Werner Herzog: ‘The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot’

The German filmmaker on the magic of walking, the irrelevance of bucket lists, and his new documentary about Bruce Chatwin.

In 1989 a tattered copy of Newsweek ended up in a tiny village on the edge of the Kalahari Desert and fell into the hands of a homesick English teacher. It contained the obituary of a writer named Bruce Chatwin, who, after years of far-flung travels, had reportedly died at 48 of a rare disease picked up on one of his adventures. The article recounted the legendary story of how Chatwin had quit his job in London by sending his boss a telegram that simply read: “Gone to Patagonia,” which set him onto an illustrious career as a travel writer and novelist.

Several months later, the English teacher was on a long bus ride, when his seatmate, a young French traveler, told him about a German filmmaker named Werner Herzog, who had required his crew to haul a steamship up a hill in the Amazon for a scene in a film called Fitzcarraldo. Herzog had then starred in a documentary about making that film.

That English teacher was me, and such was my introduction to two of the 20th century’s most original storytellers. Ever since, Chatwin’s books and Herzog’s films have been absorbed into the deep folds of my imagination, spurring my own travels, and informing my own writing. To this day, a dog-eared copy of Chatwin’s The Songlines (his exploration of sacred Aboriginal storytelling) is never far from my desk. And the mere mention of brown bears conjures Herzog’s haunting Grizzly Man (a documentary about a man’s fatal obsession with Alaskan bears). Even as I reread the opening paragraphs of this article, I’m slightly embarrassed to note the echoes of a Chatwin story or a Herzog screenplay. But that’s the power of great storytellers—their distinctive voices embed themselves in their audiences.

(Related: These travel books take readers on real-life adventures.)

