Going to Mars Could Define Humankind in Decades Ahead, Author Says

Space pioneer Elon Musk plans on going to Mars and making it home.

Are we all Martians? Will we one day be taking our vacations there? Is extraterrestrial life not just the stuff of science fiction?

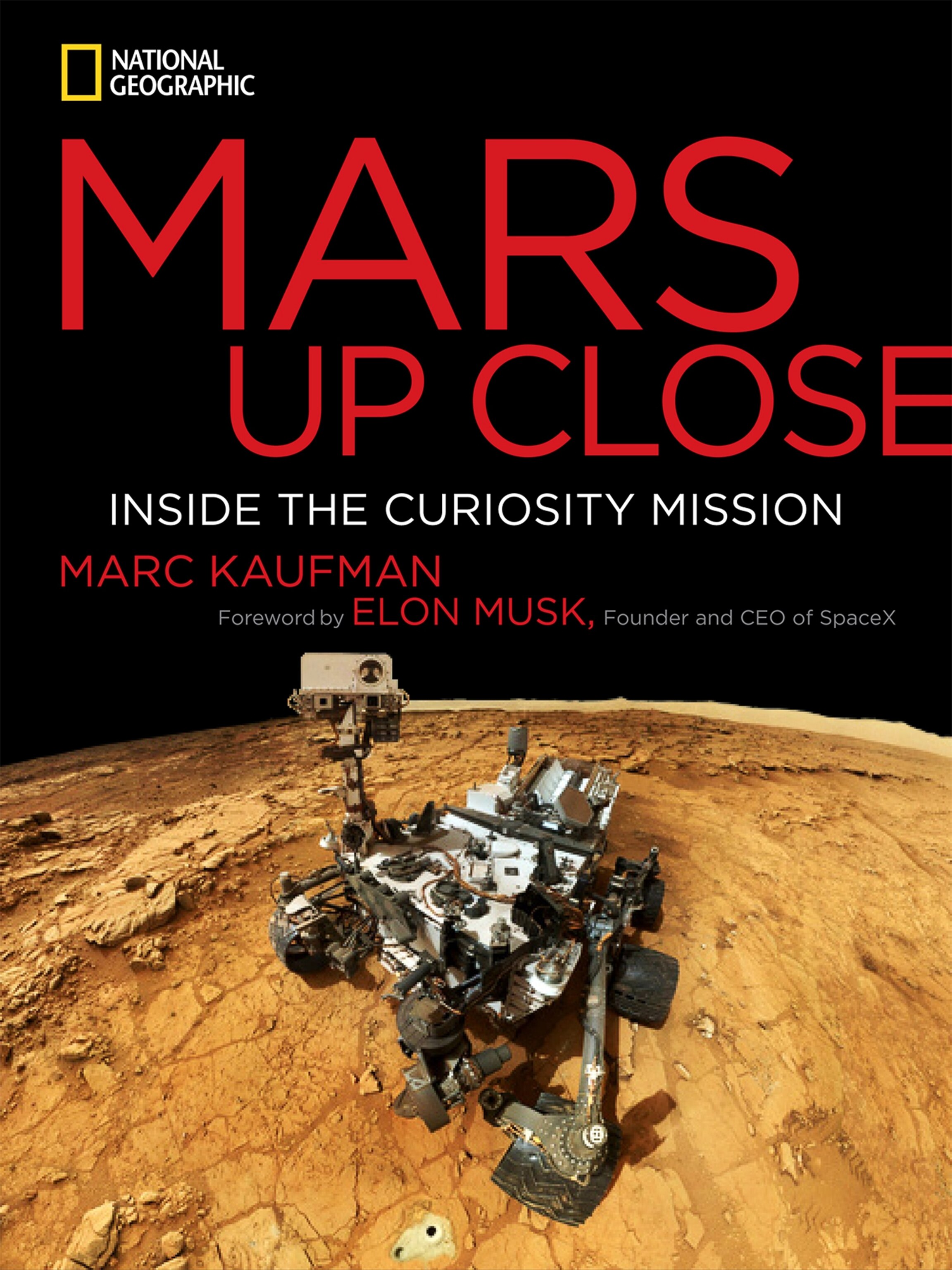

These are some of the questions award-winning science writer Marc Kaufman explores in his new book, Mars Up Close, about Mars and NASA's Curiosity mission, which showed us the red planet as we'd never seen it before.

Here he talks about how PayPal and Mars are connected, why it's important for humanity to send manned space flights there, and how a seemingly barren planet normally associated with war might turn out to be the mother of us all.

Your book opens with a jaw-dropping quote from Elon Musk: "In the next few decades I plan to travel to Mars and make it my home." Is that really feasible?

Let's just say that a lot of things would have to go right in order for that to happen. There are some big challenges. But the architecture for sending humans to Mars is entirely understood. The issue is: Is there money? And is there public support? Though he has the advantage of potentially doing some of that on his own.

Tell us a bit about Elon Musk.

He made his initial money with PayPal. Then, as he explained to me, he thought, "I have all these millions of dollars, how can I be a useful person in this world?" He was still quite young. And there were three things he thought most important. One was an electric car—thus Tesla, often described as the best car ever created. Second was SpaceX, which was a way for the private space industry to really blossom.

