Remember the Alamo? A battle brews in Texas over history versus lore

A plan to rethink San Antonio’s “cradle of Texas liberty” includes raccoon-hatted heroes, a rock star, and lots of controversy.

“What happened at the Alamo again?” asked my cousin, who was visiting from Missouri. It was sometime in the early 1990s and we were in San Antonio, lined up to see the best-known tourist attraction in Texas.

As we passed through arched wooden doors into the 18th-century mission chapel, my sister piped in: “This is where Mexican general Santa Anna tried to take Texas back from Davy Crockett!”

Of course, that wasn’t quite right. My sister and I grew up in San Antonio, but she may have been out sick the day her seventh-grade Texas history class covered the Battle of the Alamo. Like many locals, she bought into the narrative of freedom-fighting Texans versus villainous Mexican soldiers. As a kid in the late 1970s, I subscribed to that story too, even begging my mother to buy me a facsimile of Crockett’s coonskin cap at the Alamo gift shop.

The 1836 conflict actually took place in what was then Mexico. Anglo settlers, lured to the steamy, snake-filled state of Tejas by the promise of farmland and autonomy, were rumbling for independence from the increasingly centralized Mexican government. Nearly 200 of these Texians (as both Anglo and Hispanic rebels were known) occupied the ruins of Mission San Antonio de Valero, nicknamed “the Alamo” after the Spanish word for cottonwood.

Outmanned and outgunned by the Mexican army under President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the rebels were nearly all slaughtered, their bodies burned on pyres in the adjacent plaza. The Texians lost that battle, but soon after won their war for independence after defeating Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto and cementing the newly formed Republic of Texas in April of 1836.

But the narrative conflict about what happened at this “cradle of Texas liberty” was far from over. A complex argument of facts versus fiction, right versus wrong, and what the battle was even about hasn’t let up since, even as Texas became a U.S. state in 1845 and ensuing decades saw San Antonio turn into a majority Latino city. No wonder my sister didn’t have her story straight.

Now, an ambitious $450 million plan to restore and recalibrate the UNESCO World Heritage Site has spurred a new battle over how to remember the Alamo. The Alamo Plan puts forth expansive, expensive ideas: Preserve the fragile chapel; close surrounding streets to car traffic; build new museums to tell the site’s centuries-long history and to house artifacts, including a cache donated by rock star Phil Collins. But it’s all become obscured in a fog of politics, claims of poorly authenticated relics, and gun-toting protesters. It’s a story as big—and as messy—as my home state.

A plan to remember the Alamo differently

For a place mythologized in film and song, the Alamo can seem tiny and underwhelming to first-time visitors. The limestone walls of its chapel and adjacent Long Barrack (site of much of the fighting) are crumbling. Museum space is limited to a one-room, 1,800-square-foot building; history is mostly recounted in the surrounding gardens via mounted plaques and a short film.

What monuments to the Confederacy coming down means for the U.S.

Another surprise: The distinctly gabled chapel sits in the center of San Antonio’s bustling main square, Alamo Plaza, not in a tumbleweed-filled battlefield. It faces a ragtag block of 19th- and early-20th-century buildings holding a Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, souvenir shops, and a wax museum recently in the news because visitors kept punching its Donald Trump dummy. On land where Mexican and Texian fighters fell, I remember setting off New Year’s Eve firecrackers with high-school friends and slurping raspas (snowcones) from stands which operated in the shadow of the Alamo until very recently.

“The Alamo is boring, frankly,” says Austin writer Chris Tomlinson, coauthor of the new book Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. “The average visitor spends less than 15 minutes there; patrons across the way at Ripley’s or the Tomb Rider 3D ride stick around for 45 minutes, and they buy a hot dog! The Alamo is this fascinating place to think about justice, liberty, white supremacy, and other issues, but it isn’t being presented that way.”

Learn why Texas has such an independent streak.

