Families are leading a new wave for Black travelers

For many parents, showing their kids the world is about both the past and the future.

ASK ANY PARENT and they’ll confirm: Taking your kids traveling is an act of bravery.

With favorite snacks and a small mountain of wipes at the ready, parents pack up strollers, ignore the chorus of “Are we there yet?” and set out to show their kids the world. They do it for the same reasons they demand kids eat their vegetables or finish their homework—they believe it’s good for them.

(Here’s how families can make the most out of spring break this year.)

That doesn’t change when you’re a Black family, but there are a few more considerations.

Will we be stared at or accosted in places where few people look like us? Will other people see innocence in our children or treat them according to stereotypes that fill television and movie screens? Will our child’s behavior be viewed as “just a kid being a kid” or intentionally problematic? Will our family feel safe?

In spite of those fears—and sometimes because of them—they travel anyway.

“We’re just like any other traveling family out there, even though sometimes the experience on the ground might be a little bit more challenging for us because of the color of our skin,” says Metanoya Webb, who lives in New York but travels extensively with her son, Journey, age 4.

“No matter how early the introduction, I just knew how valuable it would be for him as a Black male coming up in America to have the gift of travel,” she says.

The Black Lives Matter movement and recent storming of Capitol Hill have shone a light on the racial tensions that remain in America, and for Black families traveling with young children, it adds another consideration to travel decision-making.

A recent study by marketing agency MMGY Global found that concern about safety is an overwhelming (more than 70 percent) concern for Black travelers.

“We avoid most small towns unless we’ve done extensive research on the population there (how many are people of color, what does their police department look like, any negative stories in the news, etc.),” says Montoya Hudson, the chief writer at The Spring Break Family, via email. “If we’re unsure, we don’t go.”

(Life after the ‘Green Book’: What is the future for Black travelers in America?)

But the number of Black family travelers is growing, particularly young families. According to MMGY Global, 12 percent of Black travel parties are comprised of young families, which is greater than the incidence of young families among all U.S. resident travelers.

The reasons why Black families travel, despite the risks, is as much about the past as it is about the future.

Getting a fuller sense of history

“Our history, our culture, and our impact are downplayed,” says Hudson. “If I allowed my children to learn only what is taught in school, then they would think we began with slavery. Traveling fixes that.”

