Take a virtual tour of South Carolina’s only civil rights museum

Photographer Cecil Williams’ museum is dedicated to “the South Carolina events that changed America.”

Nestled in a residential section of Orangeburg, South Carolina, there’s a 3,500-square-foot structure that’s so minimalist, it looks at first glance like an elegant series of conjoined blocks.

It is actually a museum designed, built, and outfitted by photographer Cecil Williams. And while there are several sites in South Carolina on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, this place is the only one commemorating the entirety of the civil rights movement in the state.

Among the hundreds of thousands of images that Williams has captured in his lifetime, the most popular is of a young African-American boy, dressed in a white shirt and suspenders, looking upward with bright eyes as he holds his mother’s hand at a rally in 1963.

Only a few feet away from where Williams has displayed that picture, another of his frames stops visitors in their tracks just as suddenly: a pair of cupped Black hands in closeup, holding half a dozen bullet cartridges. The shell casings were left behind when highway patrolmen fired their guns into a crowd of student demonstrators at South Carolina State University in 1968, killing three and wounding 28 in what became known as the Orangeburg Massacre.

Williams has spent nearly seven decades chronicling the hopes and agonies of struggles for civil rights in photos like these. Now he has placed more than 300 of his artifacts in the Cecil Williams Civil Rights Museum, which he plans to open to the public when the coronavirus pandemic recedes.

It just clicked

Williams, now 83, was nine years old when he clicked the shutter of his first camera—a $2.50 Kodak Brownie from the Sears catalog. He already loved to draw and found photography allowed him better and quicker artistic expression.

He also discovered he could make money from pictures he took at weddings and gardens. At 11, young Williams set up a darkroom in his family’s house and began developing his own photos in the bathroom sink—or the tub, if he had a large batch to process. He soon moved up to a more sophisticated camera with a flash unit. And he read everything he could get his hands on at a local soda shop, where a friendly saleswoman let him delve into unsold copies of photography magazines. “I would even wear my camera in my classrooms,” he recalls. “I was hooked.”

Williams learned early lessons in discrimination, too. He still remembers his first encounter with racism: At the age of 5, he paid a dollar for a toy car at a five-and-dime store, and a hateful clerk slammed 15 cents of change on the counter between them. Williams couldn’t read books at the county library, which was off-limits to Blacks. He wanted to study architecture at Clemson University, but the school wouldn’t even consider applications from African Americans.

But he felt the times changing. Williams’s mother, Ethel, was a teacher working under Rev. J.A. DeLaine, a principal and minister who organized Black families to demand school buses and protest public-school segregation as early as 1949. Their efforts led to a court case called Briggs v. Elliott, a key forerunner of Brown v. Board of Education. Williams photographed many of the participants. “We were leaving the method of accommodation, which my parents had endured,” he says.

(Related: These powerful portraits tell the stories of Black America.)

Williams began freelancing, shooting local events, and offering his images to local papers willing to do business with an African American. He developed a knack for getting to the right place at the right time–always an important skill for photographers, but especially so in the days of analog equipment and single-use flash bulbs. When Thurgood Marshall visited Charleston, Williams got off one shot of the great attorney stepping off the train and captured a famous image of Marshall as a traveler, with hat, coat, and Samsonite luggage.

Elbowing in

From the beginning, Williams was fearless. He once covered a basketball game, then drove to a Ku Klux Klan meeting. By the time he arrived, only two attendees were left: the grand dragon of the Klan and a state highway patrolman, who looked at each other as Williams approached, camera in hand.

“You want to take a picture of this?” the Klan leader asked.

Williams not only said yes, he suggested the whole group re-erect a smoldering cross lying nearby. “So I took a picture of the two of them standing by that,” Williams says. “Had my parents found out I was there, they would have really done me in.”

When desegregation battles started heating up in Orangeburg, Jet magazine, a sister publication to Ebony, hired Williams as a correspondent even though he was still just a teenager. Jet needed great pictures every week; Williams supplied his editors with film via airmail envelopes and turned his passion into a career.