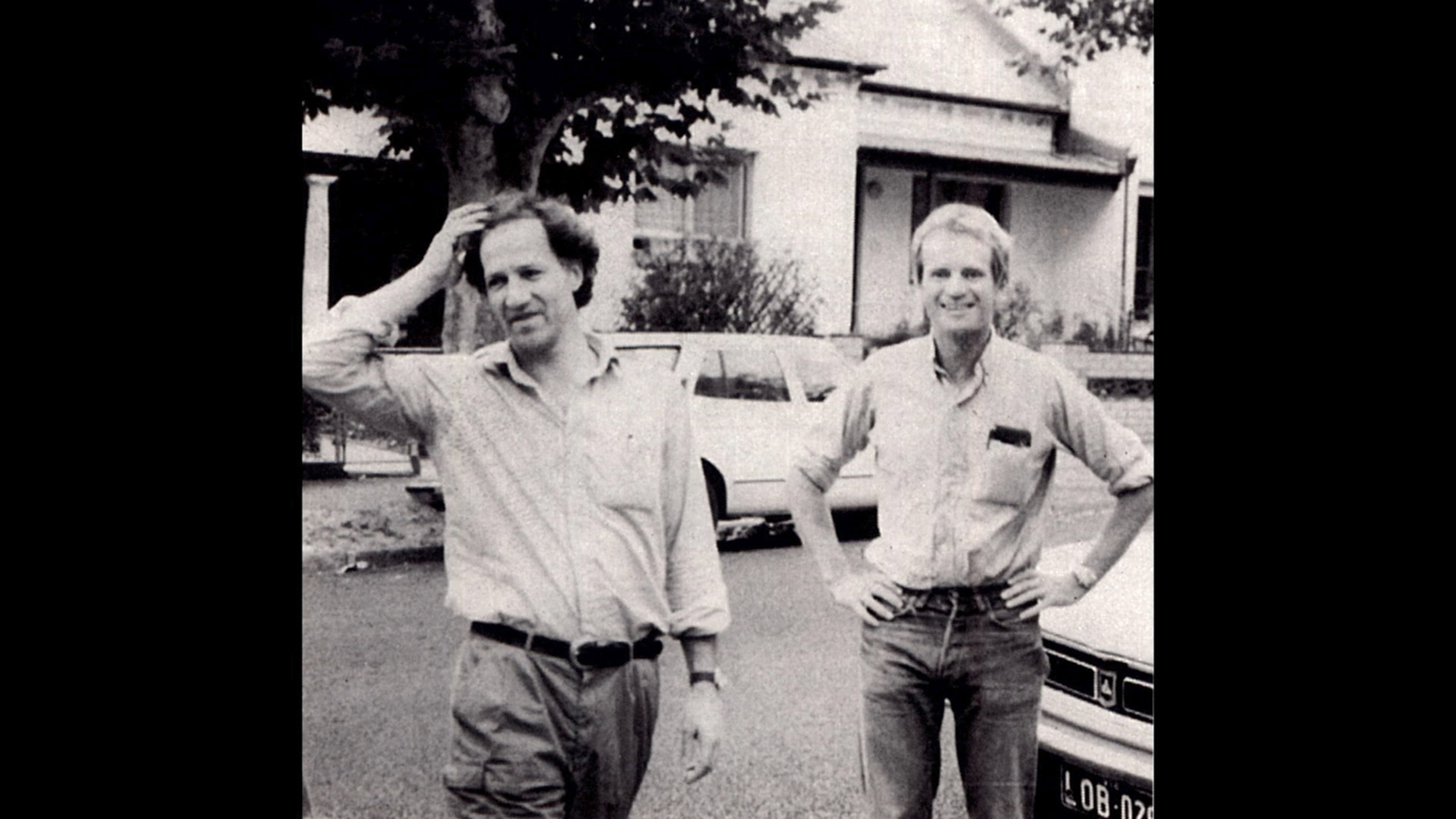

The fountainhead for Chatwin’s and Herzog’s engrossing stories, of course, was their travels. Each had a penchant for disappearing, often for weeks, sometimes months, following their bottomless curiosities into the most remote corners of the planet—the sand seas of the Sahara, the mountain fastnesses of the Hindu Kush, the endless grasslands of the Eurasian Steppe, the sunbaked barrens of the Outback. In fact, it was in Australia when their paths first crossed in 1983. They remained in touch until Chatwin’s death, which was later revealed to be from HIV/AIDS.

