The Secret History of the Women Who Got Us Beyond the Moon

They had "to look like a girl, act like a lady, think like a man, and work like a dog"—and do the hard math that got rockets into space.

Q: What do Tim Berners Lee, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, Joel Oppenheimer, Linus Torvalds—the list could go on—all have in common?

A: They are all men.

Sure, there are influential women in technology and science but the numbers are few. The same is true of space exploration. All the world knows the name Buzz Aldrin. How many of us have heard of Bonnie Dunbar or Joan Higginbotham?

But “man” would never have made it to the moon without the work of a group of brilliant and tenacious female mathematicians at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, argues Nathalia Holt in Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, From Missiles to the Moon to Mars.

Speaking from her home in Boston, Holt explains how the lab’s first “computers” were women; why, despite their example, the number of women working in technology today is falling; and how the Voyager program is, literally, carrying these women’s legacies to the stars.

It sounds like Elton John needs to change the lyrics to his song “Rocket Man.” Who are the “rocket girls?"

The rocket girls started out as a group of “computers” at the Jet Propulsion Lab. Before all of the digital devices we have today, you actually needed humans to do calculations. They were called computers because they were responsible for all the mathematics in the lab. What was surprising to me was that the rocket girls had these long careers in the lab. They went from being these early computers to becoming the lab’s first computer programmers and engineers and, as a result, have had an incredible influence on NASA. They touched just about every mission you can think of.

Why have we never heard of them?

This is quite sad, really. When I first started researching the book, I found that the archives had these lovely pictures of the women who worked at JPL in the 1950s. But there were very few names and no contact information. So it took me quite a while to track them down and learn about their stories.

Unfortunately, this is the case with many female scientists. Many brilliant male scientists have their stories lost to history. But it seems to be most frequently women whose stories are left out.

What drew you to this story, Nathalia?

I came across this story in a very unusual way. In 2010, my husband and I were expecting our first child and we were having a difficult time coming up with names. My husband suggested Eleanor Francis. I wasn’t sure, so I did what parents do these days: I Googled the name. What popped up was this woman named Eleanor Francis Helin, with a lovely picture of her accepting an award at NASA in the 1960s. I was stunned by this picture because I had no idea that women worked at NASA at this time, much less as scientists. So I was drawn to find out who she was—and then learned she wasn’t alone.

I love the job description "computers urgently needed to apply." Tell us the secret of applying to be a computer—and who these computers were.

[Laughs] These advertisements were wonderful. Many of the women that saw them didn’t know exactly what a computer was, but they were very skilled at math and there weren’t many career opportunities for women in science at that time. The options were generally teacher, nurse, or secretary. So when these women had an opportunity to get a job at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory it was very exciting.

It ended up being an all-woman group because of a woman named Macie Roberts. She was made supervisor of the computers in 1962 and decided it would be too difficult to hire men. She felt they would undermine the cohesive nature of her group. She also worried that, at that time, it would be difficult for a man to have a woman as a boss.

[Laughs] You couldn’t do that today!

No, it would be a lawsuit. [Laughs] But because Macie Roberts started that culture so early, it kept on over the decades. When other women became supervisors, they kept this attitude of hiring women. This is really clear with Helen Ling, who had had a very long career at JPL. She brought in many women who wanted to be engineers but didn’t have the necessary degrees. She encouraged them to go to night school and ends up filling the laboratory with women engineers.

Janez Lawson saw one of those signs and knew that “no degree necessary was a secret code for women can apply.” Tell us about Janez.

She has an incredible story. She’s a brilliant, young African-American woman who received her degree in chemical engineering from UCLA. She knew it would be almost impossible to get a job as an engineer, so she applied to JPL after seeing this ad, realizing this was an opportunity to get her foot in the door. It was a big deal when she was hired. She was the first African American working in a technical position in the lab. And she excelled there. She is one of only two people sent to a special IBM training school, ends up being a part of many important missions and goes on to become a chemical engineer and have a brilliant career later in life.

