The two-hour climb to reach the summit of Mt. Takachiho-no-mine, on Japan’s southwestern island of Kyushu, is a hard slog. But for determined hikers the reward from 5,164 feet (1,574 meters) up is worth the effort: a spectacular view of the surrounding peaks and the often-smoldering Sakurajima volcano on the far side of Kinkowan Bay. There’s also a monument on the mountaintop – an oversized, bronze three-pronged spear jutting from a rock pile.

The spear, known as Amanosakahoko, is an odd object to find in the middle of Kirishima-Kinkowan National Park, a 90,500-acre (36,605-hectare) expanse of volcanoes, tidal flats, forests, sand “baths” and crater lakes straddling Kagoshima and Miyazaki prefectures. Odd, that is, until you’ve heard the old folktales about Takachiho-no-mine.

The mountain is the setting for one of Japan’s most widely known myths about a deity’s arrival from the heavenly world. In the story, the sun god sends her grandson – the deity Ninigi-no-Mikoto – to rule the islands of Japan. As he descends to Earth, he plunges his spear through the clouds and into the top of Mt. Takachiho-no-mine. Ninigi-no-Mikoto’s descendants would end up becoming royalty: the deity’s great-grandson, Jimmu, was said to be Japan’s first emperor.

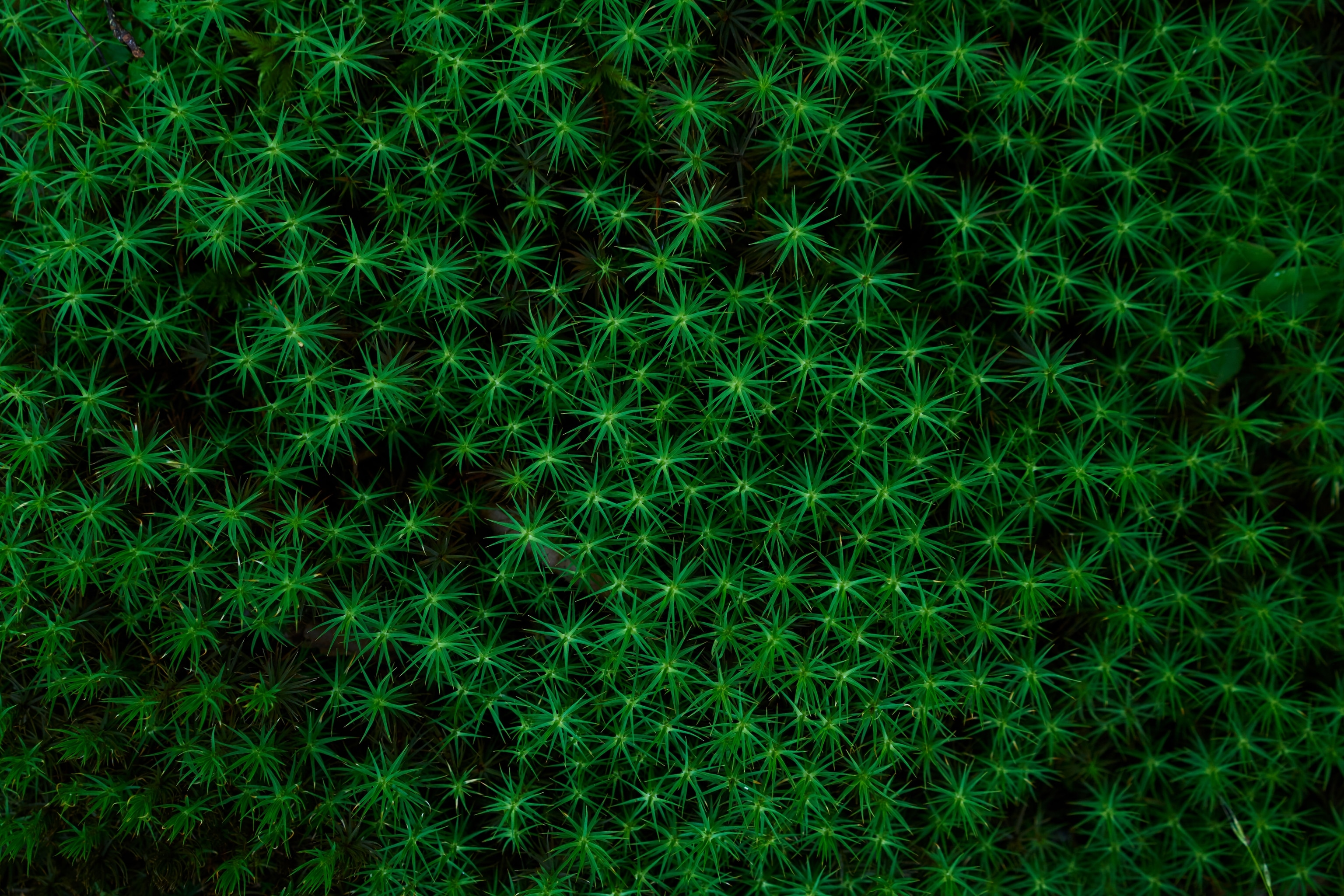

It’s one of the many supernatural tales of spirits and deities that unfold on the peaks and in the forests, marshes and lakes of Japan’s 34 national parks. These chronicles belong to a tradition of seeing otherworldly connections in seemingly ordinary natural objects. “The belief that kami (deities) inhabit mountains, trees and rocks probably came from a sense of fear and awe that people here felt about their surroundings,” said Kikuko Hirafuji, a professor at Kokugakuin University in Tokyo. “For instance, people thought of erupting volcanoes as deities. You can find parallels in Greek mythology, with Hephaestus, and in the Roman god, Vulcan.”

Yet much about Japan’s myths – when and how they were created – remains a mystery, said Hirafuji. That’s true of Ninigi-no-Mikoto’s story, which is contained in the country’s oldest surviving written records, the 8th century Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, but continues to confound modern scholars.

Kirishima-Kinkowan National Park was one of the country’s first national parks to be designated in 1934. At times, its landscape has a dreamy quality: when cloaked in fog and mist, the mountains resemble the isles of a seascape – hence the name Kirishima, which means “fog island”.

This mystical side, combined with the harsh terrain, has made the region a popular pilgrimage site for mountain ascetics (yamabushi). For centuries, they have wandered the slopes and peaks seeking spiritual enlightenment through their interactions with the deities of the natural world. That tradition lives on at Kirishima-Higashi Jingu, a Shinto shrine (established in the 10th century) on the eastern slope of Mt. Takachiho-no-mine. Every month, Masahiro Kuroki, the shrine’s 56-year-old head priest, climbs to the spear at the summit along a steep, rocky trail that rises 3,300 feet (1,006 meters) in altitude. “We worship the mountain itself as a deity, a Buddha. Being on the mountain for our physical and spiritual training is the objective,” said Kuroki, whose shrine is the spear’s owner.

