Historical Atlases Rescued from the Trash Could Be a Boon to Historians

Thousands of ultra-detailed maps of the American West may finally see the light of day.

The story has become something of a legend in certain circles. Sometime in the early 1970s, geographers at California State University, Northridge (CSUN) got a tip that hundreds of historical atlases were about to be dumped in the trash up in San Francisco. They decided not to let that happen.

The chair of the department was a man named Robert Lamb. He’d learned that the Sanborn Company was closing its San Francisco office. For more than a century, Sanborn had been making incredibly detailed maps of American cities that were used by fire insurance companies to assess the risks of individual buildings—based on their building materials, how they were used, and what kind of buildings surrounded them.

Lamb knew that the Sanborn atlases would make a fantastic addition to the university’s map library and boost his department’s reputation. The hyper-detailed maps were (and still are) an unparalleled resource for geographers and historians interested in the rise of American cities and the evolving urban landscapes of the 20th century. Salvaging the San Francisco Sanborn maps would give CSUN the biggest collection of these maps in the western United States, and one of the biggest in the entire country.

Lamb quickly arranged to borrow a truck from the university, then sent a young professor and a graduate student up to San Francisco.

The Sanborn company was founded in 1866 by a surveyor named Daniel Alfred Sanborn. The rapid urbanization, industrialization, and westward expansion of the country after the Civil War had created a huge demand for maps that insurance companies could use to assess the fire risk—and set insurance premiums—for different buildings.

In the early days, most Sanborn employees had some sort of surveying or engineering background, says Chris Genovese, general manager and de facto historian for the company, which still exists today. “They would pretty much walk everything,” Genovese says, measuring building footprints and the distances between them, and taking careful notes.