The Alamo Plan was conceived in 2015 by state and city forces and the Alamo Trust, the nonprofit which manages the site. Its goals: Preserve the buildings and grounds and make the stories they tell more accurate. “We want to bring them in with the events of 1836, but expand from there,” says Alamo Trust Executive Director Kate Rogers. “To a lot of people, the Alamo is an enigma. Maybe they know the battle, but they don’t know the place’s history as a mission or how San Antonio grew up around it.”

Besides shoring up the original limestone structures and erecting a state-of-the-art visitors’ center and museum to showcase artifacts (including 400-plus donated by Collins), the original Alamo Plan involved changes meant to reclaim the mission-era footprint and bring a sense of reverence to the plaza, which is both a battle site and a graveyard for fighters on both sides as well as Indigenous mission residents.

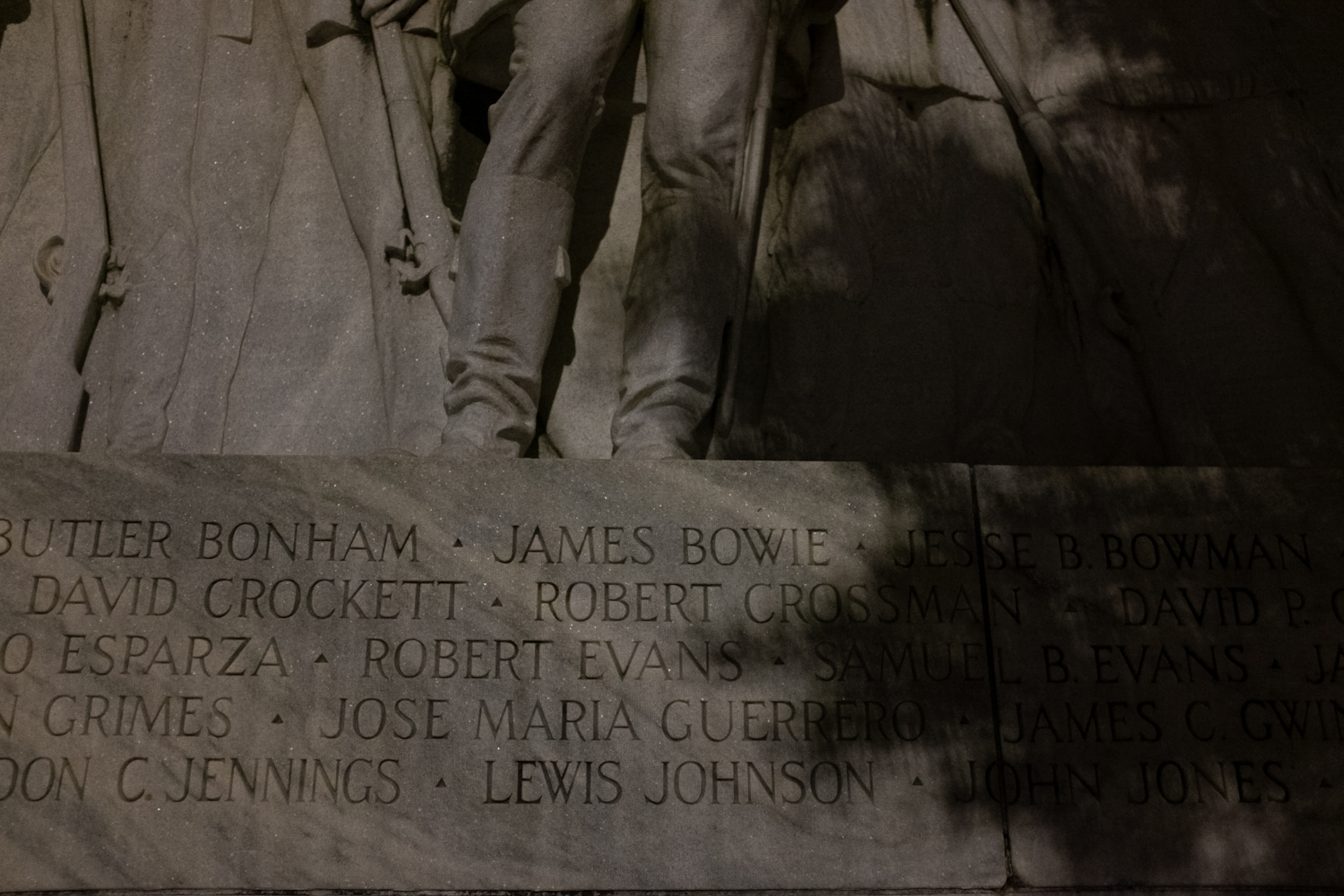

Other proposals would have closed surrounding streets to cars, erected exterior glass barriers to delineate the original mission grounds, and relocated a 60-foot-tall stone monument to the Texian fighters (usually called Defenders) from one corner of Alamo Plaza to the other. The last, known as the Cenotaph, holds names and bas-relief sculptures of Defenders including the “holy Trinity”: Crockett, Commander William Barret Travis, and Jim Bowie, a famed fighter, slave trader, and the probable inventor of the Bowie knife.

Controversy surrounds the ‘cradle of Texas liberty’

Texans take Alamo lore and legends seriously. My childhood best friend, whose great-great-great-great-grandfather died at the Alamo, would playground brag that her family was braver than mine. When I visited the Texas State Capitol Building in Austin as a teenage government geek, I was fascinated by the outsize 1905 painting “Dawn at the Alamo,” depicting Travis and Crockett heroically fending off menacing Mexican soldiers.

“It has become like a religion for some people,” says Indigenous multimedia journalist Robert Pluma, a descendent of an Alamo Defender. “You find conflicting narratives, and you need to preserve them while examining the fissures.”

It’s no surprise that the Alamo Plan’s proposed changes have ignited ongoing debates, political posturing, and even armed protests. Historians seek a more nuanced story about why the Texians were fighting (yes, for freedom, but they also sought the right to keep their slaves, then illegal in the rest of Mexico). Indigenous Americans want recognition for the mission era and their ancestors buried onsite.