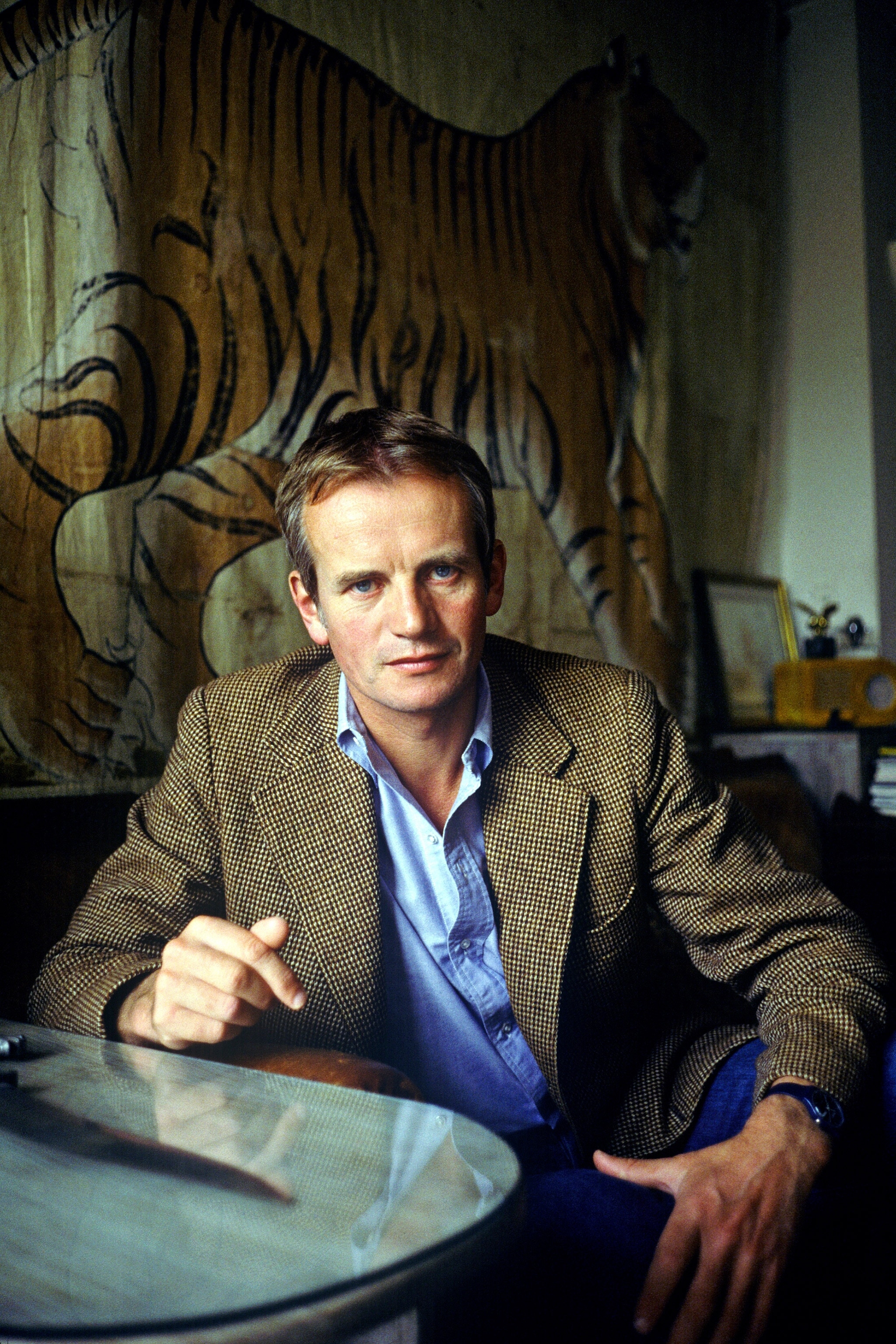

For the 30th anniversary of the writer’s death, the BBC asked Herzog, now 77, to make a documentary about his old friend. Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin is available to stream starting August 26.

I recently caught up with Herzog via Zoom from his home in Los Angeles, where he talked about his singular friendship with Chatwin, the beauty of traveling on foot, and why he makes such a good villain on camera.

How did you meet Bruce Chatwin?

We met in Melbourne, in Australia. I was in the last few weeks of preproduction for the feature film Where the Green Ants Dream in 1983. He was in Australia promoting one of his books. I contacted his publishing house, and they said “He’s somewhere in the Outback.” I said, “If by any chance he makes contact with you again, tell him I am searching for him.”

