning, Pradeep and I bundle into a people carrier to chase the Papanasini south. It’s soon swallowed up by the Kabini River, whose arteries splinter the land into a jigsaw of rice paddies, banana groves and densely wooded islets. We reach the Kuruva Island delta, where we find Ravi Kasuvan wandering through his rice fields — his wash of jet-black hair just visible above a sea of green. Born and raised in the hilltop hamlet of Cheriyamala, he’s set to be our guide on a short hike through woodland and paddies towards his home. “We do these walks for two reasons,” Pradeep explains. “To give people a view of this riverine ecosystem, but also to show how it’s shaped the way of life here.”

Ravi is a member of the Kuruma tribal group, an Indigenous people who have lived in the forests surrounding these paddies for thousands of years. Once fierce hunters, many served as bowmen in the armies of Keralan prince Pazhassi Raja during his war against the British in the late 18th century. Today, they farm the fertile lands around the Kabini, whose waters nourish their crops of gandhakasala — a fragrant rice variety that sweetens the morning air with the scent of sandalwood. “When I was younger, this river was our only source of water,” Ravi explains, guiding us along a bank thick with mahogany and cinnamon. “The government eventually built wells, but when there was a drought a few years ago, they all dried up. Again, the river saved us. The Kabini gives us life, agriculture, everything.”

It also features in the Kuruma’s origin story. In local versions of the Ramayana, an ancient epic recounting Lord Rama’s quest to rescue his wife Sita from the clutches of a rival king, it’s to these very woods that Sita is exiled. Here, she’s cared for by the sage Valmiki, as well as a group of forest-dwelling hunters. “The local tribal communities strongly believe that they’re featured in the Ramayana,” Pradeep tells me. “And that it was on their lands that Sita’s tears formed the Kannarampuzha, which is a nearby tributary of the Kabini.”

I’m beginning to understand that, for the Kuruma, the Kabini carries not only life but memory, its waters serving as a repository for folk tales that root people like Ravi to the land. Emerging into a clearing that overlooks a cascade of blue-green water, we stumble across a grand stone table decorated with a trio of five-headed cobras. They’re naga serpent spirits and we’re in a sarpa kavu — one of the sacred Keralan ‘snake groves’ where communities like Ravi’s still perform key seasonal rituals. “Every year, when the rice harvest comes, we’ll thresh three kilos right there in the fields,” he tells me. “Then, we bathe in the waters here and toss that grain to the fish. It’s a way of giving thanks.”

Clambering over the crest of a pea-green hill, we arrive at Cheriyamala, its guardians a pair of dewy-eyed cows that bow at Ravi’s touch. All is quiet but for the call of a coppersmith barbet, which chimes like a hammer on an anvil somewhere in the distance. The air is thick as tea, with anyone not in the fields cooling themselves in one of the portly huts set around the village shrine. Ravi dips inside his family home and returns with an album of sepia-toned wedding photos. Leafing through its pages, he pauses over a shot of himself and his wife walking along the Kabini, their forms ghostly below an arch of branches. On the next page, we see the whole village marching down to the same river in white robes, then marching back all smiles and wet eyes. It soon occurs to me there isn’t a single photo in which the Kabini isn’t somewhere in the background. It’s always there, sliding seaward, the oldest member of the wedding party.

A meeting with the gods

The following day, driving towards the coast, we stop by Thonikadavu village for lunch at Greenhills homestay: a jewel box of forest ghost flowers and swallowtail butterflies perched high above the Payaswini river. Owner Rathnakaran Nair, thin as a mango trunk, hands us cups of blue tea infused with lemongrass and butterfly pea flowers, then guides us onto a wooden deck, where his wife Soumya is flipping chapatis over a stone oven. Sitting above a valley of swooning palms, we eat the flatbreads hot off the griddle, dipping crispy fragments into the array of curries, curds and chutneys being laid out on banana leaves before us. “Sadya,” Rathnakaran explains. “A festival dish here in Kerala.”

Every flavour I come across — wild basil, turmeric, allspice — Rathnakaran later points out growing tall and fine in his garden. It’s remarkably lush. Across northern Kerala, a combination of pollution, deforestation and climate change has critically lowered water tables in recent decades, but Rathnakaran’s lands are as verdant as they were 50 years ago. By way of explanation, he guides me into a suranga: a sarcophagus-shaped tunnel used to collect the underground water percolating through the laterite hills around us. I feel my way through its labyrinth of narrow chambers to the source of Rathnakaran’s Eden: a porous eyelet of rock dripping beads of pure, silver water. It’s hard not to think of Sita here, her tears enough to fill an entire river, and begin to understand why gods and water so often intermingle in Keralan folklore. “Water is life here, so it’s only natural that people start ascribing it a mythical power,” Pradeep says. “If a river dries up, you know you’re not long for this world. Maybe gods are a way of communicating some of those fears.”

That afternoon, we find ourselves overlooking the final destination of the surunga’s mineral-infused waters: Erikkulam, a small village perched at the confluence of streams in the coastal Kasaragod district. Arriving on its outskirts, we wander towards a great bowl of clay-rich rice paddy. Nearby, a father and son are spinning cooking pots beside a great earthen kiln, brows furrowed in concentration. “The people here have been harvesting this clay for pottery since neolithic times,” Pradeep tells me. “Every year, on 16 April, they’ll light lamps and head out to pull it from the fields. They’ll then replant the paddy, leave it to fallow and wait for the rivers to inject their nutrients. It’s all one big cycle.”

