David Gruber: Seeing the Ocean in Neon

Researcher discovered a never-before-seen world of glowing ocean creatures.

David Gruber found a secret world under the sea—and it glows.

His expeditions have turned up hundreds of shimmering creatures, all showing off for one another with a mysterious fluorescence. It's an underwater display that had never been seen before.

And it's not just beautiful. Gruber's work offers another reason to save ocean life that we are just beginning to appreciate and understand. Some of these unusual animals, he thinks, might hold keys to medical breakthroughs.

But first we have to identify them. That's why when he's on land, Gruber designs technology to revolutionize ocean exploration, such as special photography equipment to capture fluorescent light that the human eye can't normally see.

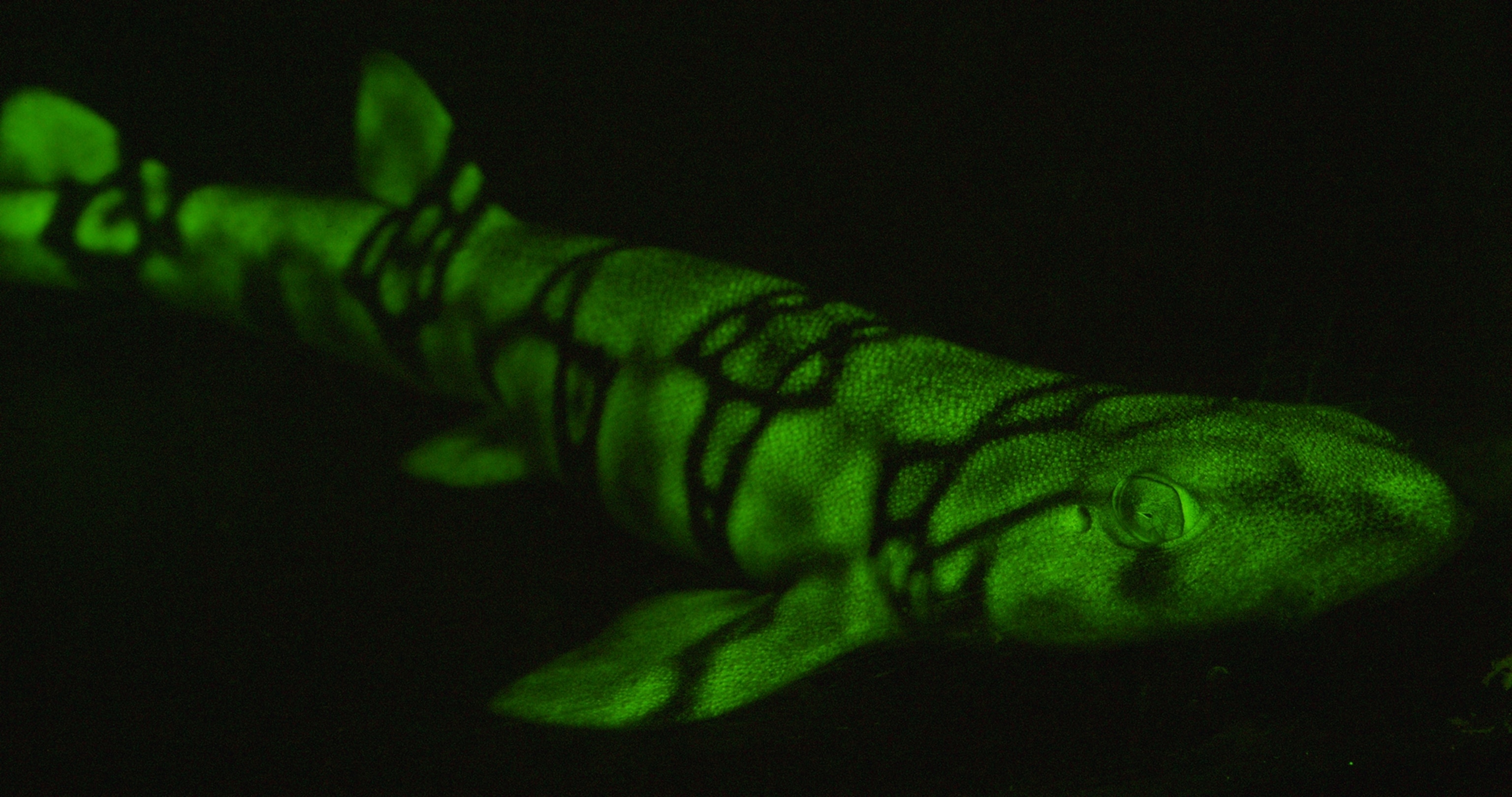