And traditionalists, many descendants of the Defenders, vehemently oppose moving the Cenotaph. “It’s our headstone, since we don’t have a cemetery to go to,” says Lee Spencer White, founder of the Alamo Defenders Descendants Association. “We want the graves of the heroes to stand out in front of the fort they defended.”

Pluma and other Indigenous and Latino residents see things differently. He’s currently working on a photo, video, and oral-history project documenting the nearly forgotten Indigenous history of San Antonio’s missions (including San José, where his ancestors lived). The Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation, a consortium of local Indigenous groups, has filed lawsuits asking for the Alamo to recognize its onsite cemeteries and for the right to worship inside the chapel.

“The Alamo is a symbol of greatness to some people; to others it’s a symbol of Anglo dominance that is a dark side of our history,” says Scott Huddleston, a veteran reporter covering the Alamo for the San Antonio Express-News. “This plan seeks to address those issues like slavery and the Mexican perspective.”

Still, many people want the old good-guys-versus-bad-guys story: no doubts or additional facts needed.

A legend is born

As usually told, the Battle of the Alamo falls into an archetypical heroic narrative of scrappy rebels rising up against a better-equipped-but-villainous force. Legend holds that the Texian fighters died to buy time for General Sam Houston and the new Texas Army before their eventual victory at San Jacinto. Never mind that this isn’t true. Plus, the mission wasn’t on their land, some of the fighters were slave owners, and Mexico itself was struggling to create a new country.

Still, almost as soon as the cannons stopped smoking, Texans began spit-polishing the history with contested but rousing tales: Crockett went out rifle blazing (some Mexican accounts claim he was captured and executed). All the fighters crossed a line Travis drew on the ground indicating they were willing to die for the cause (most historians say that’s a fable). The Alamo’s iconic, bell-shaped façade served as a backdrop for the battle (actually the U.S. Army installed it over a decade later when the chapel became a storeroom).

(Find out how the bluebonnet became a symbol of Texas.)

“It’s myth making, almost like 1776 was for the U.S.,” says Carey Latimore, a professor of history at San Antonio’s Trinity University who consulted for the Alamo Plan. “Myths sell books and artifacts, but they aren’t real history.”