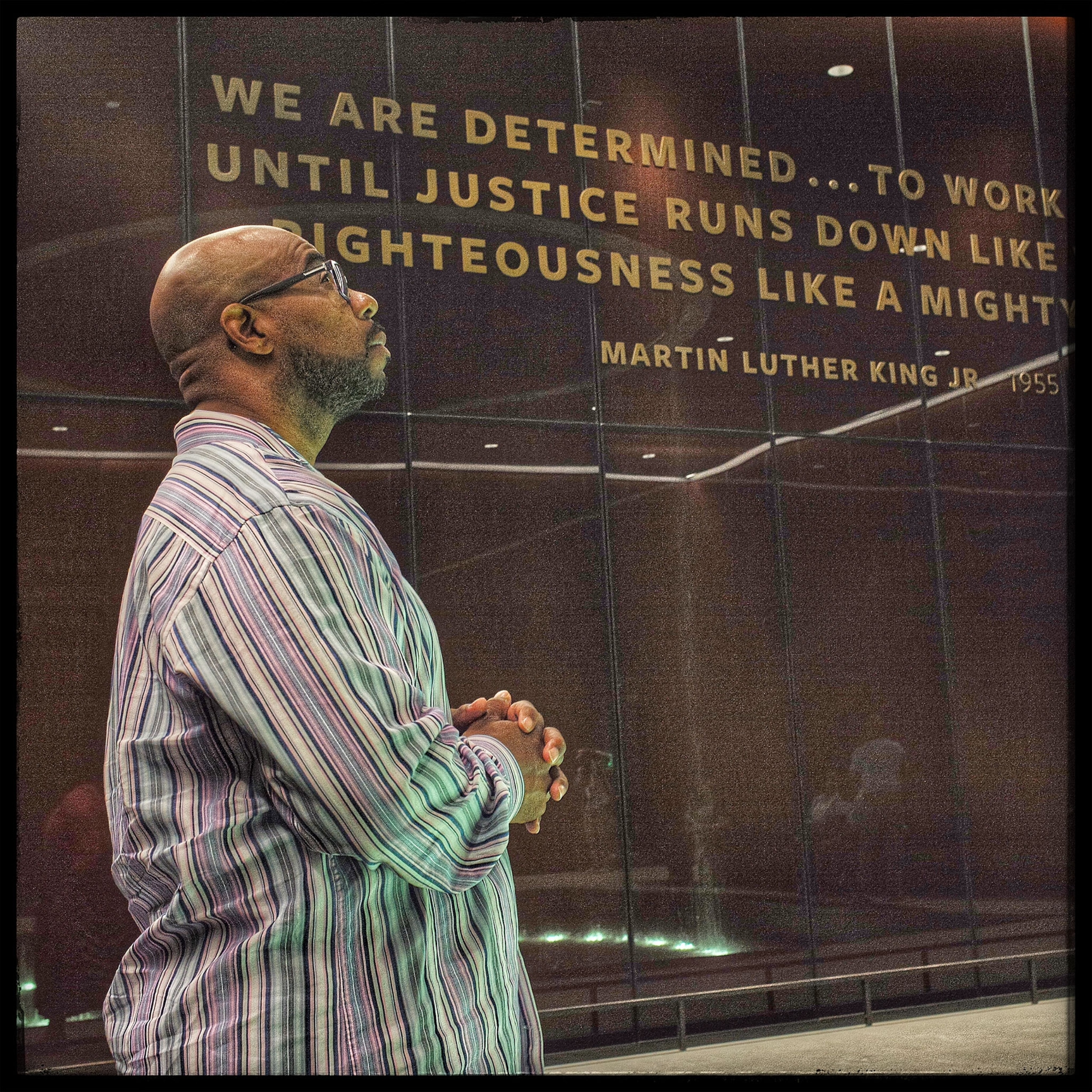

For Hudson, taking her daughters to Memphis, Tennessee, and showing them the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated, was an impactful way of helping them understand the Civil Rights movement.

(Take a road trip along Alabama’s Civil Rights Trail.)

“Travel allows for some of the more positive lessons around Black history that are often left out of the schoolbooks,” says Hudson. “Even with some of the brutal experiences in our history, they can see that we’ve not only endured, but flourished. That’s important.”

Tiffany Miller, who—along with her husband and three kids—travels as The NonRev Family, says they have already visited the National Museum of African American Culture and History in Washington, D.C., three times and would happily return. Places like the National Museum of African American Music, which debuted in Nashville last year, and the forthcoming International African American Museum, in Charleston, South Carolina, are bound to have a similar impact when families begin to travel again.

Black family travelers also laud sites and museums that offer a fuller version of events than textbooks provide. The Whitney Plantation, in Louisiana, tells the history of slavery in America from the perspective of the enslaved people. The Legacy Museum, in Montgomery, Alabama, explains the economic forces that took Black people from slavery to prison. The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument and National Historical Park explores the iconic abolitionist’s legacy and experience growing up on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

“Many Black children don’t live in an area with multicultural, high-performing schools, or with access to diverse cuisine or experiences outside of their normal day-to-day,” Miller says, “so it’s even more important for our Black children to travel.”

Finding community

Stephanie Claytor, a lifelong traveler and the author of Blacktrekking: My Journey Living in Latin America, says that even though her son, Kyler, is only 10 months old, she is already thinking about the places she wants to take him.

“It is very important for me to show and introduce my child to Black people from around the world, as well as expose him to their history and culture,” Claytor says. “This exposure will teach him that he can be anything he wants to be and live anywhere in the world. He is not confined to Tampa Bay, Florida, where he was born. The world is his.”

For her part, Metanoya Webb says that visiting Cuba with her son, and seeing a country filled with people who had skin and hair similar to his own, was affirming. “There was some sort of familiarity that made him comfortable,” Webb says.

“As Black children, especially ones growing up in the South, things can sometimes feel limiting,” says Hudson, “but allowing them to see other areas where race isn’t the same social construct that it is here, or where Black communities are thriving, really broadens their horizons.”

Finding Black community legacy in places where it isn’t always expected is also empowering. In Ontario, Canada, families can visit Chatham-Kent, the home of Josiah Henson, whose story of escaping slavery inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Henson was also one of the masterminds behind the Dawn Settlement, a successful Free Black community. In Nova Scotia, families can learn about the early 19th-century Africville at a museum located on the site of the government-bulldozed, all-Black neighborhood. (A formal apology was issued in 2010.)

In Indianapolis, families can explore the legacy of one of the country’s richest self-made millionaires, Madam C.J. Walker, starting with a new mural celebrating her at the Indianapolis airport.

(Here is why diversity in travel matters.)

Seeing yourself in the world can provide new opportunities for self-confidence and pride. Imani Bashir says global travels with her husband and their son Nasir, 3, have allowed them to show him the intellect and talent of people “just like him.”

“The pyramids of Giza are a must for Black children,” says Bashir. “They need to see that we built such amazing civilizations even that long ago.”

Creating new narratives

Sometimes travel, domestic or international, is less about the sites you see and more about showing your kids that they can be there too.

Casey Palmer lives with his wife, Sarah, and their children, Isaiah, 7, and Xavier, 5, in Toronto, Canada. The mixed-race family loves the outdoors. Recent trips have included Arrowhead Provincial Park, north of the city, and Pinery Provincial Park on Lake Huron.

Bumping into another Black family in the wild has been rare, says Palmer, who is working on a book about Black fatherhood slated for release in 2022. And that’s one of the reasons he continues to get out there with his sons—to show them Black people camp, too.

(Learn about how national parks are working to fight racism.)

“The world is a big place, and I don't want myself or my children to feel boxed in by any restrictions that come from their upbringing or something someone tells them,” says Palmer, who adds he hopes to be able to take his kids to climb Mount Kilimanjaro when they’re older.

“It’s nice to see other Black people traveling, or in places we go, but that’s not the center of our focus,” Bashir says. “I want my son to see the reality of the world and that reality includes people of an assortment of demographics.”

And sometimes it’s a relief to stop thinking about race, and instead just focus on spending time and having fun together, since, as Miller says, “the current state of events has reminded us that nothing is promised, not even tomorrow.”

Heather Greenwood Davis is a Toronto-based travel writer and National Geographic contributing editor. Follow her on Instagram.