What is ‘Gothic’? It’s more complicated than you think.

Hidden in the architecture of some of the world’s most famous buildings is a cultural exchange between Europe and the Middle East.

When fire devastated the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris in April 2019, the architectural historian Diana Darke noted in a Twitter post that of course everyone knew the famous twin tower and rose window of France’s finest Gothic cathedral were copied from a Syrian church in Qalb Loze built in the fifth century. The post went viral: amplified or rebutted, triumphed or tossed.

Darke was surprised at the reaction to what historians have established as a well-known path of influence: the East-West trade in architectural ideas. It was argued centuries ago that key defining elements of the Gothic style were borrowed from the Islamic architecture of the Middle East. The soaring pinnacles of the Palace of Westminster in London, the pointed arches of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, and the rose windows of Notre Dame all point to the influence of Islamic design.

(Three years after a devastating fire, Notre Dame rises again.)

But from early in the 19th century, these contributions were forgotten, and Gothic became celebrated as an intrinsically Northern European style. In Britain, it was only in the revival of this medieval style of architecture that it started to be called “Gothic.” The Revivalists no longer dismissed the Gothic as a crude or barbarous form, and instead repurposed it as a national, patriotic style.

By knowing this deeper history of some of Europe’s most iconic buildings, travelers can approach these well-known attractions with new eyes and can appreciate that the “East-West divide” isn’t as deep as we are often led to think.

Reviving the Gothic in England

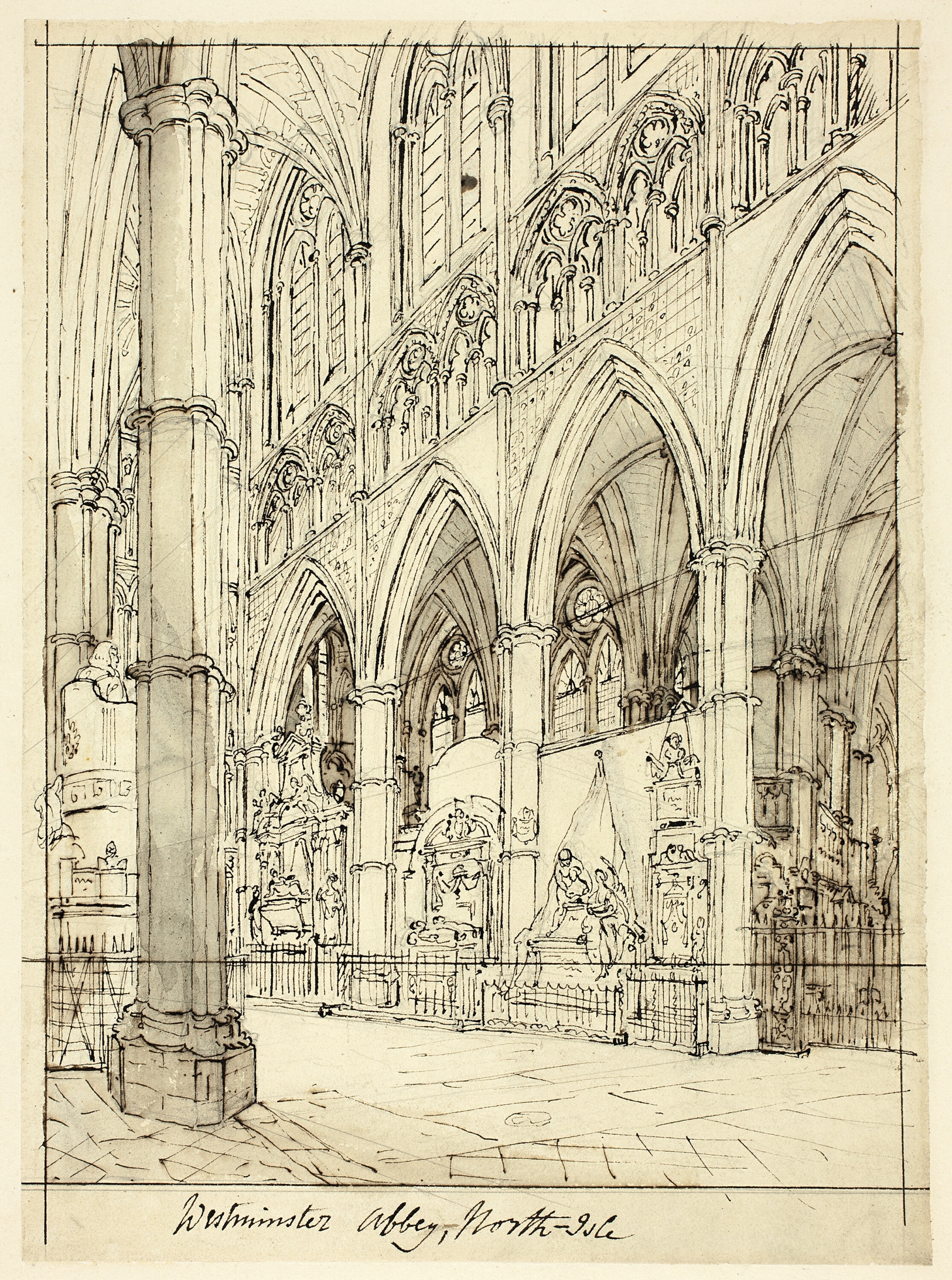

Rekindling elements from the greatest medieval cathedrals in Europe, such as London’s Westminster Abbey and Paris’s Notre Dame, Gothic Revival architecture defined the imperial might of Victorian England.

