Discover the art behind Nashville's signature sound

In Music City, country music and old-school letterpress design have long harmonized.

On an early Sunday morning in January, Nashville’s Lower Broadway—“Lower Broad” to locals—looks like the day after a zombie apocalypse.

Doors all along the street are now shut beneath unlit neon signs, more than a few in the shape of guitars. Some of the best but lesser known country musicians played these venues last night in the coveted after-10 p.m. Saturday slot. But, as is increasingly the case, many went unnoticed among the growing number of raucous bachelorette parties and conventiongoers. Nashville is booming; about a hundred people a day are said to move to this iconic Tennessee city, and the visitor count is approaching 15 million annually, with record increases year after year.

I try to conjure the riotous scene along this strip just hours earlier: pounding music, neon, visitors spilling out of bars. For many, the now desolate streetscape would mean one sad thing: The show is over. For me, however, and what I’m looking for, I’m right on time.

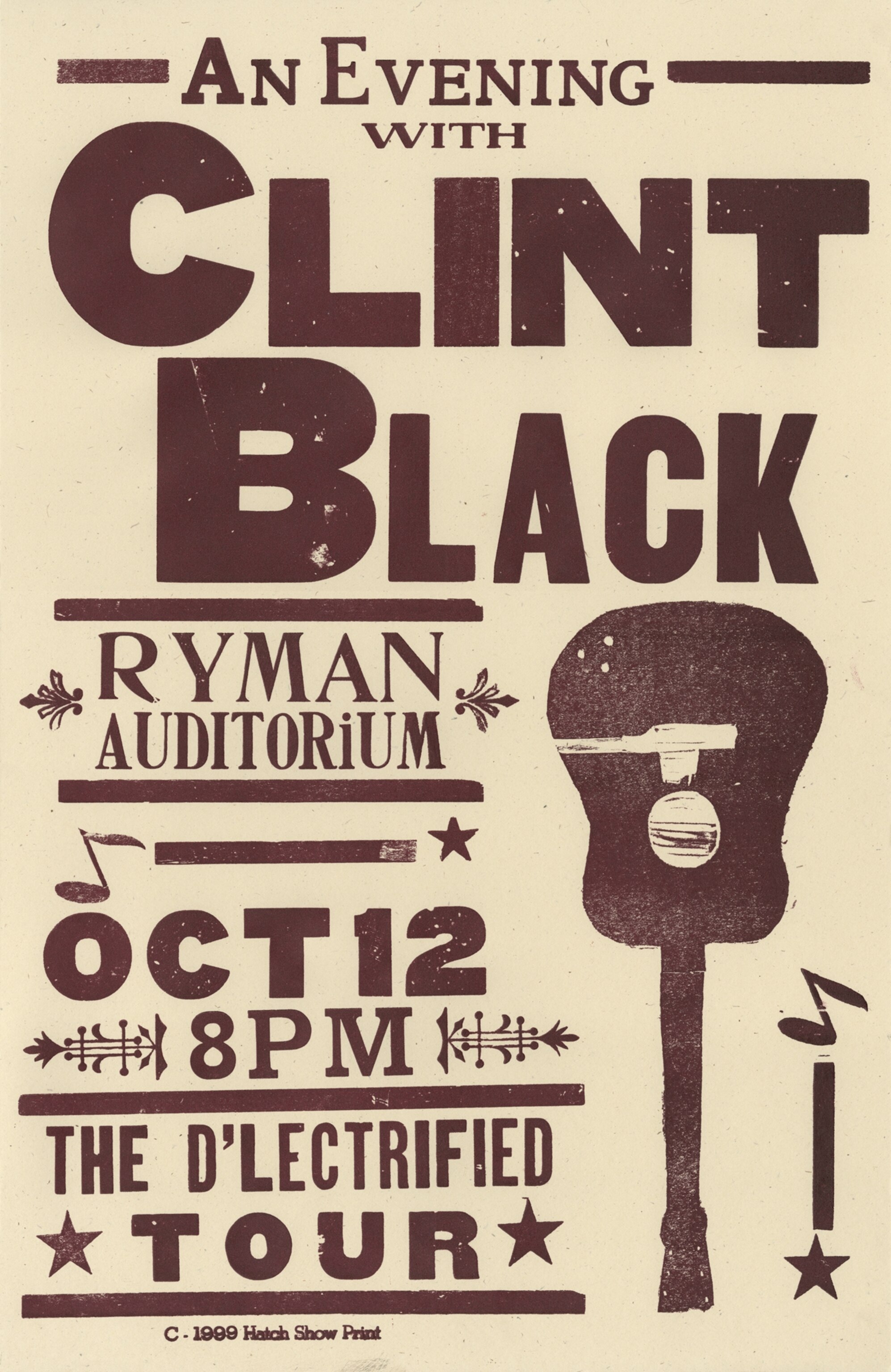

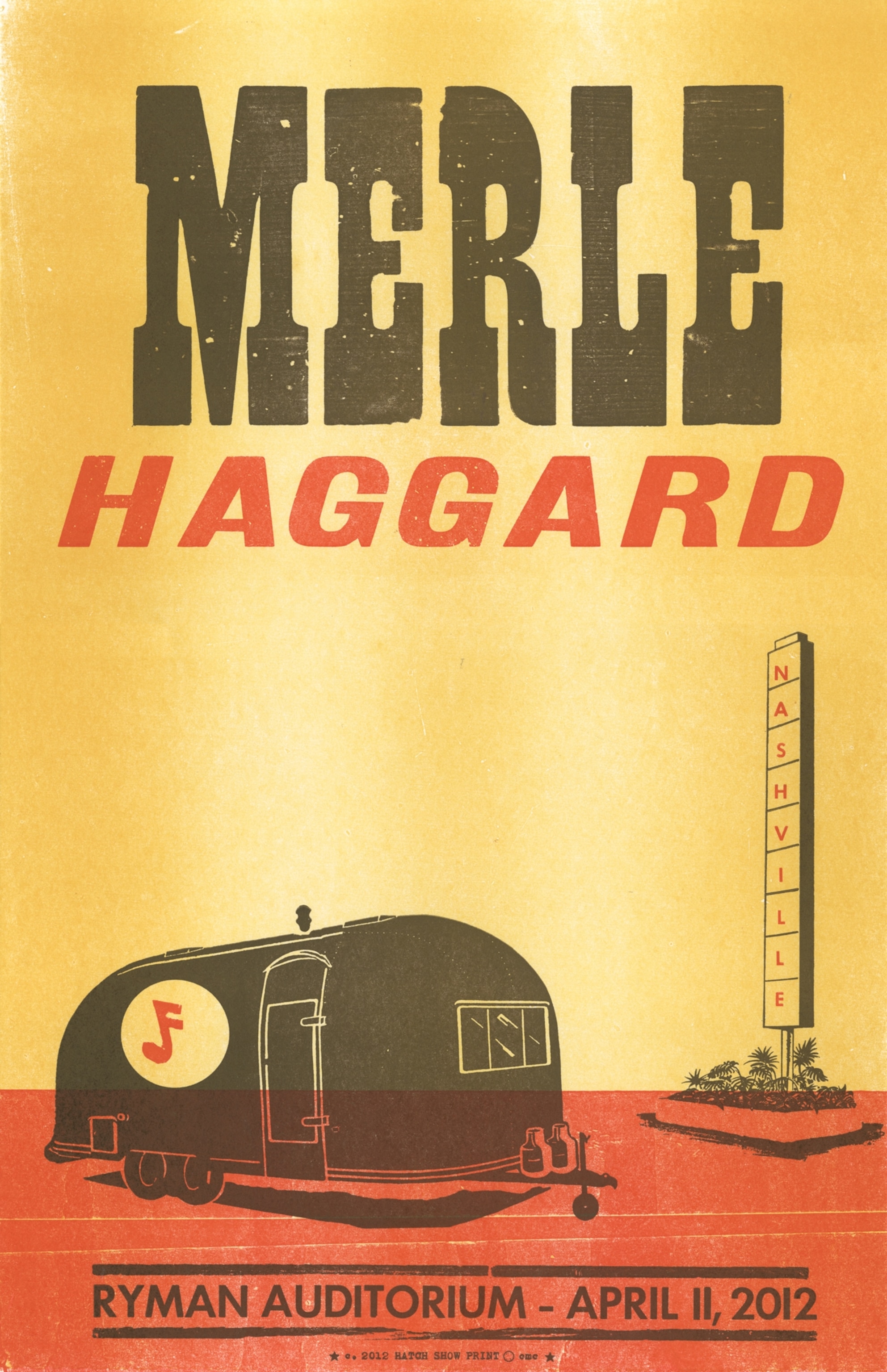

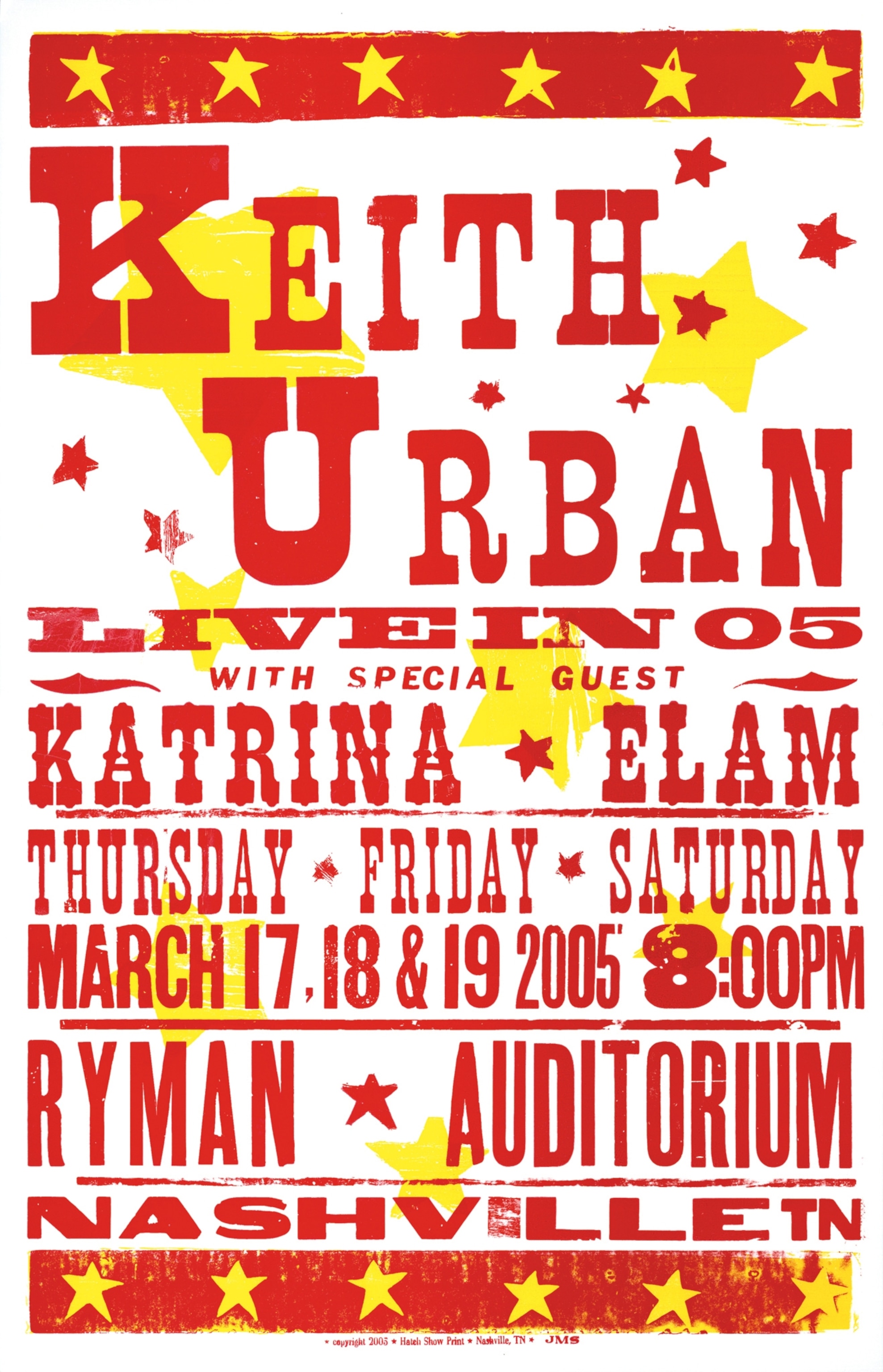

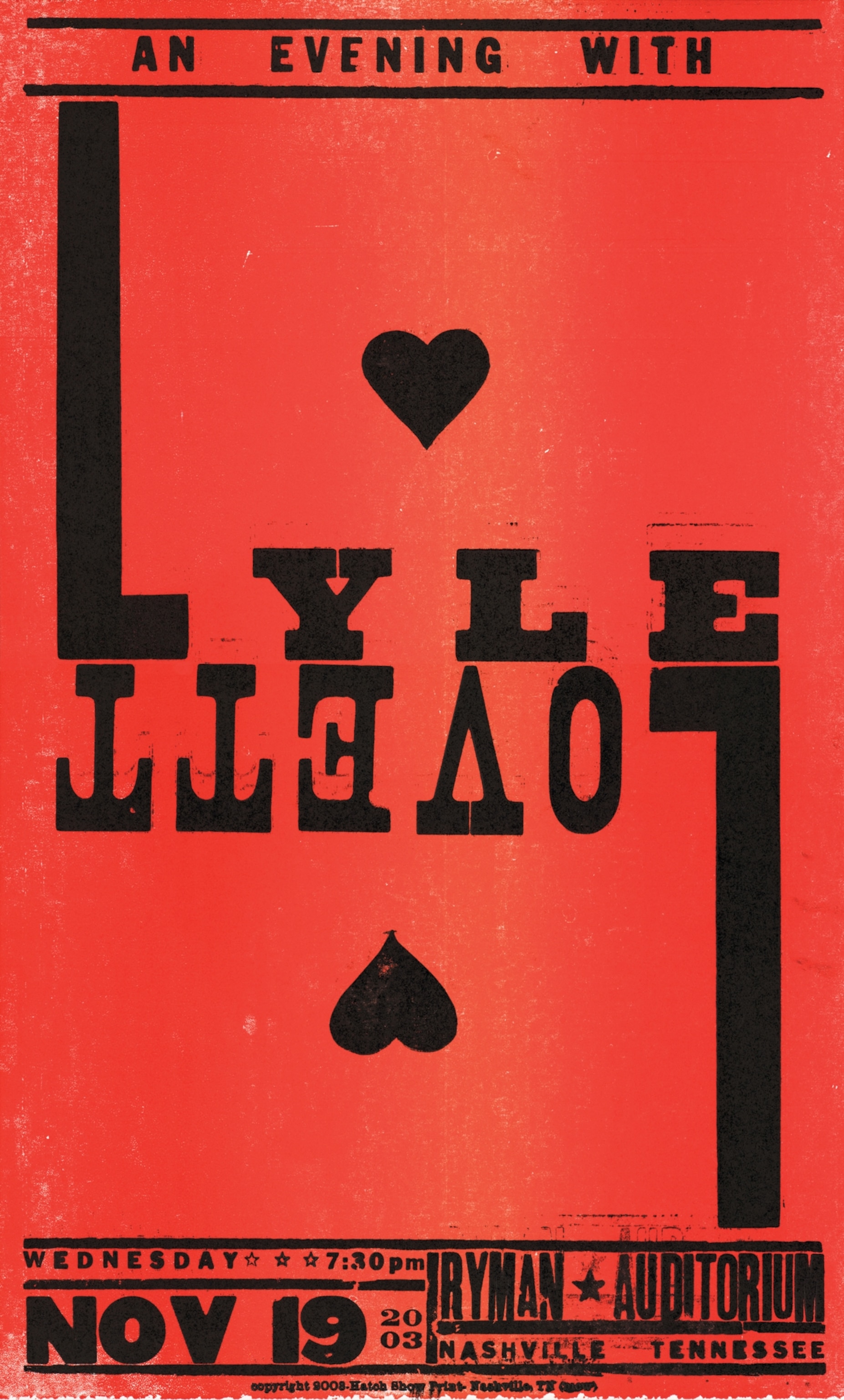

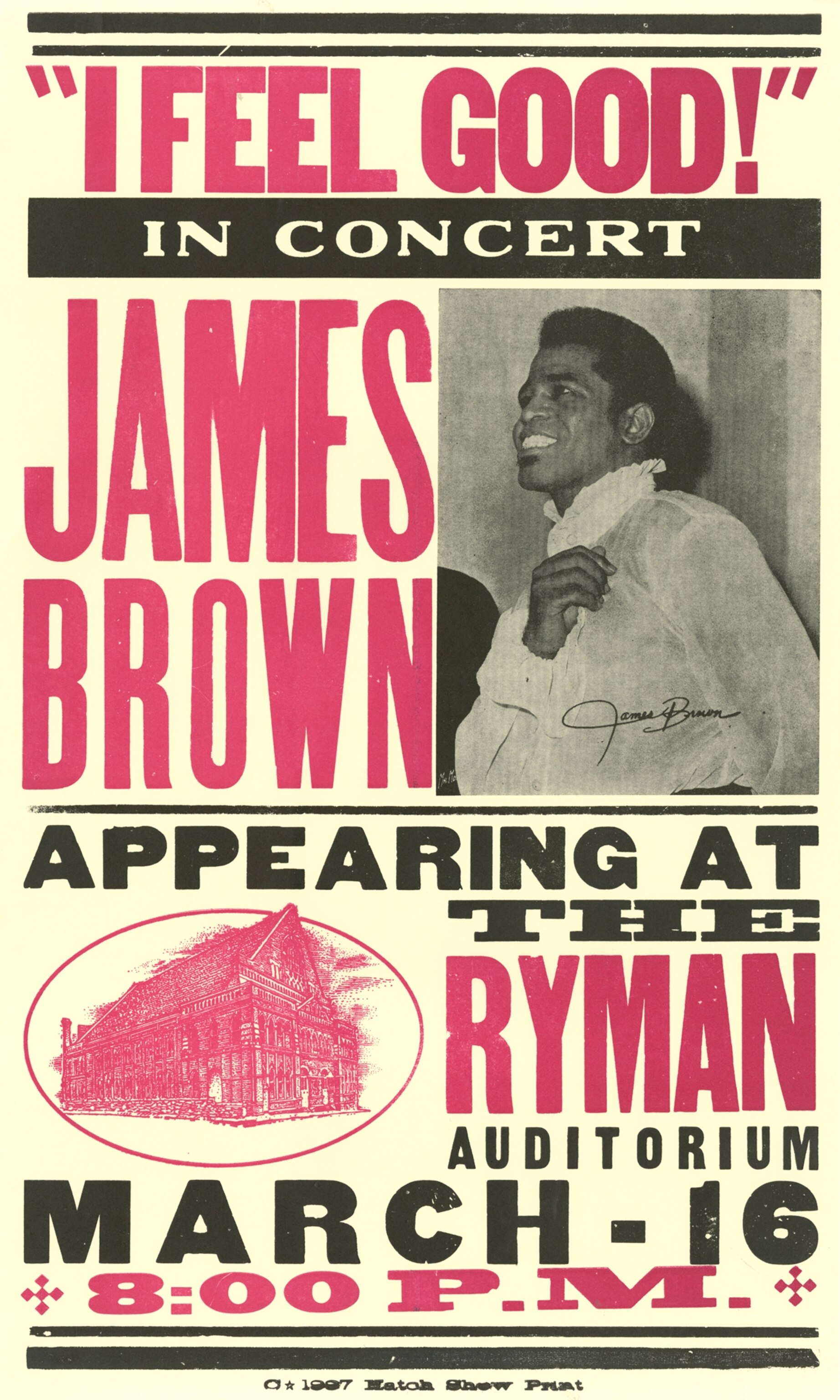

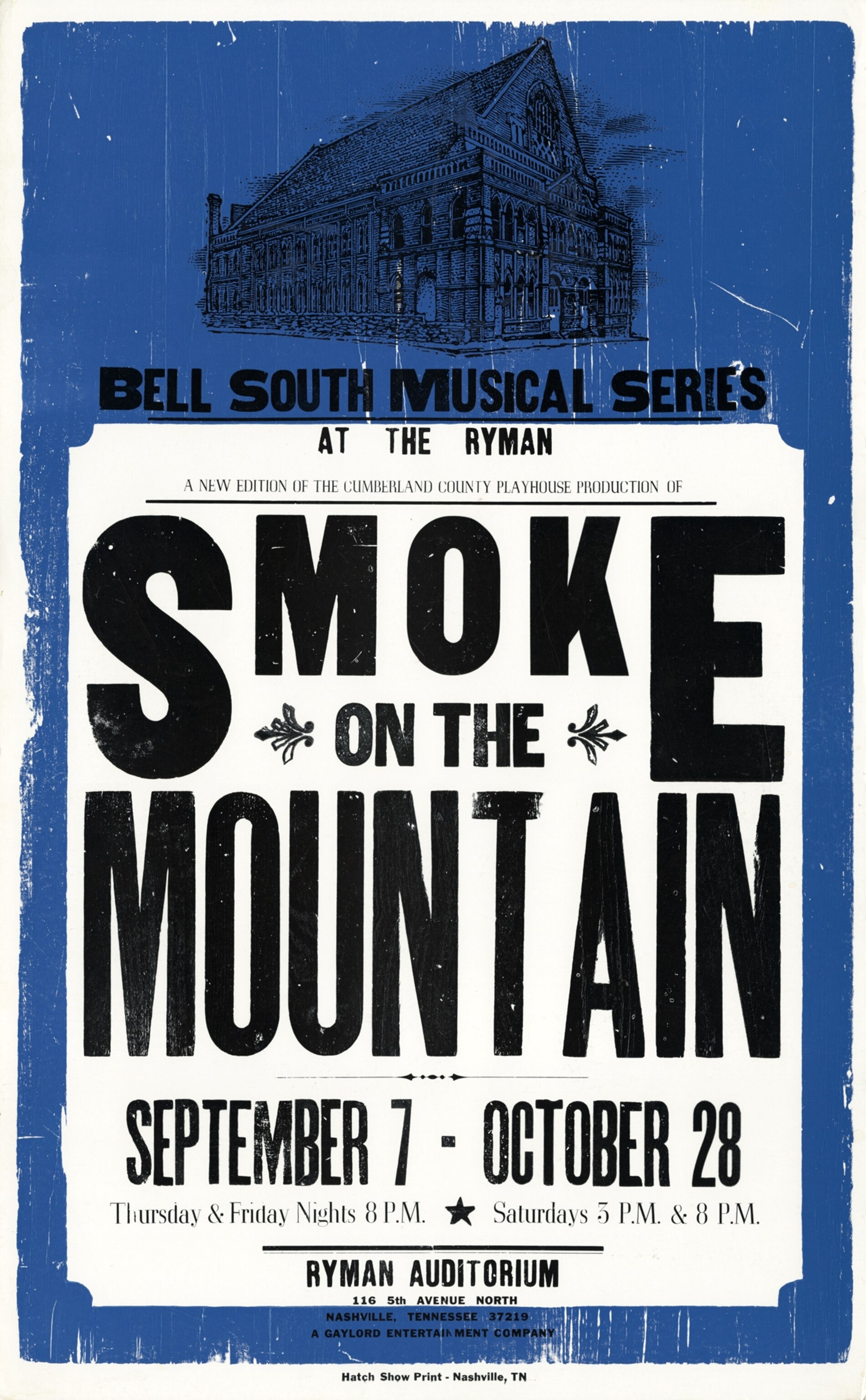

