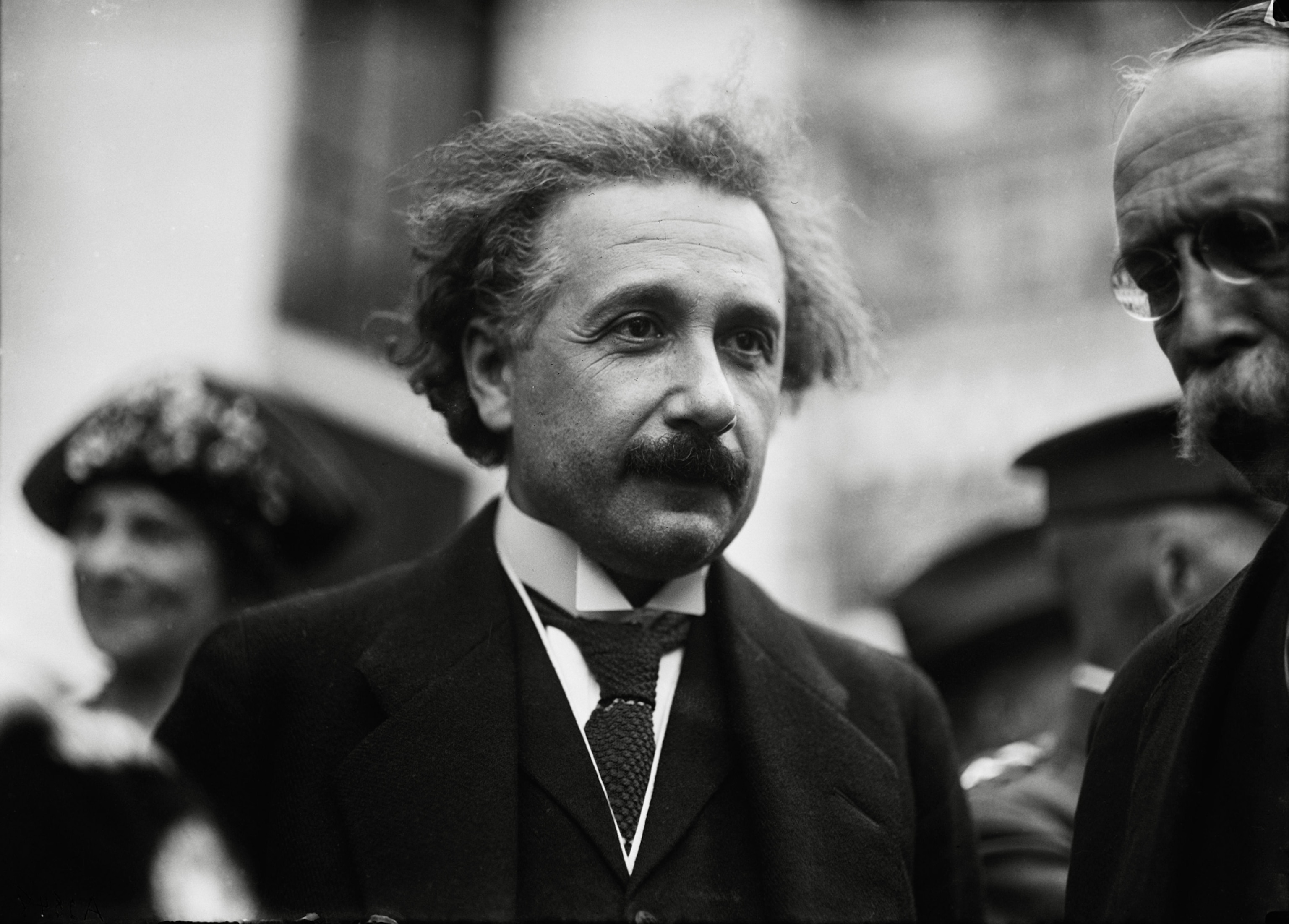

Facts about Albert Einstein that may surprise you

Romantic entanglements, political intrigue—Albert Einstein’s life went beyond scientific genius.

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who revolutionized physics, changing our understanding of the universe. His many groundbreaking discoveries include the special and general theories of relativity and quantum mechanics. But among the general public, he is likely most recognized for developing the equation E=mc2.

Although his professional achievements are well known, they came later in life. Before Einstein became a worldwide phenomenon and lauded scientist, his early life was filled with personal struggles and professional setbacks.

Here are key facts about Albert Einstein’s extraordinary life, including some that may be surprising.

Albert Einstein’s early life and career

Einstein was born on March 14, 1879 in Ulm, Germany. His father, Hermann Einstein, was a salesman and engineer who struggled to get his business ideas off the ground. His mother Pauline stayed home to care for Albert and his younger sister, Maria (also known as “Maja.”)