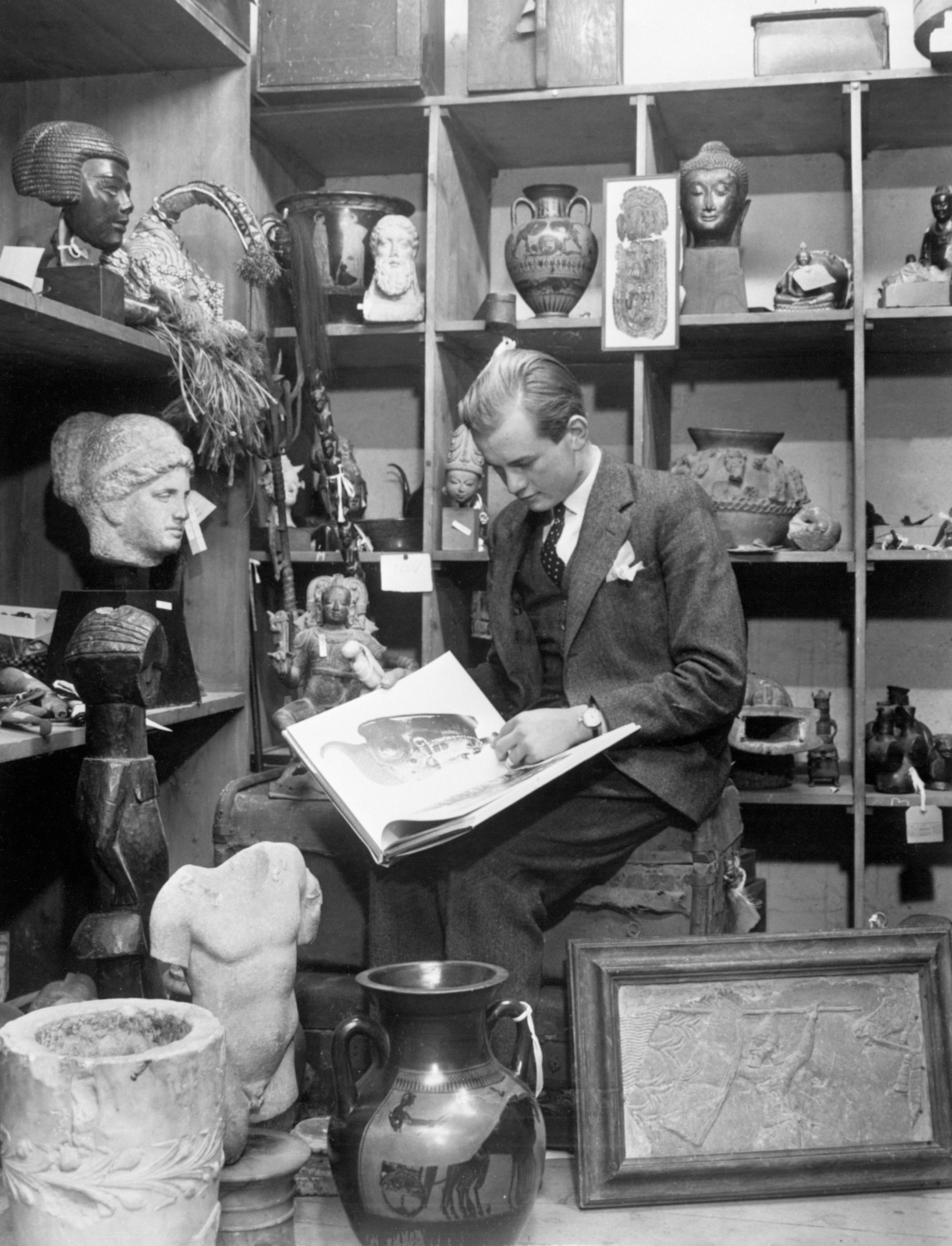

I didn’t know that Chatwin even knew about my films, but at the time in his rucksack he carried my book, Of Walking in Ice, about when I traveled on foot from Munich to Paris in the beginning of winter.

He called me a few days later and agreed to meet me in Melbourne. I said, “How do I recognize you?” And he said, “I’m tall and blond. I look like a schoolboy, and I wear a leather rucksack.” We didn’t greet each other much. We started to tell stories to each other. Simply. It was a 48-hour marathon of storytelling.

What kinds of stories did you tell each other?

About traveling on foot. We instantly understood that as travelers we were on foot and nobody else was. Of course, there were backpackers, but they carried their household on their back: their tent, their cooking utensils, their floor mats, their sleeping bag. You just name it. We didn’t. We only had the utmost necessities. That forced us to connect to the world.

When I was traveling from Munich to Paris, my canteen was empty already at 10 in the morning. It was a very hot, dry day. Not a single creek or a river or a faucet anywhere. Nothing. By 5 p.m., when I was so thirsty, I had to knock at the door [of a farmhouse]. When the farmer’s wife opened the door, I simply asked whether she could fill my canteen. But people instantly recognize something special about those who travel on foot. I would be invited in and they would tell me stories from their lives that they hadn’t told to anyone. So that’s the kind of traveling that we both did.

Couldn’t you have experiences like that without walking? Why is walking so important to you as your mode of travel?

It’s how we are made as homo sapiens. We are biologically organized to cover distances on foot. That’s what we did for tens of thousands of years until we started to use horses, of course, until the mechanical age. And I would not call it “walking” because it’s not going out for a stroll or going out for a “power walk” or ambling in your city. It’s “traveling on foot.” You are reading the world, learning the essence of the world. Chatwin always liked my dictum: “The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.”

(Related: Paul Salopek was walking the global trail of our ancestors when pandemic struck.)

Chatwin didn’t seem to choose interesting places to visit so much as he seemed to chase ideas that led him to interesting places. Was this approach something that resonated with you?

It’s an attitude of curiosity. It is your sense of the essentials. It’s your sense of the absurd. Sometimes it’s a world view which shapes a world view. He had that in him. And we recognized each other because in a way, I have it in me. Look, for example, at the Conquest of the Useless. That’s a book you should read.

The book about your experiences in the Amazon making Fitzcarraldo.

It is not a book on the making of a film. It’s about fever dreams in the jungle. We went through catastrophes every single day. And when I speak of catastrophes, I mean real ones. We had two plane crashes. We ran into a border war between Peru and Ecuador. And another incident, my camp for 1,100 people was attacked and burned to the ground. And on and on and on, day after day as I moved a ship over the mountain.

Much of your work focuses on characters, both real and fictional, who are obsessed with a subject or a goal. Is Bruce one of those characters? I mean, somebody who was just overwhelmed with what he was doing?

No, I think obsession is not the right word, but he had a profound, existential, curiosity about the world. He would follow a thread, and he would not be stopped from pursuing that thread and figuring it out.