(These are some of Europe’s most extraordinary cathedrals.)

You can see its grand scale scattered throughout London, from the 1872 Albert Memorial in Hyde Park, built to remember the Queen’s beloved consort, to the ostentatious layering of arches on the sweeping 1873 facade of the St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel London (formerly Midland Grand Hotel) at St. Pancras train station.

The chief advocate of this Gothic Revival in England, Augustus Pugin, claimed that it was a properly Christian architecture that swept away a heathenish devotion to Greek or Roman symmetries. The influential tastemaker John Ruskin argued in 1851 that it was the expression of a northern European sensibility, a mark of virile and restless tribes like the Goths. Gothic Revival style was supposed to symbolize order, tradition, and continuity in a volatile modern world.

Nineteenth-century architect John Carter considered the word Gothic “a barbarous appellation” and argued that it should simply be called “English.” In the midst of a long war with revolutionary France, Carter declared the Gothic “our National Architecture,” rooted in centuries of tradition. After fire destroyed the Palace of Westminster in 1834, it was inevitably rebuilt in the Gothic style.

Yet elsewhere, even at the height of the Victorian Gothic Revival, it was clear to many that the Gothic had traveled from the East.

Islamic influence on the Gothic

When architect Christopher Wren officially won the commission in 1673 to rebuild London’s most iconic building, St. Paul’s Cathedral, after the medieval Gothic church was destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire, he chose to design it in neo-classical style. The west front entrance portico was made of 12 Greek columns below and eight above, framed by symmetrical towers. It is rational and ordered, a mathematical wonder. Wren explicitly dismissed the irrational, asymmetrical “Gothick,” which he argued would be better called “Saracenic.”

“Saracen” was the term used in medieval Europe to group together Arab Muslims. Wren supposed that it was during the Crusades (from 1096 to 1291) that Western Europeans fighting against the expansion of Islamic states in the Middle East first glimpsed the pointed arches, ribbed roofs, domes, rose windows, and minaret towers that were typical of religious buildings and palace complexes across large swaths of the Islamic East. Once the crusaders returned home, what Wren called the “sharp-heeled arch” began to appear over new church doorways, and minarets became models for cathedral bell towers and spires.

(This historian uses lasers to unlock the mysteries of Gothic cathedrals.)

Even as Wren dismissed the device of the pointed arch as it appeared in the Gothic for lacking “proportion, use, or beauty,” he still relied on the East for the most striking element of St. Paul’s—its majestic dome. Ancient mosques all over the Middle East use domes to crown their sacred spaces (such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, completed in 691).

Gothic Revivalists worked hard to invert Wren’s argument. They said it was Greek or Roman neo-classicism that was the suspicious foreign import. However, Wren was historically correct.

Islamic influence surfaced in other design elements as well. The interior of London’s Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition in 1851 in celebration of the British Empire’s global reach, was actually painted in bold colors that the designer Owen Jones had taken from the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. He considered the Islamic palace the finest form of architectural expression in the world. Jones’s choices were initially controversial, but his celebration of Moorish styles and polychromatic buildings of the East meant these became fully incorporated into English architecture.

(Read why this ancient city of sultans is a 21st-century wonder.)

Soon enough, the impact reached out from sacred and public spaces into the worlds of commerce. The English department store, so central to the luxurious Victorian shopping experience, was also borrowed from the covered markets and bazaars of the Middle East.

The continuing interplay of East and West

Creative dialogue between East and West continues into the present day. The 2021 short list for the Stirling Prize, one of the most prestigious architectural awards in the United Kingdom, included the beautiful Central Mosque in Cambridge, designed by Marks Barfield Architects.

The wooden roof beams over the main prayer hall spread up and out like intricate tree branches. It is an echo, perhaps, of the lovely theory proposed by Bishop William Warburton in 1760 that the ribbed ceilings of Gothic churches derived from “northern people having been accustomed, during the gloom of paganism, to worship the deity in groves.” This was purely speculation, as roof ribbing came from Eastern building solutions.

This modern mosque design, like the Gothic Revival church, points to the underlying truth that many architectural forms are products of an intricate interchange of different cultures. These patterns of mutual influence produce ingenious fusions and hybrids. Ideologues would place the East and West in implacable opposition. But so many of the spaces we traverse every day reveal a very different, and much more optimistic, history.