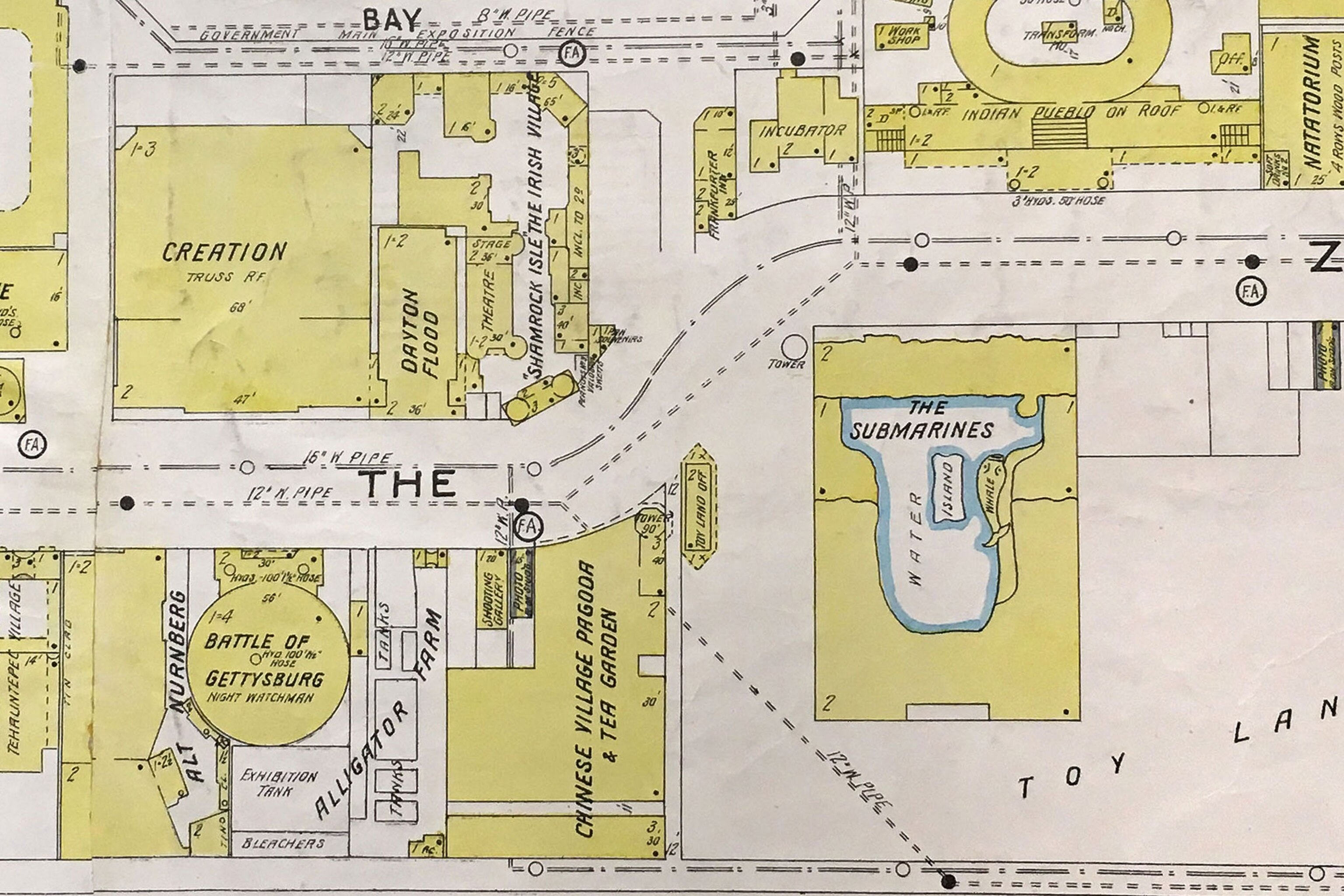

For smaller, residential buildings, the construction materials and type of roof were the most important factors in assessing fire risk, Genovese says. For larger, commercial buildings, Sanborn surveyors would go inside and make note of any flammable materials, the presence or lack of a sprinkler system, and other relevant details.

“They pretty much had carte blanche because of the power of the insurance companies,” Genovese says. (The Library of Congress, which has the largest collection of Sanborn maps, has a fascinating gallery of rail yards, factories, mines, and other turn-of-the-century industrial sites).

Sanborn surveyors and mapmakers adhered to a strict code laid out in a closely guarded company manual. They knew exactly what to look for and how to put it on the map. Though they worked anonymously, evidence of the mapmakers’ artistic flourishes can be seen in the ornate title pages like the one below.

The atlases they produced are big: Larger volumes can be eight inches thick and weigh nearly 30 pounds. An insurance company would lease a set of atlases for its area, and Sanborn employees would periodically visit to update them, pasting slips of paper onto each map to add a new building, for example, or to change the description of one. Every time an atlas was updated, Sanborn produced a bundle of slips.

“The paste slips were organized in a very specific way,” Genovese says. Each came with information about where it went on the map and had tiny marks that could be used to position it on the page.

