Tokyo listening bars—what are they and where to find them

The phenomenon of listening bars originated in Japan — and in frenetic Tokyo they offer a unique way to switch off, wind down and find inner peace.

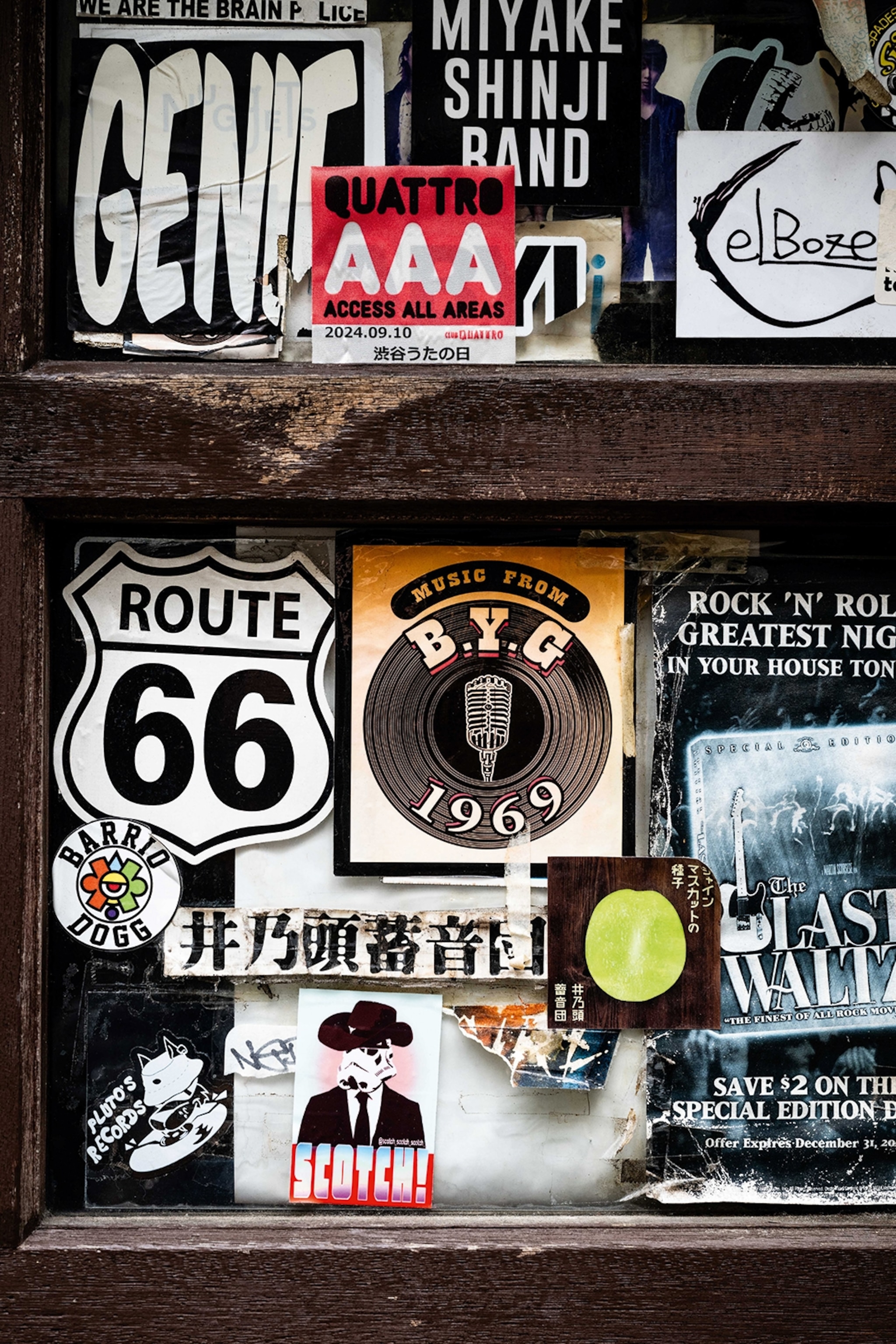

In the Tokyo pleasure district of Shibuya, amid the nightclubs and the love hotels, an electric sign flickers a pink slogan: ‘Music from the BYG’. I walk through the door and find myself inside a classic rock ’n’ roll drinking hole. Twentysomethings sit clustered around wooden tables, leather jackets studded with spikes and hair sculpted into rockabilly pompadours. Half-smoked cigarettes billow plumes of smoke from silver ashtrays. Monochrome renderings of Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan snarl down from the walls, between shelves crammed with well-thumbed record sleeves.

