Minority Religions in the Middle East Under Threat, Need Protection

Religion is humanity's most powerful binding agent, author says.

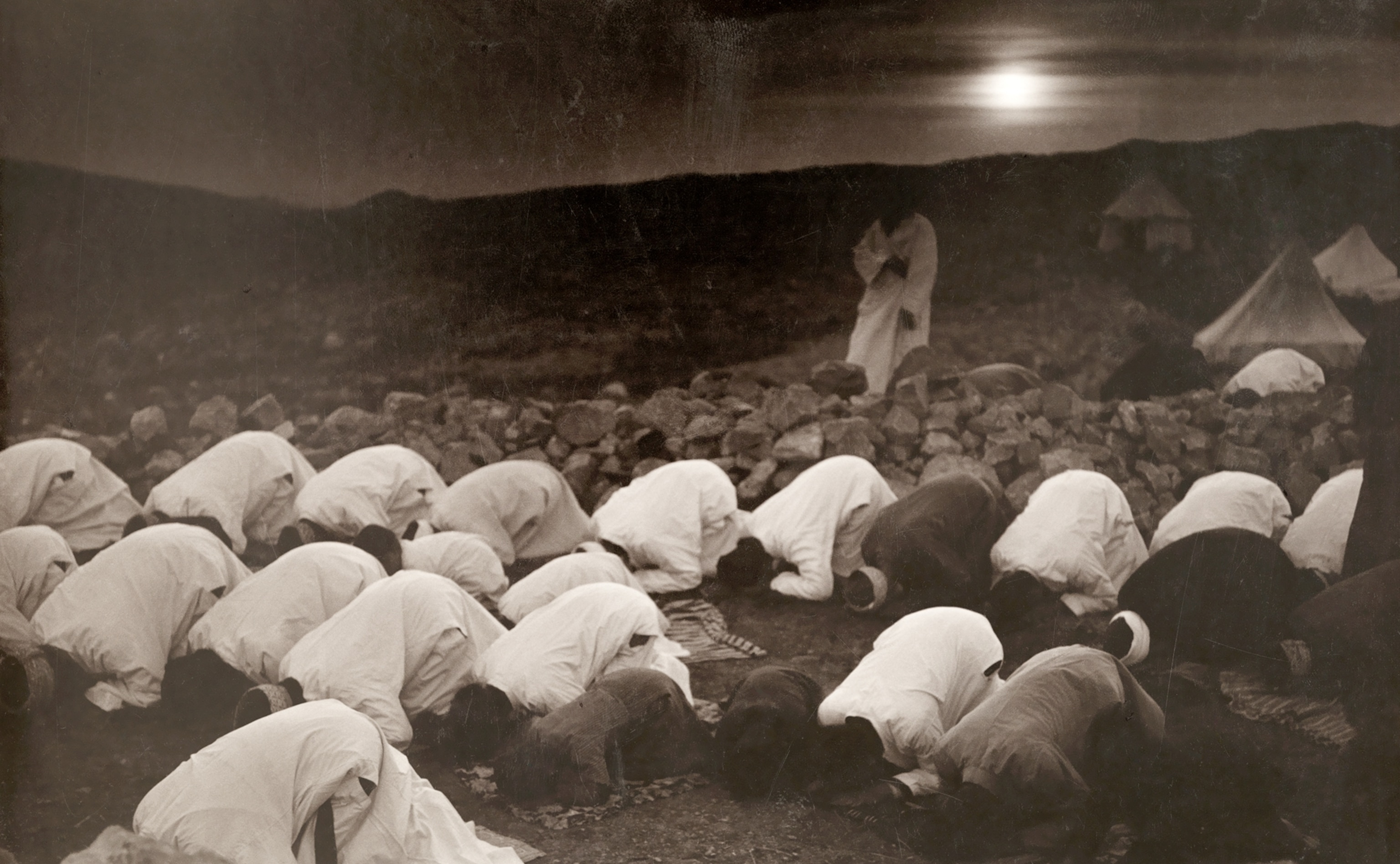

In August, our television screens were filled with biblical images as tens of thousands of Yazidis, an ancient Kurdish minority, fled into the largely barren Sinjar Mountains of northern Iraq to escape Islamic State militants, who regard them as devil worshippers.

