Yurts, Yogis, and Cowboys: Skiing Away From the Modern World

It’s still dark, but I can hear him wrestling with the fire. I struggle, halfway between dreams and consciousness. It’s a late night, spent envisioning the wolf outside sniffing our yurt. We haven’t seen any wolves or any of their traces, but I can’t help my imagination—at night, it finds the wolf.

In the morning we’re always awakened by Kas, the Kyrgyzstan local who’s teamed up with 40 Tribes, a yurt-skiing operation founded by Colorado guide Ryan Koupal. Kas sneaks in just before the sun shines through the ceiling of our yurt, which proudly boasts the same design as the Kyrgyzstan flag, and builds a new fire. He’s meticulous and efficient, and the night chill always dissipates quickly. I listen to the girls chatting without any real consciousness of what they’re saying and only wake up when I sense they’re drinking coffee, also made and brought in by Kas.

Every morning during our weeklong escapade into the Tien Shan remoteness begins like this: slow and steady in a blissful way that eases the pain of traveling from around the world to get here. Mountain guide Kitt Redhead and photographer Zoya Lynch have flown in from Vancouver, our yogi guru Ally Bogard from her new home in New York City, and I from my home base in Austria. The trip manifested for me via an invitation from Zoya. I didn’t know the other girls beforehand and never expected the trip would bring me sisters. Coffee in bed and sisters—these days that easily qualifies as a trip of a lifetime.

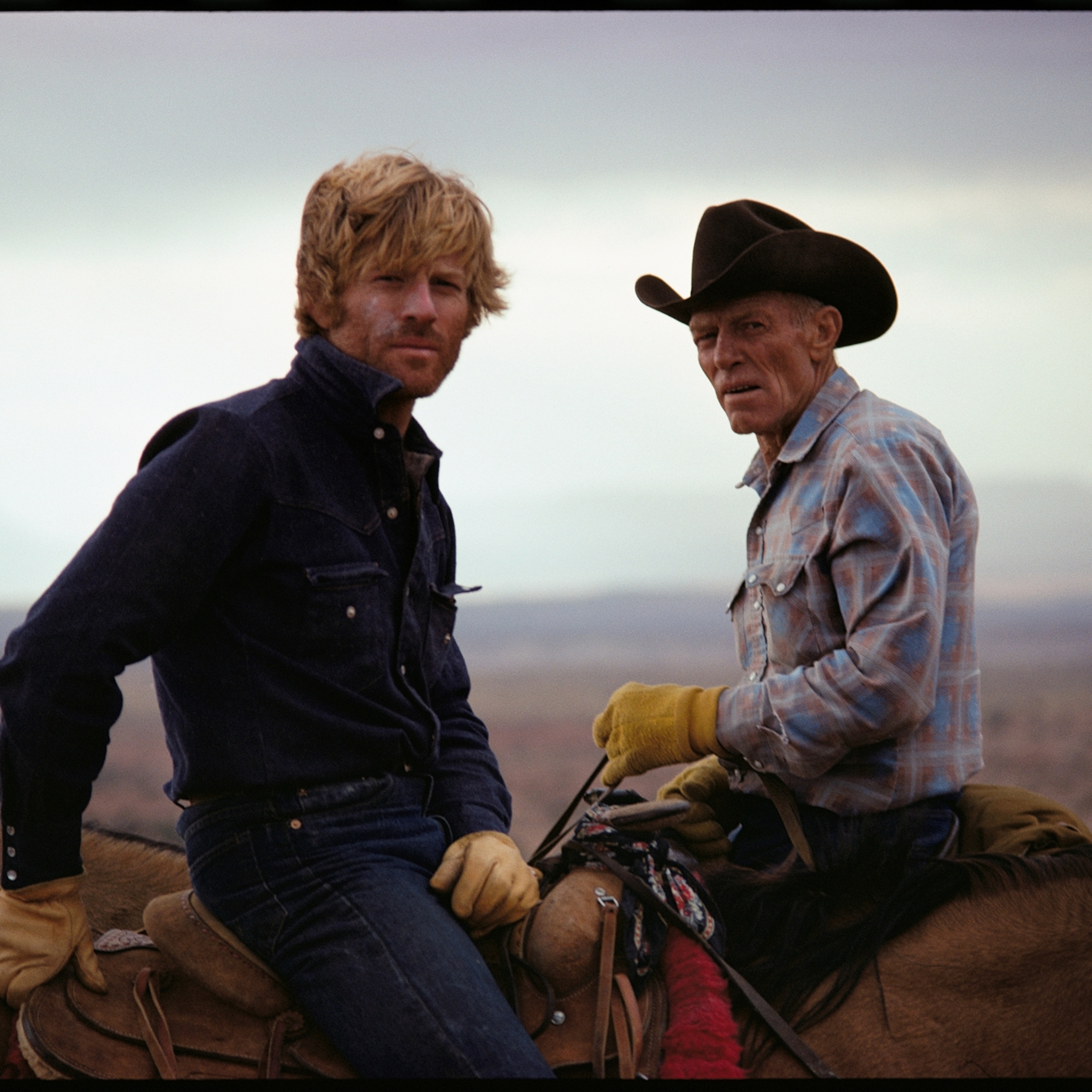

After coffee we venture to the meal yurt, where we share breakfast in a bowl—pancakes, eggs, potatoes. It always all goes into a bowl. At our little table, we give many thanks to the resident chef, Norbek, while Kitt and the lead guide at 40 Tribes, Ptor Spriecknicks, share ideas for the day. Ptor, an absolute legend and as-keen-as-it-gets mountain man, always wants to ski the glory lines. Hyper-intuitive Kitt, a charging skier and mom, gently and consciously pulls the Ptor reins in slightly (mostly at my request) and we usually see both influences emerge in our day plan. For me, skiing in Kyrgyzstan is like jumping on a bucking bronco—unpredictable in every element. Ptor is a perfectly trained cowboy, and the rest of us are just learning.