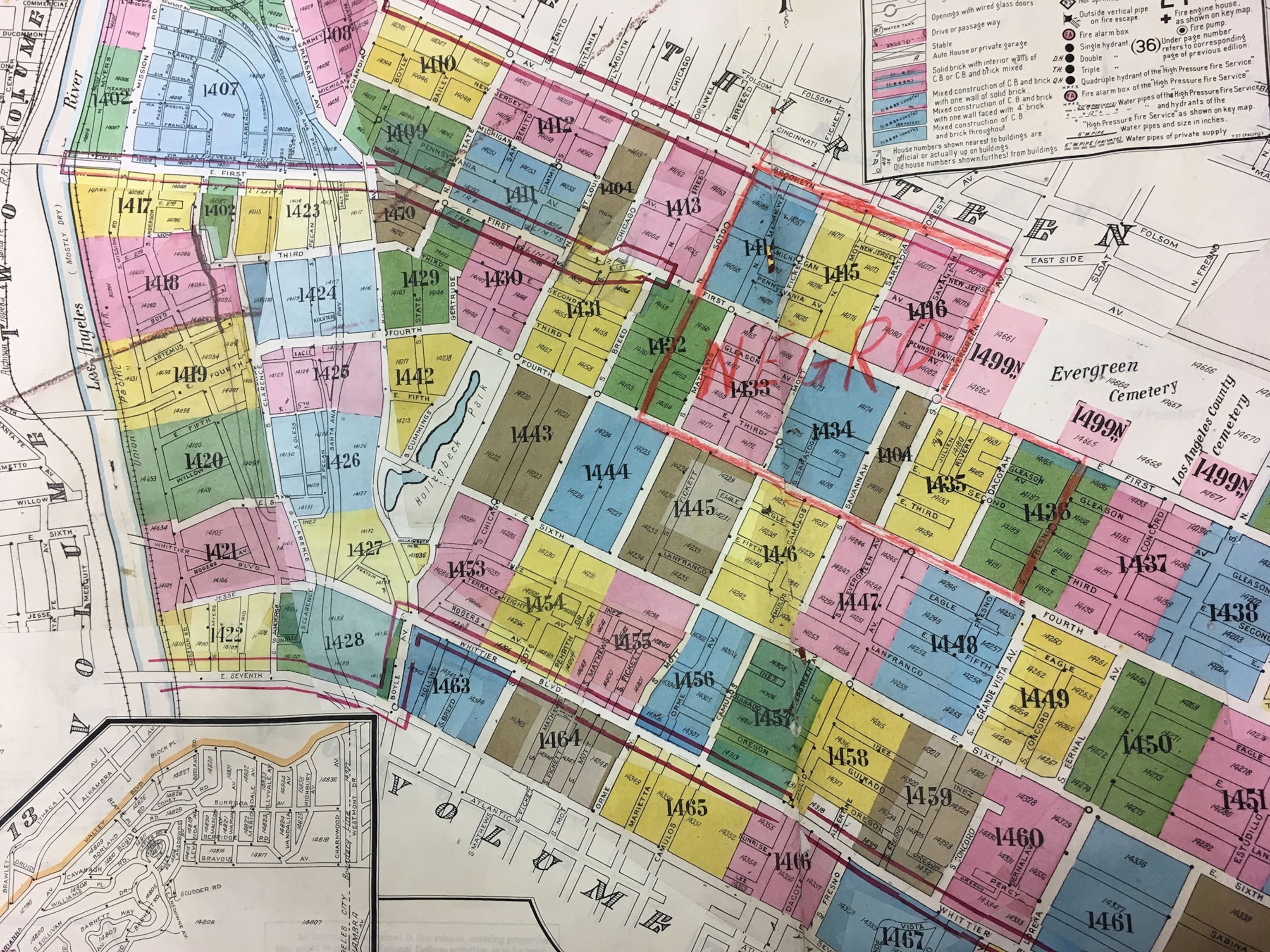

At its peak, in the 1930s, Sanborn covered more than 13,000 U.S. cities (plus some in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean). But the fire insurance map business began to falter in the 1950s, as insurers began using statistical methods to estimate risk instead of detailed evaluations of each property. Sanborn still makes fire insurance maps today, Genovese says, but the bulk of its business now comes from aerial photography and a wide range of high-tech mapping services.

The older maps are no longer used by insurance companies, but they still hold great interest for urban geographers and historians—or anyone interested in how their neighborhood has developed over time.

“They’ve got far more detail than almost any other source,” says Elliot McIntire, a retired CSUN geography professor. Because of the meticulous revisions pasted into the maps over the years, he says, “you get this whole historical sandwich of a place.”

McIntire was the young professor whom Lamb sent to rescue the atlases from a dumpster in San Francisco. The details are hazy now—this happened almost 50 years ago, after all—but McIntire remembers loading hundreds of heavy atlases into an open stake bed truck. “We stacked them carefully and hoped it didn’t rain,” he says.

According to most tellings of the story, they got the truck loaded just in time. As they were pulling out, a truck from UC Berkeley (or, some say, UCLA) pulled up, hoping to score the atlases for that school. “I don’t remember that,” says McIntire, “but it’s entirely possible.”

He does recall getting queries from city planners interested in using the collection, as well as a far more unusual request from someone who wanted to use the maps to find abandoned outhouses. In the 1800s, people apparently tossed empty bottles into their outhouses, and over the years the bottles turned attractive shades of blue and green. “There was a market for this 19th-century glass,” McIntire says. “It was a pretty good collector’s item.”

The current map librarian at CSUN, Christopher Salvano, is working to make the Sanborn maps more accessible to scholars and the public. He’s started digitizing the index maps for Los Angeles County and is collaborating with map librarians at Stanford and several campuses of the University of California to digitize Sanborn maps of California and make them available online for researchers. The project is just getting off the ground, Salvano says. “The overarching goal is to unhide these collections,” he says.