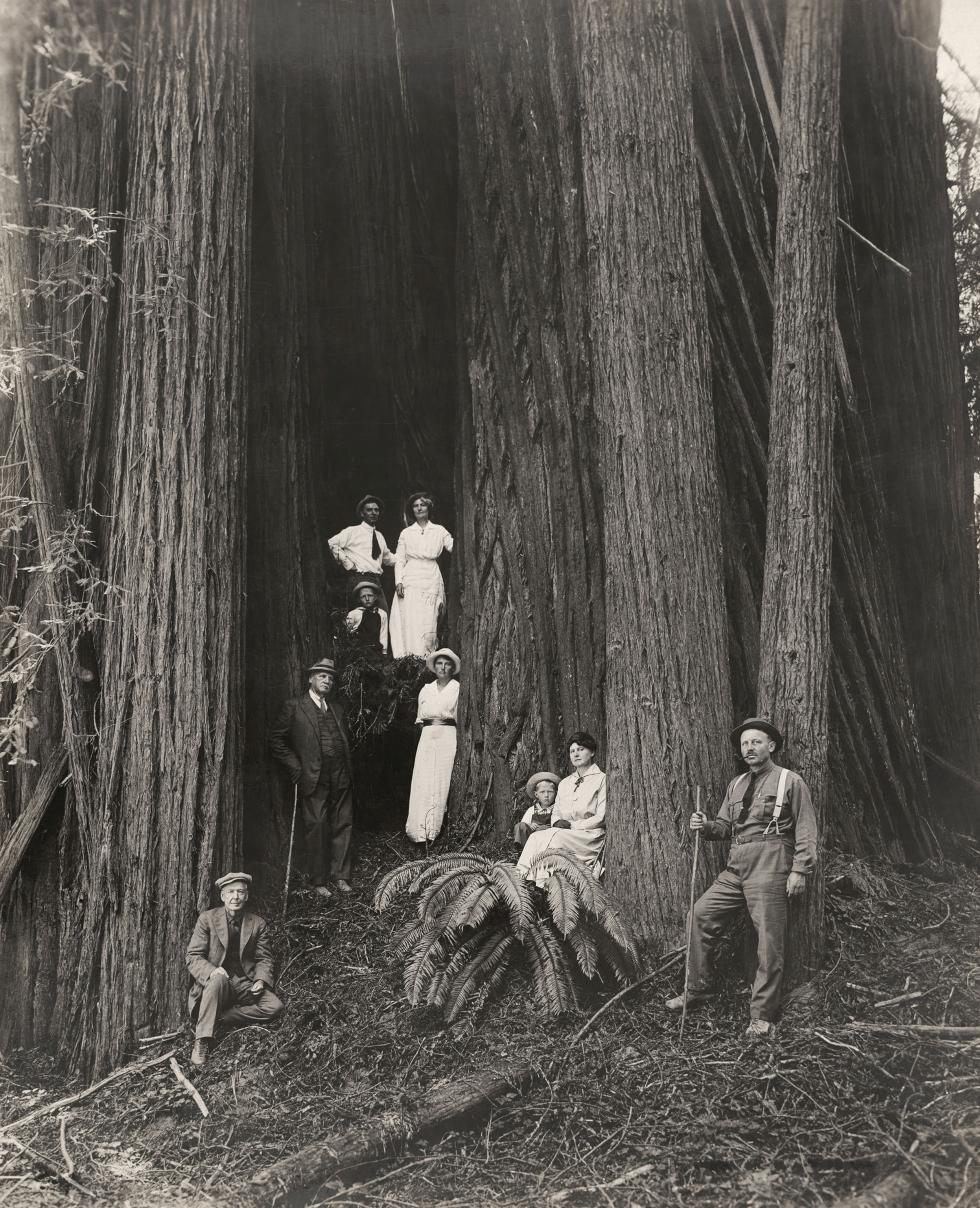

See how women traveled in 1920

Women’s Equality Day celebrates the year the 19th Amendment gave (most) women the right to vote—but travel was often a different matter entirely.