Now, against all odds again, he has contracts with NASA to bring cargo up to the International Space Station. He's also building a heavy-lift rocket that could indeed take someone to Mars. He's also the CEO of something called Solar City, a solar panel company, which he felt was needed in terms of new ways of dealing with the energy situation. He's in the process of selecting a site to build a giga-factory, to be the largest battery factory on Earth.

By chance, we're talking a week after NASA announced they've successfully tested an "impossible engine." Could that be significant for humans' flight to Mars?

One of the major issues is that, using current technology, it takes about nine months to get to Mars, and we know that the radiation exposure for that time is probably in the hazardous range. It may not kill you, but it would make you a fairly sick puppy. And so they need to get there quicker. The other obstacle is the life support for human beings when there.

And then, getting away again. It turns out that leaving Mars is very difficult. Even though the atmosphere is quite thin, it still is an atmosphere. So it's not like being on the moon, where they were able to just shoot up, back in the Apollo days. They'd need a fairly sophisticated and powerful rocket to get them out. They don't know how to do that right now.

They also don't know how to land something as big as a space capsule. Curiosity famously landed with a sky crane, which was a huge step forward. They dropped a 1,000-pound vehicle onto the surface of Mars, which was much larger than anything before. But to send humans to Mars, you're talking about 20 to 30 tons.

Tell us about the Curiosity mission.

The main goals were to determine whether or not Mars at one point was habitable, and to locate, if possible, organic material, which are the carbon-based compounds that are the building blocks of life as we know it, and we would assume would be the building blocks of life on Mars, if there was ever life there.

Remarkably, after landing, instead of going to what was planned as their primary destination, Mount Sharp, this three-mile-high mountain in the middle of the crater, they had seen something from orbiting satellites that appeared very interesting. It was the lowest point in Gale Crater.

And there were all kinds of geological signs that said, Look at me, look at me! So they made a pretty dramatic and risky decision to go in the opposite direction soon after landing. They went to what came to be called Yellowknife Bay, and what they found was truly astounding. It was basically ancient mudflats. And that meant there was once a lot of running water there, because they also found a river coming down into it.

The pH of the water that once had been there was neutral. It also had other chemicals in there that bacteria could use as energy sources. So they concluded there had been a lake there at one point—we're talking about three and a half to four billion years ago—and that this region, and probably other places on Mars, had indeed been habitable. Doesn't mean they were inhabited. But they were habitable.

Tell us about some of the "mission makers," the people that made the Curiosity exploration possible. Adam Steltzner is not your typical NASA geek, is he?

No, he's an incredible character, in the best sense. He had a kind of Elvis pompadour at the time, and he wore ear studs. He had played in a rock band for a long time but had been a bit of a lost soul until he had a kind of epiphany driving home one night. He saw something in the sky he didn't understand and wanted to know about. And that led him into astronomy and then into engineering.

Another amazing person was Jennifer Trosper. She's an engineer, and the whole time this thing was landing, she was also looking after two children, working 24 hours a day, with a family at home.

The moon's association in mythology is overwhelmingly female. Mars has always been associated with masculinity and war: the Greek god, Mars attacks, Martians, etc. Has this warped our understanding of the planet?

Mars has that reddish hue, which seems to connote anger or blood. But what Curiosity has revealed, to some extent, is that at around the same time life was beginning on Earth, Mars was equally hospitable. Indeed, the conditions were probably more conducive to life on Mars at that time than they were here. So some have theorized that life actually began on Mars: that some rock with life in it, like an asteroid, hit the planet, went off into space and then potentially landed on Earth and—boom!—life begins. [Laughs]

In other words, we're maybe all Martians. To me, that's the take-home message of Curiosity—that rather than being this male, violent, harsh place, Mars is potentially our mother. Or at least our cousin. Or sister.

To put humans on Mars would cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Why should any government want to spend that money?

[Laughs] Utterly appropriate question. Though that would actually be hundreds of billions over decades, doing a variety of different missions, not just one mission. The logic for it, as many see it in the space world, and I came to see it also, is that it's a challenge that will define us. And by us I mean both the United States and other nations. It's clear that the U.S. itself can't do this alone. It needs—and is increasingly cooperating with other countries—the EU in particular but also Japan and India. Russia has also been a very good partner in the past, but that may have fallen apart because of Ukraine. But putting that aside, this magnificent challenge, like going to the moon in previous generations, could define humankind.

How did work on this book change your perspective on life?

I'd written a book about astrobiology, which is the hunt for life beyond Earth, and that was what led me to this to some extent. One of the things brought home is how we need to think in astronomical time, where a billion years is nothing.

And the amazing thing about Mars is that it has changed much less than the Earth has, where human life has changed everything. Conditions are similar to what they were four billion years ago. So it's quite possible that one day scientists will be able to say: "We've detected remnants that tell us there was once biology here." It's very hard. It requires both the instruments and a leap of the imagination.

So if things continue, if more missions go and more nations get involved, I think it's quite possible they'll discover that there once was life on Mars. And that would be one of those moments, like when Copernicus said the Earth isn't the center of the universe. It changes everything. Because if there was a genesis of life on Earth, and also a separate genesis of life on Mars, it means that it's almost impossible that there aren't a lot of other planets where there's life. We might not be able to see it at any given moment, because astronomical time is so vast. But it would suggest very, very strongly that there's life out there.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.

Watch a live-stream event at National Geographic headquarters on Tuesday, August 5, at 7:30 p.m. ET or follow along on Twitter using #OurUniverse.