Depictions of the battle on the big and small screens, from cartoons to Westerns, helped to skew the facts. “One of the reasons that the myths are so entrenched was because of the popular media in the 1950s and 1960s,” says Tomlinson. “These were profound cultural experiences for Baby Boomers, particularly young white men. But Generation Z can smell the rotten fish.”

Texas even mandates that schoolchildren be taught about the Alamo Defenders in heroic language. Earlier this year, a Republican state representative introduced legislation to block the Alamo from mentioning slavery as one of the causes of the Texas Revolution.

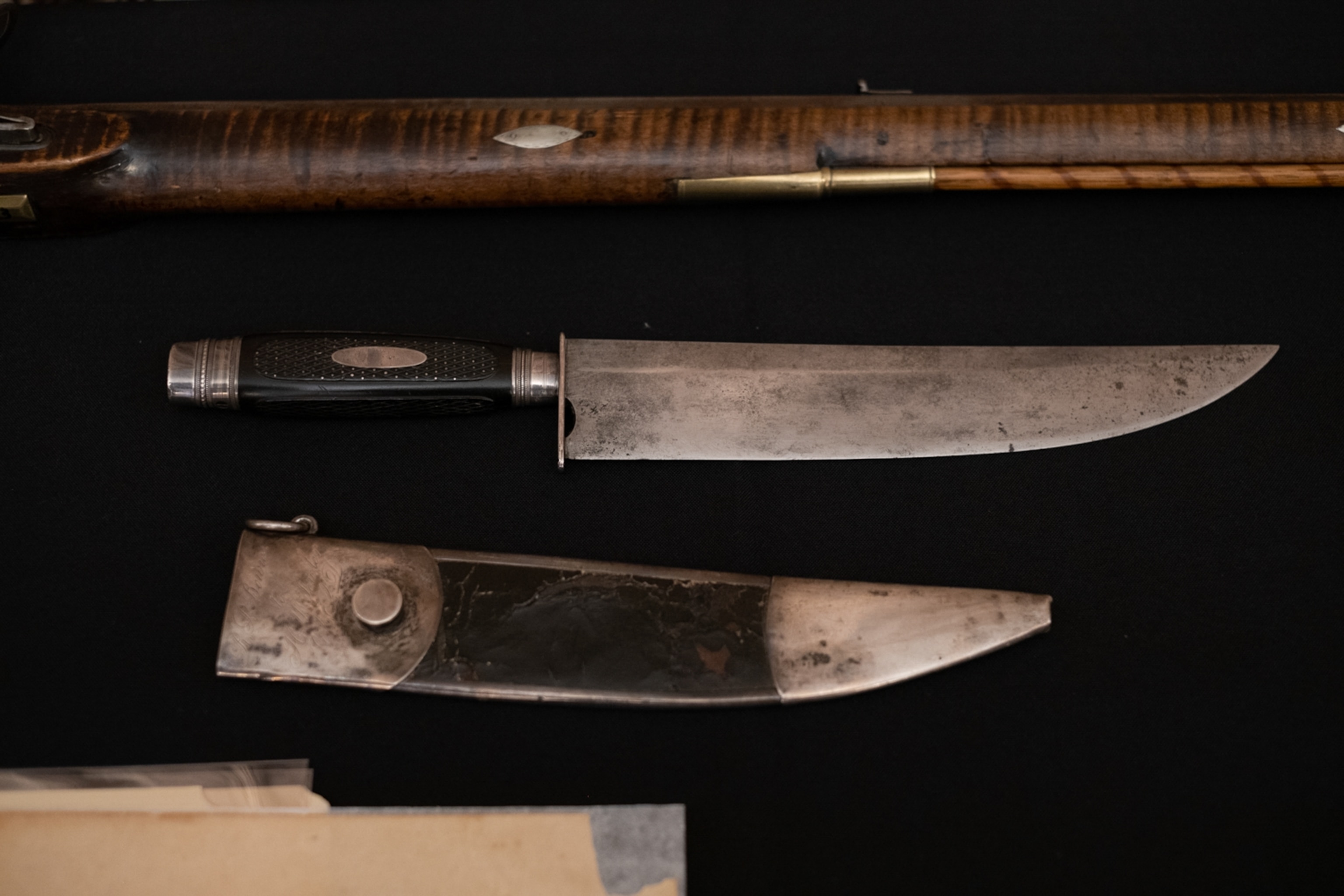

According to many historians, there are also doubts about the authenticity of some artifacts in the Phil Collins collection (reported in the book Forget the Alamo and newsmagazine Texas Monthly). The musician started amassing Alamo-related documents, guns, and swords in 2002. “I don’t know that all of those artifacts have been vetted for their provenance,” says Huddleston.

The authenticity of a rapier-like Bowie knife said to be owned by Jim Bowie was partially confirmed by a psychic; the initials “D.C.” recently—and mysteriously—appeared on a rifle that the Collins collection hints belonged to Crockett.

“The problem is that the Alamo Plan is based on the Phil Collins collection, and some people think it’s just as fraudulent as the Alamo story,” says Tomlinson.

A fuller history

The history of the Alamo isn’t just about the 13-day 1836 siege (and 90-minute final battle). “Focusing just on 1836 means no one talks about the origins of the mission,” says Pluma. “There is so much history connected to these missions that continues to be neglected or deliberately erased.”

The Mission San Antonio de Valero was founded by Catholic missionaries in 1718 in what was then New Spain. It was the first of five missions built in the area meant to convert local Indigenous people by force and to teach them Spanish. They lived, farmed, and worshipped within the stone walls of the Valero complex, which was eventually secularized in the 1790s, its land and buildings given to residents. In the 1800s, as Mexico sought independence from Spain, the mission became a fortress, first for Spanish forces, then for Mexicans, and finally, Texians. During the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, the Alamo turned into a busy U.S. Army storage depot. Today, the five missions form a National Historical Park.

