Why Smuggling of This Ocean Creature May Skyrocket

A proposed law would bar wildlife authorities from monitoring exports of sea cucumbers.

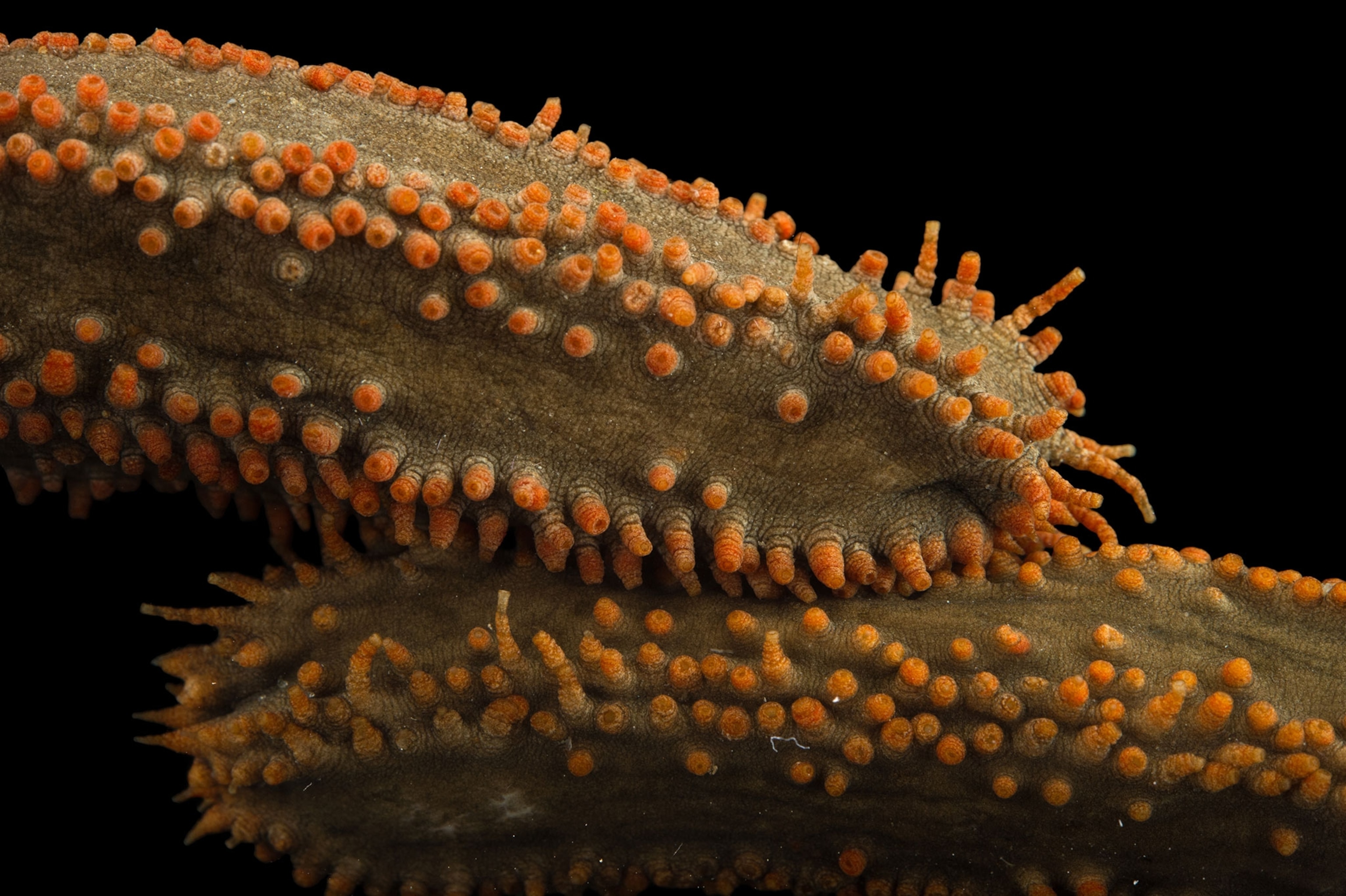

JONESPORT, MAINE — It’s a bright, crisp, windy afternoon at the marina in one of eastern Maine’s tiny coastal fishing towns. On the deck of his trawler, Adam Stanwood—a barrel-chested, apple-cheeked fisherman in his 40s—uncovers a black plastic tray about two-and-a-half feet by one-and-a-half. It’s full of squirming gray-brown sea cucumbers. Maine fishermen call them “pickles,” and they do indeed resemble inflated kosher dills adorned with a spray of tentacles on one end.

Stanwood has filled only three trays since he sailed out at five this morning—a disappointing catch. A good day’s work, he says, is 30 to 40 trays. But that’s nothing compared to what it was like in the 1990s when he could get 21 trays out of a single tow of his drag net.

It was then that the Asian market for edible sea cucumbers hit Maine’s coast. In the absence of regulations, landings increased from one to three million pounds in the mid-1990s to more than nine million in 2000.

Worried about overfishing, in 2004 the state imposed a moratorium on new fishing licenses. This year Stanwood is one of only six Maine fishermen with active sea cucumber licenses. Cucumbers are a side business for him, he says—scallops are his mainstay.

But the sea cucumber fishery never recovered, and Stanwood says he wishes state regulators had stepped in sooner with harvest limits, though he admits he didn’t advocate for regulations himself. “Hindsight kinda sucks sometimes,” he says.

Along with sea urchins and starfish, sea cucumbers belong to a group called echinoderms. Sea cucumbers are critical to marine ecosystems all over the world, cleaning the sea floor of small particles and waste materials and turning them into nutrients that other creatures can use, much like earthworms on land. They make marine ecosystems more productive, and their alkaline defecations may even buffer coral reefs against the erosive effects of ocean acidification.

Yet these beneficial creatures are in trouble, not only in Maine but globally. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says 66 species are overexploited worldwide.They’re considered a culinary delicacy in Chinese cuisine, along the lines of shark fin soup.

