These Nepalese homestays are transforming Himalayan travel

Nepal is famed for its high-altitude trekking routes, drawing adventurers to scale the soaring peaks of Everest and Annapurna — but for those seeking a deeper connection to local life, homestays invite visitors into the family fold.

A teenage boy strides across the courtyard, casually scooping a chicken from the ground and tucking it under his arm like a plumed designer clutch bag. Shortly after, the same bird makes a surprise reappearance on my plate — charred feathers and all. It’s part of an elaborate feast prepared by Kamala Rai, my host for the next few days in Sipting, a village in the mist-shrouded hills of eastern Nepal’s Dhankuta region.

Kamala, her hair wrapped in a vibrant flash of fuchsia-coloured silk, deftly tends to steaming pots and pans as we chat in her kitchen, lit by stubs of candles following a temporary electricity cut. She’s quick to explain that roasting the household chicken over an open flame isn’t a daily affair. No, this one was sacrificed in my honour — an offering to mark my arrival at her family’s doorstep.

Just beyond the kitchen hut’s mud-baked walls, the pounding of drums rises, a growing symphony from a group of local musicians limbering up to welcome me in an all-singing-all-dancing ceremony that will roll on late into the evening. It’s the kind of heartfelt reception sadly lacking at your run-of-the-mill hotel. And it’s exactly these moments that have drawn me to Nepal — a landlocked country cradled between the sprawling mosaic of India and the highlands of Tibet.

Seeking true immersion into Nepalese culture, I’m on an eight-day trip organised by the Community Homestay Network, a social enterprise with around 350 members dotted across the country. The recently launched Road Less Taken tour promised glimpses of authentic local life, following a route from Dhankuta in the east, stopping for a night in the city of Janakpur, then pausing for a couple of days in the ancient town of Panauti before looping back to the capital of Kathmandu. The expedition would take me into communities barely touched by tourism, with the aim of putting money into the pockets of rural women and their families along the way, with 80% of the overnight fee going directly to the host.

My journey begins with a two-night stay at Kamala’s house, offering a revealing window into local village life. She tells me she’s from the Aathpahariya community, a tight-knit Indigenous group that’s carved out a life close to the land in this remote part of Nepal. For centuries, they’ve held on to their distinct language and traditions, as well as their eye-catching dress, with bright geometric textiles draped over women’s shoulders, shimmering coin necklaces strung around necks and joyful pom-poms woven into the hair of girls. It’s a secluded culture deeply rooted in the earth, but, in recent generations, the allure of big cities has siphoned away its youth, threatening to unravel this delicate way of life. Hope flickers, however — a rising hospitality industry might just offer the younger people a reason to stay put and retain their heritage.

It’s still early days, but Sipting has five homestays — each one connected by family ties. Kamala, a 48-year-old grandmother living with five of her relatives, was initially sceptical about opening the door of her mud, bamboo and stone home to strangers. Space, was never the problem — there’s plenty of room at the inn. Kamala’s sprawling compound is a labyrinth of rooms, painted in bold strokes of sky blue and Pepto Bismol pink, set against a backdrop of orange groves and mountains cloaked in thick jungle.

There’s a laid-back harmony here, with the family and their cattle coexisting cheek by jowl. Children play in the dusty courtyard, their laughter drifting past doe-eyed cows that idle away their days chewing hay in a corrugated iron shed, which is tacked to the side of the main house. But, still, as a member of a marginalised community, far from the tourist trail, Kamala had her doubts. “I wondered, why would anyone be interested in our life?” she asks with a quizzical smile, her eyes crinkling as if the question feels a little surreal.

With only a handful of signatures in her guest book so far, Kamala admits she’s still finding her feet — learning the hospitality ropes and overcoming her natural shyness. When words fail, she leans into the universal language of food. “We’ve had a few international guests, and I love cooking our traditional dishes for them. I’ve also picked up a few new recipes along the way, as part of my host training,” she says cheerfully, ladling a second huge spoonful of her fiery chicken curry onto my plate, followed by another.

