Take a hike in Tasmania’s pristine wilderness

The region's natural beauty and distinctive wildlife evolved over millennia.

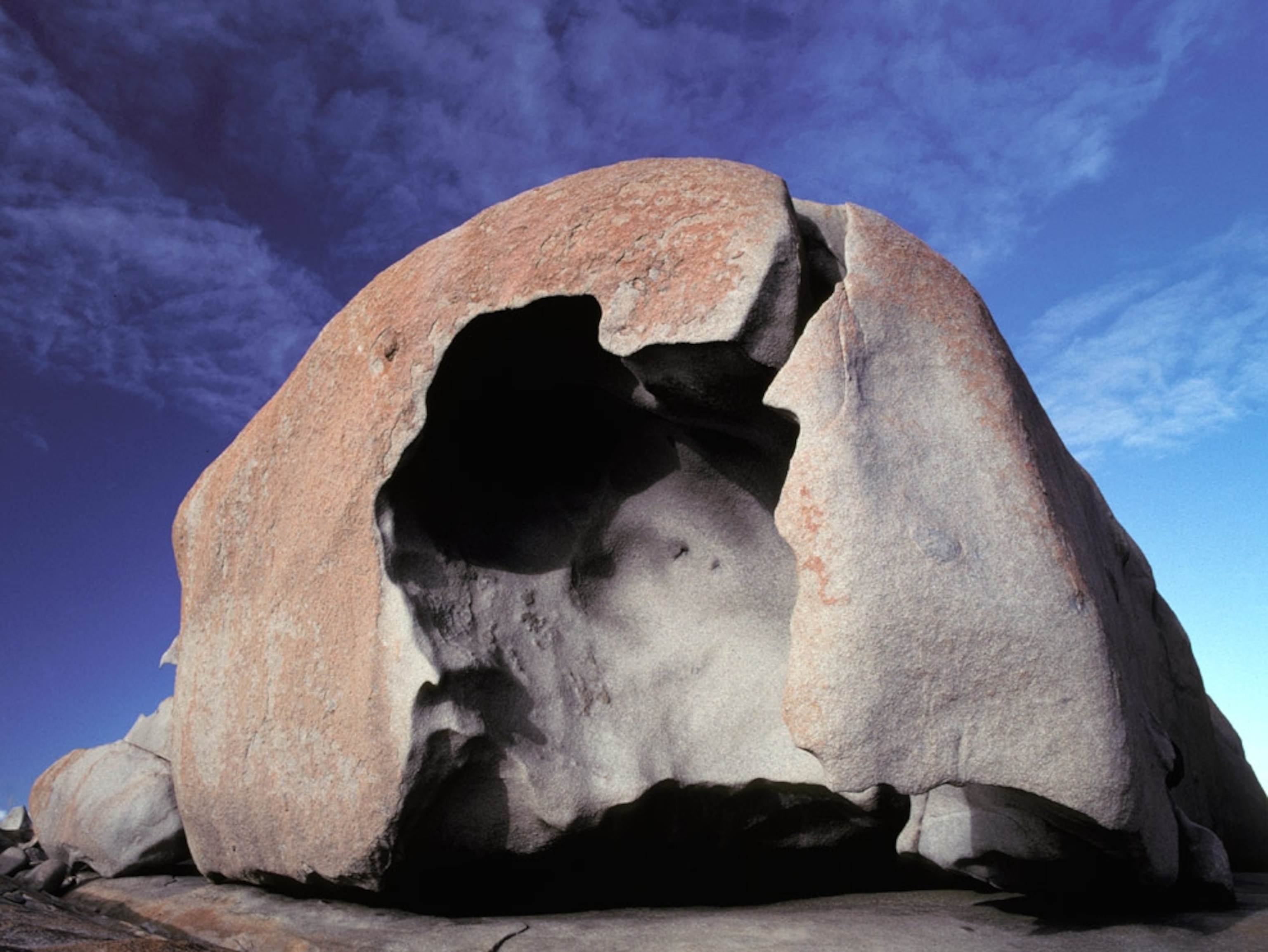

It took millions of years, as well as earthquakes, volcanic activity, continental drift, and extreme conditions—from hot, humid temperatures to ice ages—to create the unique landscape and diverse ecology of today’s Tasmania. Australia’s southern island state is home to one of the world’s oldest and largest pristine tracts of temperate rain forest, as well as untouched coastline, glacial lakes, and impressive peaks. In 1982, UNESCO named a large chunk of the island the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, further expanding its boundaries in 1989. Now it covers almost 3.5 million acres, or about a fifth of Tassie’s total land area.

As well as being an area of incredible natural importance, there is also a significant cultural element to this part of Tasmania. People have lived here for at least 35,000 years, and there are approximately a thousand known Aboriginal heritage sites, including rock shelters, shell middens, and rock art sites throughout the region.

Take a look at a map—UNESCO has cast its net across six national parks linked by conservation areas and reserves. Some have road access; others, like Walls of Jerusalem National Park, with its alpine lakes, dolerite peaks, and ancient pencil pine forests, are so remote that they can only be entered on foot.

Although this can make exploration difficult, the isolation has been a boon for wildlife. Some creatures, like the velvet worm (considered the missing link between worms and crustaceans and insects), have barely evolved for half a billion years. More interesting for the average traveler are the species that appear to have been created in a mad scientist’s laboratory, including incredibly vocal Tasmanian devils, quolls, echidnas (one of only two species of mammals to lay eggs), wombats, and wallabies.

The most accessible part of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, and considered the region’s gateway, is Cradle Mountain Lodge near the entrance to Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park. In the national park, visitors enjoy epic walks, from a two-hour traipse around the mirror-like Dove Lake to a daylong hike to the summit of Cradle Mountain. It is also the starting point for the Overland Track, a six-day, 40-mile alpine walk to Lake St Clair.

How to get there

Most visitors use Cradle Mountain or Strahan as a base. Fly to Launceston and drive two and a half hours to Cradle Mountain or three and a half hours to Strahan. Alternatively, fly to Devonport or take the Spirit of Tasmania ferry from Melbourne, which is about one hour closer to each destination.

How to visit

While much of the region remains inaccessible, pockets offer excellent opportunities to disconnect from the outside world and reconnect with nature. Cradle Mountain has a number of accommodation options, as well as companies that specialize in walking tours. The seaside village of Strahan has a dark convict history, as well as wild beaches and dense forests on its door step. Its big drawcard is the opportunity to cruise the Gordon River. One company, Par Avion, offers full-day or multiday adventures to western wilderness and the remote southwest coast.