In January 1960, Williams, then a senior at Claflin University, was in New York visiting relatives and camera stores when he read that Senator John F. Kennedy, who was on the verge of announcing his presidential run, would be appearing in the city. Williams made his way to the Roosevelt Hotel, walked through the lobby, and entered the ballroom—where he was immediately noticed by security guards. Williams didn’t have his press pass, and was about to be thrown out when John and Jacqueline Kennedy entered. The senator, noticing the commotion, said, “No, let him stay.”

(Related: Williams is not the only trailblazing Black photographer. Meet Gordon Parks.)

Kennedy put his arm around Williams and, as they walked, asked him what he was doing there. “I told him I had been a photographer all my life, and he was fascinated by that,” Williams recalls. JFK gave Williams his personal phone number and sat him in the front row of the press section. “Luckily for me,” Williams says, “since I only had a standard twin lens camera and not a telephoto, so I had a close-up view. I just had a field day in there.”

A galvanizing moment

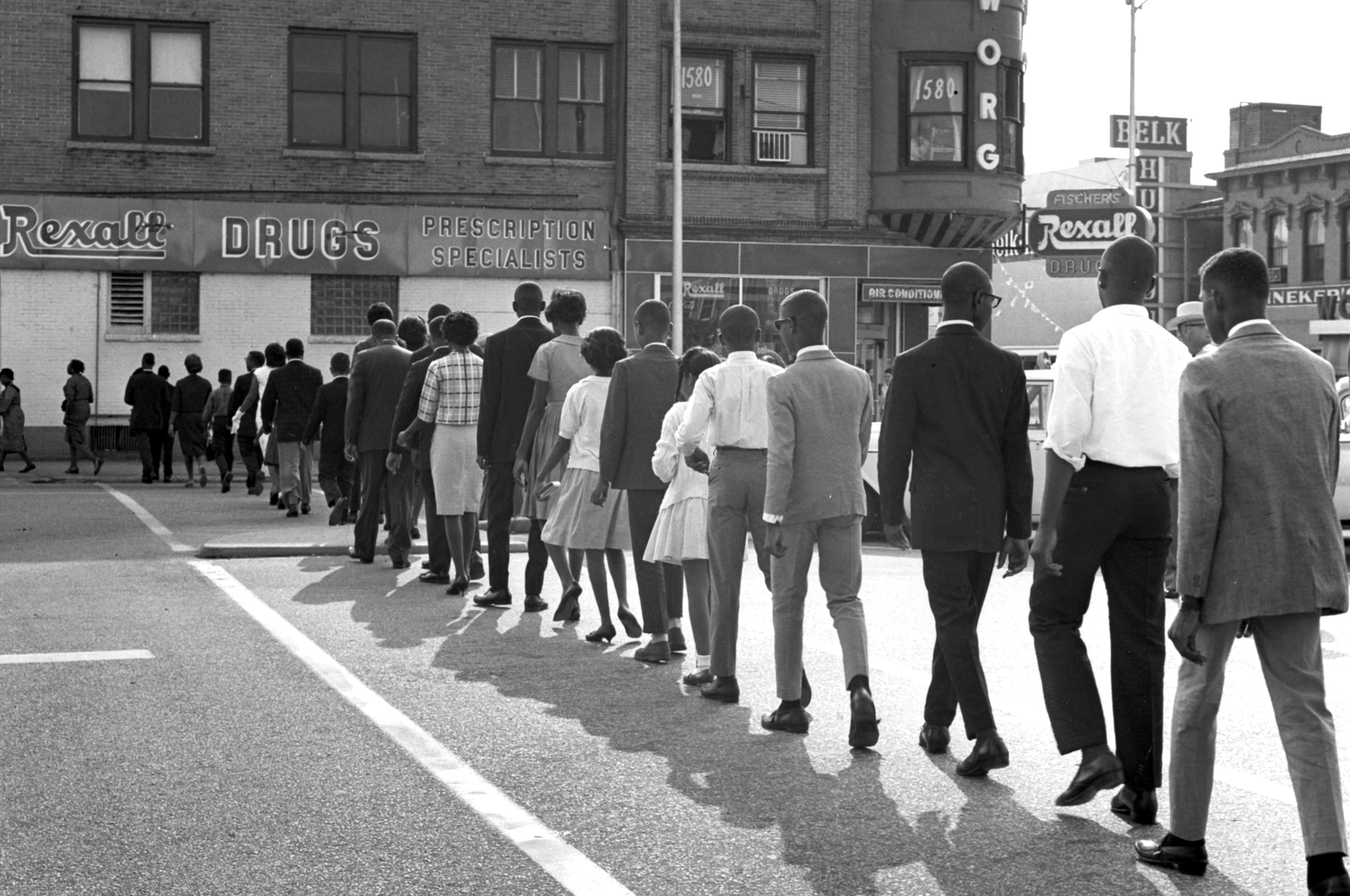

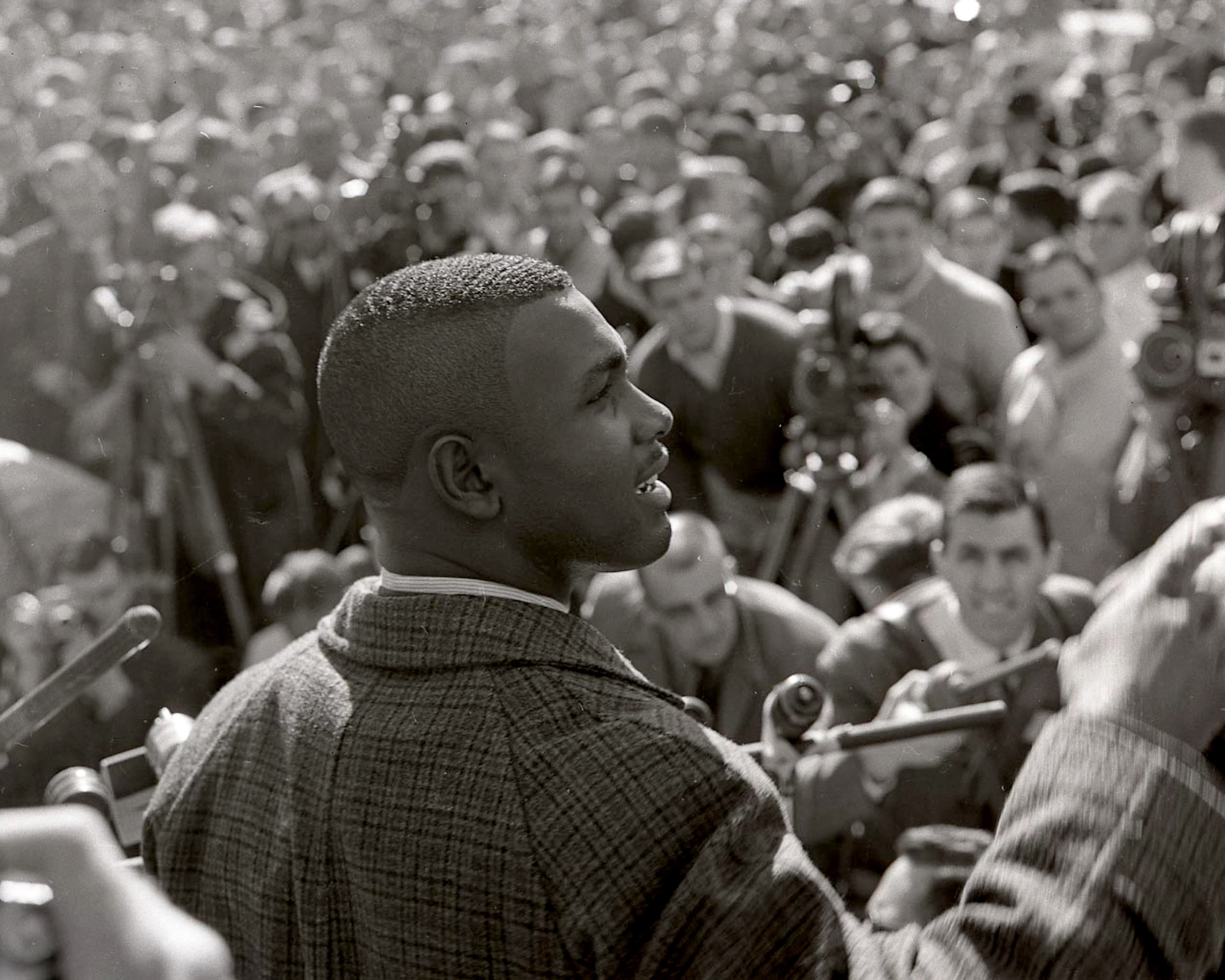

Back home, Williams became a one-man photojournalism bureau. Later in 1960, he took pictures of a sit-in at Orangeburg; police arrested him and threw his Rolleiflex camera in the trunk of a patrol car. And he was on the scene in 1963 when Harvey Gantt became the first Black student to attend Clemson University. “Clemson still calls it ‘integration with dignity,’” Williams says. “That’s because law enforcement cleared it of all the students and faculty. Even the African Americans working the dining hall and maintenance were told not to come to work that day. Harvey Gantt, the gentleman from the New York Amsterdam News and I, we were the only people of color on campus that morning.”