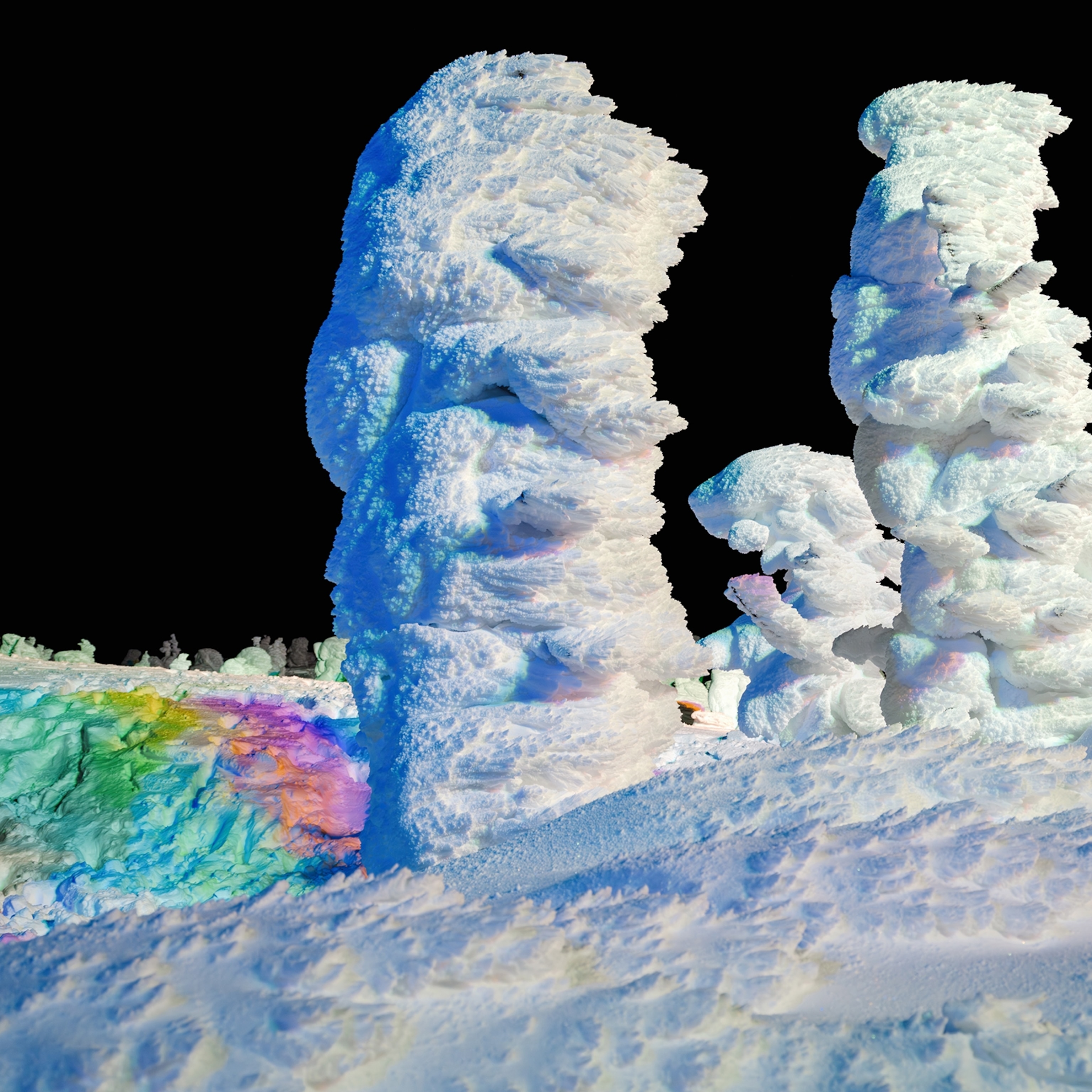

(Why Himalayan hiking trails in Nepal are a photographer's dream)

Close to home

The following day, I meet Nabin Rai at the entrance to the nearby Chuliban forest. Like Kamala, Nabin is from the Aathpahariya community, and he’s also quietly optimistic about the potential of local tourism. Today, he’s taking me on a guided walk, organised by the Community Homestay Network, through the dense woodland that surrounds Khambela — the village where he was born and raised.

It’s only the second time Nabin’s played the role of guide. I can see the tension in his shoulders as he pushes through both his nerves and the language barrier, the light dusting of a moustache on his upper lip making him appear younger than his 22 years. As we trek deeper into the forest, tangled vines alive with the chatter of swinging monkeys, Nabin tells me he’s the last of his schoolmates to remain in Khambela. The rest have long since flown the nest for Nepalese cities or for construction jobs in the Middle East.

But Nabin, for now, has his sights set closer to home. “I’m excited that foreign guests are starting to visit us,” he enthuses, his gaze sweeping over the forest, “because I dream of being a tour guide full-time. I’m living with my dad right now, but maybe one day, I’ll have my own homestay, too.”