It doesn’t take long, though, to realise there’s something different — and surprisingly peaceful — about this bar. Beyond a few murmured exchanges, nobody is speaking; many of the punters have their eyes closed and their ears bent towards the back wall, which is entirely made up of high-spec speakers playing The Rolling Stones’ Street Fighting Man in crystal-clear quality. The lack of conversation and the attention paid to the music gives the place a serene, respectful atmosphere, despite the raucous rock music emanating from the speakers. BYG is a listening bar — a Japanese phenomenon where recorded music is the main event, rather than just the background noise, and is delivered through speakers of the very highest quality. Playlists are usually curated by the owners, although in some bars, like BYG, punters can take records from the shelves and request them.

(A music lover's guide to Tokyo, the city that moves to its own beat.)

These bars can be found across Japan but are particularly concentrated in Tokyo’s Shibuya, where they provide sanctuaries of calm amid the chaos. A number of businesses dubbed ‘listening bars’ have opened in London, New York and other Western cities in recent years, but all they have in common with their Japanese counterparts are their high-end speakers and commitment to sound quality. What makes Japanese listening bars unique, and unlikely to be exactly reproduced in the West, is the reverence with which the local punters hold the music, sitting in near or complete silence without needing to be told to do so.

Beside me, tour guide Jeff Garrish, smiling with half-closed eyes, delivers his verdict: “It reminds me of a Zen garden.” A keen horticulturalist, Jeff is a Japanese American, born in Nagasaki, who’s lived in the outskirts of Tokyo for several years. “Notice how quiet everyone’s being?” Jeff says. “Personal space is hugely important in Japan. It’s the same reason perfume isn’t a big thing here — strong smells impose themselves on other people.” The same principle is at play in listening bars. “That’s the deal,” Jeff says. “I get to enjoy my experience of the music, and I don’t get to impinge on yours.”

BYG represents the more relaxed end of the listening bar spectrum — food is served and no one actually tells you off for talking. But Jeff also wants to show me somewhere more serious, so we step out once more into the chaos of Shibuya. Famous as a red-light district, Shibuya has a remit that extends into all areas of entertainment. Music spills from the open windows of tower blocks, whose floors house raucous bars, ramen restaurants and gig venues, their names declared on lurid neon signs.

We walk for a few blocks and then descend into another dark basement, home to Pres Jazz Bar. Dimly lit by lamplight, its polished wood bar lined with leather stools, the atmosphere is all-enveloping. On one wall are painted murals of jazz legends Billie Holiday and Lester ‘Pres’ Young, after whom the bar is named, and covering the back wall is a sight that unites all Tokyo listening bars: shelves supporting thousands of vinyl records and CDs. The reedy strains of John Coltrane emanate warmly from speakers in a darkened corner. Pres is a jazz kissa — the type of venue that really set the listening bar craze alight in the post-war years, when US jazz records flooded into Japan. They quickly found an audience with Japanese music-lovers and multiplied, aided by Japan’s pre-existing cultural inclination towards serious hobbies, respect for the arts and appreciation of high-quality technology.

The barmaid, Kana Sato, hands us both a hot hand towel, takes our order of Japanese whiskies and begins chipping ice cubes into specific shapes whose different melting times complement the flavour profile of our chosen drinks. It’s the kind of attention to detail that infuses Japanese life, including the culture of the listening bars, with their painstakingly curated record collections. I ask Kana in a low whisper if talking is allowed in here. She looks slightly confused. “Well, yes — but then people won’t hear the music properly,” she says. In this way, thanks to the fact that Japanese culture prioritises social harmony, the listening bars police themselves.

There’s one more place Jeff wants to show me: Lion Café. Opened in 1926, it’s the spot where the listening bar phenomenon began and exclusively plays classical music. We navigate the madness of the Shibuya Crossing — the world’s busiest pedestrian crossing, with 3,000 people streaming across it at any given time — and turn down a quiet alley to find ourselves in front of a mock-medieval stone building resembling a European church. We walk in, where the ecclesiastical atmosphere is only enhanced by a pin-drop silence and rows of seats that face, pew-like, towards a central altar. It’s topped not by a holy cross but by a set of huge, wood-panelled speakers.

A grey-haired man approaches and I order a lemonade (no alcohol is served here). We’re still in Tokyo’s seediest district, yet the atmosphere in here is so quiet and reverential that a whispered order for a soft drink feels naughty beyond reproach.

Moody string music plays, in exquisite quality, through the giant speakers. When the movement ends, a waitress comes to the front of the room with a microphone and says, “That was today’s final piece, by German neoclassical composer Paul Hindemith.” The remaining punters file out in silence, and I get talking to Naoya Yamadera, the elderly man who’d greeted me on my arrival. He’s the fourth generation of Lion’s manager, having inherited the role from his father, and he says stewardship of the place is his main motivation for continuing to run it. “It’s all about preserving places like this — protecting their special atmosphere,” he says, then breaks into a conspiratorial grin. “I’m not bothered about classical music. I sit in front of the speakers after closing time and listen to Sgt Pepper.”

How to do it

This story was created with the support of Inside Japan.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).