What was it like for women to travel in 1920? Well, that all depends on who you were and where you were going.

That was the year many American women won the right to vote with the 19th Amendment, now remembered on August 26 as Women’s Equality Day. The amendment didn’t apply to all women, since Native people, Asian immigrants, and black women in the south still couldn’t vote for decades. And women's safe access to travel was similarly patchy.

If you were married and traveling abroad, your husband probably had one passport that identified both of you as “Mr. John Doe and wife.” That’s because only unmarried women could get a passport with their birth name. If a married woman applied for her own passport to travel alone, it would still arrive in her husband’s name as “Mrs. John Doe.”

But really, you weren’t supposed to travel alone in the first place.

“Whether she’s traveling alone in the name of her husband or whether she’s unmarried and traveling alone … in all situations it represents something sort of outside of the norm,” says Craig Robertson, a media historian at Northwestern University and author of The Passport in America.

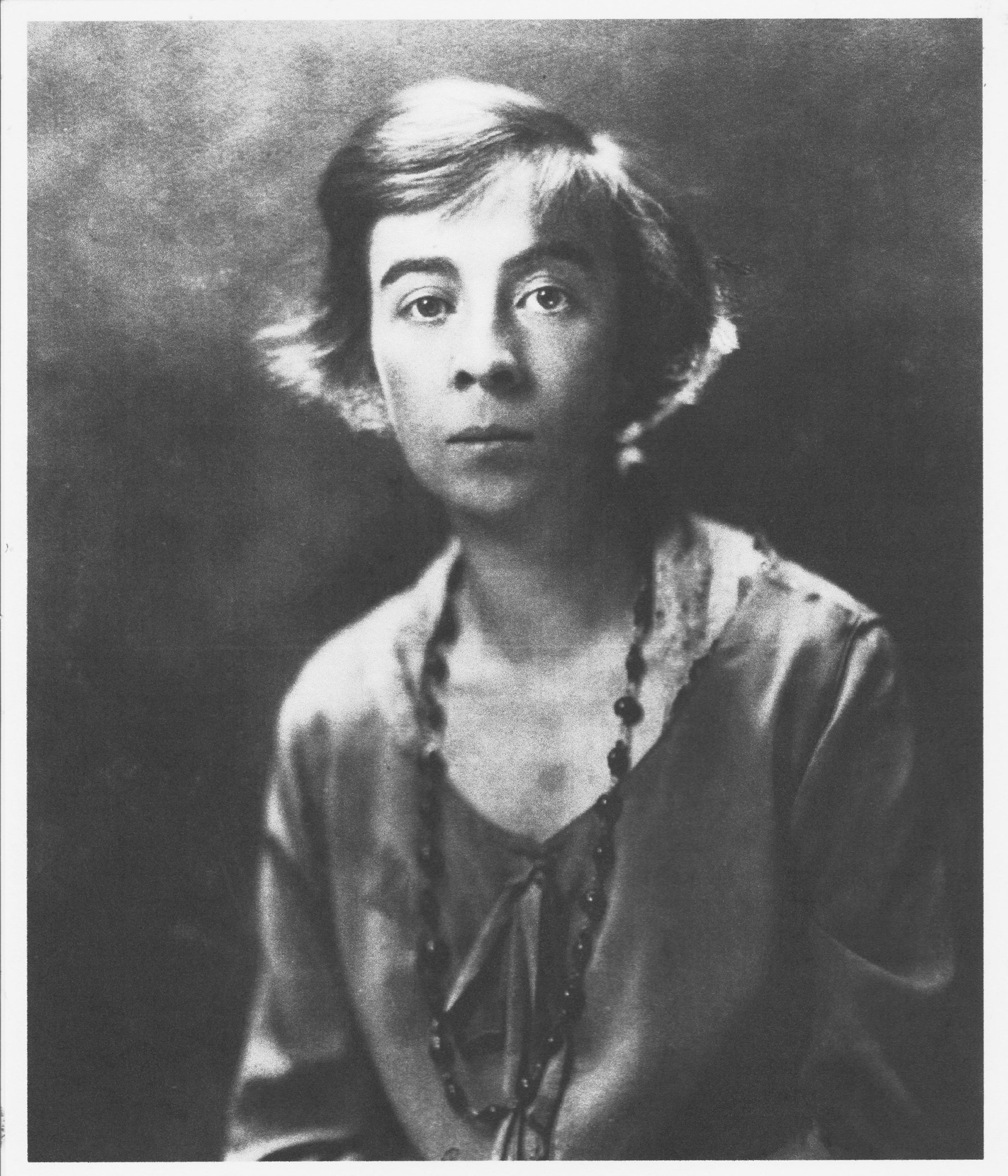

Despite this, there were still women who traveled alone in 1920, some of whom didn’t like carrying passports in their husband’s name—like journalist Ruth Hale, who founded the Lucy Stone League in 1921 to combat the issue. Four years later, the league helped writer Doris E. Fleischman became the first married woman to receive a passport in her given, or “maiden,” name.

Not everyone had equal access to international travel. In particular, Native Americans weren’t U.S. citizens and couldn’t even travel freely in their own nations. But for black women who could afford it, international travel provided a way to evade racist constraints in the U.S. In 1920, Bessie Coleman obtained a passport and went to aviation school in France because no U.S. flying school would accept her. It was only by getting out of the country that Coleman became the first black woman in the U.S. to hold a pilot’s license.