Ryan’s pre-trip advice was determined to prepare us for this place, and after traveling and skiing around the world I wondered how the mountains of Kyrgyzstan could be that much different. But as I made my first turn, I understood exactly how unique it is here. I’ve never skied snow like it, and suddenly Ryan’s request for skis only over 115mm underfoot made sense. Who knew powder skis were perfect for quicksand?

At an elevation of nearly 8,700 feet, the 40 Tribes yurts are located above the Issyk-Kul valley in the northeast. The Tien Shan mountains cover over 80 percent of the country, and the Eastern Terskey Ala-Too sub-range—with the second largest alpine lake in the world nearby providing moisture, subzero temperatures, and a desert climate that still maintains consistent snowfall—experiences a unique type of snow. The snow that falls in these high-altitude desert peaks is cold and exceptionally dry.

When we arrive, much of what we can access is cold and sugary. If you slow down at all while skiing, you stop and sink—only it’s not like sinking into a glorious powder turn. In this snow, there’s no bottom, and sinking means stopping. I know how ridiculous this sounds; I didn’t believe it either until my thighs were burning from sitting so hard in the back of my boots, my skis so close together that I might as well have been monoskiing, so I could keep myself from taking the plunge into the Kyrgyzstan quicksand on our first run. If you push into Kyrgyzstan powder, it doesn’t push back. We learn this as we ski everyday, accessing long, beautiful runs that start from around 13,000 feet and end back at the yurts.

Although it’s challenging to learn the best way to approach the conditions, we move with ease as a group, skiing a run named after Zoya’s sister, pro skier Izzy Lynch, and one called Yurtzee, a reference to the local favorite après pastime, Yahtzee. Skiing here is a fast, light-footed dance, and in many ways the process of learning to tread lightly is a necessary one—in all aspects of our lives. These mountains are just another piece of that lesson.

It isn’t really a trip of pushing. In prior years I’d become so accustomed to only wanting to go on ski trips with people who would motivate me way outside of my comfort zone and would only feel like the trip had given me something if boundaries were left far in the distance. Now, filled with patience and prioritizing a safe return home to Austria, I want to tiptoe through a dream of peace, safety, and gentleness, and because of that, my companions are as good as it gets.

Every evening before dinner our yogi wise woman, Ally, leads us through a revolutionary yoga session. On our beautiful hand-woven Afghans, amid a raging Kas-stoked fire, we sweat ourselves into a hunger for a dinner of meat and potatoes and homemade hot sauce. After one week, the girls, each conscious of not eating too much red meat, have consumed preposterous amounts of potatoes. Even while offering the most satiating home-cooked meals by Norbek, Kyrgyzstan pushes even the most relaxed vegetarians.

On the last day we finally go for a line that Ptor has been calling out since our arrival: the Shrine. It’s near Wolf Ridge and takes us all day to access. Ptor drops the blind roll at the top first, proclaiming as he always does, “Ski it like you mean it,” and stops at a safety spot on the bench below. We regroup before descending the glorious remainder of the line as it falls away into the trees and valley below.

After a week of skiing Kyrgy snow, we’ve adapted, and the flow through our skis and into our bodies is starting to return. We watch Ptor fly over another blind roll and know he’s hooting and hollering through the trees. I drop second and, when I catch something out of the corner of my eye at the steep roll in the terrain, I assume it’s a rock to avoid. At the bottom I navigate a small slough that Ptor had set off and cruise to the safe zone to find our cowboy smiling as big as it gets. His spirit is on fire, and before me I see a man who will never turn his back on skiing.

- National Geographic Expeditions

“Did you see the shrine?” he asks with both skiing excitement and a little trepidation. I’d made my caution about this place and the mountains very apparent since our first day together.

The rock? The small avalanche? I wonder what he’d wanted me to see.

“The shrine! I didn’t want to tell you before we skied, but the run is called the Shrine because a man died there,” he says. “He was from a nearby village and walked up here barefoot to die during the summer. Now there’s a monument for his spirit in the middle of the run.”

I’m thankful that Ptor hadn’t told me before we skied, because the run would have felt more like an intrusion than the best skiing I had on the trip (since I was finally in a place where I felt the mountains welcoming us). Now that he’s told me, I wonder if the wolf I’ve been seeing in my dreams is the man who walks these mountains now for eternity.

We’re so far away from anything familiar that every thought, idea, and instinct is possible. There’s no reality to tell us any differently, and that—beyond the snow, yurt life, people, and family meals—is the magic of Kyrgyzstan. It’s a place to go without the influence of the world and to feel exactly where you are in this life and where you want to go. A zone in the world where friends feel like family and one can listen to their dreams and escape from the intense pushing of the modern world we’ve all become so accustomed to. As it turns out Kyrgyzstan isn’t just for cowboys but for any type of spirit: wolves, locals, yogis, and so many more.