In 1968, Williams was working as the official photographer for South Carolina State University—like Claflin, a historically Black school in Orangeburg—when he covered student protests to integrate the local All-Star bowling alley. On the night of February 8, while Williams happened to be away grabbing a burger, police and National Guard troops confronted about 200 demonstrators on campus. Highway patrolmen blasted carbines and shotguns at the group and hit more than 30 people.

(Related: Why must we protest to enact change?)

Williams couldn’t get back onto the school grounds until the next day. “It was eerily silent, a misty, cold morning,” he remembers. “As I drove along the field, I saw debris all over the place. There was not even crime scene tape on the area—after the authorities stopped shooting the students, they just left. I picked up the shells.”

Williams gave some of the bullet casings to the FBI, which helped link the deadly shots to guns used by law enforcement. But nine patrol officers charged with using excessive force were quickly acquitted anyway. “The students were my friends,” Williams says of the victims. “The three people who were killed, I had taken all of their pictures.”

Williams went on to work for the South Carolina NAACP for more than 20 years, and made two losing bids for the U.S. Senate seat held by famed segregationist Strom Thurmond. But over time, he perceived a disheartening drift in the civil rights movement. “In the mid-1970s and ’80s,” he says, “there was an attitude that, okay, we’ve made these advances, now let’s just quietly assimilate and ride off into the sunset.”

Building a museum

He also noticed that many of the landmark events he photographed didn’t get as much attention—across national headlines, in textbooks, or on monuments—as legal or political battles in other parts of the country. Few Americans ever heard about the Briggs case or understood that sit-ins were taking place in Orangeburg and Rock Hill, South Carolina, at the same time protesters were famously using the same tactic in Greensboro, North Carolina. The Orangeburg Massacre drew a fraction of the attention generated when members of the Ohio National Guard fired on a peace rally at Kent State and killed four white students in 1970. As with Gantt, it seemed local leaders preferred quiet and called it dignity.