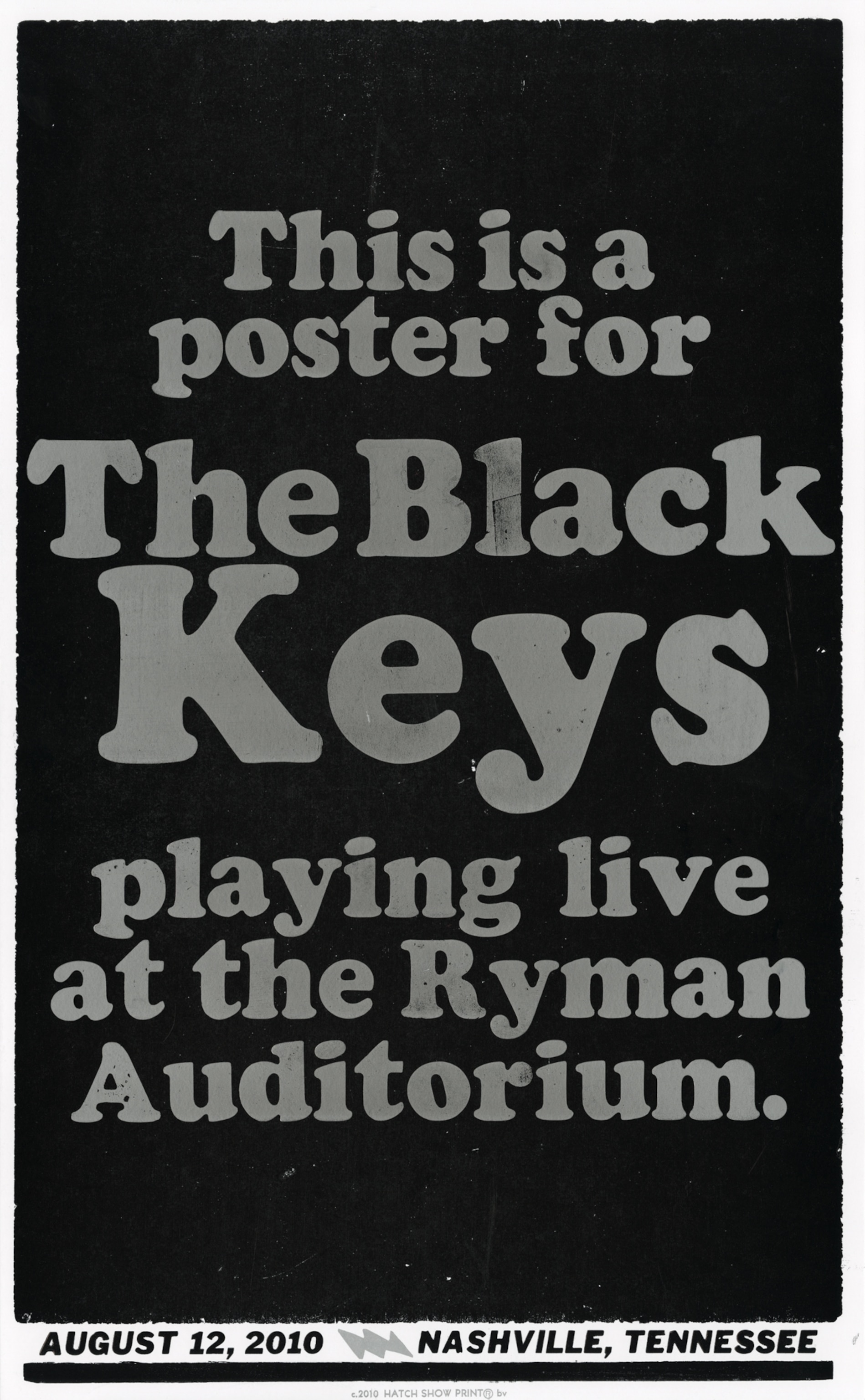

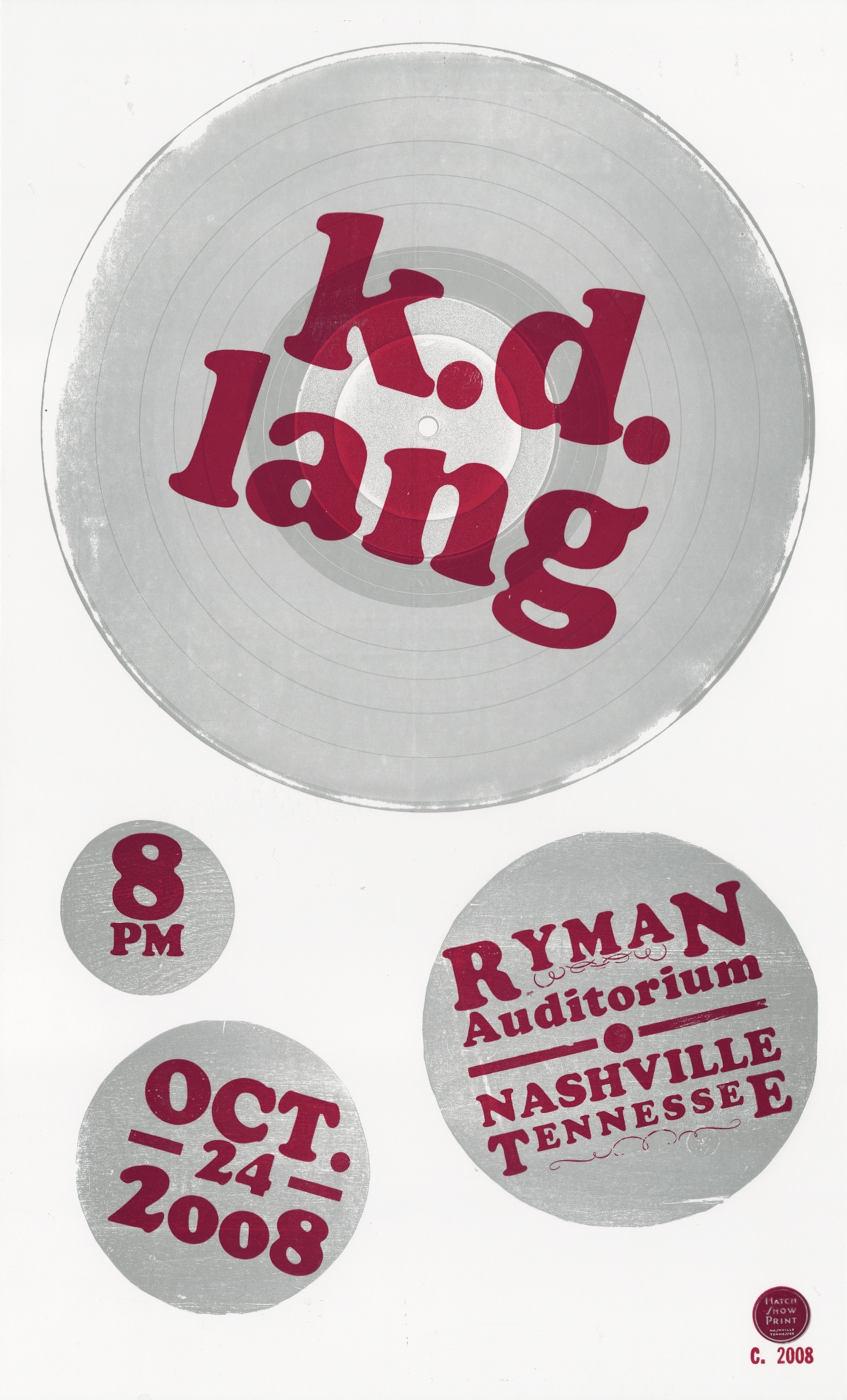

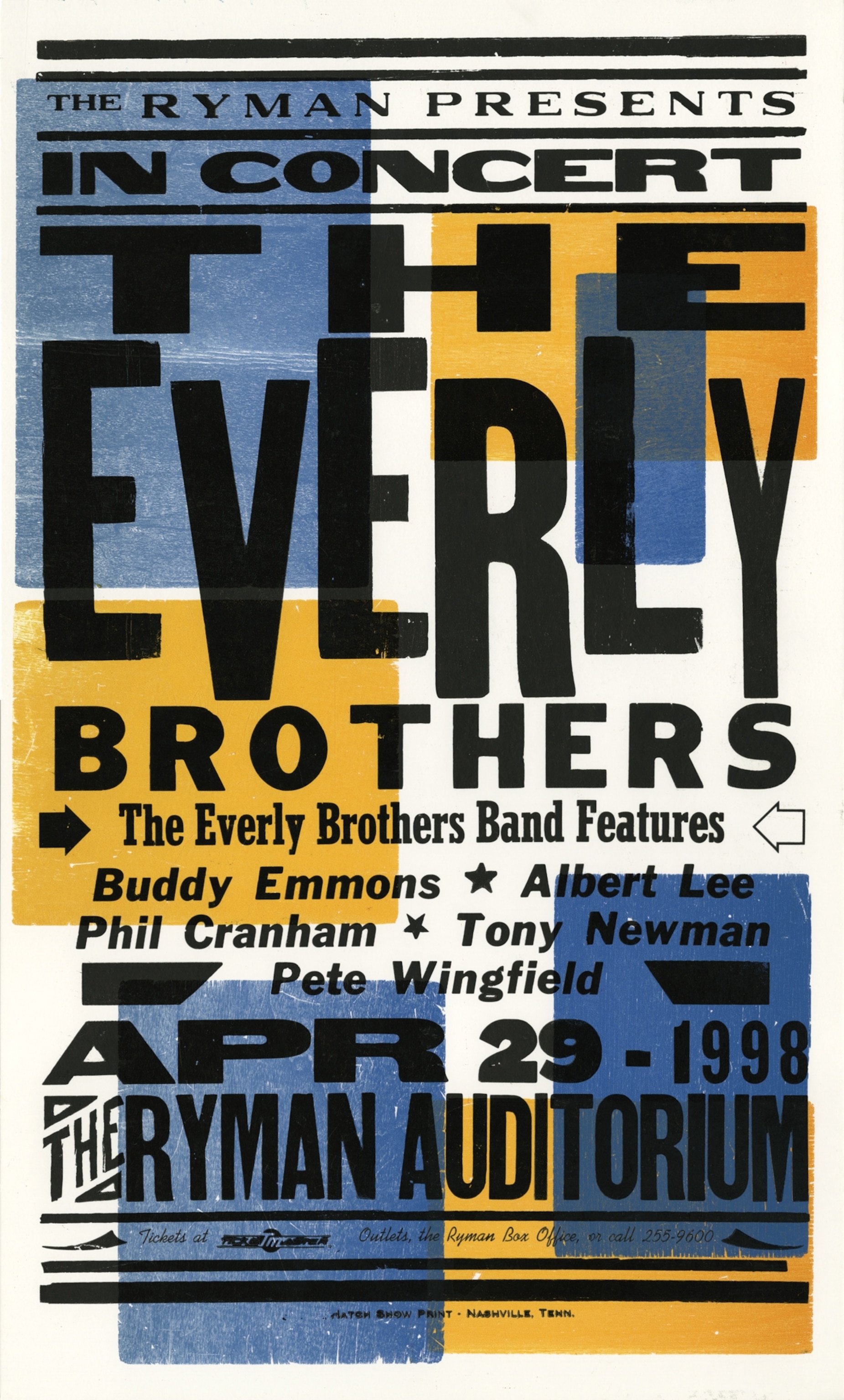

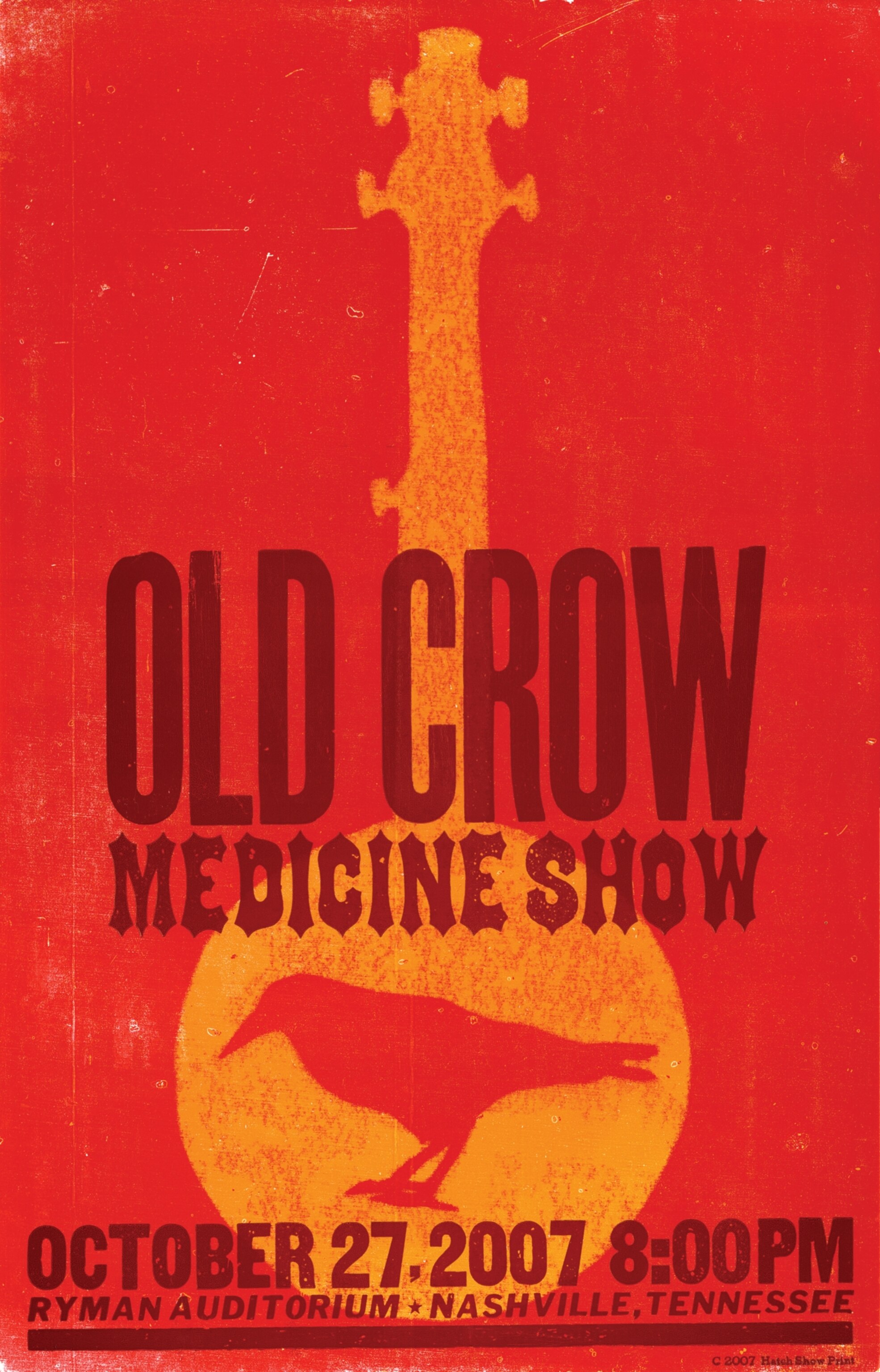

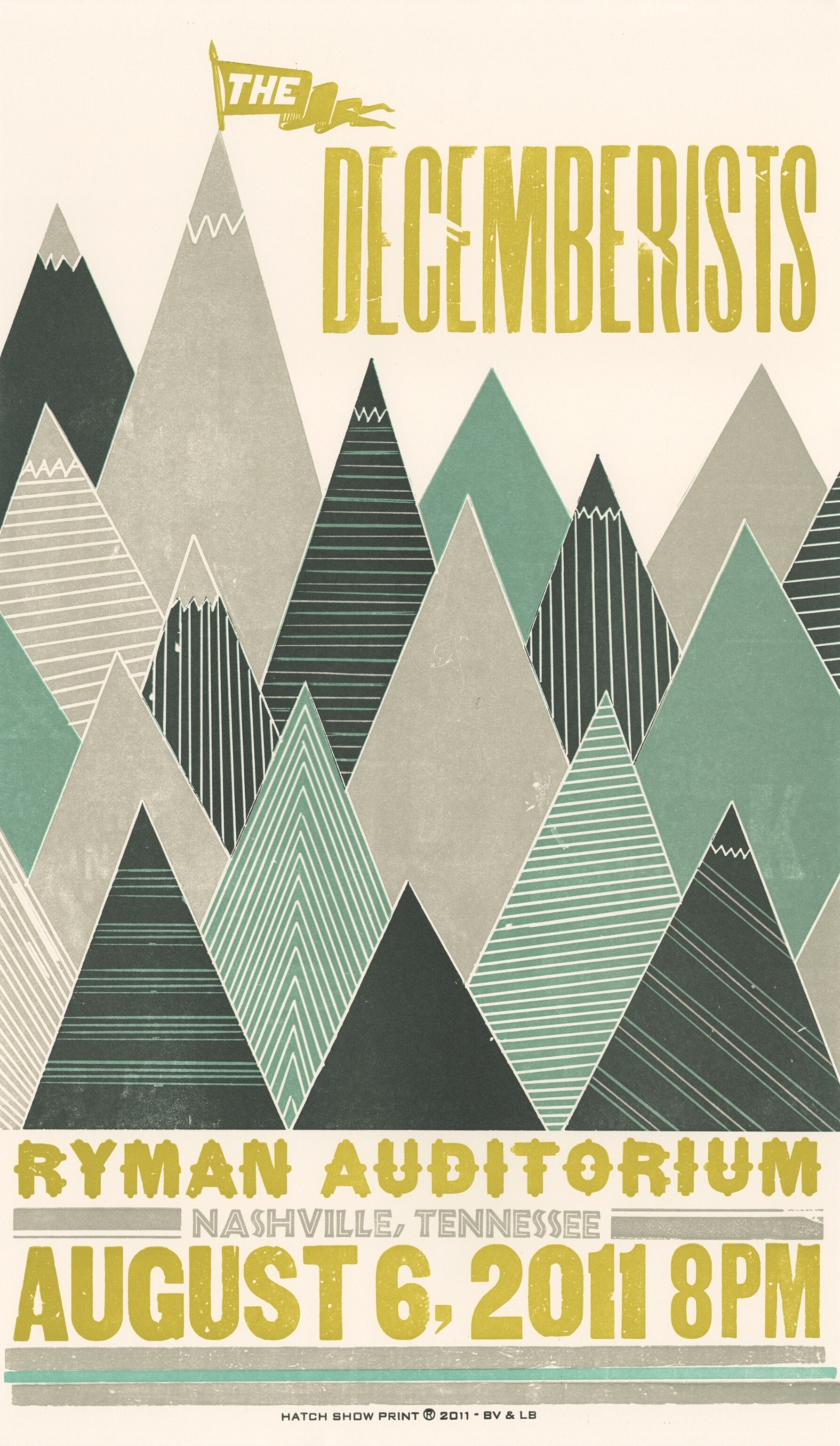

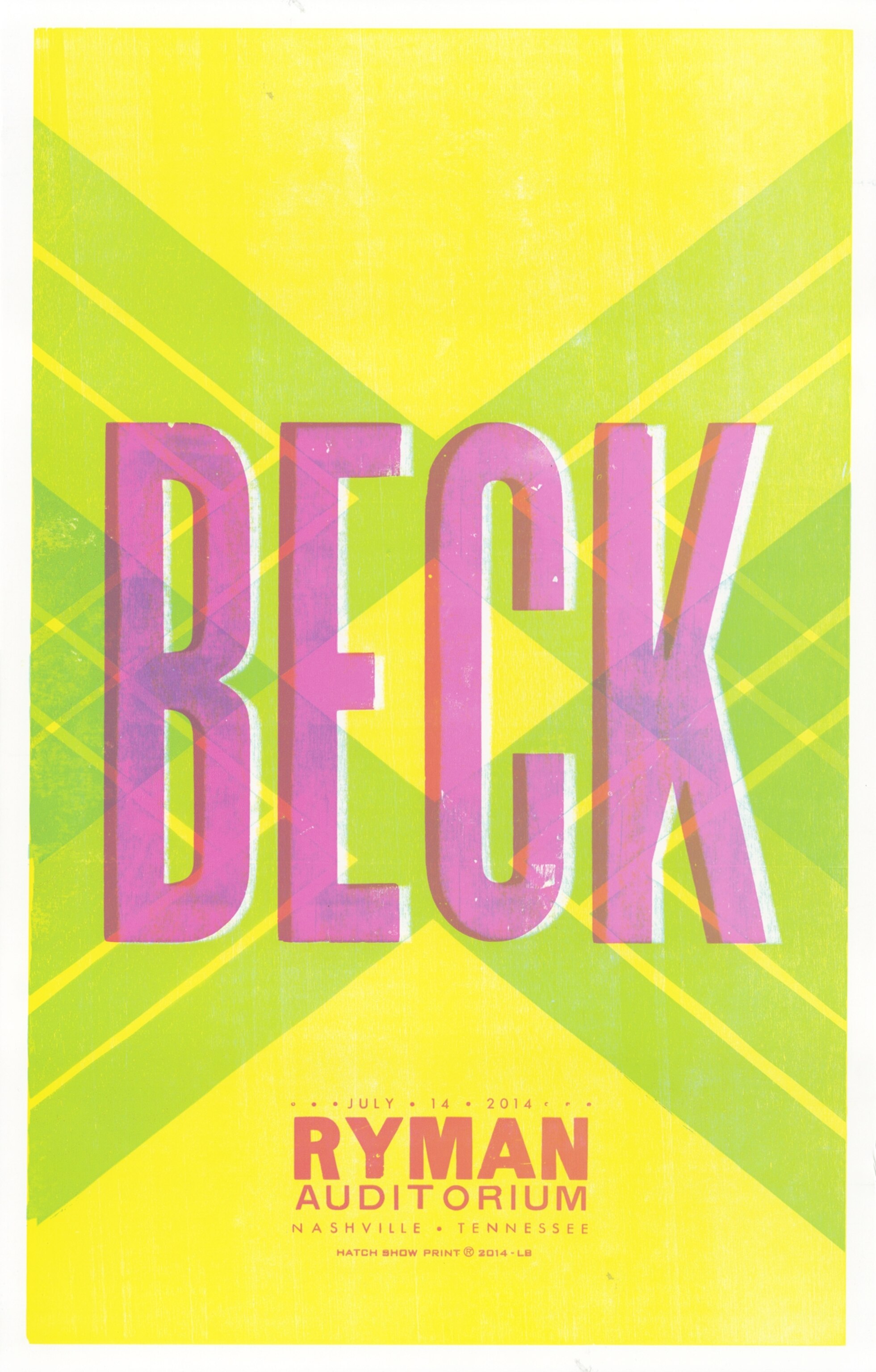

Hatch Show Print posters

By noon, I stand on the shop floor of Nashville’s Hatch Show Print, one of the oldest running letterpress shops in North America. Hatch opened its doors the year Thomas Edison invented the incandescent light bulb. While nearby shops printed newspapers and Bibles, Hatch hitched its future to the 20th-century birth and evolution of country music, and eventually every music genre. Hatch presses have pumped out show posters for everyone from Hank Williams, Jr., and Dolly Parton to Paul McCartney, Led Zeppelin, and the Beastie Boys—every run using movable-type technology dating back to the era of the Gutenberg Bible. As the owner of several milk crates of vintage vinyl, I revel in this analog mother lode of Nashville lore.