The Yazidis are one of many minority religious groups that have survived in the Middle East for thousands of years. Others include the Copts, the Samaritans, and the Zoroastrians. But with the increasing radicalization of Islam and other political pressures, these groups face an uncertain future.

For his book, Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms, former British and UN diplomat Gerard Russell spent several years traveling to remote corners of the Middle East where these faiths hang on. Speaking from his home in London, he explains what George Clooney can expect from his new wife, why Detroit is one of the best places to hear ancient Aramaic, and why it's important for us all that these minority religions survive.

Your book is about forgotten religions in the Middle East. Why is it important we remember them?

For several reasons. One, as we saw when the Islamic State [IS, also called ISIS and ISIL] attacked the Yazidis in northern Iraq in August, these religions are still persecuted, and from a humanitarian point of view we need to think about them. We also need to understand them because religion in the Middle East affects us wherever we are in the world. Islam is a global religion. To learn from its history of tolerance, as well as persecution, because both can be found, is important for understanding the future.

George Clooney recently married a British barrister of Lebanese Druze descent. What's he gotten into?

First, he has married a very lovely woman. I know Amal Alamuddin's mother a bit; she's a very talented journalist. Her dad is from a Druze aristocratic family. They're a really fascinating people. I don't know if Amal herself is very into the religion. Only 10 percent of the Druze are initiated. Most of them don't know, for sure, what their religion teaches. Those who know about it have chosen to consecrate themselves to the religion.

As a Druze you can be untouched by any obligations of the religion, though they do pretty much insist on marrying within the religion. In that sense Amal is an exception. The Druze are also exclusive in the sense that they believe they're reincarnated as each other. So if you're Druze, you can be reincarnated as Druze. But you're not going to be reincarnated as Druze if you're not one.

They're a select group who believe they have a special mission to discover truth and bring mankind to a revelation. They believe in the imminence of God, that the world emanates from God, like light from the sun. They don't believe in a creation as such. It's very much rooted in Greek philosophy, so to understand them you need to go back to Plato and Aristotle. Those are the sorts of traditions they have kept alive.

Some of these faiths date back to the Egyptian pharaohs and the Babylonians. How has geography shaped their survival?

Most obviously, in Iraq, which is a fertile place for religion, there are marshes covering hundreds of square miles in the south. The marshes were a great place in the second and third century A.D. to live a back-to-nature kind of existence, cut off from the outside world. It was very popular for what we would call cults, which, in those days, drew on Jewish and Christian ideas. That's where the Manicheans emerged, and where the Mandaeans survive to the modern day.

Are you a religious person? Or was this a quest for a religion you could believe in?

I am religious, and this book began when I lived in Egypt. I found religion to be a great source of inspiration and a way for me to identify with a community of some Egyptians. I could go to a Coptic church and find that the service, the nature of the belief, was part of the same community as back home, but with massive differences in language and culture. I found that very comforting.

If you're in a foreign country, and you really want to be part of it and get alongside the people, it can be quite difficult. There may not be easy common points, particularly with poorer people, who live in more remote places. Religion can give you that leap into the other culture, that crossing point.

You traveled all over the region, often to very remote places. Tell us about some of the highs—and lows—of your journey.

I love the Middle East, and have many friends there of all different religions. Going out to this mountain in Israel and discovering that the Samaritans aren't just people in the Bible, but exist today and still practice their faith and have their own distinctive script, was quite remarkable.

The hardest part was going to northern Iraq in August and witnessing the great distress in the Yazidi community and hearing terrible stories of suffering. I compare it to the time when Sir Leonard Woolley, the excavator of the ancient city of Ur, one of the great cities of southern Iraq, discovered a small fragment of fabric with a beautiful pattern. It had survived 5,000 years in the sand. All of a sudden it began to rain, and the fabric disintegrated in his hands. He felt such a sense of loss, because it had survived to the modern day, and there in front of his eyes, it had been destroyed. I had that feeling as I looked at these religions that had survived millennia and were now dying, almost in front of my eyes.

