The time when flight attendants said: ‘Go fly yourself!’

Groped, pinched, and talked down to, flight attendants learned to fight for their rights. They still keep passengers safer in the skies.

You’ve probably heard about the recent Frontier Airlines flight, in which a drunk, out-of-control airline passenger was duct-taped to his seat. After he groped two female flight attendants and punched their male colleague the crew took action, restraining him for the rest of the journey.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, flight attendant abuse has soared. In 2021, the Federal Aviation Administration recorded 5,981 unruly passenger incidents. Anger about masking rules and the stress of pandemic travel have fueled physical and verbal attacks against workers in the cabin.

Such ire in the skies isn’t new: 50 years ago passengers were regularly belittling, disobeying, and pawing flight attendants—often with the airlines’ tacit approval. A group of courageous “stewardesses” found creative ways to fight back, sparking a tradition of flight attendant activism that continues today.

While researching my new book, The Great Stewardess Rebellion, I learned a lot about the flight attendant industry’s evolution—and revolution. Their story surprised me; their fierceness and feminism inspired me.

‘Sky bunnies’ in airline marketing

In the 1970s, airlines in the United States came up with an ingenious marketing strategy. They didn’t sell tickets based on their safety records, or their destinations. They sold tickets based on their stewardesses.

First, they dressed them in skimpy uniforms. Southwest put stewardesses in orange hot pants and go-go boots. American experimented with a Western look of tartan miniskirts and Daniel Boone-style raccoon hats. TWA designed dresses made out of paper.