We stop at a lookout tower, tucked deep within the thicket. After a breathless climb up five flights of stairs, we’re rewarded with sweeping views of the valley. The Tamor River winds below us, a glistening ribbon threading through fields and clusters of thatched roofs, so far below that it feels like we’re peering down on it from an aeroplane window.

Nabin points out ancient trees wrapped in dry stone walls, explaining that his people worship nature — treating the landscape around us like a living, breathing temple. As we make our way into his village, we stop at the home of a local family, where the women of the household rustle up fermented beans and spinach served in bowls made from leaves, stitched together with bamboo splinters. Spontaneously, we join a group of villagers gathered around a carrom board — a tabletop game originally from India in which players flick discs onto one another, trying to knock them into the corners. It’s a welcome shift from normal life: no one’s staring at their smartphone or in a rush. Instead, the afternoon pulses with the gentle rhythm of pastoral life.

Before our time together comes to an end, I ask Nabin what keeps him tethered to these foothills, despite the obvious isolation for someone of his age. “Before you can change the world,” he reflects with a smile, “you have to change what’s around you first.”

New-wave thalis

The green peaks of Dhankuta fade in the rear-view mirror as my driver and I make the six-hour journey to Janakpur, a city near the Indian border in southeastern Nepal. Along the way, life in all its chaotic, colourful glory plays out on the roadside. Elaborately decorated trucks overtake us, Bollywood songs blasting from them as they honk their horns. Women draped in crimson saris, their fabric shimmering with sequins, ride sidesaddle on the backs of chugging mopeds, cradling kohl-eyed toddlers in their arms. Farmers carry bamboo baskets taller than their own bodies, somehow making the load seem as light as a feather. And then there are the cows — unhurried, strolling right down the middle of the road, their every step a reminder of who has the right of way around here.