Ideally, the Alamo Plan will find a way to cover not only the famous battle, but also the complexities of these other eras. “It’s more interesting if these ‘heroes’ are shown to be actual men with flaws,” says Latimore. “History is about peeling away layers of myth and getting to what actually was.”

Controversies have come close to halting the project. Major donors to the Alamo Plan dropped out after the Texas Historical Commission denied the city’s request to move the Cenotaph in 2020. Texas Monthly ran a June 2021 cover story about doubts over the Collins collection; the Alamo Trust rebutted that it has meticulously vetted all artifacts.

But this spring, after years of debate, there were small signs of change. Alamo Street finally closed to car traffic after fierce local opposition, meaning the Alamo’s costumed historic interpreters (representing the mission, Mexican, and Texian periods) can now interact with tourists on the plaza. In April, a replica of an 18-pound cannon was installed on a faux adobe rampart; visitors climb up for a Defenders’-eye view of where Crockett and company fired at the Mexican Army. It looks down on the entrance to the present-day River Walk, where I sipped margaritas in college.

The Alamo Trust announced it would break ground this summer on a state-of-the-art exhibit hall, much larger than the current one, to showcase historic artifacts, including the Collins collection. A second proposed space will serve as a visitors center/history museum that will finally dig into all of the eras and issues of the Alamo. Slated to open in 2025—if funds can be raised—that museum will incorporate two historic structures on Alamo Plaza (including a Woolworth’s with significance in Civil Rights-era desegregation).

Many critics say those changes aren’t coming quickly enough, and that the Alamo’s diverse history still isn’t being addressed. “A lot of Texans aren’t ready to reconsider the Alamo,” says Tomlinson. “But nationally, there’s a real hunger to reexamine our foundational myths.”

Jennifer Barger, who is from San Antonio, is a senior editor at National Geographic Travel. Follow her on Instagram.

Robert Pluma is a multimedia journalist descended from San Antonio mission residents and an Alamo defender. His “Hidden Histories of San Antonio” project is supported by the Magnum Foundation and FOTODEMIC. Follow him on Instagram.