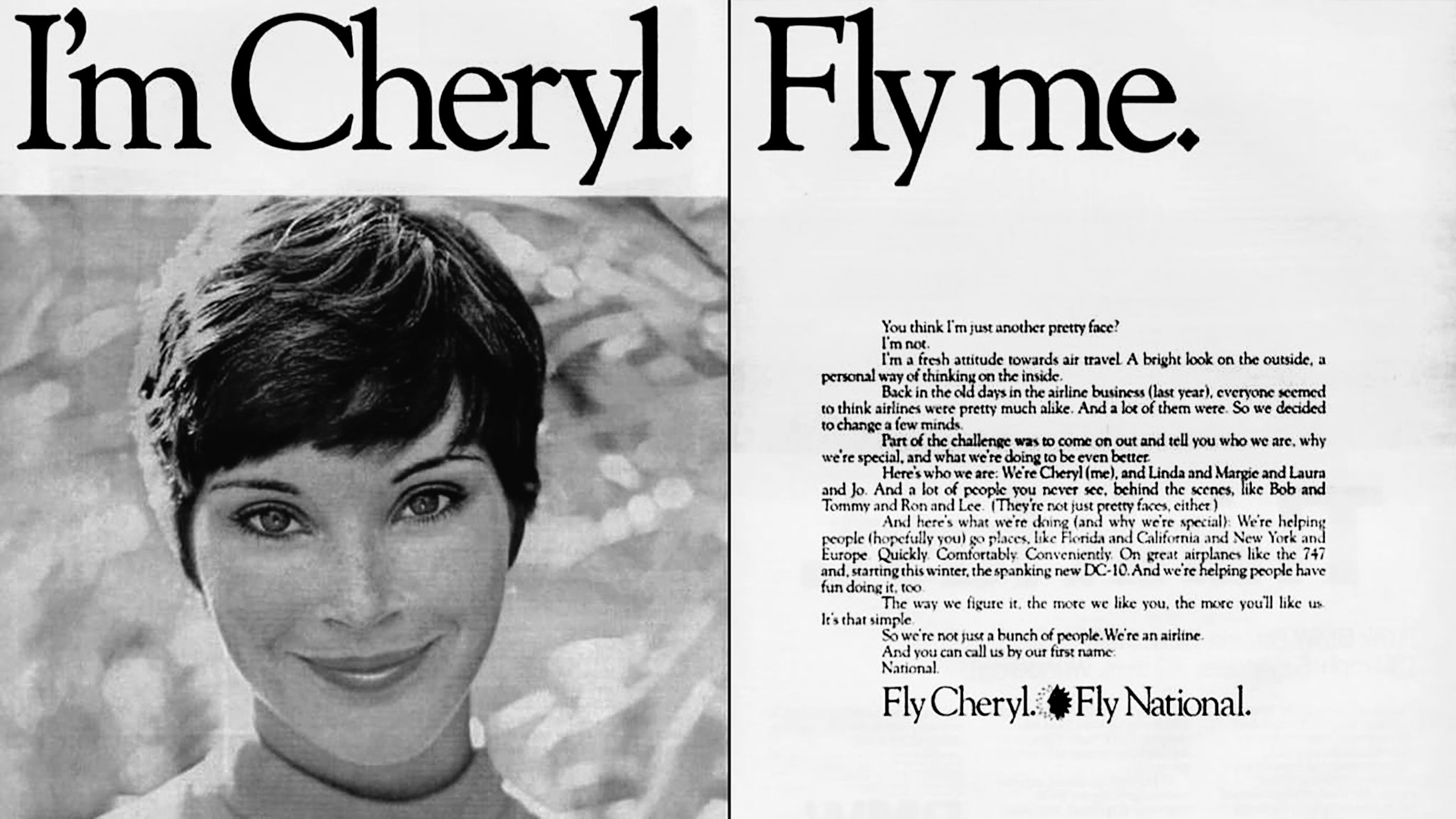

Then the airlines ran print and television ads with the women front and center. National Airlines had huge success with their “Fly Me” campaign, starring real flight attendants who’d declare “I’m Linda. Fly Me.” Continental went with “We Really Move Our Tail For You.”

Braniff was ahead of the curve, launching “The Air Strip” campaign in 1965. This meant its female flight attendants boarded the plane in sherbet-colored outfits, then removed layers throughout the journey. Just before take off, they’d unzip their coats to reveal blouse and skirt outfits. After serving dinner, the stewardesses would unwrap their skirts and pull off their blouses to expose slinky bloomer-turtleneck combos.

Many passengers loved the “sky bunny” approach. But the more salacious the ads got (and the skimpier the uniforms), the harder it was for the flight attendants to get passengers to take them seriously. They were groped, pinched, and talked down to. In 1967, a stewardess was conducting an emergency evacuation when a male passenger picked her up and carried her off the plane, declaring, “You shouldn’t be here.”

(These vintage photos show the timeless appeal of travel.)

Sometimes the airlines themselves offered up their stewardesses as sex objects; in the mid-1970s, the executives at Continental decreed that their female flight attendants had to kiss every departing male passenger on the cheek.

Booze stoked bad behavior. Many of the Boeing 747s introduced in 1970 held second-floor cocktail lounges. Passengers could climb a spiral staircase to reach a full bar. They’d have too many drinks and drop their lit cigarettes in the airplane aisle or tumble down the stairs. Flight attendants protested, and alcohol limits soon came back into force.