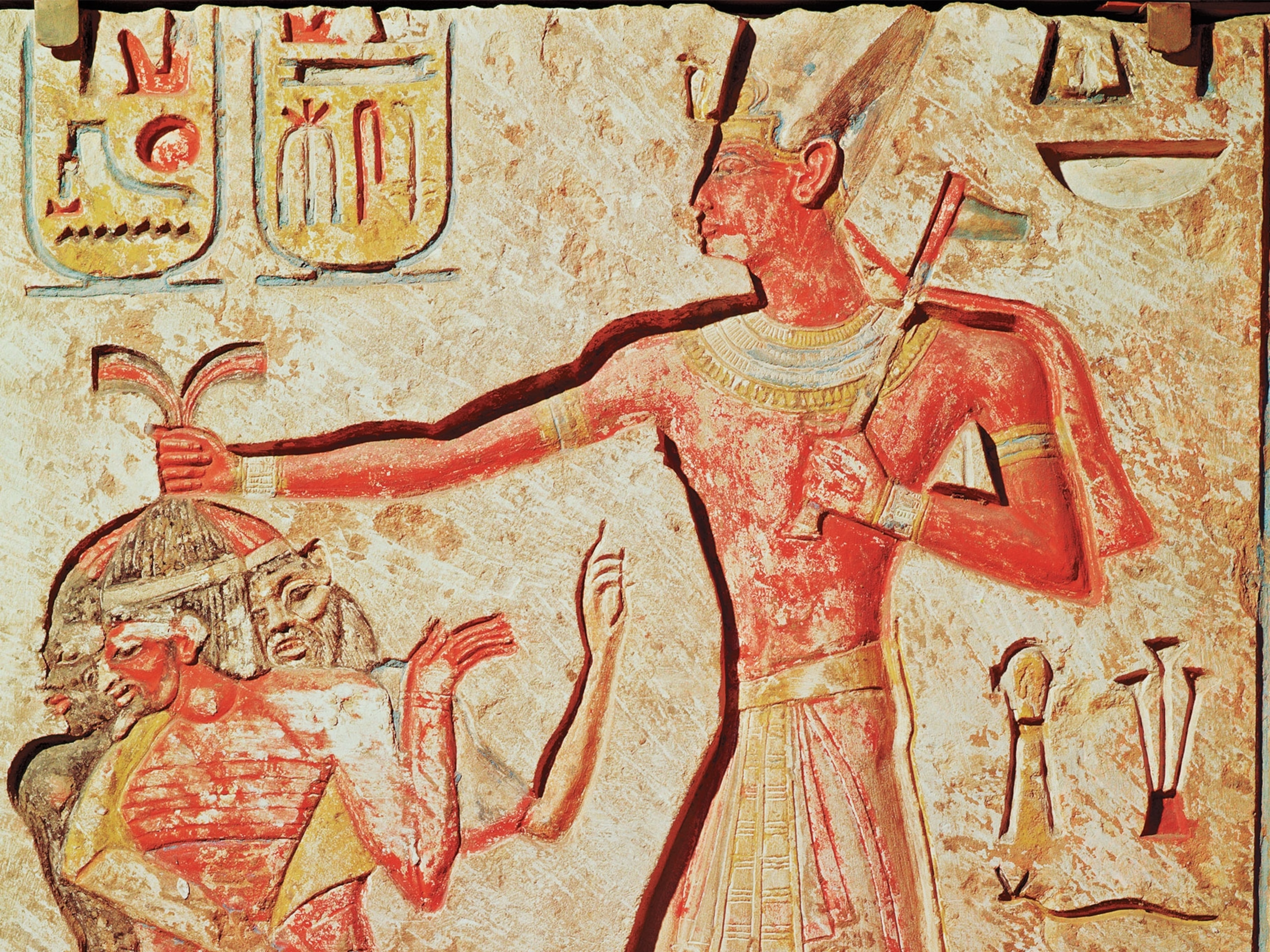

When we finally pull into Janakpur, I make a beeline for the city’s crown jewel: the Janaki Mandir, a sprawling temple built in 1874 to honour the Hindu goddess Sita, believed to have been born here. So vast is the symmetrical structure that it requires a full head turn to admire its entire gleaming white facade, trimmed with intricate carvings and daubed with splashes of colour. Pilgrims stream through its arched doorways, their bare feet padding across the marble floor as they offer up prayers and light incense, garlands of flowers at their chests. The air is thick with devotion and murmured chants, creating a sanctuary of calm in an otherwise frantic blur of a city.

While the temple may command spiritual reverence, I’m now hungry for the culinary delights of Janakpur. The city’s food scene has gained international fame, thanks in no small part to local legend Santosh Shah. A remarkable success story, Santosh rose from an impoverished childhood selling plastic bags on the streets to heading up kitchens in some of the UK’s most celebrated restaurants, including Dishoom and the Cinnamon Club. After winning the TV show MasterChef: The Professionals Rematch in 2021, Santosh returned to Nepal to fulfil a dream that had simmered for years — opening his own restaurant, the Mithila Thali.

“This is the taste of my childhood,” he tells me as a hand-painted tray, jostling with small silver thali dishes, lands on the table. Elephant foot yam, flatbreads, tangy pickles and fragrant spiced lentils — this is the everyday food of Nepal, but subtly refined. Around us, the dining room hums with a mix of local patrons: market vendors, noisy extended families, groups of students sipping lassi and a local dignitary, flanked by a pair of hulking minders. Despite the diversity of faces and backgrounds, there’s a sense of shared space here, with everyone enjoying their food under the slow spin of the wooden ceiling fans.

It’s exactly the vibe Santosh envisioned, he tells me, pointing out that his gamble to keep prices accessible has paid off — Mithila Thali now draws in over 500 customers a day. “I kept the concept simple — it’s about creating food that tastes authentic to this region,” he says. It’s clear from the buzz in the room that Janakpur has embraced his dream.

As night falls, I hop into a tuk-tuk, its kitschy lights twinkling like a Christmas tree, and head back to my hotel in central Janakpur. With the itinerary alternating between community homestays and traditional hotels, tonight, I’m reminded of the small luxuries— high-speed wi-fi, a Western-style toilet and the chilled breath of an air-conditioning unit. But as I settle into bed, my heart already longs for the exuberance of a spare room in the mountains — the wake-up call of a crowing cockerel, the Barbie-pink mosquito net hung above the bed and the colourful walls adorned with framed family portraits of mysterious relatives that I’m yet to encounter.

Matriarchs and momos

At my next stop in Panauti, I find myself at the birthplace of Community Homestays. Tucked into the hills of the Kathmandu Valley, just 20 miles south east of the capital, this historic town offers more than just winding alleys and centuries-old temples. It was here, in 2012, that the women-led homestay movement first took hold. Mina Koirala, my host for the next two nights, was one of the earliest trailblazers. After her husband passed away, the former housewife transformed two of her bedrooms into accommodation for guests, creating a lifeline for her and her four children.