“South Carolina has a buried history,” says preservationist Catherine Fleming Bruce, author of The Sustainers: Being, Building and Doing Good through Activism in the Sacred Spaces of Civil Rights, Human Rights and Social Movements. “Our establishment uses the language of peaceful transition, as though civil rights happened but we handled it, even though there have been periods of outrage and protest.”

So Williams started seeking support for a museum dedicated to, as he puts it, “the South Carolina events that changed America.” And after a decade of polite interest but no commitments from state and local public officials, he decided to create it himself.

Although Williams never was able to go to Clemson, he taught himself enough to design three houses. He and his wife, Barbara, a longtime educator, lived in one of them, and this became the Cecil Williams Civil Rights Museum. “I decided this building might be the very best place,” he says. “It represented the inspiration I got for being denied the chance to get my degree in architecture. Overcoming that obstacle is in the design of this house.”

For the past year and a half, Williams himself has cleared space in the museum, tiled its floors, re-furnished its rooms. He has framed, hung, and captioned the photos that line its walls. And he’s built exhibits to house its keynote items, from Marshall’s Samsonite suitcase to bowling pins from the All-Star lanes to a Confederate flag that once flew over the South Carolina state capitol. Until the grand opening, virtual tours are available for $20.

(Related: Here are 13 destinations to learn about African-American history and culture.)

Williams is not quite ready to consider the museum his legacy. He is still working on exhibits. He’s also in a race against time to digitize his images before his old film decays. But he says this with pride about the first and only institution of its kind in South Carolina: “It’s a symbol of what could be achieved.”