However, the U.S. also denied a passport to at least one prominent black woman. Activist and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a frequent traveler to Europe in the 1890s, when passports weren’t as necessary. But 1918 was a different story: The U.S. refused to issue her a passport to travel to the Paris Peace Conference because it considered her “a known race agitator.”

Wells-Barnett was certainly no stranger to travel discrimination in the U.S. In the 1880s, she made a name for herself by suing a train company that kicked her off of a first-class ladies’ car (she won, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the ruling). Black women faced the same discrimination on public transportation in 1920, a period when many moved north during the Great Migration.

“Certainly you see a lot of fiction of the Harlem Renaissance dealing with those kinds of travels … women going both west and north for opportunity,” says Shealeen Meaney, an English professor at The Sage Colleges.

The Harlem Renaissance writer Nella Larsen “was particularly interested in mixed-race women and the issue of racial passing,” Meaney says. Her novellas Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929) feature traveling women “who experience both gaining entry to white environments and being excluded from white environments based on whether individuals recognized them and labeled them as black or white.”

Automobiles provided an alternative to public transportation, but they weren’t always a safe choice for black women who had access to them. The Negro Motorist Green Book—which detailed where it was and wasn’t safe to stop in the Jim Crow South—wouldn’t come out until 1936. And so although black resorts in the north and south provided a safe place for black Americans to vacation, driving to them was dangerous if you didn’t know where you could safely stop for gas.

