The Aso caldera, in southwestern Japan, is a volcanic depression of gargantuan proportions. Nearly 16 miles (25 km) at its widest point, the caldera – one of the world’s biggest – is so large that around 45,000 people live inside of its sloped walls, with space leftover for rice paddy fields and vegetable farms, two train lines and an active volcano. Driving between the north and south rims takes more than an hour.

These are the superlatives that lured veteran National Geographic photographer Michael Yamashita to Aso-Kuju National Park, on the main southwestern island of Kyushu, in the early 1990s. A New Jersey native, Yamashita, 72, has spent more than four decades shooting in hard-to-get-to and sometimes less-than-hospitable settings: China, Japan, Iran, Cambodia, the Korean DMZ, India, Burma, Afghanistan. He’s followed the footsteps of ancient adventurers, from Marco Polo to Japanese poet Matsuo Basho. In his line of work, Yamashita has had to combine physical toughness, an artist’s sensibility and a dash of derring-do. “Photography is about a rectangle. What you keep in the picture and what you leave out are equally important,” he says, during a video call from his home in New York.

Yamashita had personal reasons for going to the Aso caldera. He was exploring his own ancestral roots in Kyushu, the westernmost of Japan’s four main islands, for a National Geographic story. Over four months, he estimates that he shot more than 800 rolls of film – roughly 28,800 images – delving into the culture and terrain of an island slightly bigger than the state of Maryland. “I’m looking for what makes Kyushu special,” he says.

With a knowledgeable local guide, Yamashita drove around Aso-Kuju National Park on scouting trips, imagining the landscape at various times of the day. “In a place like this, you want to know, where are the best views, from what mountain? How do I show this landscape in its best light?”

Aso-Kuju National Park was one of Japan’s first national parks, designated in 1934. Today there are 34 national parks along the archipelago that collectively attract more than 371 million visitors a year. Every park is a unique representation of the islands’ terrain – marshlands, moss-blanketed forests, towering peaks, craggy coastlines and coral reef – spanning from subarctic Hokkaido prefecture to subtropical Okinawa prefecture.

Aso-Kuju’s giant caldera is thought to have been created by four large volcanic eruptions, occurring between 90,000 and 270,000 years ago. For thousands of years, people have lived inside of the caldera and worshipped the five volcanic peaks – Mt. Taka-dake, Mt. Naka-dake, Mt. Neko-dake, Mt. Eboshi-dake, Mt. and Kijima-dake, collectively called Mt. Aso. Local residents are also intimately aware of the awe-inspiring forces of nature that they live alongside: an active volcano, Mt. Aso’s last major eruption was in 2016.

For Yamashita, the park was Kyushu’s landscape at its most dramatic. He was up before dawn and out until dark, shooting images that were nothing like Japan’s dense, neon-lit cities and whiz-bang technologies: fields of susuki pampas grass, their fuzzy tops bathed in morning light; forests, shrouded in fog, fading into the distance; tourists on horseback that appear as colorful dots on a grassy mountainside; bubbling sulphur ponds and steaming hot springs. “National Geographic is about geography, so we try to show the land,” he says. “I’m trying to show something normal in a spectacular way. My job is to arrest the reader, so that in flipping through this story they go, ‘Wow! That’s great!’ and want to stare at it.”

You can’t ask for a more spectacular subject than Mt. Aso, one of the world’s largest active volcanoes. To see it from above, Yamashita hired a helicopter. As the late afternoon sun dipped, he peered down through the helicopter’s open door at smoke billowing from one of the craters. “I’m working the light – in this case, it’s sunset. We are doing a 360 around the volcano and I’m shooting constantly with 3 cameras and different lenses. As I finish one roll, my fixer is reloading the film and I’m shooting with another camera and a different lens. At the same time, I’m telling the pilot to fly where I can get the best picture possible,” he says. “The smoke from the volcano being white, it defines the picture. I’m looking to fill the frame with this beautiful light and gradations of white, thanks to this very intense sun.”

Aso-Kuju isn’t the only national park Yamashita has photographed. For a story about the origins of Japanese gardens, he flew to Ise-Shima National Park, in Mie prefecture, in 1989. Within the park’s 148,000 acres (72,678 hectares) are evergreen forests, mountains, striated and limestone coastlines and inlets dotted with islands and pearl farms and fishing fleets that haul in prized catches of Ise-ebi shrimp, (Japanese spiny lobster) and pufferfish.