Demand from China’s growing wealthy class has given rise to an international sourcing network that drops into one coastal community after another, often depleting sea cucumber populations before authorities have a chance to react. And while global outrage over the slaughter of sharks for soup may have helped to level-off demand, no such outcry has been raised on behalf of the humble sea cucumber.

With the high prices they command—up to $500 or more per kilogram when dried, according to authorities—sea cucumbers are becoming the hot new black-market commodity.

In Southern California, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s law enforcement branch is struggling to shut down an illicit trade from south of the border. In the latest development, on May 17 charges were filed in San Diego against a father-son team and their Arizona-based company, Blessing Seafood, Inc., for allegedly smuggling more than $17.5 million in sea cucumbers illegally caught off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula to Asian markets via the U.S.

Erin Dean, resident agent in charge of the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Southern California region, says illegal sea cucumbers from Mexico are involved in as many as half the open wildlife investigations there. “We’re seeing sea cucumbers that are being concealed inside vehicles, hidden inside compartments of vehicles, pedestrians carrying across small quantities of sea cucumbers—that we believe are being consolidated into larger shipments on the U.S. side and shipped out to Asia,” she says.

A BILL TO PREVENT INSPECTIONS

On the same day charges were filed against Blessing Seafood and its owners, Maine Congresswoman Chellie Pingree introduced a bill that would prevent the Fish and Wildlife Service from monitoring exports of sea cucumbers, as well as their round, spiky cousins the sea urchins, for illegal activity. The bipartisan bill—H.R. 2504, entitled “To ensure fair treatment in licensing requirements for the export of certain echinoderms”—is sponsored by all four of Maine’s Congressional representatives—Democrat Pingree and Republican Bruce Poliquin in the House and Independent Angus King and Republican Susan Collins in the Senate.