An accidental discovery set his research in motion. While designing an exhibit for New York City's American Museum of Natural History, Gruber made hundreds of photographs of the same coral reef by day and by night to capture its fluorescent glow, a phenomenon common for those varieties of coral. But in one image, a small, bright green eel pierced the darkness.

"It was so extremely fluorescent it didn't seem real. We'd never seen anything like it," says Gruber, a research associate at the museum and a marine biologist at the City University of New York.

Gruber and his team set out to find the little green mystery in the wild. They succeeded, and found 20 other species also with fluorescent displays, including a stingray.

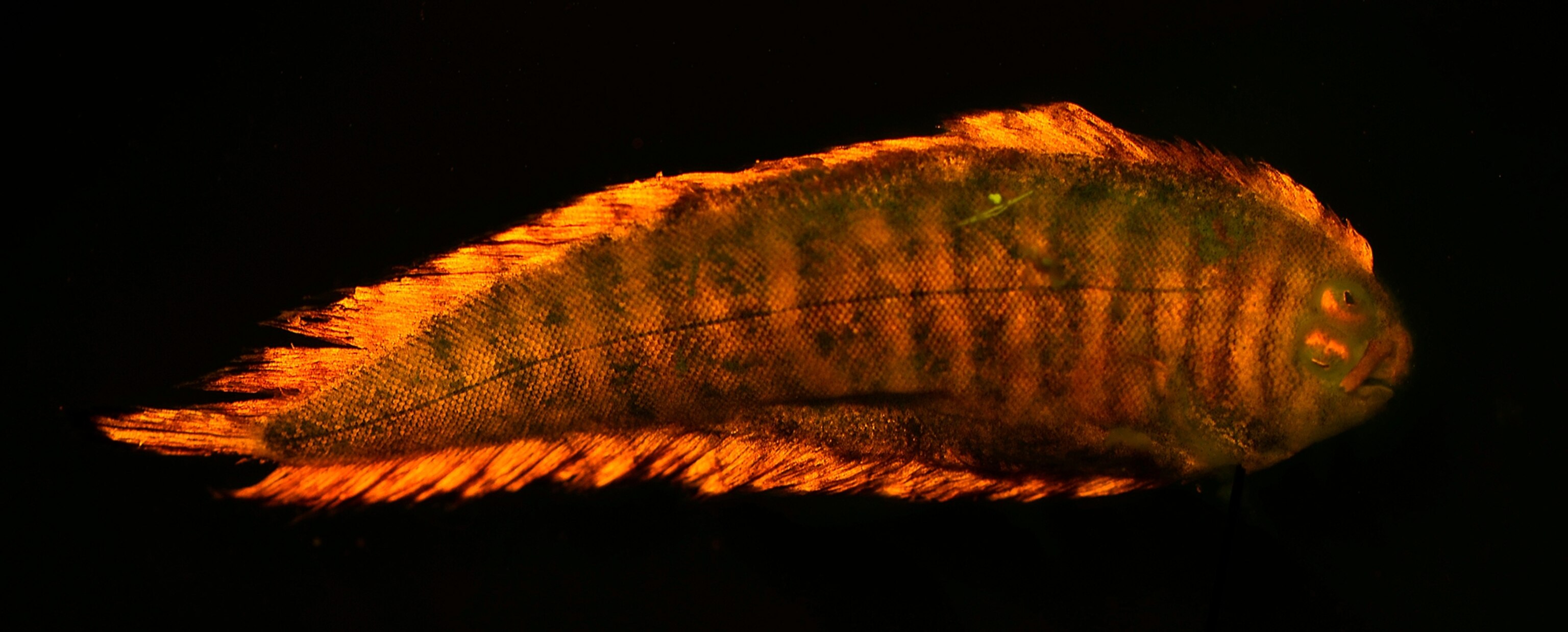

These creatures, it turns out, can see each other glowing—green, red, or orange—while human eyes can't detect their fluorescence.