There is now a film Hidden Figures coming out about Katherine Johnson, the African-American woman who calculated the trajectory of our first trip to the moon. You don’t write about her though. Can you tell us why?

I’m very excited about Hidden Figures. But I chose to concentrate on the women at JPL because what they had there was very special. At many NASA centers, people that worked those computers ended up having very short careers because, once IBM came in, many of their jobs were eliminated. This didn’t happen at JPL. You have this group of women who ended up having 40- and 50-year careers. One of them, Sue Finley, actually still works at the lab today and is NASA’s longest-serving woman. It had a lot to do with the culture at JPL and, of course, these amazing women.

Did you personally interview these women? What were they like?

I did interview them and feel fortunate to have spent so much time with them. They are very warm, kind people, who are excited to talk about all of the science they were part of. In 2013 I organized a reunion and had women coming from all over the U.S. to participate. It’s a sad fact that this group hasn’t gotten the recognition they deserve from the laboratory they worked at. So it was a really special event. To be at the lab with them, touring around, listening to their memories, meant the world to me.

Macie Roberts said of the rocket girls’ jobs: “You have to look like a girl, act like a lady, think like a man, and work like a dog.” Tell us how she created a hiring sisterhood that would continue through the decades.

That quote sums up so much of what the early days at JPL were like. There were sexist attitudes then, as there is sexism in science now. But because they were this close-knit group of women they were able to lean on each other and accomplish something very unusual. In 1960, only 25 percent of mothers worked outside the home. What we see with these women is that they supported one another. After one of the women had a baby, Helen Ling, the supervisor after Macie Roberts, would call her up and ask her to come back to work. They created their own culture in the lab and this led to some amazing developments in exploration.

Who was Cora and why did the women consider her one of their own?

