Epic Eel Migration Mapped for the First Time

Scientists use satellite tags to track American eels to an open ocean spawning area—a first for science.

Scientists know that American eels spend most of their adult lives inland or close to the shore, because for thousands of years, that’s where people have caught them. And we know the animals spawn in the open ocean, because that’s where we find their tiny, transparent larvae. But despite decades of searching, no adult American eel (Anguilla rostrata) has ever been spotted migrating across the hundreds of miles of ocean between the animals’ adult haunts and their ancestral spawning areas.

That is, until now.

A team of Canadian scientists used satellite tags to track an adult female eel from the coast of Nova Scotia to the northern limits of the Sargasso Sea in the middle of the North Atlantic—a journey of more than 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers). The team published their results Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

“It’s pretty exciting,” says Julian Dodson, a biologist at Laval University in Quebec City and coauthor of the new study. “We’re beginning to catch a glimpse of what’s going on for the first time.”

American eel numbers have plummeted in the last few decades, earning the animals an endangered classification from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. All the more reason, says Dodson, for us to learn about eel reproduction while we can.

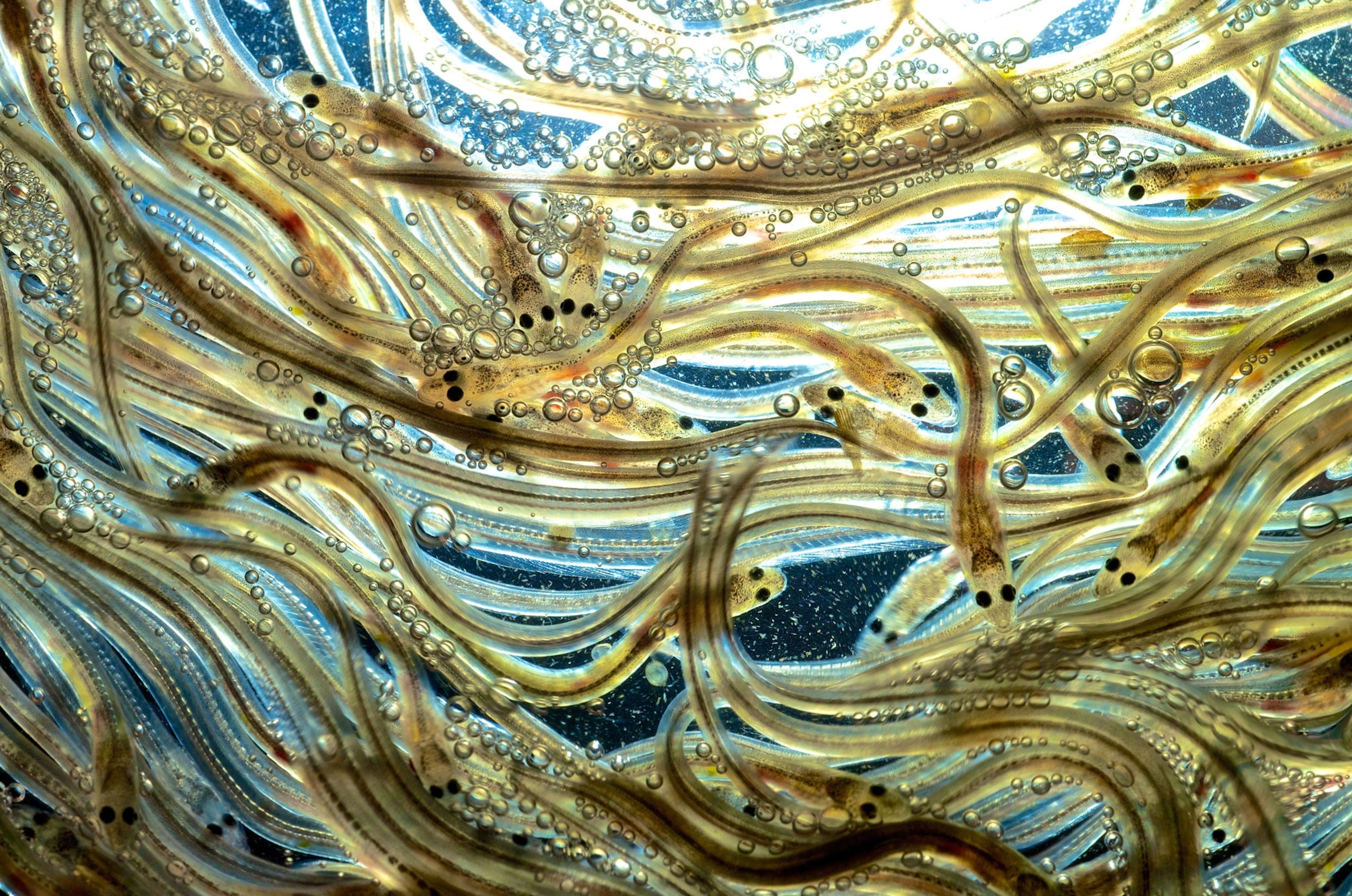

Slippery as an Eel

Adult eels, also called silver eels, spend most of their lives in freshwater habitats such as the Great Lakes and in brackish estuaries, the transition zones between rivers and open sea. The animals are nocturnal, haunting the roots and rocks of riverbeds from the Gulf of Mexico to the St. Lawrence River in Canada. They can live to be twenty years or more before returning to the open ocean to spawn. But it is their final act—the animals die soon after.

At least, that’s what scientists think happens. But American eels have proven exceptionally difficult to keep tabs on. The satellite tags researchers use to track eels’ movements can come off prematurely as the fish slither against mud and rocks. They can also malfunction and pop off before an animal reaches its breeding grounds.

And though American eels can grow to nearly four feet (1.2 meters) long, they are a tasty snack for many open ocean predators. Previous studies that have used temperature and depth measurements from the eels’ satellite tags show that they sometimes wind up in the bellies of the sharks that frequent the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Dodson says. Those findings led Dodson’s team to start releasing their tagged eels in different locations, further from the sharks’ hunting grounds. “We didn’t want to keep feeding our rather expensive satellite tags to porbeagle sharks,” says Dodson.

Another Piece of the Puzzle

Finally, after years of trying, the researchers recently captured data from a female eel—eel No. 28—that made it from Nova Scotia to the northern edge of the Sargasso Sea.

According to her tag, No. 28 made the journey by swimming 30 miles (49 kilometers) a day. Depth measurements showed that—probably to avoid predators—she dove to deeper waters while the sun was up, sometimes reaching depths of more than 2,000 feet (699 meters). Such deep dives may help explain why no one has so far sighted the eels en route to their spawning grounds.

After 45 days at sea, No. 28’s tag popped off and started beaming all of its GPS coordinates, depth, water temperature and salinity, and other data up to a satellite. Dodson says this could be an example of premature detachment, since the tags were designed to stay attached for up to five months. Or perhaps it indicates that No. 28 was attacked by a predator.

Even though No. 28’s tag detached before she could reach the heart of the breeding grounds, American eel expert Steven Shepard praised the researchers for succeeding where similar studies had been stymied by premature tag loss or high mortality.

“This study advances the state of knowledge of silver eel migration at sea,” says Shepard, a biologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and co-author of the agency’s recent status review for the species.