How did his death affect you? Did it affect your approach to your work?

When he was on his deathbed, he called me to come visit him. He wanted to see my new film on the Wodaabe nomadic tribesmen in the southern Sahara, which I had just finished. I brought the film, but it was a shock because he was very busy dying. He was unconscious much of the time, but he would have lucid moments, and he’d say show me the film, show me the film. I had a small projector. I showed him 10 minutes of the film, and then he would lapse into a coma again.

It was terrifying to see a man like him dying. He spoke about his legs: “My left boy is hurting. Can you rearrange my legs?” They were just bone, only spindles. He was a skeleton and his face wasn’t there anymore. There were only glowing eyes in the skull.

He would shout out in moments of semi-lucidity. “I’ve got to be on the road again. I have to be on the road again. My rucksack is too heavy.” So I said to him, “Bruce, I can carry it. I’m strong. I’ll be the one who carries your rucksack.” That calmed him. And then he would watch another 10 minutes. Eventually he watched the entire film.

He was embarrassed to die in front of me—because he was only 48 hours away from really dying—and he asked me to leave. He said to me, you have to have my rucksack. You are the one who should carry it. His wife later sent it to me. It’s not a token nor a symbolic sort of gift. I use it even now.

In Patagonia, when I was filming Cere Torre, I was hit by a blizzard on a ridge and nobody could help us. We were three men, and we had to dig ourselves into a little ice cave not much better than a big barrel. I was sitting on his rucksack, which I had on me at the time. We had no sleeping bag, no tent, no rope, no mountain climbing gear, nothing. For 55 hours we were caught in this blizzard, and for 55 hours I sat on his rucksack. It was good because I would have lost some more body temperature sitting on the ice.

It’s a practical thing for me. It’s in the little closet next to my mosquito net and my canteen. Just the essential things that I would need.

(Related: How ‘Free Solo’ filmmaker Jimmy Chin tackles fear—and family travel.)

When you do travel, what do you carry in the rucksack?

In Chatwin’s rucksack, I would carry a second pair of underwear, socks, toothbrush, just the very essentials. A canteen. I always carry a pair of binoculars. And I carry a notebook and a pen. Tiny notebooks. They fit in my shirt pocket so that I can access them instantly. I write in miniature. And sometimes I would write while walking. It’s crooked handwriting, but I still can decipher it.

What do you think Bruce would have made of this moment in history where travel’s been almost completely curtailed?

I don’t know. He probably would have welcomed it, because he was against tourism and tourism is destroying so many cultures. I have a dictum: “Tourism is sin and traveling on foot virtue.” He liked it. And now tourism is severely curtailed.

What do you make of this whole genre of the bucket list?

I don’t have a bucket list because I never planned anything.

How would Chatwin have dealt with “fake news” and the debate over who controls the narrative of a place?

By countering with even better stories.

What was it like to revisit some of these places so long after he’d been there, particularly Patagonia and Australia?

It’s depressing. Always, when I revisit locations of my films, it’s utterly depressing. I don’t know why it is, but all the magic of a place has disappeared because you have articulated it into images that are somehow a separate entity that reflect a dark glow of beauty imposed in images or in prose. I try to avoid revisiting locations of my movies.

I was struck by the scene at the beginning of Nomad, where tourists in Patagonia take their picture with the statue of the giant sloth in the cave that Chatwin made famous. What do you think he would have thought of this place becoming a kind of roadside attraction?

It’s hard to make a judgment. He described the cave and he made it known to the world. I don’t think it was within his imagination that his book [In Patagonia] would have this kind of repercussions and would attract such crowds of tourists. Of course, we both always were against mass tourism.

With all the travel lockdowns, do you still have projects in far-flung places?

There’s a project that I have to do on a Philippine island, a feature film. But at the moment I can’t travel. I can’t venture out with a camera.

(Related: If you must travel now, here’s how to make it safer.)

My kids would never forgive me if I didn’t ask a question about your recent role as “The Client” in The Mandalorian. Is there any chance you’ll turn up in any more Star Wars films? I thought you made a perfect villain.

I’m even more evil in Jack Reacher [laughs]. For me to get involved as an actor in a film, there have to be a few criteria. The screenplay has to make sense. The caliber of the filmmakers has to be high. And I have to know I would be good for the role, that I could really deliver. As a villain, I always deliver. You will never find me in a romantic comedy.