The legislation has its origins in a bill first introduced by Pingree in the previous Congress. That bill would have exempted both imports and exports of sea urchins and sea cucumbers from Fish and Wildlife Service inspections.

Under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, any wildlife or wildlife product shipped into or out of the U.S. for commercial sale must be declared to the Service, which is tasked with monitoring international trade in wildlife, making sure it’s legal, and collecting data on how much wildlife is being commercially shipped into and out of the country.

Some kinds of shellfish and fishery products, including lobsters and oysters, are exempt from these inspections. (The legislative history indicates that the exemption, which initially covered only imports, was intended to prevent fish caught by American fishermen on the high seas for the domestic market from being considered a foreign “import” requiring declarations and inspections like wildlife from another country.)

Pingree and other proponents argue that it’s unfair that Maine’s sea urchins and sea cucumbers must be inspected when lobsters and oysters aren’t.

The sea cucumbers and urchins harvested in Maine are certainly destined for someone’s plate. Sea urchins are collected for their roe—technically, gonads—which you’ll find on sushi menus as uni. The state’s one commercially important sea cucumber species, the orange-footed sea cucumber, is cut up, its internal muscles frozen, and the body wall and tentacles dried to be reconstituted in soups and stews.

But other aquatic wildlife collected in the U.S. and exported for food are subject to Fish and Wildlife Service inspections, and those inspections have helped the agency uncover illegal trade, such as the widespread smuggling of baby eels in the Northeast. Conservationists fear a slippery slope. If it’s sea cucumbers and sea urchins today, why not octopus, turtles, and alligators tomorrow?

In a prepared statement presented at a legislative hearing for last year’s version of the bill, William Woody, the Service’s chief of law enforcement, noted that the seafood exemption “is purposefully narrow to discourage smuggling and illegal trade.” Adding sea cucumbers and urchins to the exemption, he said, would limit “the Service’s ability to…detect and deter unsustainable, illegal trade,” pointing to the “highly profitable black market for transshipment of sea cucumbers through the United States” that the Fish and Wildlife Service had already uncovered.

Nevertheless, last year’s bill unanimously passed in the House under suspension of rules, a motion normally applied to uncontroversial legislation, such as naming post offices.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has declined to comment directly on the pending legislation, but Erin Dean says that inspections of sea cucumbers are crucial for putting together the cases she and her team have been working on.

“Wildlife inspectors are the front-line officers responsible for identifying protected wildlife, examining documents that are presented with the shipments, and detecting if there’s a problem,” she says. “So their role is absolutely critical in stopping illegal trade of wildlife coming in and out of our country.”

That applies to exports as much as imports, Dean says. She notes that agents have seen a marked rise in illegal wildlife exported from the U.S. “Back when I first started as an agent in 2001 the majority of our cases were illegal imports—smuggling inbound. Now we’re seeing a significant shift in wildlife being shipped out of the U.S. In this case, obviously, sea cucumbers, but also live turtles,” and, she adds, other wildlife being smuggled out to Asia. (Also read: Will America's Turtles Be Eaten Into Extinction?)

Conservation organizations, alarmed by the bill’s easy passage, lobbied against the legislation. In a letter 21 groups warned the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works that barring the Fish and Wildlife Service from inspecting sea urchins and sea cucumbers would “create loopholes for wildlife trafficking, undermine law enforcement’s efforts to intercept illegal trade in marine wildlife,” and “make it nearly impossible for the Service to track these highly vulnerable marine species.”

Pingree’s original bill was amended several times, but it died in last year’s legislative session before it could be reconciled with the much more moderate Senate version, which merely required the director of the Fish and Wildlife Service to propose an expedited export process for sea urchins and sea cucumbers.”

Pingree’s reintroduced bill forces the director of the Fish and Wildlife Service to change the Code of Federal Regulations to exempt sea urchins and sea cucumbers.

ARBITRARY NEW REGULATIONS?