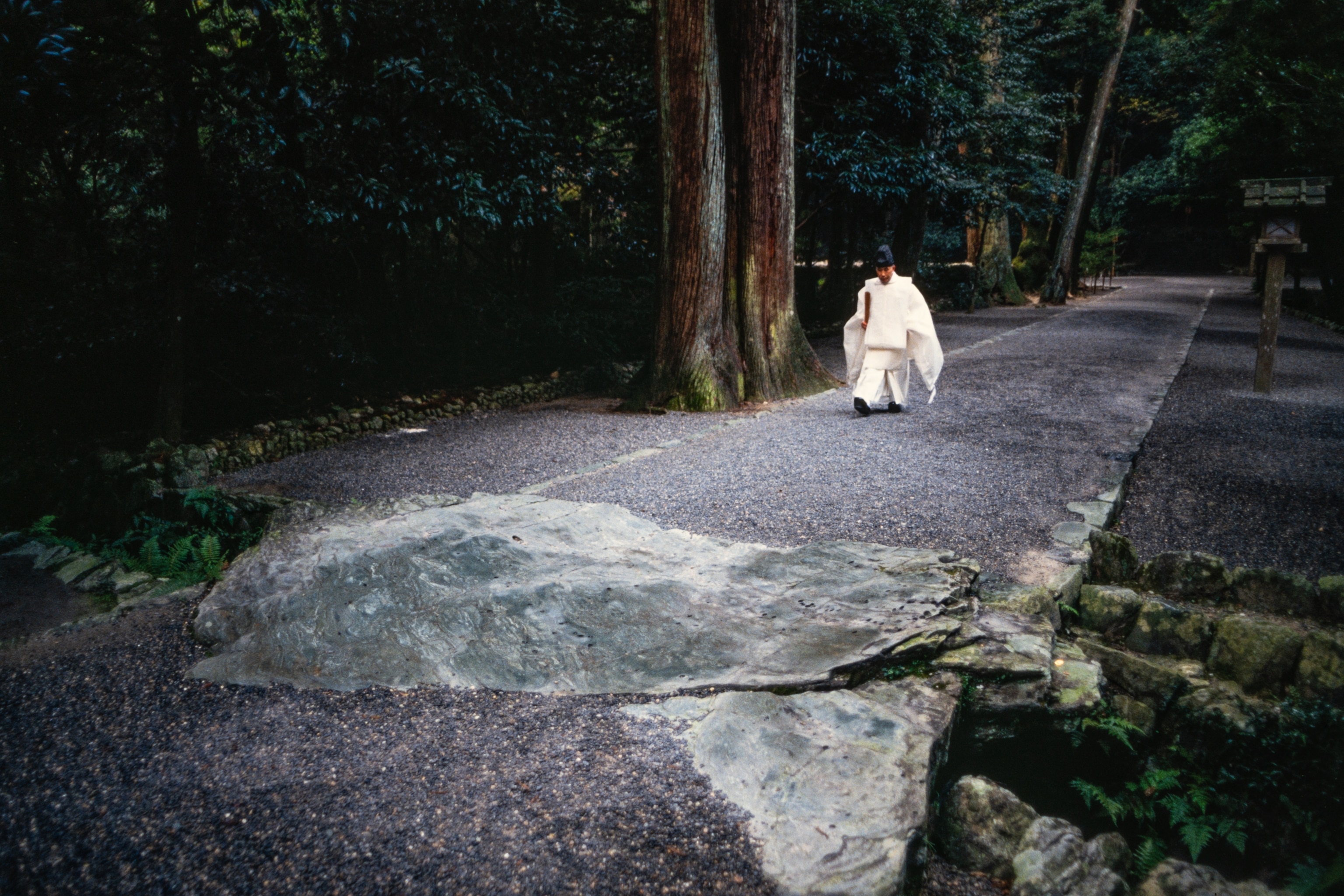

Yamashita’s focus was Ise Jingu, a roughly 2,000-year-old shrine that is considered the holiest in Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion. He went in search of a patch of small white stones marked off by wooden posts and rope. In the Shinto belief, deities inhabit stones, trees, mountains and other objects of the natural world. It would be a far cry from the lush gardens of the West that have been depicted in 19th century paintings by the likes of John Constable, Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet.

In another precinct of the shrine, he came across a different stone – large and red and deliberately placed among small rocks, in the middle of a courtyard – possibly another example of the belief in deities inhabiting natural objects. “You sit and contemplate it. It can mean different things to different people. In my view, the Japanese garden is about your imagination – what do you imagine that is?” he says.

Perhaps more than any other place in Japan, Hokkaido, the northernmost prefecture, has exerted the strongest pull on Yamashita. It was the subject of his first story for National Geographic, published in January 1980. He has returned many times, most recently during winter in early 2020 – his last overseas trip before the pandemic halted travel – for whooper swans and red-crowned cranes in Akan-Mashu National Park and Hokkaido’s highest peak, Mt. Asahidake, in Daisetsuzan National Park.

At Mt. Asahidake, he had to wait two days for strong winds to die down before it was safe to ride the ropeway to the base of the peak. “I’m up there and the sun is beautiful,” he says. Which is not to say that he had it easy. To capture the shots that he wanted of “big snow” and trekkers and fumaroles belching steam and sulphurous gas, Yamashita had to strap on snowshoes and hike his way up. “The snow is deep and you’re sucking wind because you’re really high up there” – more than 7,500 feet (2,280 meters) above sea level, he says. The mountaintop is close to one of Yamashita’s favorite places, Asahidake Onsen, a tiny settlement (now part of neighboring Higashikawa town) of lodges and hot springs.

On his trip, Yamashita also squeezed in a few days of photographing whooper swans and red-crowned cranes around Akan-Mashu National Park. Many of the pictures that he took convey a sense of extreme cold that comes from what he calls the “blue hour”. “The sun has set. The light comes from the sky, turning this snow a blue tint which gives you a real sense of the cold. I love this blue light,” he says. “This is why I come to Hokkaido.” It’s the kind of breathtaking scene that National Geographic has repeatedly turned to Yamashita for. “My roots are all about Japan. My first story was Japan – and it continues to be a place that I return to.”