At a young age, Einstein exhibited unusual intellectual curiosity and wrote his first scientific paper when he was 16. He also had a passion for music. In addition to the piano, Einstein played the violin.

Despite his intellectual abilities, Einstein experienced an early academic setback when he dropped out of a boarding school his parents left him in when they moved to Milan for better employment prospects.

Unable to return to Germany to finish high school, Einstein completed his general education in 1896 at a special school in Switzerland and was accepted to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich.

(Paper towels, solar power—Einstein created many everyday items we use today)

Shortly after graduating, Einstein struggled to find a job but eventually secured a position at the Swiss patent office, with help from a friend. There, he experienced his “miracle year,” when he wrote four of his most famous papers, including his special theory of relativity and the photoelectric effect.

In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” He was 42.

Eventually the rise of the Nazi party pushed him to leave Germany for the United States, where he took a new position at Princeton University, in Princeton, New Jersey, until his death in 1955. According to accounts, Einstein’s final days were seemingly peaceful; he was reading the paper and discussing issues of the day just before he died.

(The tragic story of how Einstein’s brain was stolen)

Romantic relationships

Einstein met his first wife Mileva Marić while he was studying in Zurich. She was a fellow student passionate about math and science. Although she was an aspiring physicist in her own right, she gave up those ambitions when she married Einstein in 1903.

Before they married, Marić gave birth to their daughter while staying with her family in Serbia in 1902. The baby was named Lieserl and historians believe that she either died in infancy, probably of scarlet fever, or was given up for adoption.

In all likelihood, Einstein never saw his daughter in person. Lieserl’s existence wasn’t widely known until 1987, when a collection of Einstein’s letters was made public.

Marić and Einstein had two more children, sons Hans Einstein and Eduard Einstein. Affectionately called “Tete,” Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia and institutionalized for most of his adult life.

(Schizophrenia in women is widely misunderstood—and misdiagnosed)

Like his father, Eduard was fascinated with science, particularly psychoanalysis, and was a big fan of Sigmund Freud, a friend of Einstein. Although they corresponded in letters, Einstein never saw his son again after he immigrated to the U.S. in 1933. Eduard died at the age of 55 in a psychiatric clinic.

As Einstein’s fame grew, he became increasingly busy with professional demands. At the same time, he began an affair with his first cousin, Elsa, the daughter of Einstein’s mother’s sister. They were also second cousins through their fathers.

Anticipating winning a Nobel Prize, Einstein offered all his expected prize money to Marić, so she would agree to grant him a divorce. The award added up to $32,250, which was more than ten times the annual salary of the average professor at the time. Einstein married his wife Elsa in 1919 and raised her two daughters, Ilse and Margot, as his own.

(Who are the Nobel Prize winners? We’ve crunched the numbers.)

Elsa wasn’t Einstein’s only affair. In 1935, Margot introduced him to Margarita Konenkova, and they became lovers. In 1998, Sotheby’s auctioned nine love letters written between 1945 and 1946 from Einstein to Konenkova. According to a book written by a Russian spy master, Konenkova was a Russian agent, though historians have not confirmed this claim.

Political beliefs

From an early age, Albert Einstein loathed nationalism of any kind and considered it preferable to be a “citizen of the world.” When he was 16, he renounced his German citizenship and was officially state-less until he became a Swiss citizen in 1901.

In 1933, the FBI began keeping a dossier on Albert Einstein, shortly before his third trip to the U.S. This file would grow into 1,427 pages of documents focused on Einstein’s lifelong association with pacifist and socialist organizations. J. Edgar Hoover even recommended that Einstein be kept out of America by the Alien Exclusion Act, but he was overruled by the U.S. State Department.

(What is the Alien Enemies Act? Here's how the 1798 law was invoked in the past.)

His political beliefs often put him at odds with Fritz Haber, known as “the father of chemical warfare.” Haber was a German chemist who helped recruit Einstein to Berlin. Although they were close friends, their relationship was often rocky.

Haber was Jewish but converted to Christianity and preached the virtues of assimilation to Einstein before the Nazis came to power. In World War I, he developed a deadly chlorine gas, which was heavier than air and could flow down into the trenches to painfully asphyxiate soldiers by burning through their throats and lungs.

During his lifetime, Einstein was a strong supporter of civil rights and free speech. When W.E.B. Du Bois was indicted in 1951 as an unregistered agent for a foreign power, Einstein volunteered to testify as a character witness on his behalf.

After Du Bois’s lawyer informed the court that Albert Einstein would appear, the judge dismissed the case.