One of the most remote places you visited was the temple of Lalish, in Iraq. Give us a virtual tour.

It's about two hours north of Erbil, in the middle of rolling hills. In the summer, when I was there, [the hills] are quite bare. Then you descend into this wooded valley with stone buildings about a thousand years old. It's a wonderful contrast. On the day I was there, families were having picnics under the trees. The buildings, some of which are closed to outsiders, have conical, spiral roofs, which represent the rays of the sun. Once a year a bull is chased around the forecourt of Lalish. A priest whispers in its ear before sacrificing it. It's a ritual that was performed for the sun god 5,000 years ago, as we know from the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Yazidis face a vicious new threat in the Islamic State. How do you explain their rise? And do they pose an existential threat to the minority faiths of the Middle East?

The IS is a thing of ugliness that has been born in a very ugly place: the civil wars in Syria and Iraq, which came after the 2003 war. Some of the people who fight in the IS probably endured and saw terrible things before they began to fight themselves. You've got a whole generation who've been brought up in conditions of terrible suffering and bloodshed. That's the first thing to say.

The second is that it comes in the wake of a wider ideological shift in the Middle East. People have begun to identify by religion much more clearly than they did 50 years ago. And it's often a very militant and ugly form of religion, sponsored by people who take a very narrow-minded view of what religion should be and harbor a deep hostility toward those who they think are undermining the true religion.

Take the hostility between Sunni and Shiite, which is not totally unlike the Catholic- Protestant struggles of Europe's Middle Ages. Sadly, there are people out there, quite a number actually, who, if they're Shiite, very much dislike Sunnis—and if they're Sunni, the Shiites. In Egypt, a Gallup poll showed that a very small minority of Egyptians actually believe that Shiites are even Muslims.

The phenomenon of killing people is a very specific, limited problem. The much broader problem is that there is a de-legitimizing of people based on their religious beliefs. This is very dangerous. And very widespread.

Why did Europe lose its pagan faiths—yet they survived in the Middle East? Why aren't there Druids running around London?

Europe had states that were ultimately more effective. If you look at France or Germany or Britain, the state was, at quite an early stage, pretty effective at imposing itself. Think of the Domesday Book. The Middle East was quite a bit more lawless for quite a lot of time, and that's partly how these groups survived. Some of it is also topography. Where these groups survived was often the most remote places.

Another reason—and I know this is going to be a controversial thing to say—is that when Christianity arrived, the pagan religions in Europe were not very intellectually sophisticated. In the Middle East, you had a long history in which these religions had become deeply philosophized, with a deep understanding of how to think about their religion in terms of ideas brought by the Greek philosophers. They also had quite strict moral codes.

So when Islam came, it wasn't entirely sure that it wanted to get rid of people like the Harranians, who were quite useful. They knew a lot of Greek philosophy; they were very good scientists. So a lot of these heterodox religions were allowed to carry on. Some Islamic rulers even made good use of them.

Some readers may be offended by your contention that Middle Eastern cultures fight more over religion because it's more precious to them than to Americans or Europeans. Is that statement really justified?

The comparison was not meant to denigrate Western religion. I'm a religious Westerner myself. But from the first day I arrived in the Middle East, I found there's an extraordinary willingness to go the extra mile for religion. Not all of it is for good reasons. So I don't mean to say that people in America aren't religious.

But the growth of democracy in the Western world often came at the same time as people began to question religion. Could America have been founded as a nation that separated church from state in the 16th century? Or did it take the Enlightenment before that could be done?

It took a lessening of the passion that people felt about religion before it was possible to say: I'm a Catholic, you're a Protestant, and I don't mind. In the Middle East, we haven't reached that point, where people are willing to say: I'm a Muslim, you're a Christian, and I don't mind.

Religion seems to be one of the central causes of turmoil and death in our world today. How would you counter that assertion?