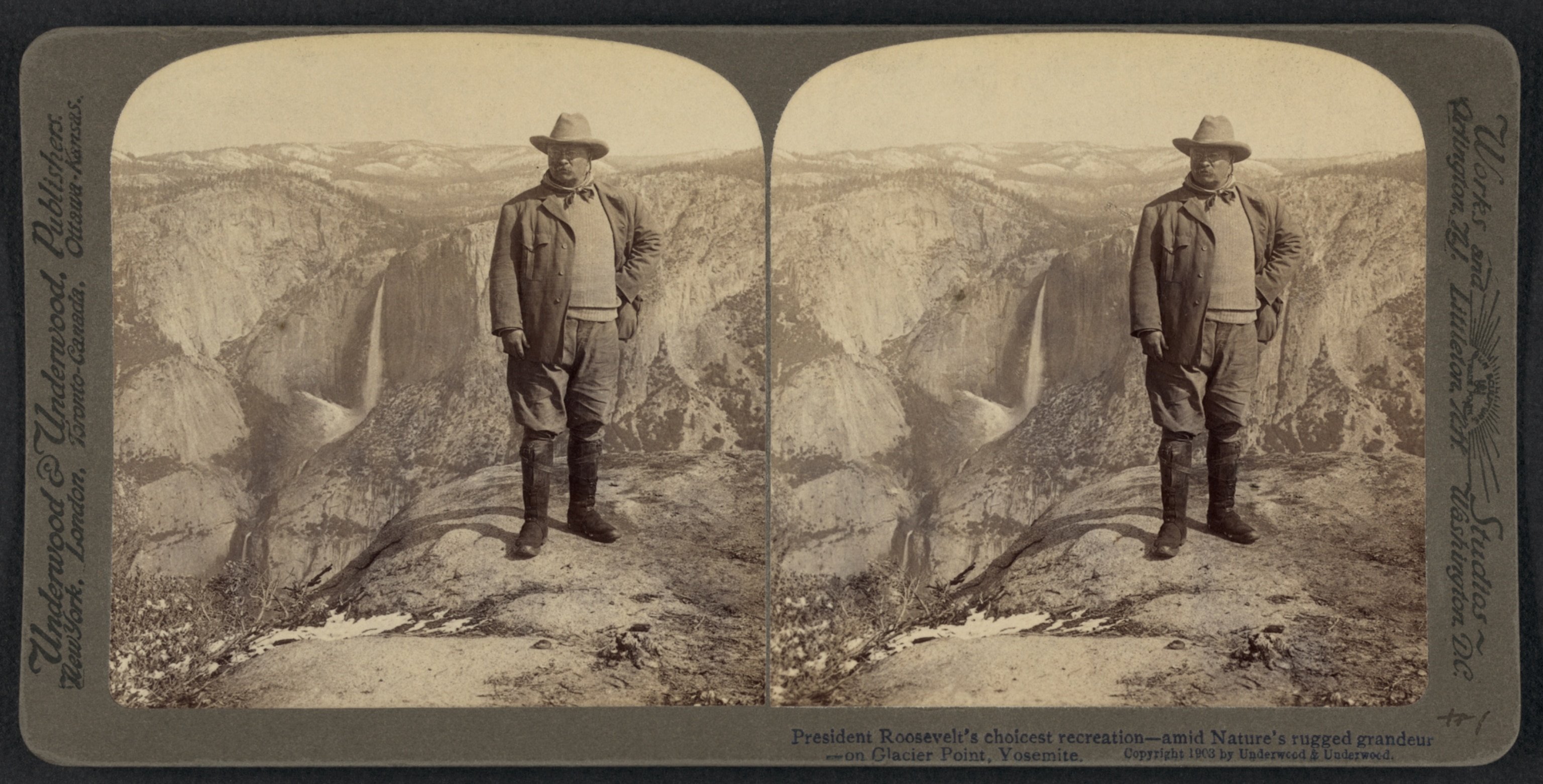

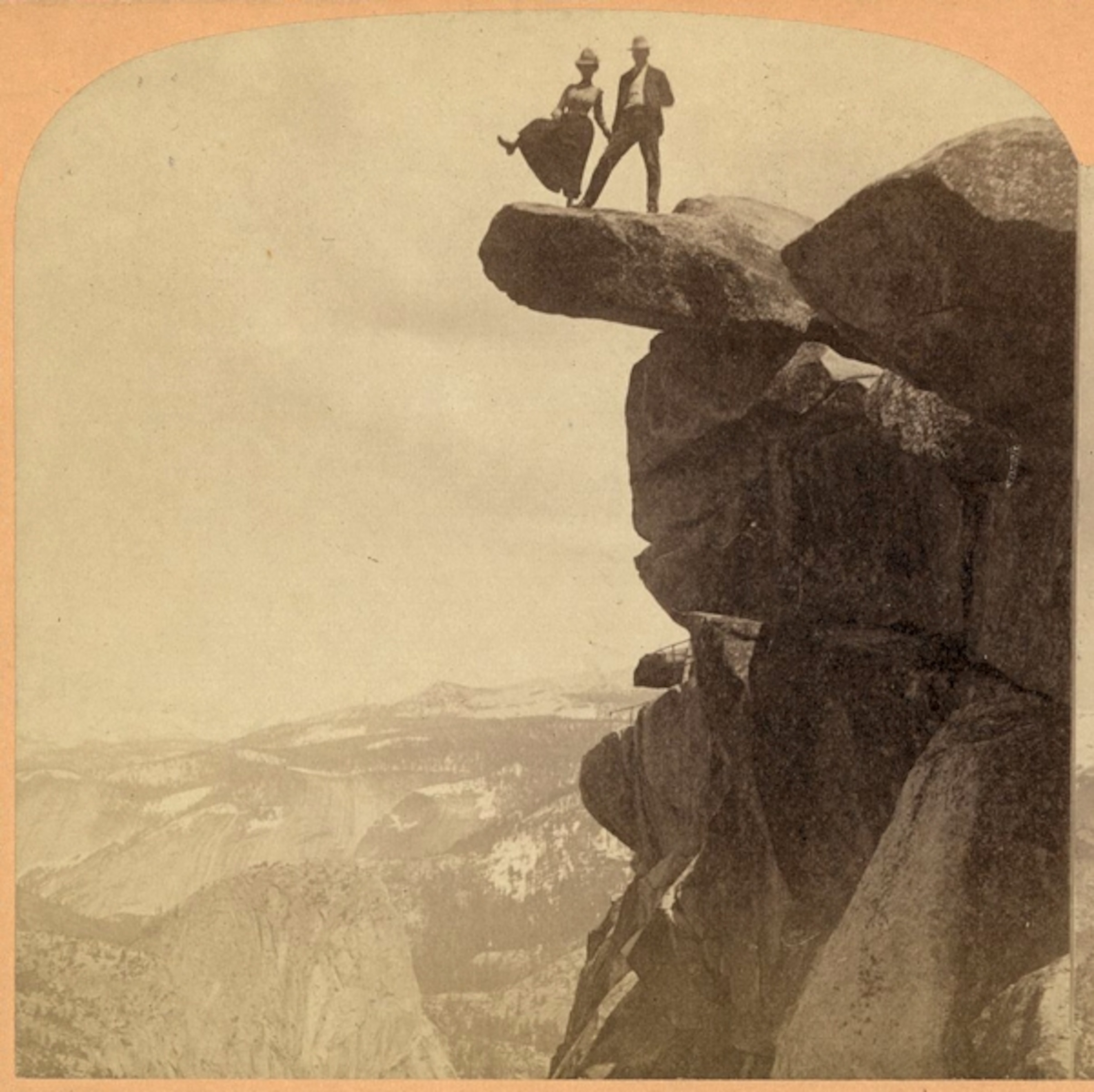

In contrast, middle-class white women who had access to cars around 1920 might take a cross-country trip with their friends over the summer and publish travel writing about their car trips. Writer Maria Letitia Stockett even seems to have anticipated the United States’ largest car film franchise—she titled her road trip narrative: America: First, Fast, and Furious.

Much like voting rights, travel wasn’t the same for all women in 1920. White women could participate with much more freedom than black women, who could vote in the north but couldn’t in the south until 1965. Similarly, Native women weren’t citizens until 1924 and didn’t win full voting rights in every state until 1962. So when you throw your Women’s Equality Day rager this Sunday, remember that it’s not just the first victory that’s important—it’s all of them.