Only animals with special filters in their eyes are privy to the neon light show, including many fish. For perhaps millions of years, these creatures have signaled each other in this secret language of light.

"There's a hidden layer of pattern and color that humans are just tuning in to," Gruber says. "It's a whole new way for us to perceive, and better understand, life in the sea."

Two more South Pacific expeditions revealed more than 200 biofluorescent species. "Most are shy, reclusive fish that stay tucked away, but we also identified several sharks that are brilliantly fluorescent," he says.

To reveal this underwater world, Gruber set out to photograph the ocean as it would appear to fish.

Underwater, the world looks mostly blue to human eyes. That's because water quickly absorbs most colors of light except blue. Special proteins in biofluorescent species absorb that blue light and transform it into vivid greens, oranges, and reds. But to see those fluorescent hues, an animal needs a yellow filter to block out the overwhelming blue. Many fish, it turns out, have just such yellowish filters in the lenses of their eyes.

But people don't. So to "see" like a fish, Gruber uses a yellow filter on his camera that mimics the lens in a fish's eye. Using this setup, he has captured a vibrant spectacle of fluorescent red, green, and orange patterns on sharks, eels, seahorses, and more. (See "Pictures: Fish Light Up in Neon Colors.")

"We're uncovering a secret world that some marine creatures have been tuned in to for millions of years, but we're just now beginning to notice. It opens up a whole new field of science," says Gruber.

Even more tantalizing than how they glow is why. "Coral reefs are one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet, but great diversity means great competition," Gruber says. Some fish rarely venture out except to mate, and many take that risk only in large groups by the light of the moon.

That's where fluorescence comes in. "The moonlight illuminates their fluorescent patterns and possibly allows these fish to quickly recognize and find each other," Gruber says.

Fluorescence is useful for more than just "fish talk." Fluorescent proteins from jellyfish and corals are used every day in medical research, lighting up various parts of cells to help scientists understand the inner workings of life.

Gruber's discoveries could lead to more breakthroughs in medical and cancer research. By finding a huge trove of new biofluorescent species, his team is expanding the reservoir of fluorescent proteins that researchers could use to peer into cells.

In the deeper, darker realms of the ocean, many animals can produce their own light. Instead of fluorescing, which requires some ambient light, these animals glow like lanterns in a process called bioluminescence. Gruber is studying them, too, using extremely light-sensitive underwater cameras to film in sharp resolution.

The cameras attach to submarines and to a remotely operated underwater vehicle designed specifically to study glowing life. These rigs plunge to depths of almost 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) to view bioluminescent life in remote reefs.

"We've mostly studied just the skin of the ocean, but with new technology we can now begin to examine life in the deep, dark ocean, the largest habitat on the planet," Gruber says.

One of the fun parts of ocean exploration for Gruber is inventing and trying out new gadgets. In a coming expedition, a member of his team will test a new diving "exosuit" to collect marine life 1,000 feet (305 meters) deep, far deeper than any scuba diver can go.

An exosuit is built like a submarine that protects the pilot from hazardous ocean pressure; the suit deploys thrusters to move through the water and uses robotic hands to carry out tasks.

"Each time we go deeper, we encounter new species," he says. "The oceans cover more than 70 percent of our planet, and with new tools to bring humans beneath it, there is so much waiting to be discovered."

Gruber's enthusiasm for glowing sea life is infectious. The "Creatures of Light" exhibit he helped create was the American Museum of Natural History's most visited temporary exhibit. An app and blog further extended its popularity, and he's reaching out to new audiences by collaborating with artists.

"People want to protect things they love and understand," he says. "Reefs are one of our world's most threatened environments. The more I can share the amazing animals and behaviors I get to explore, the more people may be inspired to help conserve them."