At other national parks, folktales are inseparable from the landscape. In Nikko National Park – a sprawling area in Fukushima, Tochigi, and Gunma prefectures that’s a two-hour train ride north from Tokyo – Mt. Nantai has long been a source of fascination and local lore. Located in Tochigi prefecture on the western side of the park’s 284,000 acres (114,908 hectares), the conical peak is the backdrop for an ancient and epic turf war.

Legend has it that 20,000 years ago the deities of Mt. Nantai and Mt. Akagi (in Gunma prefecture) grappled over ownership of Lake Chuzenji. After a standoff, Mt. Nantai, as a serpent, defeated Mt. Akagi, a centipede; Mt. Nantai’s grandson, Sarumaru, a master archer, delivered the killing blow by shooting an arrow into the giant myriapod’s eye. The fight gave the high-altitude marshland (a habitat for more than 100 species of swamp plants and a vital breeding ground for stonechats, snipes and other birds) near the lake its name – Senjogahara, which means battlefield. There’s also a festival: every January, at Futarasan-Jinja Chugushi Shrine, a Shinto shrine at the mountain’s base, traditional kyudo archers reenact the finale by shooting arrows toward Lake Chuzenji.

Nikko’s UNESCO World Heritage-registered shrines and temples attract the biggest crowds. But the area’s mountains also have exerted a strong pull on people since Shodo Shonin, a Buddhist monk, became the first to scale Mt. Nantai in the 8th century. “Many people don’t realize that Nikko is a great place for outdoor recreation,” said Takamichi Morita, a guide and official at the Nikko Natural Science Museum, located inside the national park. “There are around 100 active guides in the Nikko area who are experts in leading rafting, birdwatching, trail running, snowshoeing, trekking and ice climbing tours.”

The highlight of Mt. Nantai’s May-to-October climbing season falls on August 1. That’s when hundreds of people with headlamps and backpacks gather in the darkness at Futarasan Jinja Chuguji Shrine, a Shinto shrine. At midnight, two Shinto priests dressed in long, stiff robes and peaked caps open the doors of a traditional wooden gate at the mountain’s trailhead. The ceremonial start to the night-climbing season dates back more than a millennium and sets off a three-and-a-half-hour race to reach the top, 8,156 feet (2,486 meters) up, in time for sunrise.

It’s a reminder that Japan’s national parklands are treasured for more than their picturesque landscapes and protections for native flora and fauna. They’re the backdrop for ancient myths, the sacred dwelling for traditional beliefs and a popular fresh-air escape for outdoor enthusiasts to Japan’s wilder side.