I would say that religion is the most powerful binding agent that humanity knows. For a brief time, in the Middle East, ideologies could do that. Communism, to some extent, did it. So did nationalism. But in the modern day, it's religion. That's true of the West too. It's only at church that I will encounter the full range of people from different races and social classes. It has a power no other force has.

Inevitably there are going to be people who exploit that to abuse people or cause violence. It's very often used by governments as a means to militate against another government. Iran and Iraq had this terrible war in the 1980s, and religion was used by both sides to motivate their followers. But that doesn't make religion bad. That just means it's powerful. The question is all about how it's used, not what it is.

To a Western observer, some of the beliefs and taboos in these religions are bizarre in the extreme. Tell us why it's forbidden to eat lettuce, why cats are avoided by Zoroastrians, and why mustaches are imperative for some men.

The Yazidi prohibition on lettuce no one could explain. But there used to be a lot of dietary laws in ancient religion. The Pythagoreans had a rule against eating beans. No one knows why because they refused to explain. It was a sacred secret.

The Alawites in Syria believe you can be reincarnated as a plant. So some plants are taboo because they might be the reincarnations of the souls of people you know.

As for the Yazidi obsession with mustaches, some people say that the long, drooping mustache is a symbol of secrecy, and therefore it's treasured as a sign that you're worthy of being entrusted with sacred secrets.

The Zoroastrians had a thing about cats. They liked dogs very much. A house dog in Zoroastrian custom would be "buried" essentially as a human is buried-though they don't actually bury their dead. They would dress their dog ceremonially, in religious garb, and put it out for the birds to eat, which is what they do for humans. So it was a highly treasured animal, and still is. Cats, on the other hand—and I'm a cat lover myself—were regarded in the same way as ants and flies and other things that are seen as creatures endowed with an evil spirit.

Many people from these embattled religions are choosing to go into exile in the West. Why is it important that they stay in their homelands?

These religions are a part of human heritage, like the pyramids or the leaning tower of Pisa. This is important for us because it's a survival from our own past, and it helps to explain things about ourselves.

The handshake of the Yazidis, for instance, is part of the reason why we shake hands today. It's connected to the handshake of the worshippers of Mithras, which was brought to Rome in the second century and then spread across the Roman Empire. The handshake is the way we show friendship. For the Yazidis it's still a mystical symbol of unity. I give that as an example because so many of these religions connect with us in ways we might not realize.

Understandably, more and more of these minorities are deciding to leave the Middle East and come and live in the West, in Australia, Sweden, or America. The danger is that they'll lose their identity because their religions aren't designed to weather the storm of public debate and freedom. They'll need to change if they wish to survive.

One of the things we can do is help them be a bit prouder of themselves. Most of those who've left the Middle East have not emigrated by choice. They're refugees. Many are poor and have suffered terrible traumas. Showing them that their traditions and culture are valued is a great step to helping them integrate into their new homes.

One of the most poignant moments in your book comes in a supermarket in Michigan, where you hear Aramaic—the language of Christ—spoken by a girl stacking shelves. Tell us about that moment and the religious communities in Detroit most Americans don't even know exist.

Detroit is one of the few places in the world where Aramaic survives, which is a historical irony on a very large scale. Rewind: The Iraqi Christians were once one of the greatest Christian churches in the world. Ten percent perhaps of all Christians at one point belonged to it. And it had monasteries as far east as Beijing. Today its leader is in Chicago, and an increasing number of its followers are in America too.

There's a sad side to that. But there's also a wonderful epiphany, which is, of course, that these religions do survive and exist in our own midst.

I was feeling rather despondent in Detroit one day, walking round a supermarket, thinking, It looks just like every other supermarket; I don't see anything here that reminds me of Iraq. Then I heard this lady, and I thought, Gosh, that language sounds familiar, yet different. I'd learned a few words of Aramaic from my teacher in Baghdad. And I thought, Golly, that's it, it's here! And that's what it turned out to be. She was having a conversation with her coworker in fluent Aramaic.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.