Flight attendants strike back

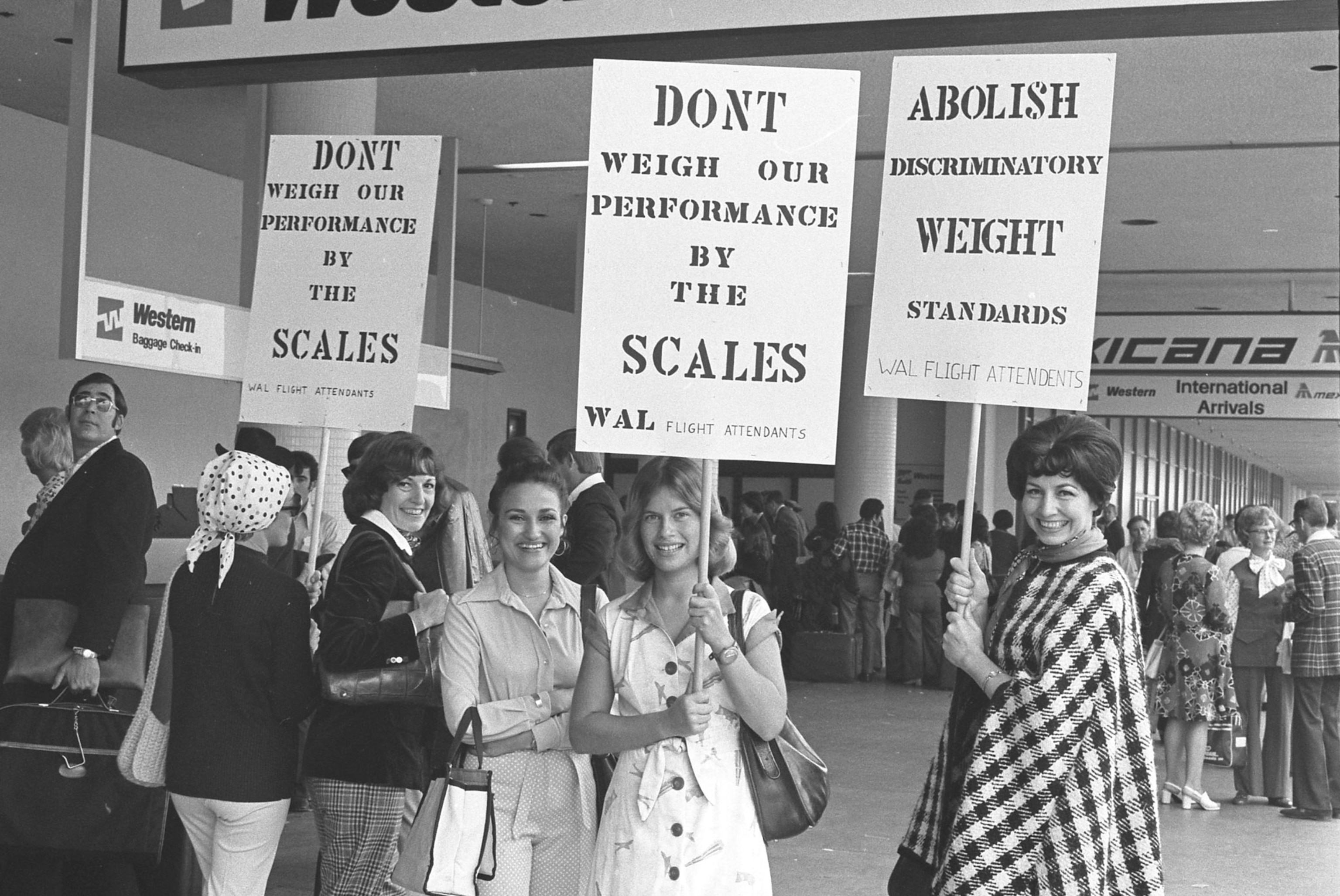

In 1972, furious with passenger behavior—and the airlines, with their risqué ads and tarty uniforms—a group of women calling themselves Stewardesses for Women’s Rights decided to fight back. They took to the streets, marching outside the New York City advertising agencies that had created the sexist campaigns.

“The airlines gear you into being a sex object,” said one of the group’s founders, Sandra Jarrell, speaking to the Los Angeles Times in 1972. “They brainwash you into accepting it and expecting it. You lose your self-respect ... People don’t consider you a professional, so you don’t think of yourself as one.”

(Explore how women-only tours are changing how we travel.)

The women particularly hated the double entendre of “Fly Me,” so they made picket signs reading “Go Fly Yourself!” They produced and aired counter-commercials demonstrating how treating stewardesses as sex objects put customers in danger.

In one, an actor in a stewardess uniform delivered their message. “I am a highly trained professional with a serious job to do,” she said, looking directly at the camera. “Should an emergency situation arise, I urgently need the respect, confidence, and cooperation of all my passengers. Fantasies are fine—in their place—let’s be honest, the ‘sexpot stewardess’ image is unsafe at any altitude! Think about it.”

These women campaigned for the legal right to be treated as safety professionals, spending years pushing the U.S. government to require licensing for flight attendants. From 1972 to 1976, Stewardesses for Women’s Rights organized boycotts of companies (e.g. Hanes stockings, Closeup toothpaste) which ran commercials portraying stewardesses as dimwitted pin-ups. Firestone, which had an ad showing a stewardess selecting snow tires in a no-nonsense way, received letters of approval.

And they made sure the press knew about their efforts. Stewardesses fighting for women’s rights? That was a hook that made headlines.

Still on the front lines

Although the era of hot-pants and “Fly Me” is past, the myth of the promiscuous cocktail waitress in the sky remains. Some of it is plain old sexism. “Stewards” didn’t start working domestic U.S. flights until the early 1970s, and even now, men make up only 20 percent of working flight attendants.

The flight attendants’ decades-long fight for respect produced results, though. Their activism resulted in the first federal legislation regulating smoking in the workplace in 1989. In 2003—after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 forced a reevaluation of air travel security—they finally persuaded Congress to license them as safety professionals.

Today they continue to hold the line against abusive passengers. During the pandemic, flight attendants have called on their unions to stand up for them after months of little to no help from the airlines. The Association of Flight Attendants, the country’s largest such union, asked the U.S. Congress to create a list of banned passengers for all airlines to share.

These activist attendants are telling the media about how the public treats them, and they’re taking self-defense classes. Their 1970s forbearers learned how to dodge wandering hands; U.S. Air Marshals are schooling 2020s flight attendants in how to punch, scratch, or eye-gouge attackers.

(How flight attendants adapted to pandemic-era travel.)

As before, the liquor cart isn’t helping. “The incidents of violence on planes is out of control and alcohol is often a contributor,” Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants, told the Washington Post. Her group successfully lobbied for the alcohol sales ban on domestic flights, which has been in place for much of the past two years. (Booze quickly resurged in first class, and is only now starting to come back in economy.)

Although today’s flight attendant abuse is disturbing, few people still think of the workers as disposable Barbies, meant to indulge passengers’ whims. Contemporary flight attendants are following in the footsteps of their predecessors, using unions, the press, legislation, and picketing to get things done.

If that doesn’t work, there’s always duct tape.