Congresswoman Pingree, whose past voting record falls firmly on the side of environmental and wildlife protections, is an unlikely champion for an exemption to echinoderm inspections. As Andrew Colvin, her deputy director of communications, wrote in an email in December, “Congresswoman Pingree has the utmost respect for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and its important work. She is a regular advocate for the agency on the Appropriations Committee.”

“That said,” he added, “this is not the first time she has stood up against federal regulations when they have unnecessarily or unintentionally hurt Maine’s fishing industry or the thousands of jobs it supports.”

Pingree and other proponents of the bill accuse the Service of only recently requiring that sea urchins and sea cucumbers be inspected, suggesting that there was some arbitrary and capricious change in policy or enforcement.

At last year’s hearing, and in press releases, Pingree says she was contacted by the Maine Sea Urchin and Sea Cucumber Association “in late 2014 after federal officials started requiring inspections of urchins entering and leaving the United States.”

Atsushi Tamaki, president of the association, and owner of I.S.F. Trading (I.S.F. stands for International Seafood Trading), Maine’s first and oldest sea urchin processor, made a similar claim at the hearing.

But documents obtained by National Geographic through a Freedom of Information Act request show that at least three of Maine’s sea urchin processors, including I.S.F. Trading, had Fish and Wildlife Service import/export licenses for sea urchins and sea cucumbers in 2012, and before that too.

In addition, the Service’s law enforcement records, shared by the Washington, D.C.-based Animal Welfare Institute, show that imports and exports of both animals were being declared to the agency and cleared by wildlife inspectors in 2012 and previously.

The bill’s proponents also claim that expensive shipments of uni have spoiled while awaiting inspection in hot warehouses—although so far no evidence of this has been presented.

In January Victoria Bonney, Pingree’s communications director, responding by email to National Geographic’s inquiry about evidence of spoilage, implied that they hadn’t seen any.

“Our office went by the testimony of multiple processors who told us in repeated meetings that their product would at times wait several days for inspection in warehouses that were not temperature controlled. Later, we became involved in a case where a shipment would have sat in a warehouse for three days because inspectors left early for a long weekend. Since it’s well known that urchins are a very perishable product, there's good reason to believe that extra time in a hot warehouse puts the product at great risk of spoiling, either then or en route to someone’s plate in Asia.”

Like its sea cucumber fishery, Maine’s sea urchin fishery is a mere shell of its former self. Just two million pounds were landed in 2016, compared to more than 41 million pounds at the fishery’s peak in 1993, according to the Maine Department of Marine Resources. The five sea urchin processors registered in Maine import much of their urchin shipments live from Canada and South America for processing and export.

Generally that’s legal, but in April 2016, I.S.F. Trading pleaded guilty to illegally importing 48,000 pounds of live sea urchins into the U.S. from Canada. Atsushi Tamaki had purchased the urchins from a company in Canada that had no license to export them, in violation of Canada’s food safety laws, and had mislabeled the urchins with the name of a licensed Canadian company, according to court records. (The Fish and Wildlife Service was not involved in this investigation.)

News that I.S.F. Trading had admitted to smuggling sea urchins had circulated in Maine more than a week before the House unanimously passed last year’s version of the bill in September.

Pingree later declined a request to discuss I.S.F. Trading’s guilty plea, among other things.

As of this writing, the new bill is in committee in both the House and the Senate.

The proposed exemption for sea cucumbers and sea urchins is one of dozens of attempts to roll back protections for at-risk species. (Also read: Inside the Effort to Kill Protections for Endangered Animals).

Jamie Pang, with the Center for Biological Diversity, was among those who tried to stop the echinoderm exemption last year. She calls the bill’s reintroduction “disappointing and shameful.” In an email she said, “Emboldened by Trump, the industry has ramped up lobbying efforts on Congress, and even moderate politicians like Chellie Pingree and Angus King are acceding to their requests without even considering the effects on conservation or the weakening of the Endangered Species Act.”

Maraya Cornell is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles. Follow her on Twitter.