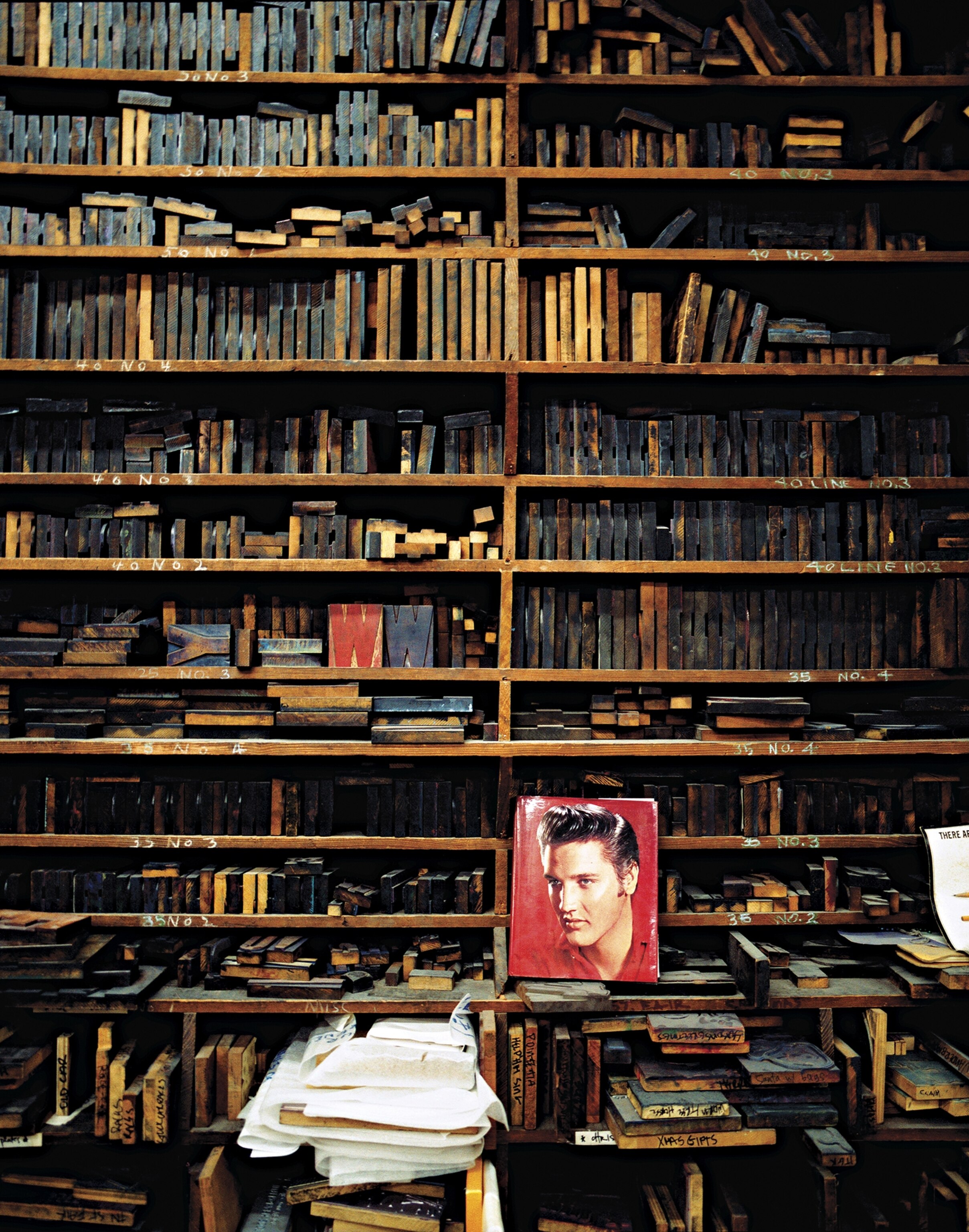

To my right a 1960s Vandercook press, the size of a sideboard, is covered with celebrity signatures from the likes of ZZ Top and “Weird Al” Yankovic. Across the room, a 60-foot wall of warped and crooked shelves holds almost 14 decades of metal and wooden type blocks alongside carved images of past customers such as Herbert Hoover and Anderson Cooper. Finished works serve as wallpaper.

“We’re a constant here,” says Hatch shop manager Celene Aubry. “We’re telling the story of how the city changes, how the country changes.”

It’s Sunday, so I can only imagine the cacophony of clickety-clacks, thuds, and whirs of full production mode. There are 10 different makes and vintages of presses, including a Sigwalt Platen from 1896. Each poster is unique—the density of ink, how it transfers to the paper. It’s all done by hand, locking in the type blocks, cranking each page through, one sheet at a time, one color at a time. Restrikes of an infamous Elvis poster (once decried by a southern preacher for being too sensual) are made with the exact print blocks of the original run. Even new commissions use vintage type. This attention to detail preserves Hatch’s seminal American graphic character: bold colors, chunky block letters, no-nonsense. It’s a design style many recognize, even if they don’t know it comes from Hatch.

When you go extreme into the digital world, the natural reaction is to swing back to things that are handmade.Celene Aubry, Hatch shop manager

Growing fascination with letterpress, vinyl, and all things analog is no surprise to Aubry: “When you go extreme into the digital world, the natural reaction is to swing back to things that are handmade. We have graphic designers come back to Hatch to reground themselves.”

Hatch’s iron gates and 80-foot-tall wall of glass showcasing the shop’s inner workings remind passersby that Hatch is a working museum. The best way to find its mark on Nashville today is to talk to the locals. [Take a family trip to Nashville.]

“It’s like hot and cold running water. Show posters are just part of our culture here,” says former Hatch trainee Bryce McCloud. McCloud is 43, tall, slender, with a salt-and-pepper beard and smiling eyes. A sculptor and 21st-century letterpress master, McCloud opened his shop, Isle of Printing, in 1997 in an edgy downtown enclave nicknamed Pietown, a slice-shaped neighborhood west of Bridgestone Arena.

Inside McCloud’s strip-mall studio, there’s endless creative clutter. Some call him the Willy Wonka of modern letterpress for his whimsy, his intuition, and perhaps most of all, his unusual business plan.

“The reason I created Isle of Printing was that I wanted to change the world with art,” he says, spreading ink on his Vandercook press. He locks in type blocks and cranks it up. “It’s a bold statement, but you gotta shoot for something.” He pauses, pointing at a smear of magenta pigment across the moving roller. “Hear that? When the ink’s just right, it kinda sounds like sizzling bacon.”

With commercial profits, McCloud commissions himself and a team of other artists to make community art. His project “All Are Welcome” gathered ambassadors from Nashville’s Kurdish, Nepalese, Mexican, Arab, and 15 other ethnic groups, including native Nashvillians. They talked about the concept of “welcome” in their cultures and printed T-shirts that said “welcome” in their native languages. “We wanted the gringos, so to speak, to be wandering around in T-shirts that said ‘Welcome!’ in Arabic,” says McCloud. His many community art ventures share similar motivations.

Art, McCloud thinks, can unite Nashvillians, helping them share and expand their world, without abandoning who they are. “The recent growth in Nashville is breathtaking,” he says, but “losing community is one thing we’re all afraid of. The best thing about Nashville isn’t the buildings; it’s the culture of people.”

Amid massive growth and change, locals sometimes pine for the days when you could just show up to venues such as The Bluebird Cafe for a quick beer and a fix of bluesy talent, with no line out front to get in. I discover it’s still possible to catch a bluegrass Grammy winner inside the scruffy Station Inn on a Monday night. Wall-to-wall yellowed show posters surround the half-full room of locals—reminders of 44 years of concerts on this Gulch neighborhood stage. Phones lie face down, and conversations stop as the music starts.

Nashvillians understand. A live performance is a singular confluence of time, place, musicianship, and audience—never to be repeated. But neither will it be forgotten. Because plastered somewhere, there’s a show poster to remember this night forever.