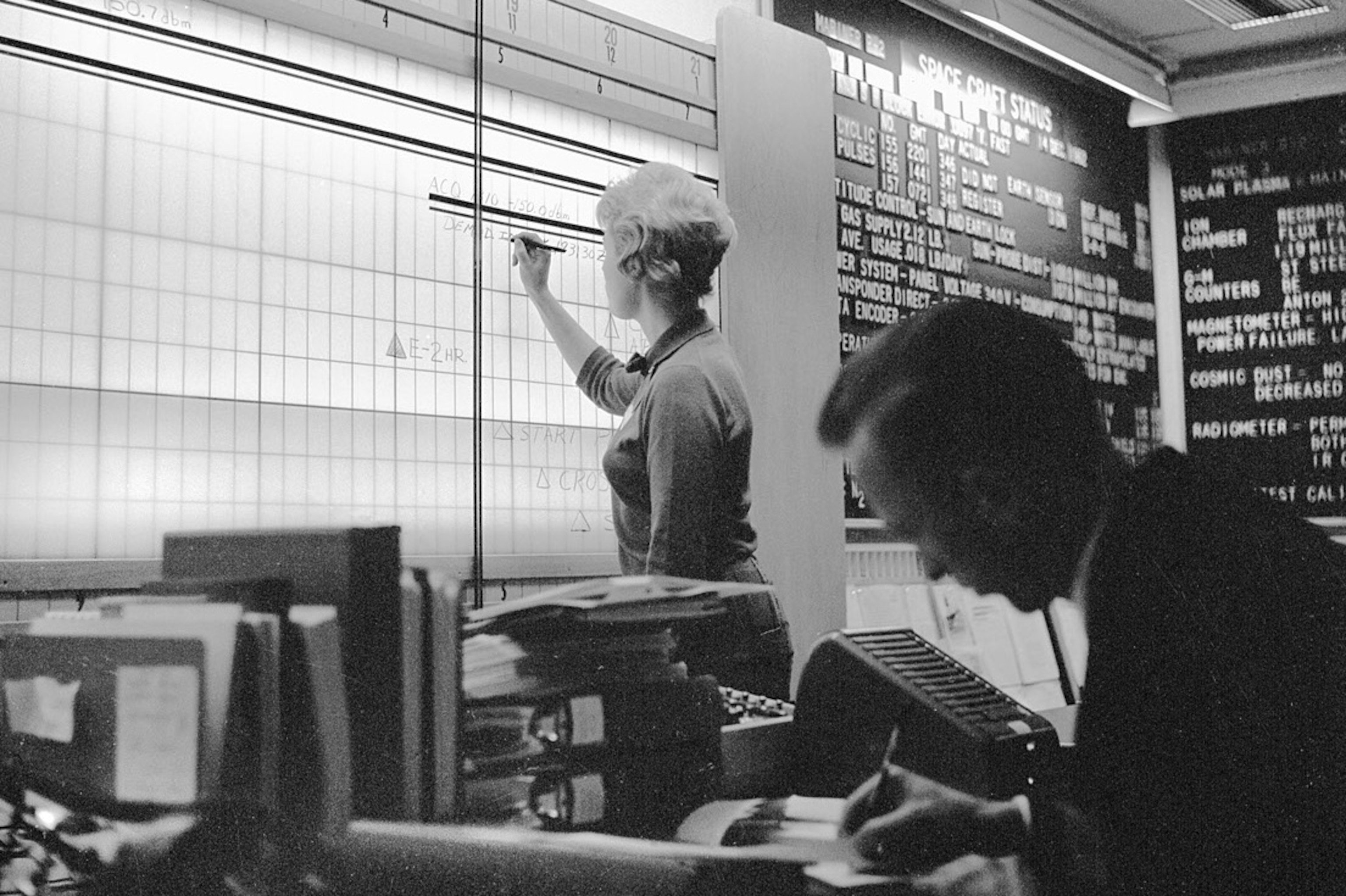

Most of the engineers at that time were men and they were suspicious of computers, because they were not very reliable in that era. They tended to overheat. Even in the 1960s, calculations for most NASA missions were done by hand, using paper and pencil. But because of the men’s distrust of computers, these women ended up being the first programmers in the lab and developed this special relationship with one of the computers.

Cora was an IBM 1620. She had her own little alcove off to the side of the women’s offices. On the door were the words “core storage.” The women decide this would not do, so they renamed her “Cora”—and put a list of all their names on the door.

Long before anyone was burning bras or even knew the term women’s lib, these engineers were balancing career, family, and children. How did they do it?

They were able to balance these lives due to many factors. Some were institutional policies at the lab, like being able to work flexible hours. Even during missions, when they would often have to work all night, they were able to adjust their schedules, by coming in early or staying late, and this made a big difference to their ability to balance their lives. At other NASA centers, people who worked as computers often had to work eight-hour days with very set breaks. In some places they couldn’t even talk to each other. They had to work in silence! This didn’t happen at JPL. But there were still issues. At the time, it wasn’t always easy for spouses to cope with their wives having important careers. Others did an amazing job of being there for their wives.

How did the rocket girls change the culture at NASA—and how can they inspire today’s girls and young women?

Having this all-female team made a big difference. This is also rooted in research that we have now. There is more sexism in industries that are typically male-dominated and this can be alleviated by having more gender balance. This group of women at JPL changed the culture because they were included in so much of the lab’s life. Even social events, like beauty contests, which seem ridiculous by today’s standards, had a positive influence on their careers because they ended up becoming very close with their male colleagues. This meant they were included as co-authors on publications, at a time when it was not common for women to be included in this way.

Today, we’re seeing a very sad drop of women in technology. In 1984, 37 percent of degrees in computer science were awarded to women. Today, that number has plummeted to 18 percent. There are many different reasons. Some of it can be attributed to the sexism pervasive in this field. So having these women as role models is important for women in science today. If the rocket girls could do it in 1955, women can surely do it today!

Tell us how Voyager is carrying these women’s legacies to the stars.

Voyager is the pinnacle of these women’s careers. The original Voyager mission was curtailed due to budget cuts, so these women worked in secret, behind closed doors, trying to figure out the best trajectory for the Voyagers. If they hadn’t done so, the mission would have ended at Saturn instead of exploring the entire solar system. Their legacy is, quite literally, inside those memory banks. And Voyager is now carrying that legacy to the stars.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.