Pottery isn’t the only tradition to run deep in this village. We’ve come to witness a theyyam, a trance ritual during which the village deity is said to possess a human called a theyyakkolam, using them as a vessel to relay messages from the gods. Ceremonies take place throughout the North Malabar region at this time of year, often in the dead of night, with rural communities like this one gathering to welcome their incarnate deity. I’m glad the sun’s still shining, because the people of Erikkulam are about to summon one of the oldest and most intimidating spirits: Vettakkorumakan, a mischievous hunter who, in the Mahabharata epic, is sent by Vishnu to protect the people of Kerala.

The man set to introduce us to this spirit is local teacher Ratheeshkumar Kizhake Veetil, who we find outside Erikkulam’s main temple dressed in a milk-white mundu robe. Walking through plumes of incense, he leads us to Vettakkorumakan’s shrine: a blood-red sanctum set below the branches of an elengi tree. “Look inside,” he says. I peer into the shrine, half expecting to see Vettakkorumakan, bejewelled and clutching his hunting bow, staring back at me. But he’s not home. “In most parts of India, the deity’s spirit is said to be concentrated in an idol,” Ratheeshkumar explains. “But here we say the gods are fluid, always moving through the universe. They can enter the soil, the animals — even humans.”

Swept up by the river of villagers flowing down to the temple green, I soon find myself face to face with the theyyakkolam — his skin painted ruby, his mudi crown a teetering pile of silver. In front of him, the elders wait to welcome Vettakkorumakan, gifts of rice, spices and burning oil set about their feet. “The theyyakkolam is always a member of the lowest caste,” Ratheeshkumar tells me as we settle into our seats. “But on this day, they become a god.”

The musicians strike up, using thammattama drums to hammer out a hypnotic beat that erases all capacity for thought. Then come the attendants, who quickly set about painting a pair of pond-green eyes onto the theyyakkolam’s heavy lids. As the pace quickens, he begins to jitter all over, occasionally raising his peacock plumage to fly across the stage. Vettakkorumakan is nearing now, and the village elders know it. They stand to welcome their protector, each tossing a single kernel of rice at the performer’s feet. Spices are burnt and a small wooden mirror is placed in the theyyakkolam’s painted fist. “Watch, watch,” says Ratheeshkumar. “The spirit enters the moment they see their reflection.” The theyyakkolam opens his eyes, but it’s not a man who stares back, it’s Vettakkorumakan — and he’s wild with fury.

For the first time the painted god speaks, though not in any language Pradeep or I can understand. “He’s speaking to the elders in riddles, telling them what problems need overcoming in the village,” Ratheeshkumar tells me. “It’s the language of gods, so it’s not going to make total sense to us.” It flows from the theyyakkolam in a torrent, admonishments giving way to yelps and clamorous battle cries. It’s a language that bickers with itself, a tongue that rises and falls like a wave. It is, I realise, the language of water.

Watching the water

On my final morning in Kerala, we hit the Malabar backwaters: a great labyrinth of lagoons and lakes running along the jungled fringes of the Arabian Sea. The steamy air is aromatic with woodsmoke and marsh mud as I head out on a bike ride with self-taught birdwatcher Amal Satheesh, who points out bone-white egrets and needle-tailed bee-eaters along the way. At one point, we burst through the palms and emerge onto a stretch of sand below the walls of Bekal Fort, where we find a group of moustachioed fishermen plucking glinting fish from their nets. Muthodhi Ayathar, the local temple priest, watches over the morning’s work, squares of gold hanging from his earlobes. “A single tub of fish usually fetches around 4,000 rupees [£33],” he explains, the sea breathing in and out behind him. “Today they’ve caught only sardines, but they can always sense a good catch. All they need to do is watch the water.”

That evening, legs weary, I board the Lotus Houseboat — a traditional kettuvallam whose wooden interior is filled with ornate rugs and paintings of yakshini river spirits. It’s an apt place to end my journey, having once been used to ferry rice and spices from the highlands to the coast. Above its teak helm rests a carving of Ganesh, the elephant-headed remover of obstacles. Yet, gliding along the Valiyaparamba backwater, there’s little standing between me and the ocean, bar a skinny strip of bent palms.

As the sun starts to tinge the water pink, I take a cup of sweet masala chai onto the boat’s upper deck. At the stroke of 6pm, the mosques along the shore begin the call to prayer, the voices of muezzin singers mingling with the sound of the bansuri flute streaming from a nearby Hindu temple. For a fleeting moment, they seem to be serenading the ocean itself, and suddenly I’m back on the banks of the Papanasini, overlooking that lily-covered pond with Sukumaran. “The name Vishnu basically means all encompassing,” he’d murmured. “And what’s the one thing that’s all encompassing? Nature.” He’d grinned then, a smile so wide it seemed to fill the whole valley. “Perhaps, whenever we worship the gods, we’re really worshipping nature.”

How to do it

Getting there & around

Virgin Atlantic and British Airways run daily direct flights between London and Bengaluru. Carriers such as IndiGo run short domestic flights from Bengaluru to cities in northern Kerala like Kannur.

Average flight time: 9h50m

Kerala’s state buses are a cheap, fast way of moving between towns and villages. The region also has a good train network, connecting major railway stations like Thiruvananthapuram, Ernakulam and Kozhikode.

When to go

The dry season between December and February is a popular time to visit, with temperatures generally ranging between 30C and 35C. Far quieter is the period immediately after the Northeast Monsoon, around November, when the land is lush and elephant sightings are common. Kerala is best avoided during the monsoon season, which peaks between June and August and often brings torrential rain and widespread flooding.

Where to stay

Parisons Resort and Plantation, Wayanad.

Neeleshwar Hermitage, Kasaragod.

What to read

The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy. £9.99

The Ramayana of Valmiki: The Complete English Translation, Robert P Goldman and Sally J Sutherland Goldman. £25

Is a River Alive?, Robert MacFarlane. £25

This story was created with the support of InsideAsia.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).