I slip into a chair in Mina’s cerise-painted kitchen, the shrill whistle of a rice cooker piercing the air and signalling that dinner’s almost ready. Her grown daughters and a grandchild gather around the table, a chorus of voices rising and falling in Nepali, with the occasional English word slipping through. Vegetables are chopped, pots are stirred and a plate of momo dumplings — which we made earlier together — takes centre stage. The family moves with practised ease, so comfortable hosting me that I feel almost invisible. It’s less like being a lodger and more like being a fly on the wall in their dynamic domestic sphere.

“I haven’t left my country,” Mina admits, her bangles jingle-jangling as she hands around another plate of crimped dumplings. “But with all the guests who have come through my door, I feel like I’ve travelled the whole world.” She adds with a quiet pride that she’s been able to put her children through school and university with the money she’s earned from the venture.

What strikes me most about homestay culture is the central role women play in it. In a country where access to education, employment and economic independence has often been a struggle for females, Panauti offers a different story. In this town, with its 17 homestays run by women, Mina and others like her have transformed their homes into lively hubs of financial independence and cultural exchange. These Nepalese women haven’t just opened their doors — they’ve reshaped their entire futures, one guest at a time.

On my final morning in Panauti, I wake to the sun spilling through the floral curtains pinned over my bedroom window. Downstairs, I join Mina’s daughter, Neelam Gupta, for a walk through town. We stroll past swaying rice fields, then along narrow cobblestone streets towards the Indreshwar Mahadev Temple, one of the tallest pagoda-style temples in Nepal, which dates back to the 12th century. As we walk, Neelam offers a candid reflection on the experience of hosting visitors.

“If you’re after luxury, you should probably just stay in a fancy hotel — but the rooms and food, they’re the same anywhere in the world at these places,” she says, shrugging. “Homestays are different. They offer something more authentic.” We stop by the embankment where the mighty Rosi and Punyamati rivers converge; a clinking metal bridge stretches across the water, festooned with resident’s washing drying in the sun. “If you stay in my family’s home, you aren’t just passing though. Our motto is Atithi Devo Bhava — the guest is God.”

Later that afternoon, we drop by a neighbour’s house for a bite to eat. Inside, a group of teenagers is sprawled across the lounge carpet, deep into a card game. A disco ball whirls overhead, throwing glimmers of multicoloured light across the room, which is furnished with a red satin sofa, a cabinet brimming with sports trophies and a Real Madrid football scarf pinned to the wall. Our arrival goes completely unnoticed, the group’s lively banter flowing on uninterrupted. In that moment, a wave of deja vu washes over me— I’m more than 4,500 miles from home, in a different country and culture, yet this scene could be unfolding in my own living room. It’s as if an invisible bridge has connected our families’ lives, revealing that, in many ways, they aren’t so distant after all.

A few days later, back in the frenzy of Kathmandu, I find myself among throngs of hikers kitted out in windbreakers, their boots dusted with dried mud, trekking poles jutting from backpacks. They’re heading back from the mountains, no doubt having chased the same summit dreams that draw so many to Nepal. Unlike them, I can’t claim to have conquered any Himalayan peaks. What I did find, however, was something every bit as thrilling; a fleeting intimacy with families that weren’t my own, yet somehow made me feel part of their world.

(Photo story: the Nepalese honey hunters facing some of the largest bees in the world)

How to do it

There are no direct flights from the UK to Nepal. Airlines including KLM, Emirates and Turkish Airlines fly from Heathrow to Kathmandu, with stopovers in their hubs.

Average flight time: 14h40m.

Tourist buses connect popular routes such as Kathmandu to Pokhara and Sauraha. The train network is very limited, with just one passenger line running along the southern part of Nepal near the border with India. Hire cars or short-haul flights are popular for longer distances, while tuk-tuks and taxis operate in the cities.

When to go:

Nepal’s high seasons are September to November and March to May, with temperatures between 20-30C. Winds can be biting in winter, December to February, with an average temperature of 8C in January — although the trekking trails are at their quietest then. Spring is a pleasant time to visit, with clear skies and rhododendrons in bloom in eastern Nepal. June to August is monsoon season and flash floods can disrupt travel by air or road.

Who can help:

Asia specialist Experience Travel Group offers an eight-day trip, including activities such as a sound bath, painting workshop, cooking class and village visits. Accommodation is in a mixture of community homestays and hotels, with all meals, international flights, transportation within Nepal and a guide included; from £2,800.

More info:

ntb.gov.np

This story was created with the support of Experience Travel Group and the Community Homestay Network.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).